And Jim Walrod Would Know

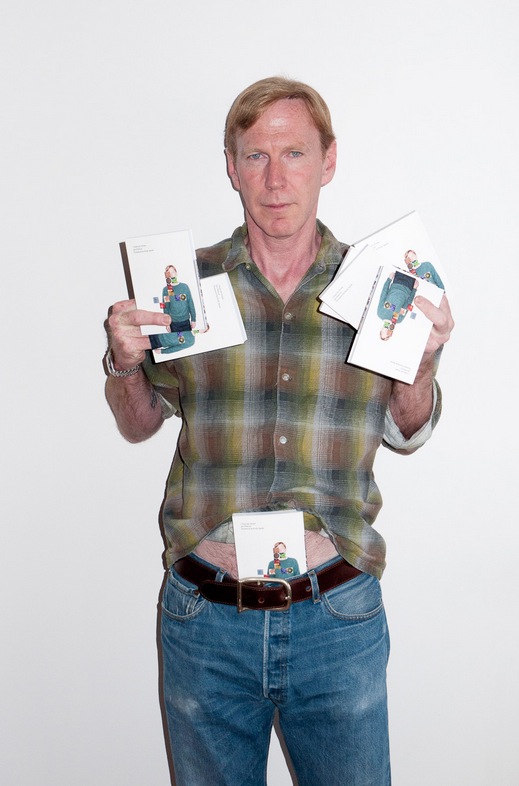

ABOVE: JIM WALROD WITH HIS NEW BOOK. PHOTO COURTESY OF TERRY RICHARDSON

The title of interior designer Jim Walrod’s new book, out now from Powerhouse, is kind of an inside joke. I Knew Jim Knew, with its deliberate use of italics, refers to Walrod’s legendary knowledge of the last century in design and architecture—the phrase is often invoked by Walrod’s friends after Walrod has managed to call up some obscure bit of information.

I Knew Jim Knew is a joyful compendium of this sort of thing: facts, impressions, and trivia—”At the height of his career, Marvin Gaye met with the head coach of the Detroit Lions to discuss his playing for the team,” for example—accompanied by photos both historical and recent, culled from Walrod’s very active Instagram. (The cover features Walrod himself, shot by Terry Richardson, with his face obscured by some of these photos.)

There are scores of people who knew Jim knew—Walrod has an impressive group of friends. We tapped one of them, the artist Will Cotton (the man responsible for, among other things, the art direction of Katy Perry’s “California Gurls” video) to chat with Walrod about the book, Instagram, and the hidden meanings in buildings.

JIM WALROD: Hey man, what’s up? Where are you?

WILL COTTON: Me? I’m in my usual spot. I’m in the studio. In the paint fumes. Hopefully my brain will be functioning well enough.

WALROD: I thought you were away?

COTTON: We were. Just got back late the other night. We did a little trip to Dubrovnik, which turns out to be a very interesting town. It’s got this serious medieval fortification that’s intact and beautiful water and so on. It’s a hell of a place. I enjoyed it.

WALROD: Holy shit. Welcome back.

COTTON: Thanks a lot, man. Well, first of all, Jim, thanks for asking me to do this.

WALROD: Are you kidding?

COTTON: You could have asked pretty much anyone who’s doing anything interesting in New York in the last 30 years, so thanks. I feel like you’ve got such an eye for ferreting out keen design, and that seems to apply to people, too. Most of the interesting people I’ve met, I feel like it’s been through you, and I just wonder if that’s like an organic process for you, or do you just say to yourself, “That’s somebody I need to know,” and then go introduce yourself to them?

WALROD: No, it just seems that there’s a sensibility and a community that—you know, I don’t know if it still exists in New York. I feel like it does, and it expands. But there’s just whole schools of like-minded thinkers and as New York seems to get more and more populated with, you know, finance and banking and less with art and design, you can almost smell them, you know?

COTTON: Who has come onto your radar recently? Who are you spending time with? Anyone you’re interested in in particular these days?

WALROD: Oh, yeah. Jim Drain. Just an amazing, amazing artist. He was actually recommended through Barry McGee, and I always take everything that Barry says seriously.

COTTON: I feel like talking to you about Instagram a little bit if we could; both of us spend some time on there. Especially you. I posted a picture the other day, and it’s an image I’m really excited about, which normally would mean I’m going to make a painting out of it, but I had this thought that maybe that was it—maybe that was the right venue for the piece and that’s all. It seems like it’s been a huge creative outlet for you. Do you feel like those pictures need to have a life outside of those confines? Is that part of how your book came about? Are those Instagram shots in there?

WALROD: Well, yeah, there’s Instagram shots in it, but Instagram is Instagram. It’s really funny that it’s become, like, this forum over the last two years just for communication. And it’s like, I don’t know how many people know it, but you have a show that’s coming up and it’s like if you watched your Instagram page, it’s such a preview of that show and a way for people that won’t see it from around the world. You have a show in London, right?

COTTON: I do. Thank you for mentioning that. That’s how I’ve decided to use it. In the beginning, I thought, “Damn, this could be anything; what am I going to do with this? What do I have to contribute?” For me, the thing I have to offer that’s different from everything else in my life or that might be important to me is what I’m working on, is process, and that’s normally a very private experience for me. My first thought was, well, let me look at what people I like are doing. I looked at your stuff, and the way you use it is very different. It’s not like, “Okay, here is this amazing chair I just saw that I’m going to put somewhere.” The things it seems you post are just the stuff that you see, and I can only guess that has some relationship to the stuff you do more so-called “professionally.” Or is it just a totally separate piece of your brain that’s working there?

WALROD: I think it’s a little bit of both, in a weird way. It’s just a dialogue during the course of the day. Basically what I use it for is to document what I walk past, see, or just want to put out there. It’s funny: There are so many people that are willing to put up design stuff on Instagram, and are so proud of their homes. I just couldn’t even imagine putting up anything that I’d worked on.

COTTON: Yeah, yeah.

WALROD: It just doesn’t seem like a forum for it; where for somebody like you, it’s such a glimpse into the studio. For what I do, it’s like, okay, there’s interior design, but there’s a language between design, the city, and the places that we live. And that’s what I usually try to document through Instagram, whether it be the good, the bad or the ugly of it.

COTTON: Very much so. When I look at that, it’s eye-opening. We walk around the same streets, and we see the same stuff, and I do not see that stuff that you’re seeing until I see it on your Instagram page. And, you know, same thing with furniture. Three years ago, when Rose and I got this loft and were about to renovate it, I went to you for advice, and you handed me a book—Joan Kron and Suzy Slesin’s High-Tech, which was great—and then three movie recommendations. Do you remember what the movies were?

WALROD: Probably An Unmarried Woman would have been one.

COTTON: Yeah, there’s a great loft scene in there.

WALROD: The American Friend?

COTTON: Yep. And I think the third might have been The Eyes of Laura Mars.

WALROD: There it is, the New York trilogy.

COTTON: I loved having those points of reference. That made so much more sense to me than just like, well, you know, go to such-and-such store and buy this piece. You’ve designed things as far-flung as an airplane interior…

WALROD: I’ve done a few jets by now, yeah.

COTTON: You’ve done a few jets. [laughs] Would you do a spaceship?

WALROD: You know, it’s funny. I got to see the space plane. I’ve been working with Gulf Stream and also just kind of poking my nose in the technology around jet design, which is mind-boggling to me, because I barely have a high-school education. Any time I ever tell anybody I’m working on jets, they look at me like, Hmm, is he lying? [laughs]

COTTON: I’ve always been interested in NASA design, but really because it’s this kind of pure functionality design. The Mercury program through the Apollo program through the space station that’s up there now; it is designed, but I think it must, in some ways, just be de facto, “This is the most necessary thing,” as opposed to, “Oh, wouldn’t this window look better if it were oval than square.”

WALROD: It’s ironic, too, because one of the movies that’s constantly referenced in design is 2001: A Space Odyssey, and there’s only four real pieces of design in the movie. There’s a Djinn chair by Olivier Mourgue. There’s some Arne-Jacobsen silverware, there’s a George Nelson desk, and that’s about it. Stanley Kubrick was able to get a point across with four pieces of design. For years, any time I did anything that was remotely ’60s or ’70s, people would be like, “It’s so 2001.” And I’d be like, “Well, if I only used four pieces of design…” [both laugh] And that, I mean, that’s like really stripping it down. That’s like Miles Davis only playing four notes, you know?

COTTON: You’re particularly well-known for your encyclopedic knowledge of 20th-century design. Have you ever done a project that’s strictly 21st-century?

WALROD: Yeah, I have to design with stuff. Actually, Mike Diamond, from the Beastie Boys—his mother traded in a collection of some of the best modern paintings, everything from [Piet Mondrian’s] Broadway Boogie Woogie to Picasso’s Bathers. She wound up collecting Old Masters, and at that time she had all Marie Antoinette’s sitting room furniture in the apartment, and she probably had just turned 80, and her mandate was that she didn’t want to see anything she had ever seen before.

COTTON: Wow.

WALROD: So we went on a tear of looking at things—she basically said, “I don’t want anything in this house that’s older than six months.” So with the backdrop of these incredible Old Masters and Berninis, I got to explore contemporary furniture in a way that I never had before. It took an 80-year-old woman to aggressively push me in that direction.

COTTON: And what’s your verdict? Were you able to find great stuff that’s happening now?

WALROD: It was really great. At one point, looking at a chair and I asked how long the delivery date was, and the guy said 14 weeks. She said, “14 weeks? I don’t know if I have three months.” [both laugh]

COTTON: That’s terrible. She’s still going strong, though, isn’t she?

WALROD: Yeah, she sure is. Yeah.

COTTON: I heard a rumor you’re working on a forum that would make design more visible and more accessible to some of us.

WALROD: I actually want to do a design show—a public show, next year, around the time of Frieze.

COTTON: Oh, fantastic. And that would be like young, living designers showing their work? That sort of thing?

WALROD: Yeah, yeah. Young, living designers, and contemporary companies, too. The Italian companies, which most people don’t get to see. It just seems that design never gets into the hands of people that like design, you know? Or want design, or should have design. It always just sort of funnels down and goes to the rich or someone who can afford a decorator, and, you know, it’s not really as democratic as it should be, and I hope I can do something about it.

COTTON: I love the idea. Let’s see. Last time I ran into you on Orchard Street, you were headed to New Jersey for some kind of field trip. I’m curious where you were going. [both laugh] Did you have a destination in mind?

WALROD: Yeah, probably Newark, which has probably become Williamsburg West, to some degree. Good food and, you know, Portuguese people everywhere. Yeah, most of the time when I’m leaving New York it’s just because I can’t take New York anymore, even though I love it as much as I do. [laughs]

COTTON: What’s the largest pancake you’ve ever eaten?

WALROD: [pauses] That would be the Newport Pancake House in Jersey. That’s the place.

COTTON: That’s right. I remember that. Because you took us out there one time, on one of my few field trips to New Jersey. That was a hell of a big pancake.

My take-away from the book is really how history gets written on these pieces of architecture. Granted, it’s mostly in the minds of the people who have been around to see it, but there’s something really palpable about that. When you walk around New York now, you know all these points of reference: “Oh, that’s where John and Yoko lived.” It makes a place have meaning, because something’s happened there.

WALROD: For some people it is, I think other people are oblivious to it. I was walking down the street one time and I turned up the Bowery, and, there’s a bar next door to where Robert Frank lives, and there’s a bunch of yuppies standing outside smoking cigarettes and making noise, and Robert Frank was yelling at them. [Cotton laughs] Robert fucking Frank was standing there and screaming at these people and they were like, annoyed. I was just thinking to myself, if I could get Robert Frank to yell at me, talk to me, stand there, look at me, it would make my fucking year. And they’re just completely oblivious and think this is just some crazy old man who lives in a dump off Bowery, that’s probably a pain in the ass to the people who own the bar. So there’s points of references throughout New York that aren’t there for other people. That’s the thing I wanted to show in the book, was documenting these stories that were mine, and other people’s stories, and how they are passed on.

Book culture has also become something that’s kind of incredible to younger people now, because of the Internet. If you go to any of the book fairs—PS1 or the MOCA Book Fair—none of the people are over the age of 40 years old there, and they trade and buy books, because they’re almost antiquities at this point. They’re not really important, in a way, because the Internet is how information is taken in.

COTTON: So you’re saying there is a group for whom those things are becoming fetishized objects?

WALROD: Oh, yeah, the generation that’s been blocked out of buying art. It’s become probably the most interesting sub-culture to me, besides Instagram and these anonymous ways that people communicate between each other. And that was the point that I was trying to get across with the book, is that there’s a generation of people that do fetishize books and do fetishize catalogues and do look at them as something important. The same thing with magazine culture: because magazines don’t make the amount of money that they used to, it’s become important again to another generation of people to actually read them. And it’s very, very pinpointed to the select people that actually fetishize and go in and look at them.

COTTON: I wanted to ask you about Malcolm McLaren, a guy you introduced me to—he, as we know, loved to tell stories, but also give advice. Is there any advice he gave you that’s really stayed with you?

WALROD: It’s funny—everything that Malcolm did predated everything that’s happened in culture in the last 25 years. He would always just say, “Be generous with your references, but be frugal with your money.” [both laugh]

COTTON: I love that. Do you have any particular advice for a young designer just starting out?

WALROD: Yeah: don’t look at magazines. I always look at magazines and wind up standing there like, “Okay, well, whose house looks like this? Who lives this way?” I never can really quite understand what the point of view is. The only thing you can really do, being a decorator, as far as I’m concerned, is put an educated client towards what it is they don’t know about. The dialogue between a client and a decorator should be more about, “Let me help you get to the point where you can find a comfortable place to live and be exposed to things,” the way that an art consultant exposes a person who wants to buy art to art, instead of inflicting good taste upon them.

COTTON: It seems to me that part of what drives you is an insatiable curiosity, and I think that’s what you pass on to your clients.

WALROD: Lack of taste. [both laugh]

COTTON: I wouldn’t call it anti-taste, but it’s something that exists outside of taste.

WALROD: Yeah, what does my taste have to do with the personality of the person I’m working for? It’s taking them through a journey of exposing them to stuff, and being able to form a dialogue between the place where they live and themselves. Other than trying to match the curtains to the couch, I don’t know how to do that. If somebody asked me to design a really beautiful room, I don’t know how to do that.

I KNEW JIM KNEW IS AVAILABLE NOW FROM POWERHOUSE BOOKS.

WILL COTTON IS A NEW YORK-BASED ARTIST. HIS NEXT SOLO EXHIBITION WILL OPEN AT RONCHINI GALLERY IN LONDON THIS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 25.