NOM

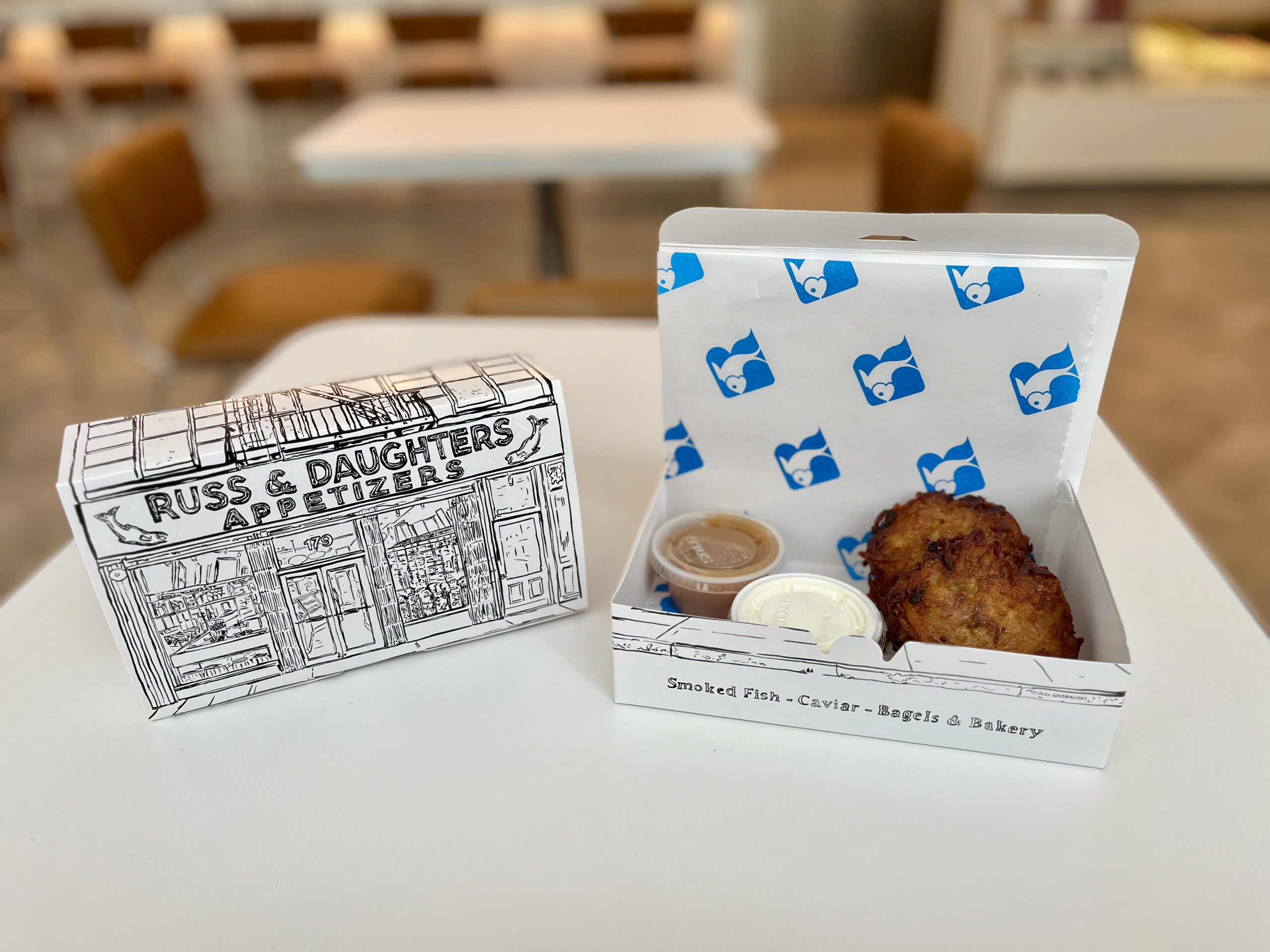

How Josh Tupper and Niki Federman Brought Russ & Daughters to 34th Street

Josh Russ Tupper (left) and Niki Russ Federman (right) of Russ & Daughters. All photos courtesy of Russ & Daughters.

At the elegant, enormous new Russ & Daughters location, a 4,400 square-foot outpost where 34th Street meets 10th Avenue, the eye is immediately drawn to the banquet seating in the back corner, which appears both snug and unexpectedly au courant. Cousins Niki Russ Federman and Josh Russ Tupper, fourth-generation owners of the 109-year-old linchpin of New York breakfast, poured over every last detail of the shop’s new location, especially the seating. They looked at fabric swatches in “sage green,” to match the banquet chairs at the cafe on Orchard Street, and “grayish green,” too. “Early on,” says Tupper, “we went back and forth and back again 100 times.”

He and Federman, whose father managed the downtown shop when she was a child, settled on what they called a “honey brown,” a subtle if still conspicuous update that nicely encapsulates Tupper and Federman’s gentle stewardship of the Russ & Daughters name. The bagels, bialys, smoked fish, and salmon roe remain unchanged, but the new shop has a magnitude and polish befitting of a time-honored institution. “You feel the onus of our legacy and history,” says Federman. Figuring out how to innovate respectfully, she adds, is a “delicate dance.” Shortly after their opening day in midtown, sitting in one of those honey brown booths at the back, Federman and Tupper talked to me about bringing Russ & Daughters to Hudson Yards, how the pandemic inspired the city’s independent restaurants to organize, and Jake Gyllenhaal’s famous tie-die t-shirt.

———

JAKE NEVINS: Hey there, Josh. Thanks for taking the time.

JOSH TUPPER: Of course.

NEVINS: Congratulations on the new Russ & Daughters.

TUPPER: Thank you. We opened last Tuesday.

NEVINS: How are you feeling about that?

TUPPER: Pretty good. It’s going well. It’s been busy. There’s been a few bumps, but I figure they’re not—

NEVINS: Like what?

TUPPER: Some equipment issues, really. With any new place, you test everything, and then you turn it on and start cranking stuff out and something inevitably goes wrong. Nothing we couldn’t handle.

NEVINS: Well, I’m sure it’s nerve-wracking every time. But I’m curious how it feels in this instance. This may be presumptuous of me, but Russ & Daughters is such a name brand, and I suppose that guarantees some baseline measure of success.

TUPPER: We’re extremely nervous about any new opening, of course. You might think that, because we’re Russ & Daughters, it’s like, “Well, it’s going to be fine, it’s going to be successful, it’s going to be busy.” But once we start believing that, I think something’s wrong. Without those nerves, and that anxiety of making everything as good as we can make it, the quality of the product, the design, and the space is on a bad trajectory. So, I was extremely nervous. But maybe the second or third day, I felt my anxiety lower. I was like, “Oh, it’s actually working.” People are actually here, and the whole place didn’t fall apart. The counter people are serving people. Everything is happening.

NEVINS: Right. So, why uptown? Inasmuch as you could say that of 34th Street.

TUPPER: Well, we are always open to conversations, and this started with a text. A friend of mine who works for this development company texted me and my immediate answer was, “No, I’m not even entertaining it.” She texted a little bit, convinced me. I was like, “Yeah, why not? We’ll talk.” Everyone was like, “No, that’s not where Russ & Daughters belongs,” but then we saw this space. It’s really in the cityscape, on 10th Avenue and 34th Street, and the location seemed right. We also want to be able to serve more of Manhattan. The Lower East Side is convenient for a lot of people, but it’s also not that convenient for a lot of people. So it just puts us in a fairly central Manhattan location with deliveries, and orders-to-go, and in-store business. And ultimately we want more and more people to be able to enjoy Russ & Daughters.

NEVINS: [Niki Federman joins]. Hi there, Niki.

NIKI FEDERMAN: Hi. I’m sorry.

NEVINS: I got started with Josh.

FEDERMAN: We’re interchangeable.

TUPPER: Ish.

NEVINS: Niki, how was opening week for you? Have your nerves settled?

FEDERMAN: Well, in addition to all the logistical operations and questions, things like that, there’s always this sort of existential angst, which is probably the reason why I haven’t slept well for the last 12 years. You feel the onus of our legacy and history. And with everything we do, we try to really honor the tradition and keep as much the same, but also obviously innovate. So that’s always the delicate dance that we’re doing. Like, “Okay, how do we preserve what makes it Russ & Daughters, but also move it forward?” So, that’s a lot of the anxiety.

NEVINS: Well, in the course of trying to reconcile tradition and innovation, what sorts of conversations are you two having? What’s something about Russ & Daughters you sought to safeguard, and where did you choose to push the envelope?

TUPPER: That’s a tough one. With every decision we make, in any location, there’s this back-and-forth. You touched on it exactly. The bridge between innovation and the historic significance of the store is something that’s constantly on our mind. So, in design, we started with a black ceiling. And this change is significant, and created quite a few—

FEDERMAN: Headaches.

TUPPER: Design headaches. But we were trying to make this corner spot in this 77-story building that is not at all Russ & Daughters feel like Russ & Daughters. So, we had to take some leaps.

FEDERMAN: And this space, to me, really represents an integration of all of Russ & Daughters. In that way, it feels very holistic, and it kind of connects the dots of what we’ve been doing for almost 20 years. Because there’s the element of the shop, ordering at the counter, then the seating we have at the cafe, the bagel bakery is here, the caviar bar. To be able to put out bagels and bialys all day long is huge.

TUPPER: One of our guiding principles is the Yiddish word “heimish.” Simplicity, accessibility, that’s really what we want.

FEDERMAN: We didn’t know what we were doing. We were learning as we went, designing on the fly. We were counting every penny. We were trying to build and open a restaurant without either of us ever having worked in a restaurant. So it was a very guerilla design-build job. Flash forward to today, we were approached by the developer of Hudson Yards to come here. And that connected with incredible architects and builders and lighting designers. And I think you see that in the end result.

NEVINS: Certainly. It feels a bit more upscale than the Lower East Side location.

FEDERMAN: People are always asking us if they could hold their wedding brunch or their book party or whatever it is at one of our spaces. And if you know restaurants, they’re all totally tiny and cramped. So we wanted to have a space where, at night, everything is movable and it can just clear out and the lighting gets really sexy.

NEVINS: I’d come to a book launch here.

FEDERMAN: Right! Wouldn’t you attend?

NEVINS: For sure.

FEDERMAN: And when we were talking about it with the design team, we had to push back. They were starting to go down the path of making this into an event space. We were like, “No, no, no. We don’t want this to be some sterile event space.” We want people who want to have their event here because it’s Russ & Daughters. We’re not going to deliver some nondescript thing.

NEVINS: What’s the working dynamic like between the two of you?

TUPPER: You answer first.

FEDERMAN: We’ve been on a whole journey together as cousins. We weren’t particularly close growing up, but we did family things together. We have very complimentary weaknesses and strengths. He’s a former engineer, so he’s very good at systems, finance, tech, and I’m more the people person, communicator, human resources, the culture of Russ & Daughters and legal stuff.

TUPPER: We have good strengths that complement each other. I also pride myself on my artistic ability. So there’s certainly crossover.

FEDERMAN: Yeah, it’s not cut and dry. We know each other very well, and it’s nice because, as we’ve grown, we can divide and conquer. I grew up with my parents running Russ & Daughters and vowed that I would never work with my spouse. So in a way, it’s the best of both worlds because we’re family, but we’re not going home with each other at night.

NEVINS: Growing up, was there a moment when you realized what an institution this place is, and what it means to so many New Yorkers?

TUPPER: I’ll start with this one. My mother was not involved in the business at all. I went to school for chemical engineering. I knew Russ & Daughters because we’d come to the city and have lunch, either at Niki’s family’s house or our grandmother’s house in Gramercy. But I had no real inkling until my early twenties when I started questioning what my family’s history was. So it started becoming important to me, but I also wasn’t following her father on Martha Stewart or any of this stuff. So I really didn’t understand the cultural significance until I came to work in the business when I was 26 years old. I started thinking more about our grandmother, who’s the matriarch of our family and really held us all together. And then I heard that Niki’s father was looking for his retirement strategy. And there was, at some point, discussion of selling the business. I wanted the business to stay in the family. I thought it was an important part of society, but I wasn’t understanding Russ & Daughters in New York as an important part of the fabric of the city. I just thought, in general, that these kinds of businesses are important to maintain that experience that gets lost in the big box stores or the strip mall stores.

FEDERMAN: Yeah. Well, for me, it’s different in the sense that I grew up as a shop kid because my parents ran the shop. So I understood in a very on-the-ground way that Russ & Daughters held meaning for a lot of people. I grew up absorbing that. We’d go some places, and sometimes my dad would start talking to people, and if they knew Russ & Daughters, it was like, “Oh my god.” Since we’ve come on board, I think that our presence has given more people more access to Russ & Daughters. Now, it’s really known around the world. I just love that it’s charged with so much meaning. Either it’s like, “This is the food of my childhood,” or it’s like, “Oh, I’m in New York. I read that this is New York food.” One moment where I understood the weight of this was about 2008. We needed to fix the original neon sign from the store on Houston. That neon sign is 60 years old. There was only one neon workshop that would even touch it. Everyone else, they didn’t know what to do with it. It was so old, and they didn’t want to [deal with it]. They couldn’t fix it on site, so it had to come down and go to the workshop. So we were prepared and had a temporary vinyl sign, but it took an hour between the neon coming down and the vinyl going up. And someone was going by in a taxi and saw there was no sign and they assumed that we were closing. Word started getting out, and within a few hours we had people rushing into the store crying, frantic phone calls, people showing up with flowers, like it was a memorial, like someone died. And we had to be like, “No, don’t worry. We’re just fixing the sign.” But it was really powerful because it was pre-Instagram, pre-Twitter. You hear these stories of when a beloved fixture or place closes and people are mourning that. But then to see it happen in real time, you could just feel the way people can’t imagine New York without Russ & Daughters.

NEVINS: Well that’s a good segue into my next question. The pandemic had a pretty dire effect on a lot of the city’s restaurants, new and well-established ones, and I’m curious what lessons you took from it.

FEDERMAN: Well, one thing we learned was that small restaurants like ours, not just in New York but across the whole country, were never unified as an organized force. Everyone just did their own thing. Maybe you did a fun collaboration dinner every once in a while, but that was the extent of seeing ourselves as an industry. Covid obviously exposed the ways in which we needed to band together. So even just in the first few weeks of the pandemic, several restaurants came together and formed what is now a very organized, very effective non-profit called the Independent Restaurant Coalition. I ended up joining five months in, and we collectively went on to get the federal government to create a $28 billion relief fund, specifically for independent restaurants and bars, because we were so adversely impacted by Covid. In a way, it was a very powerful experience, because it also made us feel less alone. Then, I think, a couple things helped us. One is we had the ability to have a historic perspective. Covid was not Russ & Daughters’ first pandemic. It was actually our second pandemic because our great-grandfather went through the Spanish influenza. He opened the store in 1914 and four years later, the Spanish flu hits. He never wrote any account of it or anything, but he made it through. Our grandparents made it through world wars and depressions. So every generation of our family has had some sort of cataclysmic disaster to deal with. In a way, it gave us perspective, because we could look back, but we could also look forward and see beyond the intensity of the moment. So, for example, we did not rush back into reopening the cafe right away, which most restaurants did because they had to. Whereas we said, “You know what? We’re going to just keep this restaurant hibernating, keep doing deliveries out of here until Covid really is over for the most part.” So that took two-and-a-half years. We were lucky, too. Our shop and our shipping business existed for 100 years before Covid. If we just had that restaurant, it would’ve been a totally different story, but we had the infrastructure, so we weren’t scrambling to start shipping out of nowhere. We had been doing it.

TUPPER: We were in a unique position because we weren’t just a restaurant. We had other businesses. We wanted, first of all, to employ as many people as we still could while not having a restaurant. So we started doing takeout and delivery. And it was a sort of online retail shop.

NEVINS: It was very fleet-footed. Is this how Jake Gyllenhaal’s tie-dye t-shirt came about? Was that a pandemic initiative?

FEDERMAN: Oh, total pandemic initiative. Do you have one?

NEVINS: I wish.

FEDERMAN: I wish we had one to give you, but they’re gone.

NEVINS: I figured they might be.

FEDERMAN: Mine got a stain the other day. But anyway, Jake Gyllenhaal is a friend and very devoted Russ & Daughters person. He had a white Russ & Daughters t-shirt that a friend had tie-dyed.

TUPPER: You’re making up stories. My friend had the t-shirt. He was friendly with a stylist. The stylist took it and gave it to Jake Gyllenhaal. And my friend was like, “That’s my t-shirt.”

FEDERMAN: Oh, that’s right. I forgot that part. So periodically, before COVID, he would wear the shirt and then paparazzi would take a picture. And then we would start getting calls from people wanting to buy that shirt. And we’re like, “Oh, no. Sorry, that’s just one-of-a-kind. We don’t sell that shirt.” Then during COVID, he did that headstand challenge, where Jake was on his hands trying to take off his shirt. And he was wearing that shirt. I was very involved with the Independent Restaurant Coalition and I realized, “Oh, actually maybe we can use this to do good.” So I asked Jake if we could make the shirt and sell it to fundraise for the Independent Restaurant Coalition to help restaurants devastated by the pandemic. And he thought about it for half a second. He was all in from the beginning. Our first run, we made 250. And we thought, “We’ll sell 250, that’s great.” We sold 4,000 in a month and we had to cut it off, because it was too much. And we raised over $90,000.

TUPPER: And six months later, they were calling it “delicore.”

NEVINS: Of course they were. Before I let you both go, what are your go-to orders here?

TUPPER: Toasted bialy, butter, and pastrami sandwich.

FEDERMAN: It changes, but for me, perfection is a sesame bagel, scallion cream cheese, nova, and salmon roe.

NEVINS: That sounds so good. Finally, what’s your favorite Yiddish phrase?

FEDERMAN: I like schep naches. When you’re proud of someone and you’re taking pride, you’re schep naches.

NEVINS: There you go. You ought to be.

FEDERMAN: I think our respective ancestors are proud we’re sitting around this table right now and keeping this alive.