U Before Me

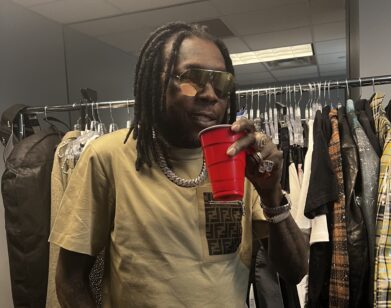

ABOVE: J.C. HALLMAN. PHOTO COURTESY OF CATHERINE MICHELE ADAMS.

In 2013, we spoke with author Nicholson Baker about his 10th novel, The Traveling Sprinkler. In 2015, we interviewed J.C. Hallman about his book of creative criticism, B & Me (Simon & Schuster). Calling the book creative criticism, though, doesn’t do justice to the B and Me‘s inventive narrative. B & Me is a love story and a look into the writings of Nicholson Baker, but also, as the book jacket plainly states, “a true story of literary arousal.”

We met with Hallman at the Green Line in West Philly, a coffee shop frequented by Hallman when he taught at the University of Pennsylvania. When we arrived, Hallman was sitting in the back next to two men playing chess. After moving to a table at the front of the coffee shop, we sank into a conversation about break ups, love stories, and David Foster Wallace.

JARED LEVY: I got your book in the midst of a break up. I began reading, and I thought to myself, “Is this going to go poorly? This relationship between the author and his girlfriend?” I inserted myself in the narrative, as I think many readers do. Is there anything specifical that you want your readers to experience with this book?

J.C. HALLMAN: Something that I’m pleased with about the book—if it’s okay to say that you’re pleased with your own book—is that there is a wide range of emotions. At some points I hope it’s witty and funny, other moments I hope it’s troubling and sad. I think that there’re moments where people thrill with recognition and also moments where you find yourself fervently disagreeing with me.

The basic controlling metaphor of the book is this idea that reading is arousal. What I hope happens is that people recognize that is the case. That means a lot of different things. Even outrage is a form of arousal and what our reading lives should do is kick us out of the torpor of daily routine life and make us experience emotions we otherwise easily avoid.

I really took to an idea that I sensed running through Baker’s work, which is simply that people often have a hard time saying the truth, or listening to the truth. It’s probably related to Gertrude Stein, saying something about how masterpieces are necessary, but not always welcome. I wanted to say true things that I felt were true, without respect to whether I would leave the reader entertained or comfortable.

How does that translate to the reader experience? I hope that they register, if I’ve managed to achieve something of truth, regardless of how it makes them feel in a given moment. Reading is about those things, which need to be said which we cannot utter or discuss in any other precinct of human discourse, as I say in the book.

We can be brazen, outrageous, or explicit in books when in our regular lives we are not. That’s exactly what books should do. That’s supported by the range of things that Baker has taken on, whether it’s writing a book that tests the integrity of the first amendment by threatening to kill a president, or whether it’s flirting with something that’s pornography, that toys with ideas of the taboo or the obscene.

LEVY: Do you think it’s necessary to have read Nicholson Baker to read your book?

HALLMAN: I don’t think so. Baker is the ostensive subject of the book. I tend to think that what all books should do is figure out how to transcend their ostensible subject matter, to recognize that whatever subject matter they choose becomes a vehicle to some higher set of ideas of which the ostensible subject is only a representative example.

Baker’s a really interesting writer, because many people read him yet he’s very far from being a household name. Even the writers who have achieved a great deal of fame by emulating him—Junot Diaz and David Foster Wallace—they’re far better known and yet there’s this guy in the background who seems to be playing this important role in the literary world, however unheralded he might be, and so to that he becomes the idea of a writer.

LEVY: One of the things I love about Baker’s books is that I find myself reading his narratives, but then, through his writing, I learn new things that spin me in new intellectual directions. In the Traveling Sprinkler, Baker writes about Quakerism and it made me want to learn more about Quakerism. In the same way, what I liked about your book was that I learned new ideas that spun me off in different directions. I got a copy of Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse. I was curious when you mentioned it in your book. How do you react to that idea that your work opens up intellectual avenues for the reader? How do you react to the broad idea of literature interacting with the reader’s life and pushing them in different directions?

HALLMAN: I think you’re tapping into something that was important to the basic premise of the book. Part of the crisis that the book chronicles—my own crisis as a reader and thinker—is the sense that somehow I’d been reading wrong for a long time and that I had been thinking of reading the canon.

I questioned, “What are the great books?” If there was a writer that I’ve heard of, I wondered, “Well what are one or two books that I can read, so that I feel like I’ve got them, so that I can move on to the next person I’m supposed to read.” That’s a really prevalent view and if you teach for any length of time and go to department meetings realize that’s the name of the game, mostly, though not everywhere.

Not everyone likes this practice. There’s a lot of resistance against this idea. Nobody knows quite what to do about this, so setting out to write a book about one author—ostensibly one author—was a way to break that mold and what it did was it let me return to a much more organic process of following ideas or authors.

In reading Baker, I did what you’re doing, reading a number of the books that Baker mentioned throughout his works.

LEVY: You shared your book with Baker. Do you know if he’s read it yet?

HALLMAN: He was told of the book when it was in proposal. I wasn’t told of this until much later. He signed off on it and said, “Yes, let him go ahead and do it.”

When we had a solid first draft, I actually gave him an option. I had 20 questions from his life; it gets pretty intimate. I was making some inferences from interviews and feature stories or taking things from feature writers that quoted him. I said, “I could send you this list of questions or I can send you the book.” He said, “Send me the book.”

He wrote back 10 days later and said that he had been dreading reading the book for a year since he had heard about the project. But then, after reading the book, he said he didn’t have to dread reading it, because it was funny and kind. I don’t think I should put too many words in his mouth, but it was the kind of email that you wish you could have tattooed on your stomach. It was really wonderful and really gratifying to hear that he had recognized the value of the exercise.

LEVY: Where does this leave you? Do you need to pull back and write fiction? Or has this sparked your interest to continue in the path of creative criticism?

HALLMAN: Uh, well, no. I know I’m not going to do that, if for no other reason than, like Baker, I worry about writers finding a groove and coasting.

I sold my next book, which is a kind of bizarre story set in the country Swaziland. It’s a nonfiction book. It’s about a serial killer in Swaziland. I’m still in the process of figuring out how to tell the story, but it’s using this little tiny country in sub-Saharan Africa as a microcosm, a symbol of I don’t know what yet. I’m still researching. Even the extent to which I am going to be included in the story isn’t clear to me so I’m still in the development stage. In part it’s a response. I wanted to turn a radical corner.

Katie Roiphe said of Baker and [Geoff] Dyer that Dyer is a writer who never stays home and Baker is a writer who never leaves home. That’s insightful and generally true, but not entirely true. For myself, I want to have as varied a career as I can. From a publishing perspective, that’s not always a good idea, because the trend in publishing is finding a subject and sticking with it. But I find myself admiring the writers who earn the right to move from subject to subject. Baker is one. Dyer is another. Rebecca Solnit is another.

What compels me as a thinker, what fires me up about a book is that it’s something totally new to me. Swaziland is an idea that’s been in the back of my head for many years and I’m finally getting a chance to do it. That’s what’s coming next.

B & ME IS OUT NOW.