ROLLING

How Aidan Zamiri Made the Music Video Essential Again

Aidan Zamiri spent the last year deep in the trenches of pop culture, shaping some of its most memorable visuals. Take Charli XCX’s “360” video—a whirlwind of cameos, biting humor, and perfectly controlled chaos that launched Brat summer. Or his work with Billie Eilish on her “Birds of a Feather” video, where haunting, dreamlike imagery gave an added layer to her sound. And then there’s his most recent work with Timothée Chalamet, like his Rolling Stone cover shoot and an instantly viral 14-minute Instagram livestream that blurred the line between spontaneity and performance. To take stock of his very big year, Interview’s editorial director Richard Turley connected with the Glaswegian artist to talk about their recent collaboration, the shrinking economics of music videos, working with pop stars, and what it takes to keep your head above water when the work—and the internet—never stops spinning.

———

RICHARD TURLEY: Aidan! What a year you’ve had! You really strapped yourself to a rocket, didn’t you?

AIDAN ZAMIRI: It’s been a year of lime green. A very cool year. I had no idea things would unfold the way they did. I don’t think even Charli [XCX] realized how things would play out.

TURLEY: You never know till it drops. You have hunches, but you never know. I always thought her level of unapologetic ambition and drive is very un-English—she has this clear direction and knows exactly where she wants to be. It’s very inspiring.

ZAMIRI: Yeah, she’s really smart—not only incredibly creative, but also business-savvy. One of the reasons I found it so easy to work with her is that she has an honest understanding of herself. She’s very aware of the cyclical nature of fame and the pressures that come with it, that there’s a fine line between adoration and criticism.

TURLEY: Absolutely. How involved is Charli in the creative process?

ZAMIRI: Extremely. It feels like we’re doing it in tandem. She’s actively involved in every decision. It wasn’t the usual back-and-forth with labels, where you go through layers of people and end up with scattered feedback.

TURLEY: The groupthink.

ZAMIRI: Yeah, and I’ve been lucky to work with a lot of independent artists who run their own operations. The communication is more direct. But with Charli, it was on another level— she knew exactly what she wanted and was able to make it happen. It feels like she’s using the system to get the support and resources she needs, but everything is still on her terms, which is really cool. It’s been amazing to be part of that journey.

TURLEY: How did you first meet her?

ZAMIRI: What’s funny is that I had been a fan of hers for a long time. I actually watched her play a set at T in the Park, which is a music festival in Scotland, around 2013 or 2014. I’ve been riding for Charli since the start, but we officially met a couple of years ago. I had worked a lot with Caroline Polachek, and they’re friends, so she made the connection.

“360” video, directed by Aidan Zamiri.

TURLEY: Was there an overarching plan for Brat from the get-go?

ZAMIRI: Well, she was going to do one video, the “Von Dutch” one, with another director, but she asked me to work on the second video. She sent me the song, “360,” and I remember hearing it and thinking, “This is such an insane song.” The chorus was wild, but it had this amazing energy.

TURLEY: How did all those cameos come about?

ZAMIRI: We kind of wanted it to have a campy vibe, like an old Eminem video where he’d play characters like Britney Spears. It’s almost absurd, all these name drops in the song, so we needed to embrace that tone. We wanted people with substance, people who had a bit of a specific following on the internet or lore to them. The way it worked out with Chloë [Sevigny] was almost surreal. Charli had a friend who had a friend, and through some crazy degrees of separation, we ended up contacting Chloë. She was in L.A. for a project, and her one day off happened to coincide with our shoot.

TURLEY: Sometimes it really is just about the moment. Right time, right place, right feeling.

ZAMIRI: Yeah, it’s all those serendipitous moments. I mean, we were really surprised—Charli and Chloë didn’t know each other before we shot the video. It’s so cool that she agreed to do it. As the cast grew, the video could have started to take on this obnoxious quality with all the name-dropping, but I think the prologue we shot to the video really helped set the tone with that unserious, parodistic dialogue. We wanted to make sure it didn’t come off as, “Look how cool we are.” It was important to show we knew it was a bit silly.

TURLEY: The whole thing felt very considered from the outside. That choreography of names, bringing different fan bases and audiences together— it felt familiar to what we do at Interview actually.

ZAMIRI: It’s like community-building, which really worked. People can feel like they’re part of it. That’s been a huge part of the success—the collaborative element. It’s one of the biggest reasons it resonated so well: “Brat belongs to everyone.”

TURLEY: Yeah, it’s smart. Placing ideas into culture now has the appearance of happenstance and serendipity with the hope of it coming across as being a product of organic reach. But really, it’s a lot of puppeteering and calculated roll out plans and seeding strategies. Even then, you need a lightness of touch.

ZAMIRI: I think it’s often about being visible enough that people remember you, but not overexposing yourself. There’s a fine line. You go from everything to nothing in the blink of an eye. A big part of success is being able to ride through the ups and downs and figure out how to sustain it. For me, when things started getting bigger, I became more aware of the attention, both positive and negative. Before, I was in this specific niche audience, and everyone who saw it probably understood what I was doing. I understood that more eyes on it meant more scrutiny, but it was tough to navigate. It felt personal, and everything started to feel a bit overwhelming.

TURLEY: How did you deal with that?

ZAMIRI: Well, I remember talking to Charli about it, and she told me, “You just have to accept it and move on.” I suppose if no one hates what you’re making, it means no one cares.

TURLEY: I think that’s almost understating the importance of negativity’s part in the process. You define your success by the antipathy and hate leveled at it, as much as the love. In fact, I think you only know it’s working when the haters get on board.

ZAMIRI: Absolutely.

TURLEY: Let’s pivot a bit and talk about how you manage your career. You work closely with influential artists, shaping their aesthetics. One problem for creative practitioners working in that environment can be that your aesthetic gets melded too far into theirs. How do you maintain your individuality without getting too caught up in anyone else’s world?

ZAMIRI: That’s a good question. It’s funny because I realized along the way that, especially when I get really connected to one artist, it can feel like everything I do starts to look the same. Working with artists is a big part of my career, but I’ve been able to maintain diversity because I feel like I make things with people, rather than trying to stamp my name or identity onto someone else. Every project feels bespoke to that specific story.

TURLEY: You’re able to work in a lot of different environments, also. I imagine that helps.

ZAMIRI: Exactly. I hop into commercial projects, do some editorial work, sometimes music videos. Something I’ve realized is that people forget things quickly. Brat was astronomically huge, and I know I’ll be connected to that for a while, which is awesome. But, for example, when “360” came out, people messaged me saying, “Is this the first music video you’ve directed?” And of course, it wasn’t. People don’t necessarily keep track of everything. They move on quickly.

TURLEY: Is that freeing or frustrating?

ZAMIRI: It’s freeing. I’ve learned to focus on each project as it comes and let it exist within that space. For example, when I started working with Billie [Eilish], I didn’t expect it to look like anything else I’ve done. It’s been funny because now a lot of my followers are Billie fans, and whenever I post something, the comments are flooded with people from her fanbase. A lot of people say we look alike so now anytime I post a picture of myself, I receive a flood of messages saying “boy Billie” and “William Eilish.” These things just kind of evolve, and I end up moving through them, always curious about what the next thing will be.

TURLEY: How do you choose the next thing you’re going to work on? Is there a specific criteria you use to decide what to take on?

ZAMIRI: When it comes to music projects, I won’t work with an artist unless I’m a fan of their work. Music videos, especially, aren’t really a source of income for me—it’s more about the creative process. I can be more selective. It’s really about working with artists I believe in. I have to understand their history, their narrative, and feel connected to their story. Early on, when I started doing creative work, I took on everything that came my way, just out of excitement. Over time, it became clearer what projects truly inspire me. So the criteria for editorial projects is that it has to feel authentic to me. But I also do commercial work throughout the year, and it’s interesting how now more than ever there’s a crossover between commercial and creative work. For example, the project I did with Gabriette for Nike felt like a cool blend of commercial work with proper money in it, but still maintained an authentic feel. When I do commercial work, I know that I won’t always have the final say. It’s a product or service I’m providing, and I’m fine with that. Commercial work allows me to maintain that balance: it’s not about compromising creativity but knowing when to step back and understand the bigger picture. And by doing that, I get to continue working on the personal, more creative projects I really care about.

“Guess” directed by Aidan Zamiri.

TURLEY: Yeah. People think just because you work with those big artists that there is tons of budget floating around, but often the opposite is true. There’s certainly money around, but not so much in music promo projects in my experience. That marketing money is spent on touring and pumping the social reach, not so much on the creative. I expect record companies guess that young creatives need to work for these artists more than the artists need them, so the power dynamic is kinda fucked.

ZAMIRI: Budgets are definitely shrinking, and it’s becoming harder to make money from music videos, to the point that almost every time I take on a project, I know I’m not going to make money off of it. From my limited experience, it seemed like things really changed during the pandemic. Labels saw that they were getting the same amount of views and engagement from videos that cost a fraction of what they used to pay. I talk to directors who worked in the ’90s, and they say the industry had much more money back then. They were able to do huge projects for relatively underground artists. The landscape has completely shifted, and people outside the industry might not realize that music videos aren’t what they used to be. There’s no longer the time, money, or resources being put into them. It’s a grueling process because you’re always up against tight deadlines and limited budgets. I think the only reason anyone does music videos is because they truly care about it.

TURLEY: I totally understand. When I framed the previous question, I wasn’t trying to criticize the music industry. I was trying to highlight the fact that nowadays if you want to have a creative career, your passion projects are one thing and the work that pays the bills is another. The big change in my lifetime, though, has been what constitutes a passion project now. I guess people would be surprised that music videos for major labels fall into that category for you, but value in creative work is slippery. It’s not as straightforward as people believe it should be.

ZAMIRI: It’s surprising for most people to confront that truth. Music videos, they’re often viewed more as commercials than as artistic pieces. But that’s the reality now. It’s a bit of a double-edged sword.

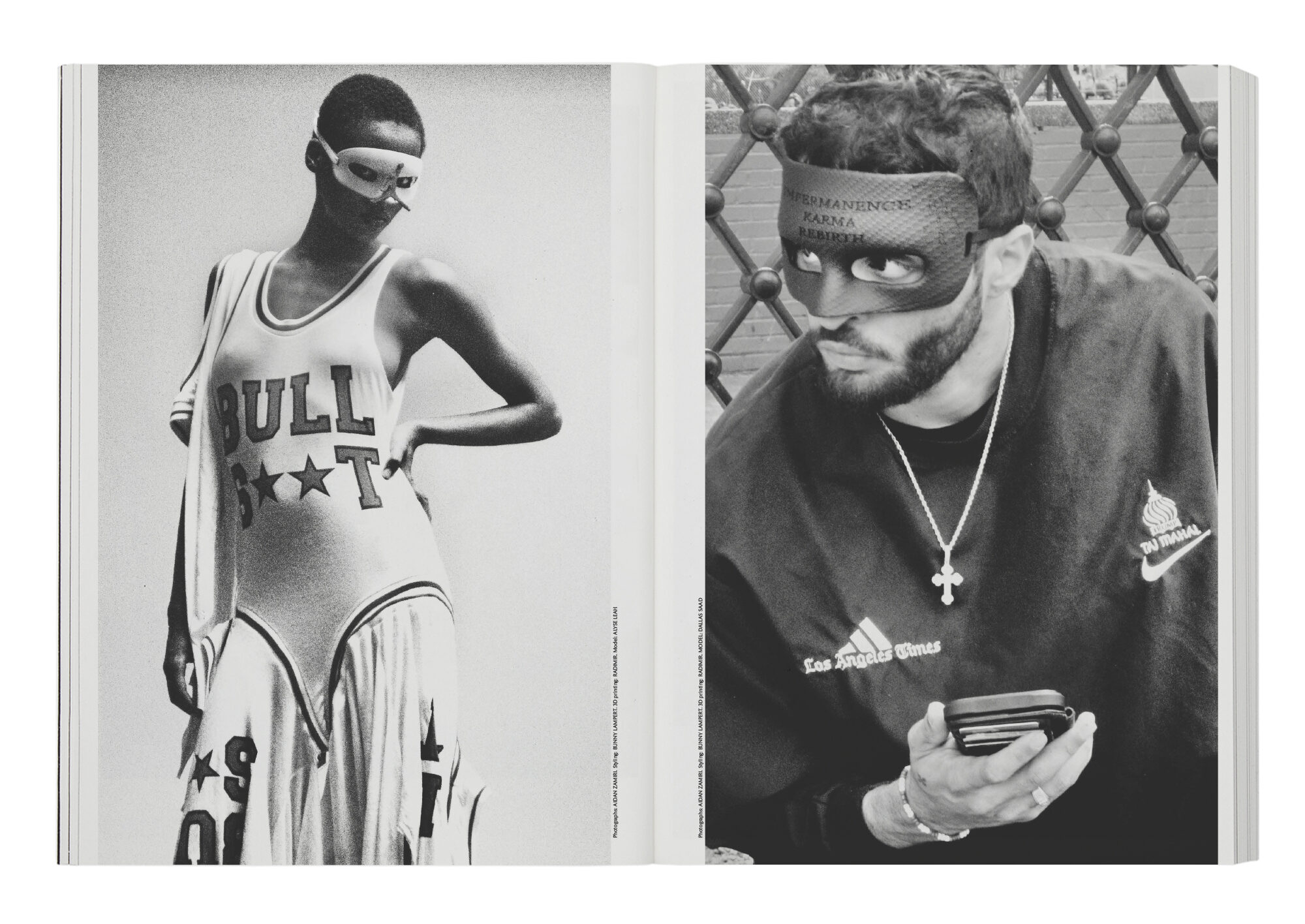

TURLEY: Can we peep in your process a bit? You mentioned that you create a lot of work and enjoy that aspect of producing consistently. It’s been interesting to see you work, and it’s especially interesting to see the evolution of your ideas since we’ve done a few things together. The masks that appeared in Nuts showing up in the Rolling Stone Timothée Chalamet shoot in a slightly different form, and I love that.

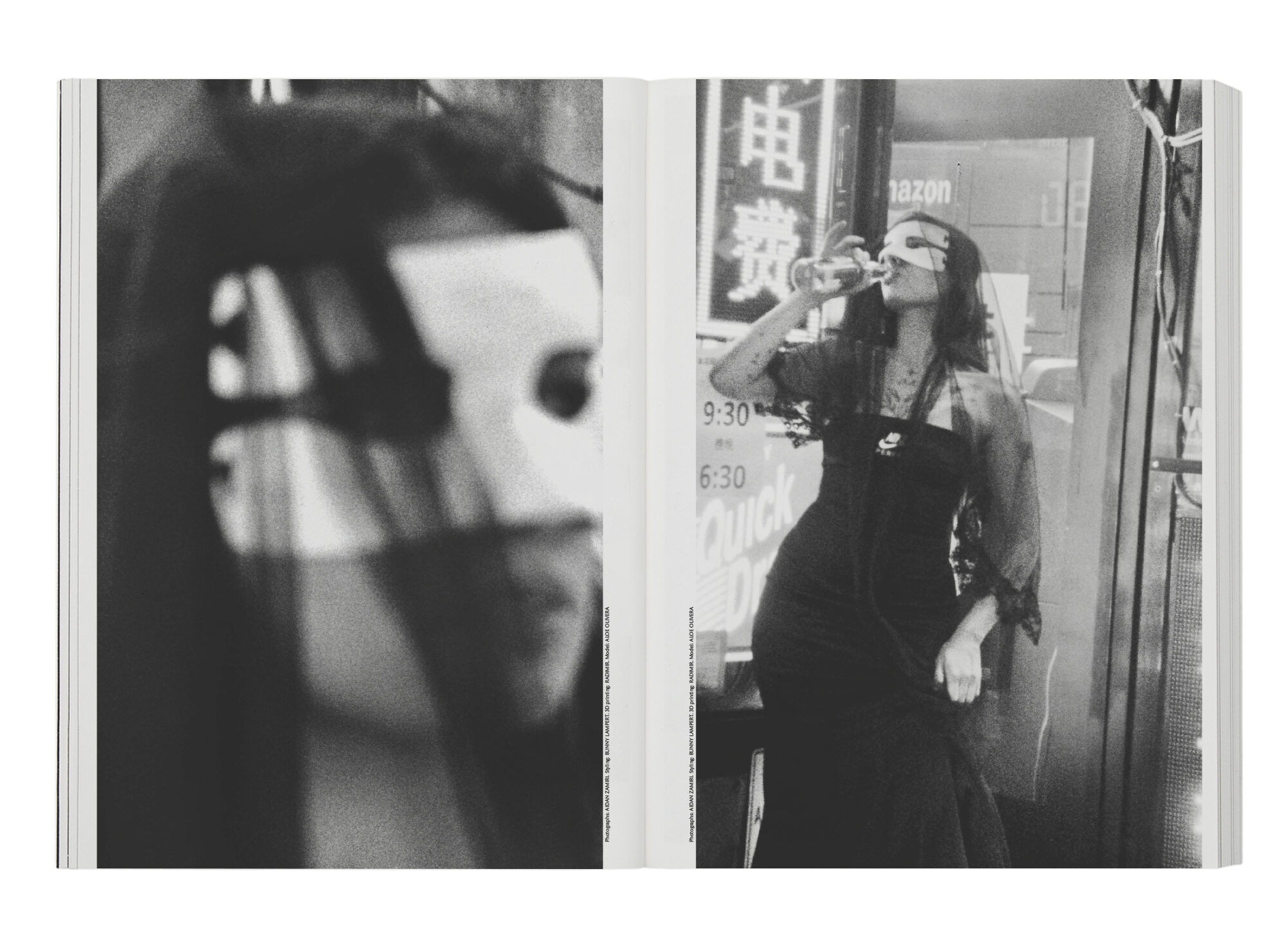

ZAMIRI: The process behind that, especially with the masks, was really freeing. What I love about projects like Nuts is that they allow me to explore poetry through images. In some other projects, when I’m working with talent, the focus is on their story, and it’s about making them look cool or telling their narrative. I don’t always want to project too much of my own vision onto that. With Nuts, I was able to make something without limitations. It became more about the movement of the people and the words, rather than fitting the work into a specific narrative or brand vision.

Aidan Zamiri for Nuts

TURLEY: That’s exactly why I make things like Nuts. They allow me to think freely, selfishly almost.

ZAMIRI: Exactly. It’s such a freeing process, and it really reminded me of what I find most interesting in my work: no parameters, no pressure, just the freedom to create. I’ve always been a bit neurotic, constantly thinking through ideas over and over. What’s been helpful is that doing commercial work brings me back to reality and helps me make things more accessible and straightforward. The process of distilling all those over-thought ideas into something more concise and impactful has been really rewarding. I think a lot of my work, especially since the first mask shoot, has fallen under this umbrella where it’s real, but also feels slightly twisted or abstract. It’s expressive, accidental, and a bit volatile.

TURLEY: For both issues of Nuts, we got your shots pretty early on in the process, so those little accidents ended up being codified and influencing the flow of the issue. For me right now, bottling the moment is central to a project being interesting. A spontaneity—focusing less on the subject, and more on capturing what was happening in the moment. The insecurity, the doubt. To capture the air in the room, and give feeling to that by layering over words and deciding how the pictures are sequenced.

ZAMIRI: What felt so vital about it was the lack of perfect composition. Normally, in a studio, everything is planned and tweaked until it’s “just right.” But with these shoots, we were playing with this reality of staging and improvisation, of performing and not performing. People were there by accident, some were falling over, others were just being.

TURLEY: It was like photographic autofiction. Real but never having happened.

ZAMIRI: Yes! That’s exactly it. It was real and at the same time, it wasn’t—just like the world we live in now. It’s a weird blend of truth and fiction. And the way we worked together made so much sense. I think a lot of it comes from my graphic design background, too.

TURLEY: Really? I didn’t know you were a graphic designer.

ZAMIRI: I studied graphic design, so it informs the way I think about visuals and how they interact with text. I love that a lot of the words we’ve used to shoot, or put on people’s bodies, aren’t perfectly crafted poems— like having “entrepreneur” on someone’s abs or “I love it here” on someone’s back. The images feel sweet, but also not. Somehow, there’s this new layer of meaning. That’s what I find cool about decontextualizing things—adding new context to ordinary stuff and making it poetic. It’s the same with this alt Instagram account I have. I just take pictures of cool signs or words I see in the real world. When isolated, they become really beautiful, even if it’s just a misspelled word on a shop sign.

TURLEY: Most language can become poetry if you allow it. A lot of Nuts, and my personal work in general, is obsessed with that. It’s about conjuring a mood and instilling a feeling in someone in a very indirect way. You might see a phrase that doesn’t really have any specific meaning without context, but when you place that word over an image, it becomes something completely different. And then, when you sequence that with the pages before and after, the whole thing creates new meanings. You’re not overtly pushing people one way or the other, but you’re letting them pick up on the cues. I want you to read and think with your belly, not just your brain. Capturing a mood, and forcing a feeling out of that captured moment— that’s what matters most to me. People often forget the physical experience of holding a magazine or a book. No one really thinks about how it feels in your hands, how it sends a message the moment you pick it up. I know it sounds new age, but fuck it. We don’t get that in the same way from laptops and phones.

ZAMIRI: Yeah, the feeling is all that really counts.

TURLEY: Actually, that’s a good segue to another thing I wanted to ask you about because most of your work is analog, right? Or at least, I’ve seen you use older technologies a lot in your work.

ZAMIRI: Well, I got into this rhythm of shooting in a way that was almost high-maintenance. It was really difficult—very specific lighting setups, shooting on film, using older cameras and all that. It was slow, expensive, and required a lot of manpower. So, as a way to disrupt that, I started working with older movie cameras. First, I love the way they look— crunchy and imperfect. It gives everything a filmic quality that feels strangely archival. Rooting things in that older or more nostalgic look allows me to bring in modern, mundane elements. For example, having someone not particularly styled in a very ordinary space, like a WeWork or something—it might feel mundane, but through that lens, it is romanticized. It makes it feel like something more. It Lana-Del-Reys it! The other thing is, working this way forced me to be way more brutal. I had to be okay with not knowing if I’ve got the shot or not. I can barely see if anything’s in focus. I just have to accept that I might not get it right, and I’m okay with that. It’s much more loose and immediate. The vitality of an image comes from that immediacy. Even the person I’m shooting can feel it. They know I’m taking a photo, but there’s no click, no flash—it’s almost like they’re aware of the moment too, and that interaction is what makes it special. It’s just going to happen, and you get all these accidents because I’m getting every frame of it. It’s almost like taking a live photo on an iPhone and finding that perfect frame—the one where someone’s eyes are half-closed, or they look away for a second. It’s way less stiff, you capture all these micro-expressions.

TURLEY: I love that. I also love that about films. I mean, I know this sounds new age again, but as I get older, I’ve become more aware of how important that is. Objects have a history attached to them. That piece of film was in the room with us, sharing the same molecules in the air. Looking at old photographs, you feel the energy of them, even if they’re technically crap pictures. It’s because you’re feeling something in your hand that is physically connected to the moment it was made. Plus now, we edit everything, we’re more thoughtful about what makes a “good” photograph. Back then, you just snapped a picture. The moment itself often ended up getting captured way more effectively.

ZAMIRI: Yeah, it was more spontaneous. And I think when you work with physical images, you have to consider the mistakes. That’s what’s cool about it. The technology isn’t adjusting everything for you—there’s no auto-correction. You get things out of focus, or a weird blur, and you realize, “That wasn’t the frame I thought it was, but that actually works.”

TURLEY: There’s that corny creative methodology about embracing mistakes, trying to engineer accidents. You can’t just keep doing what you know. If you only repeat what you’ve already done, you’ll never create something new. You need those mistakes to find something unexpected.

ZAMIRI: Exactly. It’s such a fun way to work. Even when things feel throwaway—I love taking an iPhone 4 photo and printing it large. Those tiny, imperfect images can look incredible when blown up. It’s funny how these things that seem disposable can turn out to be really beautiful.

TURLEY: Did you know that, every single picture we use for Nuts, we print it out big? We literally do what you just said. We print it out, scan, and work with those second or third generation images. People send us digital photos, but we always print them out. Everything is important if you let it be. So we’re always trying to physicalize everything—make it real on some level, give it meaning and memory, and hopefully ultimately, power.

ZAMIRI: It works so well. And with the words, having an entire page with just one sentence really makes you think about it, right? It makes you feel all the meanings in the sentence.

TURLEY: I’m not sure even I understand what all the words mean, but I know what they make me feel.

ZAMIRI: It’s really beautiful.

TURLEY: Thank you so much for contributing. It really means a lot. You’ve been an important part of everything, even if it’s not always intuitive. And working with Bertie, of course, is always a journey.

ZAMIRI: Absolutely. She’s been so instrumental in helping me understand the importance of finding the right words, bringing specific context to them, and finding beauty in the ordinary. She’s shown me that everything can be funny, tragic, or beautiful. She really has such a deep sense for that, and it’s been amazing working with her. She actually has a special thanks in the Charli video for coming up with a few of the ideas, including the moment where Chloë throws a cigarette into a trash can, which exploded into flames. We have such a similar sense of humor, and it’s amazing to have these conversations with someone who just gets it.

TURLEY: Yeah, it’s all about having that community of people you can laugh with. I hope you’ll get the magazine soon. You’ll see that piece Echo wrote about being photographed by you. It’s part of a group writing exercise. Everyone wrote a little something – I wanted to make sure everyone got their name mentioned somewhere in the magazine. The writing’s a bit different this time—less formal essays, more free association, just blocks of text. Wait, let me go find a copy of the book and read it to you. Here it goes: “Turn to the last image of the magazine. It’s me kissing my boyfriend, Gabriel, on the Chinatown rooftop right before the Nuts launch party. We never kissed in front of people, and we were there in front of people, who were just there to see us kiss. Most of the time, I see myself as a prop and I do whatever Aidan says to make sure the words are being seen. But from the moment I felt Gabriel’s lips, his body heat, his tight grip, because he’s also nervous like I am, I felt oddly calm and romantic. For Aidan, this might just be one of the million fighters he’s taking, but he’s stayed with me ever since. Every time I look at the book you’re holding, I see it again. It feels like I’ve got a matching tattoo with my boyfriend, it’s a permanent mark and celebration of my relationship. Standard magazines and textbooks may last 100 years before the paper begins to fall apart and acid-free paper is expected to last 300 years before deterioration becomes obvious. So depending on how far I’ll keep Nuts, my tattoo will live on for 100 to 300 years. Do I regret it? Not at all. It doesn’t matter if we end up being together or have a very ugly break up, there was a time we kissed. And we were so close to each other.” Isn’t that amazing?

ZAMIRI: My god. Yeah, it really is. It’s honestly so touching. I’ve never had someone write something like that about me. It really means a lot.

TURLEY: Yeah, it’s just so good. I think I ended up printing the same sentence twice, but I guess we wanted it to appear in a few different places. Some things just have value, you know?

ZAMIRI: Please tell her thank you a million times.

Aidan Zamiri for Nuts