RETROSPECTIVE

“If You Can Walk, You Can Dance”: Inside the Whitney Museum’s Alvin Ailey Retrospective

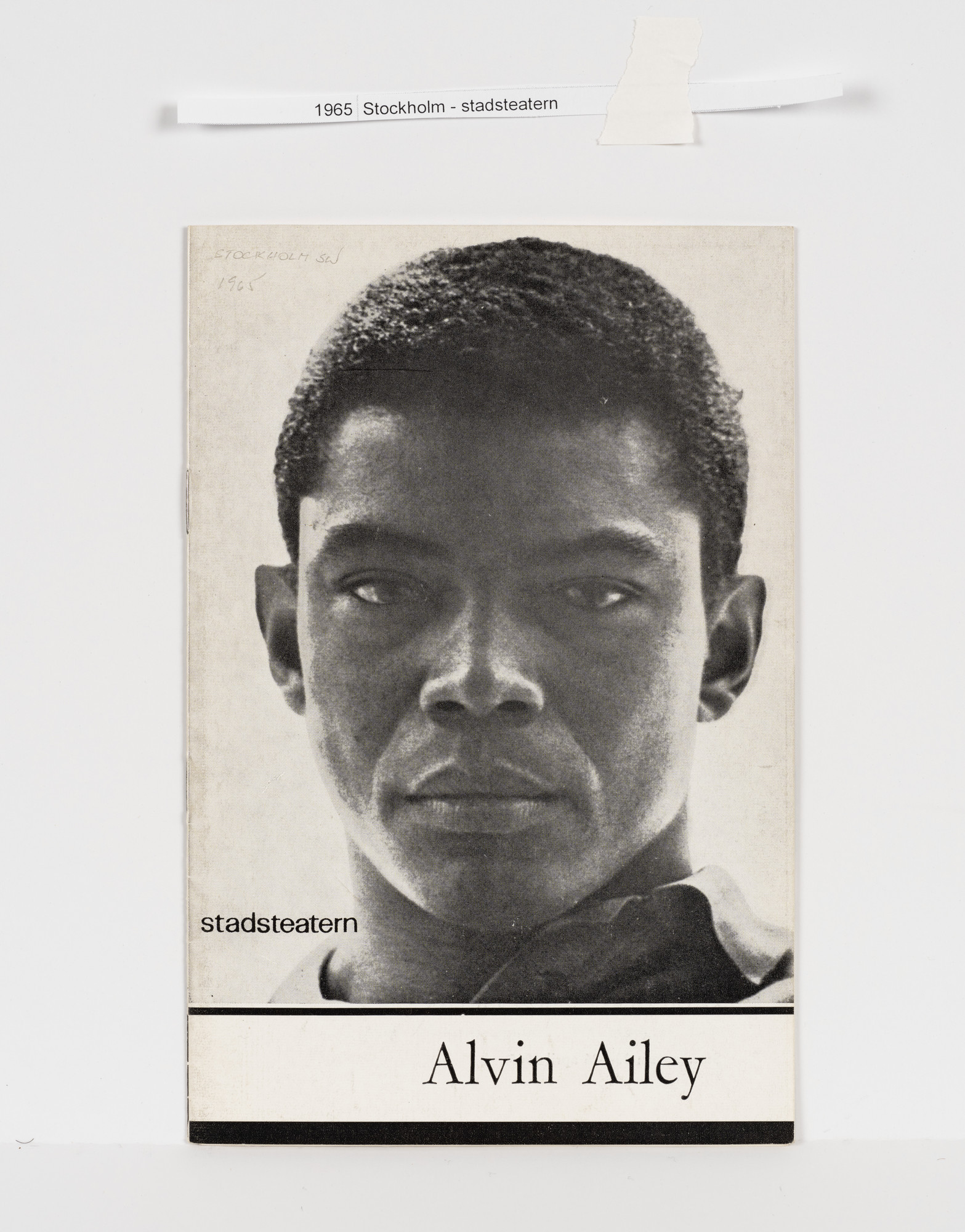

Alvin Ailey. Photo by John Lindquist. © Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In 1949, as legend has it, Alvin Ailey, then a young gymnast, followed school buddy and fellow future dance icon Carmen de Lavallade to the famed Lester Horton “Dance Theater” on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. It was a simple gesture that would lay the groundwork for the future of American concert dance. After Horton’s unexpected death, Ailey took over the Horton company for a while before starting the eponymous Alvin Ailey Company in New York, forming a beautiful, long and deeply intersectional lineage that incorporated dance, art, and innumerable interconnected histories culminating in the very first exhibit of the archival record of the Alvin Ailey Company, a show five years in the making and currently on view at The Whitney Museum of American Art.

I started my career in art as a dancer, studying the craft in college. Walking through the show earlier this month, I fought back tears; the footprint this company had on the world is indescribable. Watching the 17-screen installment of the Ailey Dance video archives, I’d never even considered how much of my own training was rooted in the Ailey tradition and technique. Ailey is not just Afro-American dance language; it is the American dance language, full stop. The show, curated by Adrienne Edwards, carried a somber tone, as it was foregrounded by the death of Judith Jamison, Ailey’s muse and the woman who’d become the main artistic director for the company following Ailey’s death in 1989. But still, the exhibition felt joyous and celebratory. A few days after my visit to the Whitney, I got on a Zoom call with three of Ailey’s most acclaimed pupils—Masazumi Chaya, Donna Wood Sanders, and Sylvia Waters—to reflect on Ailey and Jamison’s titanic legacies.—BRONTEZ PURNELL

———

SYLVIA WATERS: Hi, Brontez.

BRONTEZ PURNELL: Hello. How are you?

MASAZUMI CHAYA: Can you see me?

PURNELL: I can see everyone.

CHAYA: Nice meeting you.

PURNELL: Nice meeting you, too. Good afternoon, I guess. It’s well past morning, but if I could, I would just like to really get into it. I know that this [retrospective] was kind of the first thing that happened after Judith Jamison’s death. I’m sure that was a very hard thing to deal with. How did y’all approach this knowing that there was such a deep, heavy, and influential loss at the start of this process?

WATERS: I think the first thing we were all preoccupied with was how to celebrate her. I mean, the season was happening, Edges of Ailey and all the things that have to do with opening night, and the special guest who was being celebrated, Jodie Arnold. So this was a big, big, big—I don’t want to say “task,” but calling to properly celebrate her, because our hearts were very heavy. It’s still unbelievable for us. So how do we put one foot in front of the other and share Judith’s legacy with the world? It’s still difficult.

PURNELL: Walking through the show, it felt heavy, but it was really so beautiful.

WATERS: Well, she was so beautiful. That’s what came through. I think it came through all of us.

PURNELL: Oh, yeah.

DONNA WOOD SANDERS: I also would like to say that we all knew how fantastic and wonderful Judy was and worked with her personally and as a friend, but the effect that she had all over the world—it’s hard to encompass how it was so universal. She touched so many lives, as was evident by the number of people [at her memorial], and the generations from Judy’s down to the children of the [Alvin Ailey] school. You just saw one generation after another during the ceremony. It was beautiful.

CHAYA: Yes. Judy was my mother. [Laughs] We did a dance called “According to Eve.” She played Eve, and I was one of her sons. Since then, she always joked around in that way. So that day was very difficult, but at the same time, I saw in her face some kind of peace, so she was ready. She left so much love for us to continue working on, for dancers, or for upcoming young artists, painters, choreographers, musicians, anybody.

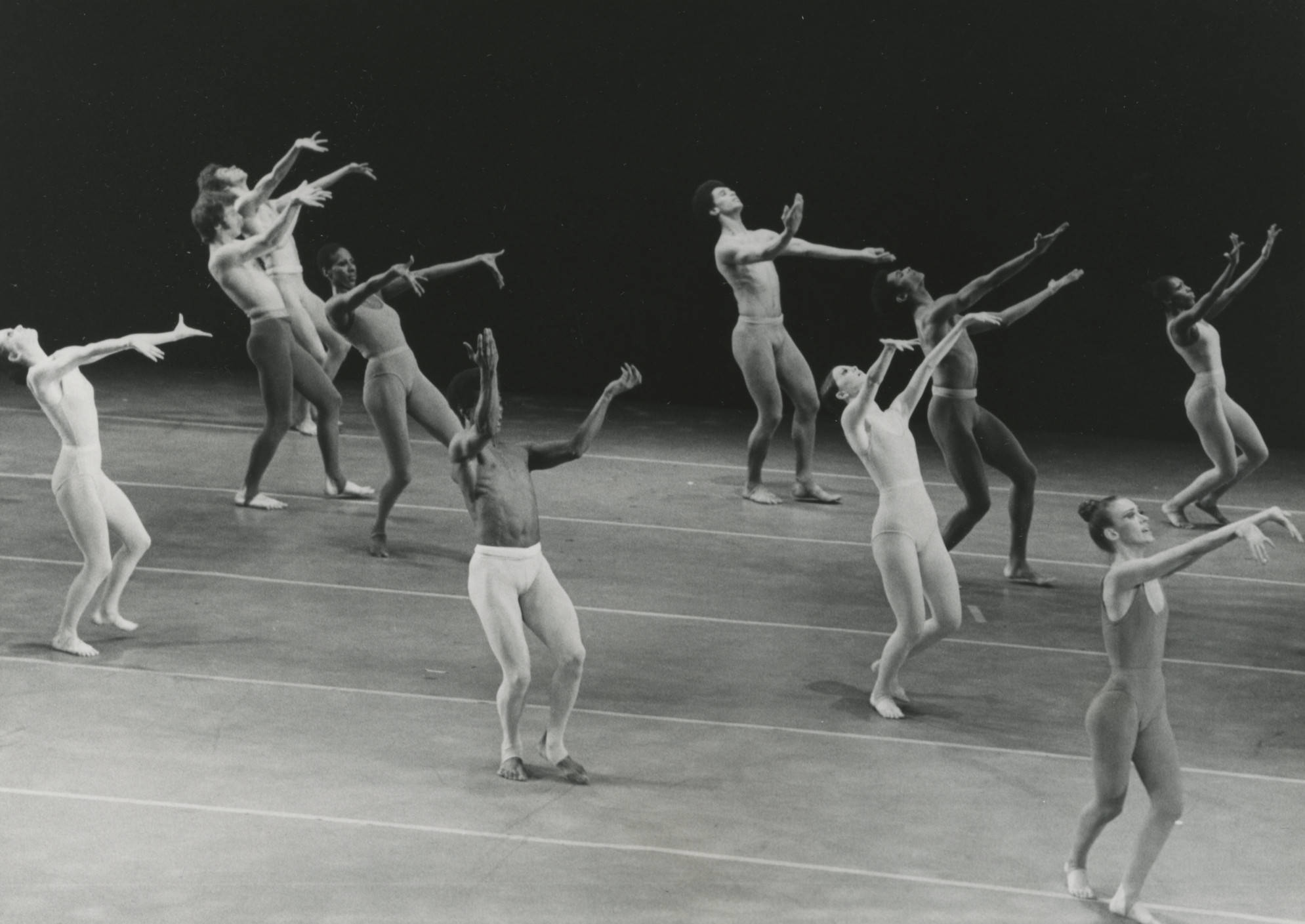

Fred Fehl, Judith Jamison, Clive Thompson, and other dancers in Streams, ca. 1970. Photograph, 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.78 cm). Fred Fehl Dance Collection. Courtesy Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. © The Harry Ransom Center.

WATERS: Alvin used to always say, when something spectacular happened, “Well, I guess you’ve moved on up to a higher calling.” And I think of that with Judy, because this was her calling. Her life was so dedicated to Alvin Ailey’s legacy and to keeping her “garden,” as she called it, watered and filled with all of this wonderful art. So as difficult as it is for me to still believe and accept that she’s not here, it’s definitely a higher calling. I mean, Judy wasn’t a cheap date. She loved beauty and she had exquisite taste, and she wasn’t afraid to say “no” if you gave her a gift that wasn’t really for her. She wasn’t afraid to say, “I can’t use this. You keep this.” I mean, her exquisite-ness was so refined.

PURNELL: Do y’all remember some of the first meetings you had with Judith or Alvin, kind of how y’all came into the fold?

WATERS: I certainly do. I talk about it all the time. I have two stories. I’ll make them brief, but when I first met Alvin, I was about 14 years old, and actually it was a sighting, on East 57th Street between Lexington and Park. My girlfriend and I were just kind of roaming around exploring the city and this gentleman approached, extremely handsome, and he had on a pea coat and a watch cap. And when we looked at him in passing, he smiled at us and we smiled back and there was nothing lascivious about it at all. We said, “My goodness, who is that?” And we turned around and looked, and he turned around and looked. Well, that really just set us off. It was beyond flirtation. And about two weeks later when I went to my class at the New Dance Group, I was waiting for my class and he said hello. He was my teacher for that day, he was substituting for Charles Blackwell, and that was my first class with Alvin Ailey. Little did I know how this person would be so much a part of my odyssey in dance. And meeting Judith several years later in Paris, she was with the company and I wasn’t with the company yet, and I went by a rehearsal to say hello, because most of the dancers were my friends. There was Judith in the dressing room. And Mary Barnett said, “Oh, Sylvia, have you met Judy?” And she turned around and she had on this wig making her look kind of like Josephine Baker. And she turned to me and she said, “Judith.” And I said, “Oh, hi Judith.” And that was all I had to say. And then two years later when I joined the company, she was coming up 8th Avenue and I was crossing the street. We ran into each other and she said, “Hi,” with the most beautiful, welcoming smile. And since that day, we were great friends, and she was “Judy,” not Judith. I wasn’t scared of her anymore, in other words.

WOOD SANDERS: Well, when I first met Alvin and Judy, it was when I joined the company in September of ’72, and I was very intimidated by everyone there. I was only 17, and I looked up to them all, and I remember when I called Alvin “Mr. Ailey,” they said [to call him] “Alvin.” When I joined the company, I had to learn six ballets in six weeks, and then we were off on the road. And once you get out on the road, it’s like we were one big family, traveling on the same bus and whatever motel we happened to be in at that time. It was a process, but it was a beautiful process. So I not only admired her, I loved her like a sister. And the same for Alvin, actually.

Emma Amos, Judith Jamison as Josephine Baker, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 100 × 32 in. (254 × 81.2 cm). Ryan Lee Gallery. © Emma Amos. Courtesy Ryan Lee Gallery

CHAYA: The first time I met Judy was my audition. She was performing at the Metropolitan Opera House for [Leonard] Bernstein’s Mass, and she was just sitting on the edge of this stage doing a crossword puzzle. Now and then she looked at the dancers, but she kept doing that. Judy kept looking at me, but she didn’t smile or say anything. Then after that, Alvin asked me and my best friend, Oka, to join the company. So since joining the company, we started learning, but I still hadn’t seen Judy. And then somebody said, “Oh, Judy is in Europe.” I said, “Oh, when is she going to come back?” “We don’t know, but she’s going to come back soon.” So she came back and she was married that time, and then she had this ring, and she said, “Oh, I don’t need this ring anymore so you can have it.” So she gave it to me, and I’m still wearing that one old ring. And also, she loved cooking. After rehearsals—Donna, do you remember? We went to her house, the Columbus Avenue apartment. Almost every night we stopped by. I had the best time, actually.

PURNELL: That’s amazing. With this show, I didn’t know quite what to expect because, for instance, with a Martha Graham exhibition, what you’re going to see is a lot of history, but also costumes, ephemera, all centric to just that name. Whereas the Ailey legacy encompasses Horton, Dunham, even some filmmakers. So, how did y’all even begin to edit this show?

WATERS: Well, when Adrienne Edwards had the idea, I met with her early on. We had lunch and we just talked about Alvin, about the company, about Judy, about the school, about everything. I honestly had no idea at that time what Adrienne was envisioning as an exhibit. And working in the archives with the archivist, Dominic Singer, of course, we were there to supply the curators, Adrienne and CJ, with whatever materials they needed: photographs, film footage, interviews, et cetera. But I don’t think I had a vision of how this would all unfold. We were just giving them everything they needed and putting them in touch with people who had all kinds of ephemera, like the journals, which I had given to Alan Gray when Mr. Ailey passed away because I was Mr. Ailey’s executor. When we had meetings, when we had what we called our “contract talks” with Alvin, our yearly evaluations, he always had these notebooks and he would be writing and writing as you’re talking. And I’m thinking, “My goodness, what is he writing?” So when he passed, we found these notebooks and we’re going through them, and I was just terrified turning the page each time, not knowing what I might find. I didn’t want to see my name pop up there. But these notebooks were a very important part of the exhibit, because the journals are sometimes very personal. It just shows Alvin’s thought process. I had no idea what a deep dive Adrienne was going to take into Alvin’s persona. It’s majestic, it’s just huge. And I’m still impressed and blown away by how immersive it is, and how many artists have participated.

CHAYA: One thing I’d like to add is that Adrienne started five years ago. Five years ago, the museum asked her, “What would you like to do?” And then she said, “I’d like to do something about Alvin Ailey.”

Installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Knave Made Manifest, 2024. Photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024.

PURNELL: Wow, so it was a five-year process. I guess it would take that long, huh?

WOOD SANDERS: I would say that Sylvia and Masazumi were very much hands-on with the meetings that took place. They would contact me for any information because I have fortunately held onto all of my papers and photos from when I was in the company. For example, I still have the original tour and casting sheets from when I was in the company, which they really wanted to use. So I sent them to New York and they copied everything. Whenever they would call, I was happy to provide whatever I could scrape up.

WATERS: You were an incredible resource. I mean, we didn’t have cell phones then. We just had those little box cameras, and then some people had real cameras.

WOOD SANDERS: But I have loads of photos from us traveling the world. And I was very happy to provide, even when Mrs. Cooper came to Hawaii with us and sometimes Alvin was hanging out with the dancers, or we could be on the glacier in Alaska or a boat in Hawaii. I just cherished those times, so I kept everything.

Poster of Alvin Ailey YWCA Clark Center performance. Photograph by Jack Mitchell. Courtesy Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institute 2024. All rights reserved.

PURNELL: So there were about 80 performances that went alongside the show. How were the performances curated, and who looked over those?

WATERS: Well, Adrienne worked on this a bit with Robert Battle, who was director at the time, and she had a list of modern dance choreographers that were kind of in Mr. Ailey’s orbit. And then, there are also the components of the Ailey organization. There’s the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which is the first company. There’s Ailey II, which is the second company. There are the students of the school, and there are the extension division students of the school. So all of these components came together to decide what performances would best explain the many aspects of Ailey. When Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane were first coming onto the scene, Alvin said, “Have you seen them?” Because I was not a scout, but I was always trying to present emerging works and emerging choreographers and I’d share that information with Ailey. So he said, “Well, have you seen Bill T? He is at The Joyce.” I said, “Well, I haven’t gotten down there yet, but I certainly intend to.” Well, Alvin was impatient with me and he went and the next thing I knew, Bill T. was at the Ailey School doing a workshop. He did that with several choreographers. Alvin felt, as he so often said, that “dance came from the people. It should be given back to the people.” What makes me so very sad is that Judith never got to see the exhibit. There were a couple of times she was supposed to come and she couldn’t, and I had to deliver her opening night speech, which became my speech for the opening of the exhibit. I was terrified to step into those shoes. She’s such a monumental part of this. But somehow, the curators and all the staff at the Whitney and at Ailey came together in a very harmonious way to have this happen under the curation of Adrienne Edwards and CJ Salapare. It’s been a joy working with them, I’m majorly impressed. And have you seen the catalog?

PURNELL: That thing weighs as much as a baby.

WATERS: Right.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Billie #21, 2002. Dye diffusion transfer print (Polaroid): sheet, 33 3/4 × 22 1/16 in. (85.7 × 56 cm); image, 24 × 20 in. (61 × 50.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Photography Committee © Lyle Ashton Harris

WOOD SANDERS: One thing that I always think about is that I never took into account the historical aspect that we all played in the development of this huge Ailey organization. We were busy just doing. When you’re doing, you’re creating, you’re working with Alvin, you’re working with Judy, you’re working with Talley Beatty, you’re working with all these people. Oh my gosh. We did a whole tribute to Duke Ellington, and you just did Max Roach, Maya Angelou, Sidney Poitier. The names just go on and on, and you didn’t think about how this was all going to impact the future, but it certainly did. It was the gathering of such creative forces and it was quite something. When I joined the company, there were only 18 dancers, and now it’s 32. The studio was in a church, and the studio now has a building, a glass palace of dance. How it’s all evolved is phenomenal and beautiful.

WATERS: It’s been an amazing education. It’s a way of life. We started at 59th Street and there were several moves since that time to where we are now, The Joan Weill Center for Dance. Judy called her the Glass Palace because it was Judy’s initiative that got us to this building. I know Alvin is looking down because he always felt that you can’t have a company if you can’t pay the dancers and if you don’t have a home. He always said that. I have another great quote from him if you want to hear it.

PURNELL: Oh, please.

WATERS: One of my favorites. He said, “What I’m trying to do is to hold up a mirror to society so that people can see how beautiful they are.”

PURNELL: I have been really moved this whole time, so I’m trying to keep it together, but very, very badly.

Lorna Simpson, Momentum, 2011. 2-channel video installation, color, sound, looped, 6:56 min. Courtesy of the artist. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

CHAYA: Judy also loved to teach students. After she gave that directorship to Robert, she often had a little special class for the students, because she knew the company would have to train kids to survive. I would run into her like, “What are you doing?” And she said, “Oh, I have to teach a class.” Oh my god. We have to continue to do that, to educate students and young people.

WATERS: Yes.

PURNELL: I go to New York every year, but I have still yet to take a class at Ailey.

WATERS: Well, you better get yourself over here. If you can walk, you can dance.

PURNELL: Dance was my first major, actually. I got my BA in dance and then my MFA in art from Berkeley.

WATERS: Oh, fantastic.

PURNELL: Next year, I’m doing Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring at Performance Space New York, if y’all want to come by.

WATERS: Oh, please!

CHAYA: Yes, please!

PURNELL: It’s going to be very black and very angry.

WATERS: Black and angry, okay.

PURNELL: And I just wanted to thank y’all for your time. It was an amazing show, and it’s a wonderful legacy. I was very, very, very inspired by Ailey as a young dance student here in the Bay.

WATERS: Well, thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

WOOD SANDERS: Happy holidays.