Gillian Flynn Brings Her Mid-Western Noir to a Boil

In most bookstores, it’s a long walk from the literature section to the crime shelf. For those who don’t make a hard distinction between the two genres—who, in fact, consider crime stories to be of a piece with some of the best literary works—the writer Gillian Flynn is evidence enough. The 47-year-old Kansas City native wrote the most compulsively read novel in recent history, 2012’s mind-bender of a thriller Gone Girl. But the runaway success of that book—and its page-turner plot appeal—does not diminish the ferociously brilliant prose that buoys each of those shocking twists and pathological character shifts. For those familiar with her previous books, 2006’s Sharp Objects and 2009’s Dark Places, Flynn’s ability to deliver literature with teeth is no surprise. She continually flips the pervasive narrative of the woman as victim to the woman as survivor—even if the transition isn’t always pretty. Flynn’s books are among the best at chronicling the fun house-mirror madness of the 21st-century American Dream. And now she’s gone and done the same with film and television.

When David Fincher was tapped to direct the movie adaptation of Gone Girl (2014), Flynn signed on to write the screenplay. She has since worked on bringing Sharp Objects to television with this year’s eight-episode HBO series starring Amy Adams. But this fall, with the release of the director Steve McQueen’s action heist film Widows, Flynn moves away from adapting her own material. In the film, led by the actress Viola Davis, Flynn creates a tough and turbulent present-day Chicago where a lot of money changes hands but very little of it ends up with the four women whose criminal husbands recently died in a botched robbery. Widows is based on a popular 1980s ITV television series, but the raw, clever courage of the female characters—who aren’t afraid to be antagonistic even when they’re the protagonists—is hallmark Flynn. She keeps the pace of this urban noir boiling, while notions of race, sexism, political maneuvering, and violence roar from all sides. You can tell yourself it’s pure entertainment, even though it’s so much more than that.

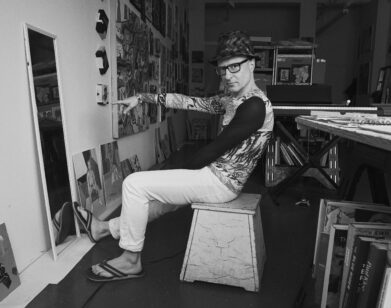

Flynn has lived in Chicago for the past decade, residing on the North Side with her husband and two children. That’s where we met up at a small café this past September.

———

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You grew up in the Midwest and, after years in New York, the heartland called you home.

GILLIAN FLYNN: I grew up in Kansas City and still get back a fair amount. But, yeah, I was dying to come back. I’d been in New York working for Entertainment Weekly and then in L.A. for a bit. When I first moved to New York, I started out in an illegal sublet in Stuy Town.

BOLLEN: Oh, god, introduction by Stuy Town.

FLYNN: I remember there was a single Cat Fancy poster on the wall. I was sure the guy who owned the place was a serial killer and was going to come back to kill me one night. [Laughs]

BOLLEN: Taking a job at EW, you were already moving in the direction of writing and film. Were magazines the gateway to books and scripts?

FLYNN: Growing up, my father taught film and theater, which is why I’m such a film-crazy person, and my mom taught reading, so I thought I’d follow in their footsteps. That was the original plan.

BOLLEN: You didn’t dream of being a writer?

FLYNN: I always wanted to be a writer, but if you’re from Kansas City, Missouri, you don’t ever tell anyone that. Because they’d say, “Your britches are a little too small for you.” In the back of my mind, it was always there. I even took a screenwriting class. And I’d gotten a journalism degree. But my first job was actually as a writer for a human resources magazine. In case you’re wondering, I know everything about family medical leave.

BOLLEN: So when you left EW in 2008, what was it about Chicago that attracted you?

FLYNN: I was starting to think where I could put down roots. I’d been bumping all around for most of my twenties, and I’d fallen in love with Chicago when I was at Northwestern for journalism school. For me, it was the city that got away. Chicago has parts in it that I loved about New York—

it’s a walking city with weird neighborhoods and museums. But as I always say, Midwesterners would much rather like you than dislike you. They don’t start a conversation with their arms folded. I like the laid-backness.

BOLLEN: I’d argue that you created a new genre of crime literature called Midwestern noir. As we both know, the Midwest is far more haunted and twisted than it gets credit for being. Were you always attracted to mystery and horror as a child?

FLYNN: I loved being scared as a kid. I loved the darker side of humanity. That was in my brain, even from a very early age. I was always thinking, “What could be the scariest outcome of this situation?” My cousins and I were kind of raised in a pack together—all girls. They always wanted to be princesses. I always wanted to be a witch. Or a killer. My head just went in that direction. Maybe because my father was a film professor, I developed a taste for Alfred Hitchcock. Films like Psycho scared me just the right amount. They didn’t haunt my dreams in a terrible way. I like that sensation of being scared. I’ve always been one of those people who wants to know what’s underneath the rock, what’s down the corner, what’s down the blind alley.

BOLLEN: Writing is such a satisfying way to harness those dark curiosities.

FLYNN: For Sharp Objects, I knew I wanted to talk about female rape and cycles of violence and what that looks like, which I just hadn’t seen in literature. I was an English major, and I went looking for those topics in literature in a realistic way, and I just couldn’t find them. That frustrated me.

BOLLEN: Is your brain constantly plotting mysteries? Actually, forgive that question. People never realize what slow, laborious work it is to build a plausible mystery plot. And it puts so much pressure on the end of book to upset expectations. You basically are required to out-trick 90 percent of the world population.

FLYNN: Despite what people might think from Gone Girl, plotting is not my forte. It doesn’t come naturally to me.

BOLLEN: Gone Girl is so ingeniously plotted. But what’s particularly impressive to me is the scaffolding of the book and how the conflicting narratives build and clash.

FLYNN: I think I went into overdrive. You start with a thesis that a woman frames her husband for murder and yet you want to discuss themes of marriage and gender. To make that thesis believable, you really have to explore what this character is doing and understand what type of personality spawns this sort of thing. It was like reverse-engineering a character, where I had to ask, “Who is this person?” I do all of my actual writing on my laptop, but I do all of my thinking and character development on sticky notes or yellow legal pads. My office at the time was in the basement of our Victorian house, and to get to it you had to go through this really creepy unfinished basement. Past my writing room was our guest room. It wasn’t the greatest place to take a guest. You’d have to walk through a room with notes hanging on the walls scrawled with words like “hatred” and “rage” and “Zima” because I had to fact-check when they discontinued making Zima. [Laughs] And that basement was never properly insulated, so I’d use a space heater all winter, to the point where my front was warm and my back was cold, like sitting at a campfire.

BOLLEN: So your houseguests would have compassion for your husband, thinking, “Oh, his poor mentally ill wife.”

FLYNN: Yes!

BOLLEN: Did the extreme success of Gone Girl freak you out at all?

FLYNN: I was never like, “Someday I’ll be number one on The New York Times Best Sellers list.” I wanted to be a well-respected writer who could make a living writing. And for my first two books, I was only making a living at it with my supplemental EW job. I thought having a magazine job and writing a book every few years was a great plan.

BOLLEN: Practical dreaming is so Midwestern.

FLYNN: But to answer your question, I am starting to get anxious because I haven’t published a book since Gone Girl, aside from The Grownup [her ghost-story novella from 2015]. I’ve done a lot of screenwriting, but that’s different.

BOLLEN: Are you now feeling cornered into the mystery crime genre, or would you be allowed to write a comedy as your next book?

FLYNN: I’m still figuring out my new one. I’m smack in the middle of writing it. It’s not a traditional whodunit, but it is a thriller. To be honest, I do think it’s written very loosely into my contract: “In the vein of Gillian Flynn.”

FLYNN: Maybe I was just sensitive. But I also got that a lot from older, well-meaning gentlemen: “I don’t normally read books by women, but I read this and I thought it was really good.”

BOLLEN: There is an expectation of what your books bring to the table.

FLYNN: I think the quote is, “Dark and psychological.”

BOLLEN: Were you unnerved by some of the reactions or harsher criticisms to Gone Girl? For example, I remember being surprised by Mary Gaitskill’s critique in Bookforum, because, in my mind, she writes similar, often-unlikable, hard-to-pity characters. I thought she would have appreciated the Janus-faced madness of Amy.

FLYNN: I thought she would’ve, too. I love her stuff. If it had been just anyone, that review wouldn’t have bothered me, but… Well, my husband, who’s very protective of me, went through the house and removed all the Mary. He was like, “She will no longer be on our bookshelf.” [Laughs] But every critique that she had about the book, I thought, “That’s exactly what I was trying to do.” She didn’t like the world or the characters inhabiting that world, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not a good book. I’ll also say, any review that starts out with, “I don’t normally read books like this…”

BOLLEN: There’s still such snobbery about what literature can and can’t be, and what genres you are or aren’t allowed to access. That drives me crazy.

FLYNN: Maybe I was just sensitive.

But I also got that a lot from older, well-meaning gentlemen: “I don’t normally read books by women, but I read this and I thought it was really good.”

BOLLEN: Why do you think women tend to be such smarter and open-minded readers? Men don’t ever seem to want to move out of their preferred genre.

FLYNN: Because women are raised to be ambidextrous. We have to be able to think outside of our position or we’d never be able to get anything done in the world. We’re always reading and watching things made by men.

BOLLEN: Did men, by and large, have a different reaction to the book than women?

FLYNN: A large percentage of men really, really wanted Amy to die. Conversely, women tended to think Nick deserved everything he got.

BOLLEN: You ended up writing the script for Gone Girl. Starting with a script for a director like David Fincher really is like diving into the deep end.

FLYNN: I loved the process with Fincher so much. For me, there couldn’t have been a better way to start on screenwriting. From day one, he said, “Let the writer write.” So there was a pure level of comfort.

BOLLEN: I imagine it could have been the opposite, like a Kubrick take on Stephen King where the director wants to make the film version his and not the writer’s.

FLYNN: Fincher wasn’t like that. He really mentored me through the whole process.

BOLLEN: I loved the dialogue in your new film, Widows. That movie really captures the grit and beauty of Chicago. It’s so rare for a film to touch upon so many different worlds inside a single city.

FLYNN: God bless real places. So many films show the skyline of “Chicago” and then zoom in on a street and you think, “Nope, that’s Toronto.” Luckily, Steve [McQueen] had fallen in love with Chicago years ago when he’d visited for one of his art installations. So it was his idea to do it there.

BOLLEN: I didn’t know anything about its source, the 1980s BBC show Widows.

FLYNN: It’s pretty great. I’d never heard about it either. Of course I knew who Lynda La Plante was because she wrote Prime Suspect. But not Widows. I think it was a massive thing in the U.K. and Steve must have watched it as a kid.

BOLLEN: Like a Dynasty or Dallas for us.

FLYNN: Yeah, and I loved that Steve, after the success of 12 Years a Slave, wanted to go in a different direction. We could talk about so many interesting societal elements and wrap it in a badass heist film.

BOLLEN: It’s really a series of portraits of these very tough, complex women.

FLYNN: I deliberately put the women in different parts of Chicago. There’s that idea that you can live in a big city your whole life and still not meet anyone who’s not like you.

BOLLEN: There’s a huge twist midway through the film. I wonder, when you’re writing, do you ever get panicked that the twist won’t land? Or that the audience will see it coming?

FLYNN: I guess the answer is that you don’t know until it’s out in the world. For books, I always have my control group of friends who don’t know anything about what I’m writing. I depend on their responses. I had one friend who was reading Gone Girl and he went radio silent. I was like, “Oh, no.” All of a sudden, I heard from him: “Holy shit!”

BOLLEN: So, what is it about the Midwest that’s been such fertile ground for your stories?

FLYNN: Chicago is its own thing, but as far as Missouri and Kansas go, it does feel like a playground I largely have all to myself. Everyone thinks they know New York because everyone’s been there. But you can have a lot of fun with places no one has gone.