ORAL HISTORY

“He Was the Center of Attention”: Basquiat at Area, by the People Who Were There

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Jennifer Goode, 1985. Photographed by VOLKER HINZ ©. Courtesy of the Volker Hinz estate, Hamburg, Germany.

On December 19, 1985, downtown New York’s cool-kid royalty congregated in a desolate corner of Tribeca to celebrate one of their own. It was Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 25th birthday party, and the night at Area was set to be as eclectic and intense as the man himself. Forty years later, Basquiat’s party, which he cohosted with Area cofounder Eric Goode, blends into the fabric of the club, where art exhibitions set the backdrop to hedonistic nights. Basquiat was a regular at Area, his spirit and style blending perfectly with the club’s rebellious environment. To commemorate his legacy, Dom Pérignon will be debuting their tribute to Jean-Michel Basquiat this fall. On the occasion of the maison’s limited edition that captures the artist’s lasting influence, friends like Kenny Scharf, Michael Chow, and Karen Binns share their memories of that time when creativity was the reason to celebrate.

———

DIANNE BRILL (“IT” GIRL): The clubs were the place that unified us as a group. A lot of us went out by ourselves and just met everybody there. You didn’t have to call ahead and say, “Are you going out tonight?” You just went and they were there. Once in a while Andy would pick me up, but generally we just would say, “Okay, it’s Jean-Michel’s birthday, let’s go.”

JENNIFER GOODE (AREA DESIGNER): I organized the party. I’m sure Eric did the invitations because he knew who he wanted to invite. I did the flowers for it, because I would always do flowers.

ERIC GOODE (AREA FOUNDER): Jean-Michel’s birthday was the 22nd of December, and mine was the 19th. So we would do our birthday parties together. That drawing he did, for whatever reason, was the invitation to one of the birthday parties.

JENNIFER GOODE: I put together a slideshow of photos of Jean-Michel and photos of Eric. I got all these slides from Jean-Michel—baby pictures, whatever he had. We had this projector in the lounge.

KAREN BINNS (STYLIST): I remember it being chaotic. William Burroughs was there in a wheelchair.

MICHAEL MUSTO (NIGHTLIFE REPORTER): The Basquiat party was not that huge to me. It was just another party. I went to Area probably three or four times a week.

CORNELIA GUEST (ACTRESS): I remember going with Andy [Warhol]. Eric Goode was unbelievable with all of that, because he had all those art installations. He made that place the most happening of all places, and it was really cool for all the artists to have their stuff out. He brought an incredible amount of awareness.

ERIC GOODE: The thing that brought everyone together in those days was Andy Warhol. People would come because of Andy.

PATRICK McMULLAN (PHOTOGRAPHER): I wasn’t there, or if I was, I didn’t know what I was there for. I do have a cool picture of Jean-Michel DJing with Francesco Clemente though, so who knows.

JENNIFER GOODE: It was nonstop work for all of us to keep the club running, and then in the middle of it, I fell in love with Jean-Michel. I hadn’t had any romantic relationships for quite a while. And then he came, and clearly he was the one. So I had to try to balance being with him and keeping the parties at the club going—what a life.

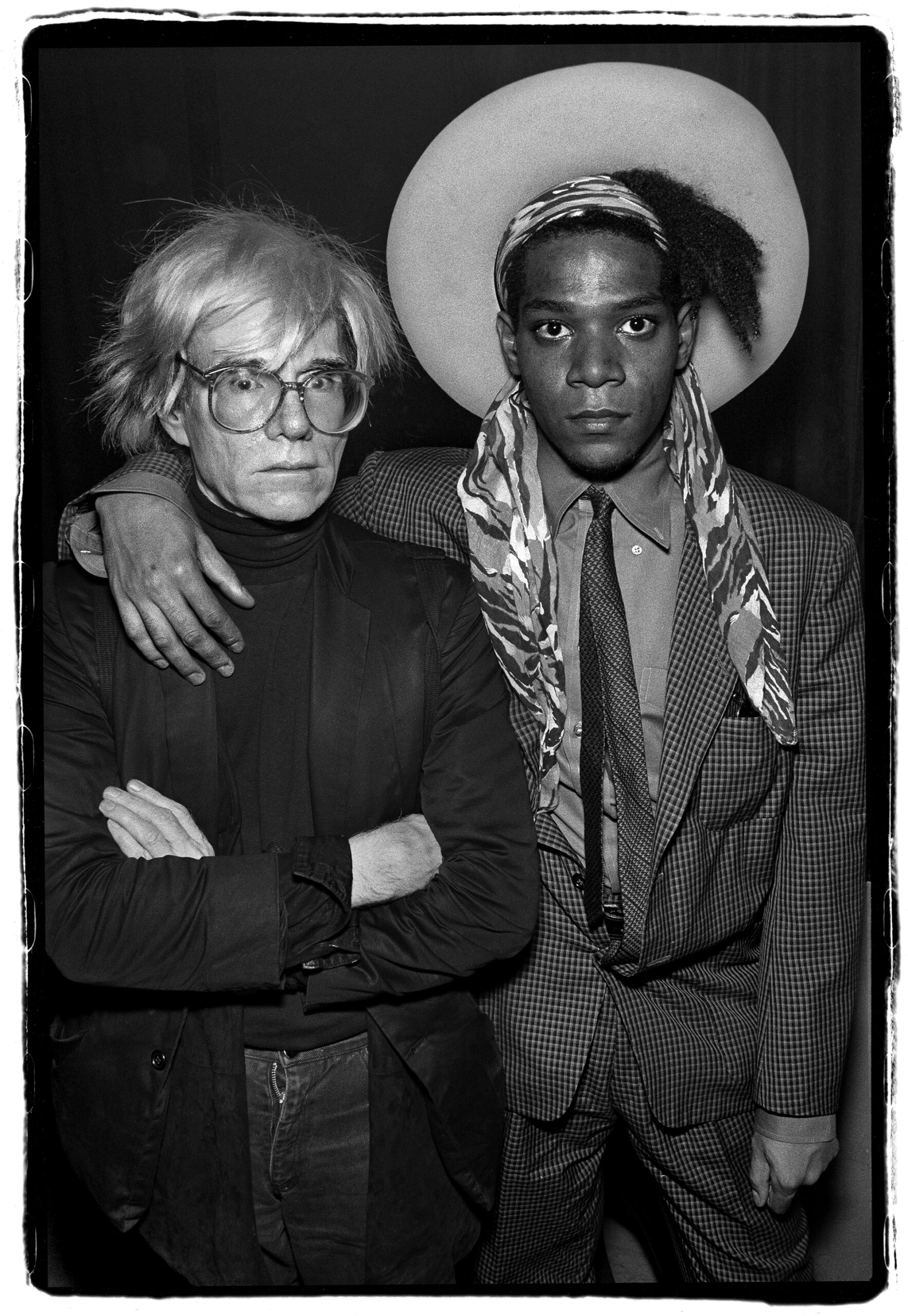

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, September 1986. Photographed by WOLFGANG WESENER ©.

TONY SHAFRAZI (GALLERIST): Area was on Hudson Street just below Canal. As you entered the building, there was a long corridor about 5 or 6 feet wide, with about 15 or 18 feet of glass vitrines on either side filled with different theatrical sets. These were quite impressive because you knew you were entering something visual—it made it more of an experience.

JENNIFER GOODE: Right next to Area was a food import company, and they imported olives, so there was a smell kind of like sour olives.

BINNS: It wasn’t as bitchy as Studio 54, but the door was just as intense, because the people that wanted to go there were coming from the Mudd Club—they were artists. I met a lot of actors, actresses, artists, and Upper East Side rich kids.

MUSTO: This was when Tribeca was pretty undeveloped, so it was pretty wild in the middle of this wilderness to see a street packed with people all dressed to the nines.

MICHAEL CHOW (RESTAURATEUR): Swinging London got to America with Studio 54, and then the Chow period picked up from that, and Area comes after that. It was the nightclub version of Mr. Chow.

MARIPOL (FASHION DESIGNER): There was no line, there was a crowd. In French, we call it physio for physiologist, the person that looks at your face and decides who can get in. In this case, it was pretty much everybody from downtown to midtown to uptown.

CHRISTOPHER MAKOS (PHOTOGRAPHER): Me and my crowd never had a hard time getting in because we knew all the players.

BRILL: Jean-Michel, Andy, and I used to hang out there all the time, but so did a million other friends. Some famous, some not, but all fabulous.

JOHNNY DYNELL (DJ): We would open at 11, which was a little bit late, because other clubs like Daneteria would open at 9, but they never would get going until 11 or something. It was like, “No, we’re not going to do any of that. Just open the door.” Area was more about the art than making money. That’s why it was so great.

JENNIFER GOODE: I met Jean-Michel at Area. He did not have to stand in line, because the door people knew him. He would come in for half an hour. It was just part of a circuit. Then he’d go to other clubs.

KENNY SCHARF (ARTIST): Area was a step up in professionalism, as the art place. Before then, it was just like hot glue—it wasn’t so evolved. It was a lot more conceptual and just more together, let’s say.

ERIC GOODE: Area was about blowing people’s minds and doing things that were really interactive and crazy. When we did the Carnival theme, we had carnival rides. When we did Sports, we had a trampoline on the dance floor, and people would be so fucked up doing flips on the trampoline. It was insane. People refer to Area as an art club, but it was really a club about ideas, not about creating commodities, which the art world did.

SHAFRAZI: Young, up-and-coming artists were given the opportunity to do something creative even before galleries were involved. So suddenly, going to the club offered you something besides just dancing. And then the emphasis on the visual experience also became even larger at Area because the space was bigger, and they were willing to spend a little money on sets and structures, as well as DJs and performers. Suddenly, there was a very interesting crossover between the experimental and professional, especially when it came to DJs.

Johnny Dynell in the DJ booth at Area, July 4, 1985. Photographed by WOLFGANG WESENER ©.

DYNELL: Justin Strauss and I were the DJs. I did the openings when the themes would change. Sports was a good one. It was where they put a swimming pool on the dance floor. In the beginning of the night, I would always play music to go with the theme for the first hour or two, until it got really full. For Gardens, it was Antonio] Vivaldi, and for Suburbia I played Bruce Springsteen and stuff. It was just to set the tone. You could really go there, but only for an hour. Then people wanted to dance.

JENNIFER GOODE: Jean-Michel was DJing that night. Probably everybody was exiting that lounge because what he would DJ was very eclectic. It was jazz, it was be-bop, reggae—which people could probably tolerate—but when it got to some of the jazz, no.

DYNELL: He was such a character. He would be playing John Coltrane, just crazy stuff. [Laughs] And everybody would be like, “Oh god. Can you tell him to stop?” And I would say, “Jean-Michel, you can’t play Charlie Parker. And he’d be like, “If they can’t dance to Charlie Parker, then they can’t dance.”

BRILL: Something very weird happened. When he was DJing, the dance floor was slick for some reason. Oh my god, am I dreaming? Somebody had spilled something, but it was not like a drink. It was some weird-ass thing. Something had people slipping and falling.

BINNS: He liked jazz, liked reggae. He liked rockers, a bit of classical. He liked a bit of hip-hop, but he could barely dance.

BRILL: He took DJing very seriously, as seriously as his painting. He was a musician. People say he wasn’t good, but I thought he was cool. And back then it was harder. You couldn’t talk to your friends when you were trying to switch records. Forget it.

DYNELL: Jean-Michel had really, really, really good dub reggae, too. But he was a big pothead, so it made sense. He really liked his weed.

MARIPOL: He used to love to play on 78 tracks, a regular record, so you can imagine the sound. Then he also would love to break them by throwing them down. He was very goofy, meaning he loved to play jokes, and he loved to laugh.

CHOW: And by the way, all that rap music, Jean-Michel started scratching the records and all that fucking shit.

BINNS: He danced, not like Pee-wee Herman, but he would dance and laugh at it. He wasn’t a dancer dancer. He would dance as if it were a joke, like a puppet. As if he’s too cool to dance. But there was a charming playfulness about him; you’d look past all that.

SHAFRAZI: By ’82, when he walked into a club, the whole thing would go silent for a moment. The whole thing came to a standstill, and then picked up slowly. He was the center of attention.

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Tina Chow, Area, May 1986. Photographed by WOLFGANG WESENER ©.

MUSTO: He was so hyped at that point. He had been, I believe, on the cover of The New York Times Magazine. It was clear that he was the biggest “overnight” art superstar.

DYNELL: At Area, the people like Jean-Michel, Francesco Clemente, Andy Warhol—the artists—they weren’t just celebrities at the club. They were part of the club. They would go there pretty much every week.

SCHARF: I had been involved with nightclubs and art way before Area; it’s just what I did. There weren’t galleries that said, “Oh, we want your work.” We were all making art and showing it on the street or in nightclubs.

SHAFRAZI: The friendship that suddenly sprung up among, especially among these three—Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf—was irreplaceable. It was an amazing kind of mutual respect and dignity.

SCHARF: I knew Jean probably before anyone here. He was 17 and I was 19. And then right after I introduced him to Keith Haring, and in a matter of minutes, he was with the whole downtown scene. It happened very quickly. He was an amazing and intense guy, and his art shows that.

DYNELL: I remember I kept seeing “SAMO©” written all over the place. I’m going, “What the hell is that? Copyright? S-A-M-O. Same old, same old, same old. And then it started to expand, then he started the “Origin of Cotton” with the same O. I was like, “Who is doing this?” And then at the Mudd Club, Michael Holman or Vincent Gallo was like, “That’s Jean-Michel, he’s Samo.”

MARIPOL: A lot of journalists always ask me, “What’s your first memory?” And it’s very hard to pinpoint the first memory of somebody that you’ve already known because his writing was on the wall.

SCHARF: He was amazing to watch in action. There was this power and this crazy energy off his line. And that’s why even though he has been gone for so many years, his art is still so powerful, because that energy is something that he applied, and it keeps coming out from his work.

CHOW: Jean-Michel was the coolest motherfucker in the world. We bonded. We have a common thing, which is dealing with injustice. He’s expressionist, I’m expressionist. What do expressionists do? They deal with injustice as their soul-searching richness in order to create incredible works of art, to harmonize the world, to make peace. In other words, it’s the antidote to all the atrocities of the world.

BINNS: We had a lot of anger that we both agreed on. We had a lot of self-pride as Black people in the downtown scene.

CHOW: We bonded mostly because I was so connected. But he and I, we are the quintessential anti-racist motherfuckers. He’s so angry. And I’m of course angry. So all that anger, all the soul-searching, all that pain is very useful fuel to become the greatest artist in the world.

Jean-Michel Basquiat DJing the party for Keith Haring’s Pop Shop at Area on April 17, 1986. Photographed by PATRICK MCMULLAN ©.

MCMULLAN: Andy was the big artist, and Andy loved Jean-Michel. And so when Andy was like, “No, this guy is the best. He’s the best,” then we all were like, “Oh, I guess he really is a big artist, then.”

ERIC GOODE: Andy got a bad review in the Times, and we were sitting there for brunch at the Odeon, and he was kind of depressed. I remember he said, “I really need to do something with this younger generation.” It was the beginning of his collaborations with Jean-Michel.

SHAFRAZI: Warhol became so enamored with Jean-Michel. That led to them working together, which led to the collaboration paintings.

DYNELL: He was a little rogue-ish, but you could see the talent. You’d be talking to him and he’d be staring off into space. You’d be like, “Okay, Jean-Michel, where are you now?” And who knows where he was? But he did smoke a lot of pot.

BRILL: He was extremely handsome and relatively tall. Not weird tall, but tall. He had really good taste and it was like he was holding something back when he came into the room, which is always attractive-when you feel someone has a thought on their mind. And he had an earthy scent about him. I don’t know what perfume he was wearing, but it was something nice about the way he smelled. Chicks loved him.

MARIPOL: I don’t think he was running around to pick up girls. He and Jennifer [Goode] had a steady relationship. But if he was DJing, he was just happy to put the music on. If he wasn’t DJing, he was an observer.

MCMULLAN: He was somewhat Sphinx-like, in the sense that he didn’t seem like somebody to easily know.

JENNIFER GOODE: He was known by anyone in the downtown scene, except for me. I had not a clue who he was when he walked through the door. But anyone in the scene knew. He stood out. He’s beautiful, dressed impeccably, and kind of shy. He wasn’t an extrovert, but people were just attracted to him. He just had this sexy, interesting aura.

CHOW: He was a killer. This guy, he was too human. I fell in love with him.

MUSTO: I never actually met Basquiat. I was always afraid to talk to him.

SHAFRAZI: Everybody was curious about him because his look would change every week. His smile and his looks and his charm were rather remarkable. His attentiveness— his curiosity was absolutely unforgettable.

SCHARF: Jean-Michel was the big star first. He was the first one to be flying to Italy and come back with cash in his pocket.

MARIPOL: I remember Jean-Michel’s father being there. He loved to invite his father out. He was so proud. He said one day, “Papa, I made it. I’m famous,” or, “I’m rich,” or whatever.

BINNS: He always gave the homeless food, because he said one time he was there.

DYNELL: One thing I really liked about Jean-Michel, and Keith was like this too, was when they started to become rich and famous—champagne was the big thing among the art dealers [and] Jean-Michel always bought bottles for the kids, the young artists who couldn’t afford it. He wanted people to have a good time and he knew what it was like to go to a club where the rich people are drinking and you’re just scrounging for drink tickets. He never forgot that.

MCMULLAN: Eric would often be there, and he would have drink tickets. It was a drink-ticket economy. You could have 10 drink tickets in your wallet and you’d feel rich.

ERIC GOODE: I would give people drink tickets, people that I thought were important, and I’d give out way too many. So if you got in free and you got drink tickets on top of it, you were, like, important. And so it was 100 percent a drink ticket economy, because people didn’t have money. That night I was a chicken with my head cut off, running around, making sure it was all going well.

BINNS: I would stand at the bar next to Jean, and then I’d see someone like Lauren Hutton come in and drink whiskey, and Jim Jarmusch would be sitting at the same table. Everybody just happened to be there.

Maripol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Tier 3 nightclub, NYC, 1979. Photographed by EDO BERTOGLIO ©.

DYNELL: There were movie stars there, but Area wasn’t about that. I do remember a couple times in the lounge there was a roped-off area, but usually everybody was just all in the club.

BINNS: We didn’t really care about the VIP. The VIP was way in the back. People were on the dance floor, and in the lounge, because the lounge was always cooler. They would have someone standing there with some crazy outfit on, playing a flute, or jumping up and down on a trampoline, doing some mad shit. That’s where everyone would talk and congregate and hang out and smoke and drink. And the other room was a big dance floor.

MUSTO: There was a VIP, but often it was self-servicing, in that there wasn’t always a door person with a list. I would push, push, push to get to the back area, and that’s where most of the art exhibits were. That’s where the “VIPs” were, whatever that means. We were all competing for the cameras of Patrick McMullan and the others who shot for Details.

MCMULLAN: That was my job, working with Stephen Saban for Details. I was always getting invited to go to things, which I just went to. But there was a guy, Ben Buchanan, who was an official Area photographer.

BRILL: We were all part of this one team that we called then the Fab 500, which was made up by my husband Rudolf [Pieper], who owned Danceteria. He made it up from the mailing list of the 500 people we thought were the best and most fun to be around.

MARIPOL: You could see stars, but you didn’t care that they were stars. There weren’t a lot of paparazzi there. It was more like a family club for us.

BRILL: We made a tribe of people. We’d see someone from across the room, and then somebody would join you on the dance floor or you’d run into them in the bathroom because the bathroom was like a VIP area. You’d never go pee in there.

MARIPOL: It was the first time that we had a unisex bathroom and it was a wild scene. Stephan Lupino was always taking pictures in there and wanted girls to show their tits. I was one of them.

DYNELL: Some people would dress for the themes. Say if the theme was gnarly, they would dress very grungy, skateboardy. And then you had Malcolm McLaren’s Madame Butterfly Ball, which people would dress more formal for.

MARIPOL: It was a continuation of Halloween, if you ask me.

John F. Kennedy Jr. waiting to get into Area. Photographed by RICHARD PANDISCIO.

BINNS: The people that went out weren’t generic. Everybody wanted to be an artist, number one.

MUSTO: I feel that Jean-Michel liked Area because it had some of the feeling and the aesthetics of the East Village art scene, but in a big glossy disco.

ERIC GOODE: I knew Jean-Michel before any of the fancy clothing, in the Samo days when he would just wear the same overcoat every day, before he was with Mary Boone. Then he started going and buying suits at Comme des Garçons.

BINNS: Jean-Michel was the best-dressed guy in the city. His taste was flawless. Even when he was broken down, he looked doper than anybody in the room.

MARIPOL: I think it was in ’85 that he did a fashion show for Comme des Garçons in Paris. It’s not a myth that he was painting in an Armani suit. They called it grunge, mixing designer with non-designer. He was not a fashion geek but he was naturally stylish. He never wore jeans, but the pants were baggy.

BINNS: He was an extreme beatnik Bohemian man. He was, to me, like the Black Picasso. He was the one that would wear the trousers that he was painting in for two days, put a blanket around his neck, slide on some slippers, and say, “Let’s roll” He was extremely decadent, it was all very natural.

GUEST: Eric really brought the art scene in. Fashion was much easier to bring in than art—fashion, you could wear. Kenny Sharf and Jean-Michel and Keith and Andy couldn’t carry their paintings on their back. So what Eric did with the installations was completely different. No one had done that.

ERIC GOODE: People sometimes say the nightclubs were laboratories for ideas. They were, to a degree. I think Area in particular was.

MAKOS: Area was a celebration of who we all were collectively—like the art scene, the music scene, the fashion scene. It all came from the ground up.

Stephan Lupino and Tony Shafrazi in the men’s room at Area. Photographed by BEN BUCHANAN.

ERIC GOODE: The reason we did Area was because we were interested in ideas. We thought the art world was really pretentious and boring, and people wandering around with white wine at an opening trying to be sophisticated. We thought, “Oh, it’s the monetization of the art world. This is just about money.” We were interested in things being ephemeral, and so Area was the antithesis of the art world.

MUSTO: Palladium took note of that and became artistically driven. There was the Kenny Scharf room and there was a Keith Haring mural on the dance floor, and there were the Basquiat murals in the Mike Todd room. It was geared more towards people in New Jersey to come in and get a feeling of the exciting art scene that you’ve read about.

DY NELL: By the time the Palladium opened, they were hiring Kenny Scharf to do a room, they were hiring Francesco and Keith Haring. That was a whole different thing than at Area, where the artists were really part of the community.

ERIC GOODE: Area opened in 1983, and by 1985 it was kind of the peak of that moment in time in every way. You know how nightclubs in New York typically have an arc to them? They’re red-hot, and then they tend to fizzle out.

MUSTO: In ’87, I wrote a cover piece for The Village Voice called “The Death of Downtown,” about how the club scene had gotten so big that it imploded. And also Andy Warhol had died at that point, and he was kind of the visionary that determined what was hot and what wasn’t, just by being at a club. If he was there, you knew you were at the right place.

ERIC GOODE: I think Jean-Michel looked up to Andy like a father. I will never forget when Andy died. Jean-Michel was absolutely devastated.

BINNS: Andy was his protector. Nobody could get away with any-thing. When Andy was alive, he’d be like, “What? No. What you need to do is pay him what he deserves.” Even when they did that show, it got slaughtered because people were jealous of it.

GOODE: “We’ll do this until it’s not fun.” That was our business model. And it became work to get people to come to our club when Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager got out of prison and went off to build their mega club with $12 million. We built Area for $200,000. And they studied our club. They were there every night, and unlike when they had Studio 54, they realized, like, “Oh, wait a minute. There’s this thing called art stars.” But they totally misunderstood Area, because we weren’t really about art at all. We were about ideas.

DYNELL: Where are the new Keiths? Where are the new Jean-Michels? Where are the new Kenny Scharfs? The kids are still having fun, but where are the new ones?

BRILL: We were looking for each other our whole lives, sitting in our rooms feeling like, “No one understands me. I feel so separate from everybody.” And then here we walked into a place that felt like every breath we took, we were cool. We were so excited to be with each other. And very early on, Jean-Michel overshadowed his work because we all did work and we were all pretty good at what we did, but with him, we very quickly realized, as important as he was to be in the room as a person, his work was bigger. I think we knew it was, but we didn’t know he was going to become that.

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Eric Goode. Photographed by VAL SHAFF ©.