DANCE

“It’s an Infinite Dance”: Inside Choreographer Ralph Lemon’s MoMA PS1 Retrospective

Ahead of his major solo retrospective Ceremonies Out of the Air at MoMA PS1, polymathic choreographer and visual artist Ralph Lemon is thinking about freedom: what it is, what it isn’t, and how he’s found it over the course of his four-decade-long career. “Freedom doesn’t exist without some container,” he told me over Zoom on a Friday morning in early October. “So it’s like, how do I find the container to be free?” For this occasion, Lemon’s “container” is PS1’s Queens campus, which will host both the exhibition and a series of performances featuring artists Okwui Okpokwasili and Kevin Beasley. In our conversation, Lemon reflected on how his collaborators have shaped his practice, re-performing old dances, and the “generative working tension” he’s found in museums.

———

MADELEINE SEIDEL: I’m just looking at my notes here because it’s early in the morning. I can get flustered.

RALPH LEMON: Likewise. I’m not sure how coherent I’ll be.

SEIDEL: We’ll have a great time. So, the title of the exhibition is Ceremonies Out of the Air, and this is taken from a lecture performance series that you’ve done a few different times, particularly around 2015, 2016. Why did you choose this title for the exhibition?

LEMON: I just love the phrase. It feels simple and poetic, and it also feels like that’s what I’m sharing with an audience. The sense I get when I’m sharing my practice—not that these are ceremonies, but that it’s a nice container for the whole exhibit. The actual phrase comes from Cormac McCarthy, so it’s a borrowed phrase that feels beyond my own language.

SEIDEL: You’ve had a long history with MoMA, particularly working with one of the exhibition’s curators, Thomas J. Lax. What were the conversations that led you to this really major solo exhibition in New York, which is your first in around a decade or so?

LEMON: Well, my work has a rhythm, and there are different parts to the practice. I have a part that’s about performance that happens at certain times in my life, and parts that are about writing, and parts that are about making visual marks. This show is interesting because Connie Butler, after she became director [at MoMA PS1], called and said, “I’d like you to do something here.” I know Connie; she’s a friend and we have a history and a relationship. So, part was me saying yes to the idea of it, but also a large part was me saying yes to Connie because I adore Connie.

SEIDEL: Yes, and you’re always in excellent hands with her.

LEMON: When we began to discuss it, I thought, “Well, this is interesting. It feels like a lot, and it’s not how I usually work.” All these things would happen at the same time, and dealing with the whole constellation simultaneously felt interesting.

SEIDEL: Definitely. When this exhibition was announced, Connie mentioned a quote by PS1 founding director Alanna Heiss about bringing dance into the museum. Do you feel like you’re just bringing dance into the museum, or how are you interpreting that within your exhibition?

LEMON: No, I’m bringing a lot of how I work into the museum. Connie’s very much focused on the performance and dance aspects of my practice, and I’m thinking very much about the whole. There’s an interconnectivity to it all, but it’s much, much more than dance.

SEIDEL: Right. It takes different collaborators to pull different aspects of your practice out. One of the major parts of this exhibition is going to be your ongoing project series, Rant (2019–), and all of its different iterations within the museum. So you have the version that’s going to be a video installation, and then there’ll also be performances of Rant #6, which you say is maybe your last Rant.

LEMON: Maybe. Part of me hopes so. It’s a lot. I guess I’ve been saying this for 30, 40 years. I think when you find yourself confronting these enormous questions, it’s daunting and you have no choice but to dance with the question. And it’s an infinite dance, I’m discovering.

SEIDEL: The installation version of Rant was up for just a few days at The Walker [Art Center] in Minneapolis, another fantastic institution that you have a long history with. How has it been revisiting this, especially in such a different context from the live performance it was initially done in?

LEMON: Well, it’s a very alive, compelling, urgent thing. So when I talk about the final version of Rant, it’s not like it can really go anywhere. It can’t be diffused, or dissipate. Either we leave it and let it go somewhere else, or we keep having this conversation with it. It is, in part, a conversation with Kevin Beasley, Okwui Okpokwasili, Samita Sinha, Darrell Jones, Paul Hamilton, Mariama Noguera-Devers, Angie Pittman, (Lysis) Ley, Dwayne Brown and myself, as human beings and as artists. Our blackness is a big part of the conversation too, and this idea of sound and movement. We’ve expanded the conversation into Rant, and then Rant helps us continue how we talk to each other.

SEIDEL: This piece has had so many different lives. The one I’m really thinking about is Rant #3 from 2020. It felt like such a collaborative piece–it’s this overlay of the dancers and you’re taking all of these quotations from different writers and thinkers, even pop culture figures that loom large in your work. So how do you approach that collaboration, both with live and more historical collaborators?

LEMON: That’s a good question. With the collaborators, we’re making it clear that there’s a more cogent agreement being made. Everyone understands within their particular physical, expressive, creative point of view what the locus of this thing is. And I’m not sure I could describe what that locus is, but I think there’s an agreement around how everyone can live with it and be with it. With the text, I am appropriating these other voices and bringing them into the fray. Their writing is part of what we’re all dancing and wailing about.

SEIDEL: It’s almost like you’re evoking these different people and bringing them to the group.

LEMON: Or they’re helping to inspire or initiate this thing we’re trying to make manifest. And I’m doing it without their permission. Although I did ask Fred Moten to give me his most punk piece of writing, so that became the Moten text (something from Stolen Life, pp. 253-54.) in that particular Rant. It’s intense.

SEIDEL: Absolutely. The Rant works, even though they’re very prescient, feel tied to a time and place. And that’s something that I see in your work a lot, especially with your Geography series where you’re going to all these different locations and letting that inform your practice. What drew you to essentially adopting locales and cities as co-conspirators in your work?

LEMON: I think it was accidental. It was my survival, and trying to make sense of not having a more traditional dance company anymore, which was a lot about family to me. It was very much a familial conversation about creatively making a dance or choreographing. Then the family started to come apart, just in the sense that dancers left and new ones came, and there was a loss of intimacy, an intimacy that was very important in the very beginning.

SEIDEL: Because it’s such a trust-based process.

LEMON: Trust-based, yes. I mean, you fall in love with these people, their dailiness. And it’s organic—people grow up and they leave, and that was not easy for me. The last dance I made in that sense, it disappeared and that was it. So I disbanded the company and I didn’t know what I was going to do. I had interests, of course, but then I had some collaborators, some supporters who said, “You should travel, go to Africa.” Before then I had gone to Haiti and that had changed my life, researching and looking at the African diasporic Black body in a way I didn’t know about. Then I went to West Africa, and that was it. I was like, “Okay, there’s something really interesting about this that has nothing to do with postmodernism.”

SEIDEL: A complete paradigm shift, really.

LEMON: Yeah, I was ensconced in postmodernism or whatever that is or was. I brought that to this other conversation, and I felt that kind of mash-up was super interesting and urgent. A lot of it was about the travel. That became much more interesting to me than actually making things—just being with these other voices and languages and landscapes. The whole Geography Trilogy was a good 9, 10 years of that. The last part, Come home Charley Patton (2005), was about coming home, but then the notion of home became illusory and fantastical. I thought, if I’m coming home, let’s go to a ground zero of Black America as I know it, the American South.

SEIDEL: It’s interesting that you talk about how this period of travel comes from essentially this loss of family and this loss of center. It feels like you traveled to try and find that again.

LEMON: Yeah, but I also knew conceptually that, “I have a family, but I’m going to invent another kind of family.” A different locus about a Black American idea of family. I found that.

SEIDEL: Yeah, definitely with Walter [Carter, a collaborator and subject of many of Lemon’s projects, including How Can You Stay in the House All Day and Not Go Anywhere? (2010)].

LEMON: Yes, Walter Carter and his family in Mississippi. It was perfect. It was real and fiction and speculative, and he was interested in playing, being creative with me from a wildly inscrutable point of view that I could never quite figure out other than that we liked each other’s company. So that was it. And I felt an incredibly generous black hole that I’m still inside of.

SEIDEL: Are any of your pieces of Walter going to be in this exhibition?

LEMON: Yes, there’s a five-chapter narrative on the work with Walter.

SEIDEL: Oh, awesome. That feels like such a shift in your work, that collaboration. There’s almost “before Walter” and “after Walter,” in a way.

LEMON: It’s interesting. I don’t know if I can articulate it in this interview, but in the Rant relationship to Geography and Walter, there’s definitely a narrative of finding more freedom than I’d had before, in being outside of a more traditional idea of an American creative space.

SEIDEL: Do you feel like finding freedom is a major impulse for your work?

LEMON: Yes. And it’s simple because it’s always there. But for me, freedom doesn’t exist without some container. So how do I find the container to be free?

SEIDEL: Exactly. Speaking of containers, I think you’re in a really interesting one right now in terms of the container of MoMA PS1 and the container of the institution. There was a series of letters that was published on MoMA’s website during the pandemic that was presented as this one-sided conversation with you and Thomas, and you were reflecting on your relationship with the institution in terms of your literal exhibition history with it, but also with the racial reckoning that happened in the summer of 2020. There is a part where you say that you, “Look forward to the day when you can be a part of MoMA’s very privileged art world debate again, differently.”

LEMON: [Laughs] You’re very good. You have done your research. I don’t know, maybe you can help answer that after seeing the show. I mean, I went back to the Walker in a real theater just a few weeks ago, and I hadn’t been back in a real theater for almost 20 years. Those spaces add a really interesting kind of poignancy. A poignancy that can be beautiful and felt, but that’s not reliable. Perhaps one has to be more truthful in these alternative spaces where things are less supported, decorated, disguised…

SEIDEL: Right. There’s a lot of freedom, but there are some constraints there.

LEMON: I am finding an argumentative freedom in these more institutional spaces, because there’s a part of me that feels like I don’t belong in these spaces. And in that not belonging, it creates a generative working tension that I feel is useful.

SEIDEL: Yes, and that tension between the place and the work itself adds an entirely new dimension to the work.

LEMON: Right, right. In Geography, I was dealing with those young West African dance bodies— and we’re talking about human beings and not objects—those bodies really didn’t belong on the many stages where we performed that work. But getting back to your question, in the Walker’s theater with this new talent, I was definitely trying to push what that meant from a performative point of view. Now to bring whatever happened there back to the MoMA PS1 Kunsthalle, which is really an alternative space without that kind of theatrical support, it’s going to be a real challenge. And that becomes contentious but also exciting, because it will change what happened at The Walker. I can’t rely on how poignant that piece may have been there.

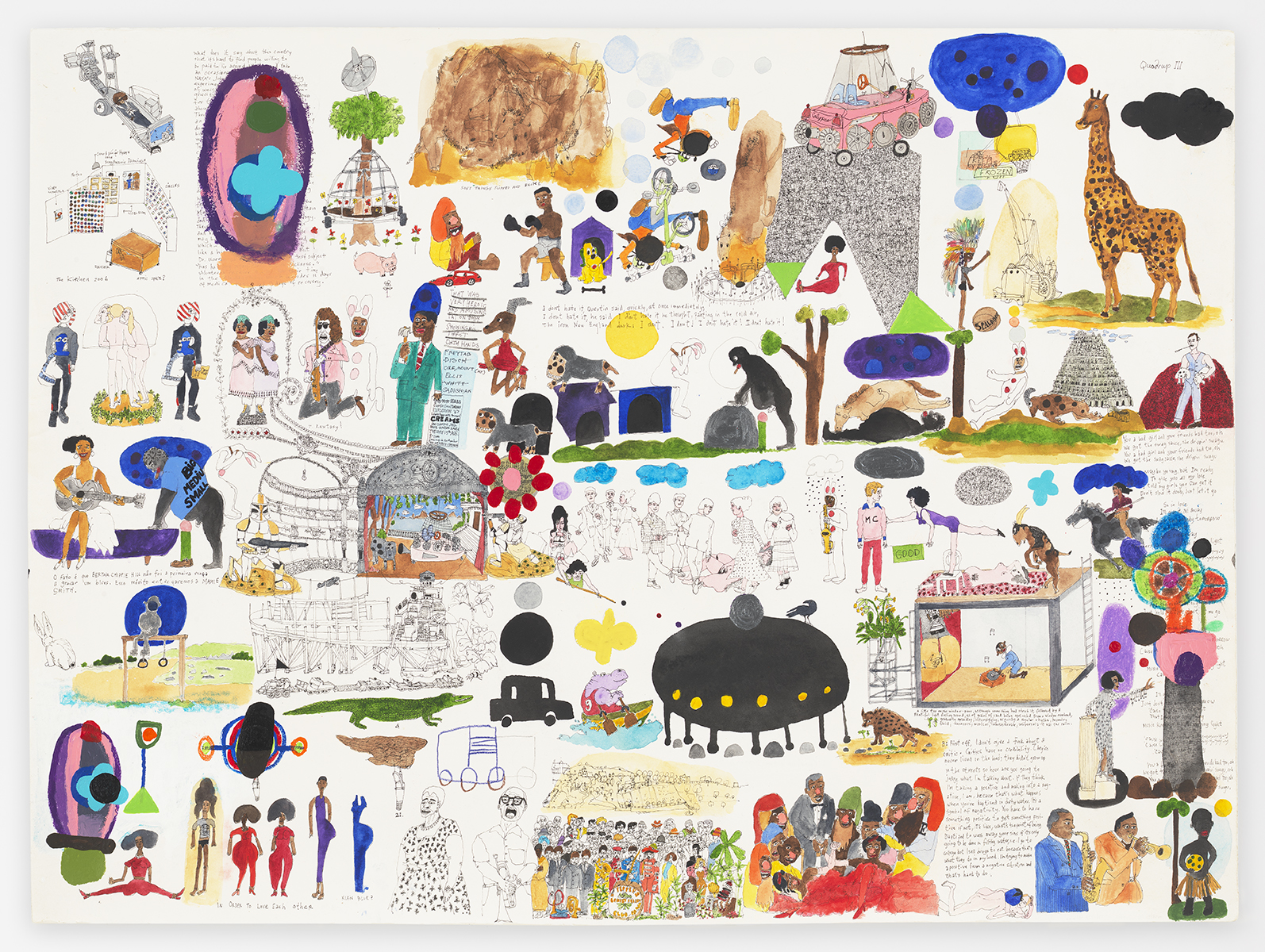

Ralph Lemon. From Untitled (The Greatest [Black] Art History Ever Told). (2015–present). Courtesy the artist.

LEMON: Yes, and in that sense, it stays alive. The interesting thing is that you can really refine the aliveness, and even though you’re working with bodies and performance and the ephemerality of that, you can get to a point where you can repeat these things, and every night the same thing can kind of happen.

SEIDEL: Yeah, you’re trying to harness that little bit of magic found out throughout the course of the process every night.

LEMON: Right. Repetition is not a bad thing, but I think I’ve set up these performative situations where it becomes really difficult.

SEIDEL: Do you see the ongoing performances as almost this live debate as it’s happening in the museum?

LEMON: Yes. And I’m not that rigorous about it from a dialectical art critique .

SEIDEL: Institutional critique is so broad nowadays.

LEMON: I’m not doing any institutional critiquing. I’m critiquing in my own head what’s useful about the performance life of a work. I go to my studio and I draw every day, and I think about these things and they are intimate and private. I don’t think, “Oh, I want to show this in a museum context.” I have my friends like Connie and Thomas asking to share these works to their audience. I don’t know if it’s my audience. My audience are really my friends. It’s really, just about the daily practice of it. It’s very fulfilling and satisfying, but I know this other audience, sharing thing is necessary.

SEIDEL: And I think it’s going to be fascinating to see how your work is staying alive in this context. I think it’s going to be really fruitful.

LEMON: And more important to me, what do I get to bring back to my intimate space from that more public experience? It is like that whole Bachelard argument about the private and the public, and the required tension and argument between those two things, how they’re really different from each other. I’m using that kind of contention as a material, and it’s been useful.

SEIDEL: It’s almost like a medium in itself.

LEMON: Yeah, and dangerous because there’s a lot of energy coming from MoMA PS1. You have a whole institution full of requests. I really just want to be in a studio with my collaborators.

SEIDEL: Well, you have an entirely new set of collaborators now.

LEMON: Yes, now I have a whole building and it’s great. They’re amazing people, and a lot of voices.

SEIDEL: And it seems like there’s going to be even more voices throughout the course of the exhibition once people have their own chance to see it.

LEMON: Yes. Be careful what you say yes to.