ICON

Founding Editor Gerard Malanga Takes Us Back to the Early Days of Interview

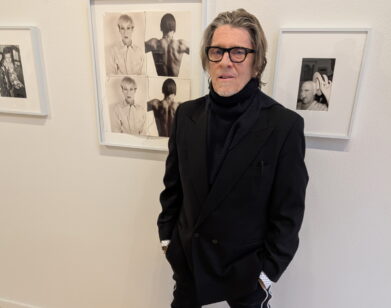

Gerard Malanga played a pivotal role in Andy Warhol’s creative output during the 1960s, serving as Warhol’s chief assistant from 1963 to 1970 and, alongside Paul Morrissey and John Wilcock, as an inaugural editor of this very magazine. Often described as Warhol’s most important collaborator, Malanga was integral to the production of his silkscreen paintings and multimedia projects, co-directing, editing, and starring in several of Warhol’s films, including the famed Screen Tests.

I first met Malanga in 2013 while curating 13 Most Wanted: Andy Warhol and the New York World’s Fair at the Queens Museum. Yet in many ways, he had been a presence in my life long before we were formally introduced. Like many of Warhol’s Superstars and Factory regulars—figures who initially existed to me as fleeting apparitions in films, or as fragmented traces within the Warhol archive—Malanga was a tangible presence well before our paths finally converged. Two decades ago, at the outset of my career as an assistant to the Chief Archivist at The Andy Warhol Museum, I spent my days immersed in Warhol’s vast personal archive, where Malanga was inescapable. His image materialized across countless reels of film, his name surfaced repeatedly in the meticulously cataloged inventories of Warhol’s Time Capsules, and his poetry appeared in delicate volumes interspersed among the artist’s own papers.

Since then, my work has remained deeply engaged with the world of the Factory. I have edited volumes on Billy Name, Bibbe Hansen, and Brigid Berlin, written extensively on Ray Johnson, curated exhibitions and contributed to numerous projects, always drawn back to the figures who first captured my imagination. Malanga and I are now friends, exchanging notes on literature between long hours in conversation over strong cappuccinos. What began as an archival fascination has transformed into something lived—one of those rare, full-circle moments in which the past folds seamlessly into the present and individuals who once seemed almost mythic become part of one’s daily life. This past December, in my role as Director of Galleries & Public Art at the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, I had the privilege of presenting the premiere of his newly restored films, an occasion that underscored the enduring resonance of his work and the ongoing dialogue between past and present.

———

ANASTASIA JAMES: So, let’s start at the beginning. You grew up in the Bronx, in a landscape punctuated by movie palaces, including the flagship Loew’s Theater chain. Since then, you’ve been a fan of cinema, not just as an art form but as an immersive experience. Can you reflect on how these early encounters with film and the cinema shaped your life?

GERARD MALANGA: Well, when I was growing up, I think I was maybe 11 at the time, I could go see movies by myself in any number of a half-dozen theaters. And there was one particular movie theater called The Valentine, which was part of a small chain by the Skouras Corporation. Spyros Skouras was at one point the president of 20th Century Fox. He was an emigrant from Greece who became a pioneer of the cinema. He also discovered Marilyn Monroe and had a somewhat paternal relationship with her. I loved going to The Valentine because I got to see foreign movies with the original soundtracks and subtitles. That’s how my education began, going to the movies at a very young age. And I also watched a weekly TV series called the Million Dollar Movie—that’s when I was introduced to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, which aired seven nights in a row, and I watched it all seven nights.

JAMES: Was that one of those defining moments of your childhood?

MALANGA: It was, in a way. I was very excited to see a movie like that. I didn’t really know what I was seeing, but I was fully absorbed with whatever was going on on the TV screen.

JAMES: You’ve talked to me before about the influence of formative mentors in your youth. Someone who’s come up a lot is Daisy Aldan.

MALANGA: Well, Daisy was a respected poet in her own right, and she was a high school English teacher in my senior year class. Everything in my life at that time, even now for that matter, seemed to be by chance. I had signed up in my junior year for the next year’s classes not knowing who my English teacher was going to be. I could have gotten any one of a half-dozen English teachers at that time, but I ended up in Daisy’s class and she basically changed my life. Within a week or two of being in Daisy’s class, I was completely mesmerized by what she was teaching us. In her class, I learned about Dada and Surrealism and Stéphane Mallarmé, and she even brought in Anais Nin as a speaker. I moved my desk from the back of the classroom to the front seat near her desk to fully absorb her presence. She was so magnetic.

Gerard Malanga, age 12, in front of the poster display at the Valentine Theatre in the Bronx. Photo by Gerard’s father, Gerardo Malanga, 1955 © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

JAMES: Another person you speak very fondly of is the filmmaker Marie Menken who, despite her undeniable contributions to culture, remains largely unknown outside of avant-garde film circles. Yet, from your first encounter with her she became a significant person in your life.

MALANGA: When I met Marie Menken, she was married to Willard Maas who was my English teacher at Wagner College. He was also a poet and filmmaker. Marie was quite an amazing force in my life. Not only from the point of view of her being so talented; she was a creative multi-tasker. She started out as a painter, showing with the Martha Graham Gallery. At some point in the late 1940s, she picked up the camera and started shooting movies and fell in love with the medium. She passed that love of making movies and her knowledge over to me during an impressionable period in my life. I was very fortunate to have met her. Marie had it; she attracted people. And I designed some titles for a couple of her movies.

JAMES: She used to loan her 16mm Bolex movie camera in the early-to-mid 1960s, and then in 1968 she gave you your first 8mm movie camera.

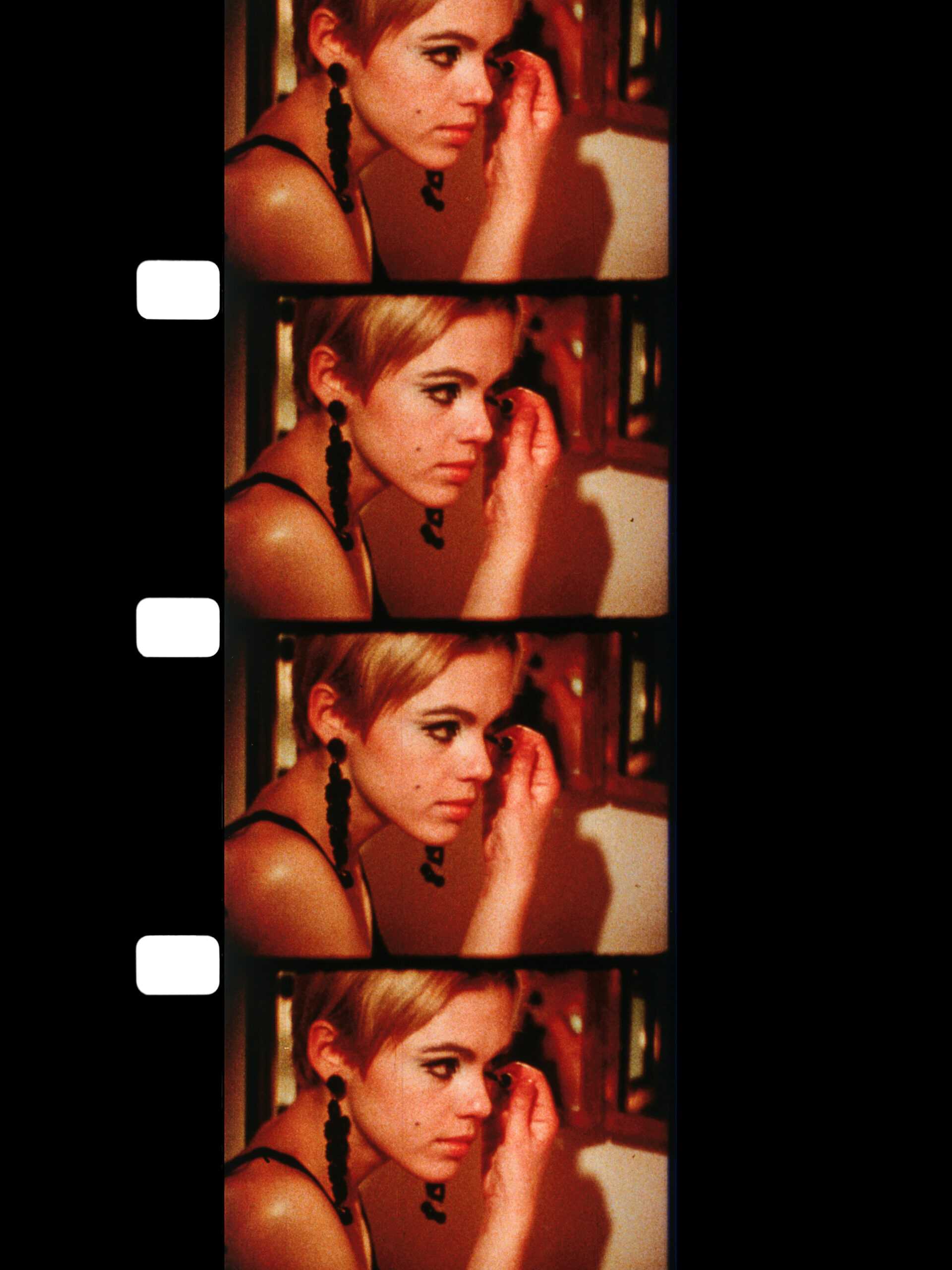

MALANGA: It was a Keystone. I have a duplicate of that camera in my archive upstairs. It was just a very easygoing 8mm movie camera. I had just returned from Italy and didn’t have a camera of my own. I was working with a borrowed Bolex, which I had recently returned, so I had nothing to shoot with. Marie said, “Here, take this. Go out and shoot a movie!” She was very aggressive, Marie. She could bellow out commands. So I shot this movie over a period of a few weeks in the summer of 1968 and it turned out really well. That film became The Filmmaker Records a Portion of His Life in the Month of August 1968, which was recently restored to 4K. It was basically a filmic diary of my life that month, capturing brief moments with just about everyone I came into contact with in New York City and the Hamptons: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Sterling and Martha Morrison, Paul Morrissey, Joe Dallesandro, Piero Heliczer, Ron Zimardi, Andy [Warhol]. There are a lot of cameos in that one.

JAMES: That’s fascinating. And you prefer to call them movies and not films. Why is that?

MALANGA: Well, I like the word movie. It was the word that I grew up with. I would go to the movies. I didn’t go to films, you see? It was kind of a linguistic situation. But I like the word movie because it has a lively ring to it.

JAMES: Maybe a little bit more playful.

MALANGA: Playful, yeah.

JAMES: Well, your personal archive of experimental films, the so-called “secret cinema,” presents an alternative history, avant-garde cinema during the 1960s. What do you hope that people take away from your Secret Cinema book?

MALANGA: Well, the only thing that I can think of really is that if someone is interested in making a movie, the book might say something to the effect of, “Even you can make a movie,” you see? I felt there was a kind of universal thing to the way the book was put together. This book was a long time in the making.

JAMES: How did this book come about?

MALANGA: Well, Secret Cinema was a project that I started with my friend, publisher Dagon James, back around 2012, I think. He became interested in my movies after putting together a feature about them in his magazine Lid. At that point, I wasn’t sure we could get this book together because most of my movies were scattered and some forgotten. Dagon was tenacious and spent more than a decade tracking down prints and stills. It was a process with a lot of stops and starts, but it finally came together. It doesn’t have every movie I ever made, but it’s as close to complete as we’re likely to get.

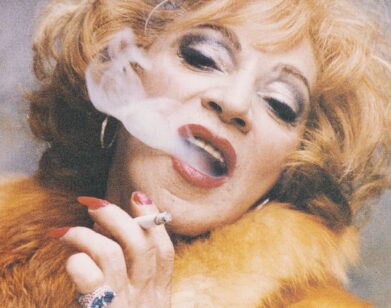

Jane Fonda, Candy Darling and Andy Warhol aboard the SS France, 1969 © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

JAMES: What was it like revisiting what was essentially a lost body of work going back more than 60 years?

MALANGA: It turned out to be more enjoyable than I expected. I’m not a nostalgic person, but revisiting these old movies was like seeing old friends, which brought back a lot of fond memories. It’s a part of my life that was kind of pushed to the side. I’m happy with how Secret Cinema turned out and, for a lot of people, it kind of fleshes out the story of my life during the 1960s through the lens of my movie camera.

JAMES: Let’s talk about some of those movies before we jump into your engagement with Warhol’s filmmaking. I think one of the films that a lot of viewers were drawn to when we screened the films in Pittsburgh was Andy Warhol, Portraits of the Artist as a Young Man. Can you tell me about that film?

MALANGA: Well, I was collaborating with Andy on the Screen Tests and I thought it would be nice to do something with Andy as the subject in a similar style. So that’s how that film evolved, basically. I shot seven three-minute reels over a period of several months between 1964 and 1965, and it’s a human visual record of who Andy may have looked like at that time when we were still screening. I combined all seven reels, out of sequence from how I shot them, into a single 21-minute movie.

JAMES: What do you see in the portraits that others might miss?

MALANGA: Perhaps what I see in the portraits is maybe a kind of vulnerability, who Andy was at that time that he would allow himself to sit and be filmed the way we were doing it with other people. Andy never shot a Screen Test of himself, so this movie kind of fills in that blank space in the Screen Tests series. Also, it’s important to note that the Screen Tests we were shooting at the time were typically static; I utilized a lot of stop motion edits in the camera and experimented with the lighting, so it visually stands on its own.

JAMES: I’d also like to talk about what is called Gerard Malanga Film Notebooks 1964 to 1970, which are some of my favorite films in your body of work. Why are they called notebooks? And how do they relate to your writing process?

MALANGA: I call them notebooks because there’s basically no formal, physical structure to the films. To me, they had the feeling of being notebooks, visual notebooks. So that was something that I immersed myself in, that physical aspect of making those movies. It’s kind of a diaristic collage of interesting meetings and moments during that time in my life where I took what are mostly individual three-minute reels and stitched them together. It opens with Bob Dylan and I at the Factory and transitions to moments through the rest of the decade with Donovan, Edie Sedgwick, Salvador Dali, the Velvet Underground, Cecil Beaton, and it ends in 1969 with Charles Olson at home in Gloucester. I mean, there’s a lot of visual footage that still hasn’t been utilized yet. Actually, I’ll probably look at another film or something.

JAMES: Your film notebooks, and all of your films in general, remind me that one of your most overlooked yet significant contributions to the 20th century is your role as a connector. You introduced individuals to people, to each other, and their encounters sparked countless creative chain reactions that shaped the trajectory of art history. Secret Cinema includes a wonderful essay by John Wieners in which he recalls the moment you introduced him to Warhol. Looking back, do you see this ability to bring people together as an extension of your artistic practice?

MALANGA: Well, to me it all seems obvious that by introducing someone to someone else, something interesting might happen. It was a very natural thing to do. I seemed to be meeting people on my own anyway, so it was never really planned in any formal way. It was a very informal intimacy that seemed to gravitate one person to another person.

JAMES: It kind of lines up with a quote in the book where you say, “In 1963 I began working for Andy Warhol. It wasn’t a big deal to me at the time. It was supposed to be a summer job. My plan was to return to school after the summer, but plans have a way of changing.” I think it’s one of the greatest quotes that you have ever put down on paper. How it was that you came to The Factory?

MALANGA: Well, this was in 1960. I was basically looking for a summer job because I had to go back to school. At some point. I was actually a student of Willard Maas’s at Wagner College. And this was just after I graduated high school.

JAMES: How old were you?

MALANGA: I was still 17 at the time. So Daisy introduced me to a former student of hers. I was class of 1960, and Leon Hecht was class of 1952, let’s say. So Leon was a very successful textile designer. In the field, he was considered one of the best. Daisy introduced me to Leon Hecht and he hired me for a summer job. And that’s where I learned how to silk screen, and in fact I had a lot of fun doing it. When I was working for Andy, at the beginning, Andy said he had a number of people who came to work for him, but nobody stayed at the end. I asked, “Why was that?” And he said, “Well, people would find silk screening to be a very boring occupation.” But I didn’t find it boring at all. I found it quite fascinating and enjoyable.

JAMES: And I think that’s something that a lot of people don’t realize, which is that you were hired by Warhol because of your technical skills.

MALANGA: Yeah, that’s true. The timing was quite interesting in terms of how that all came together. So I was well prepared to engage in a situation with Andy that I basically didn’t know where it was going to go. In fact, it was at that point that I decided I’d rather not go back to school in September because I’ll stay with Andy and I’ll take that road trip with him to California, which is a whole other story.

Gerard Malanga & Andy Warhol filming Couch starring Ivy Nicholson & John Palmer, the Factory, 1964 © Gerard Malanga. Courtesy The Waverly Press.

JAMES: Let’s talk about the Screen Tests. A few days ago, you and I were talking about the very first film portrait that Warhol created of you. Can you tell us a little bit about that portrait?

MALANGA: Well, the film portrait was something that I had an idea about because I needed a photograph that I could use in the future to promote my poetry readings. It would have been a publicity photo. I was always fascinated with the way movies were sometimes reproduced in film magazines, particularly films by Stan Brakhage. So I set up the camera, this was around November of 1963, and I designed the whole lighting situation around this particular three-minute movie. And it turned out really well, actually. So I suggested to Andy, “You know, you should just do more of these film portraits.” At the time they weren’t called Screen Tests, they were called “film portraits.” That’s how the Screen Test series started. It was with the knowledge I had acquired from experimenting with that first footage. That first reel that we shot looks kind of different from the later Screen Tests.

JAMES: So if that was made in November, when was the first Screen Test made?

MALANGA: I think there was a group of us at a party, a daytime party, in early January or February of 1964, and there was a Screen Test shot of me during that period. But I didn’t like that portrait very much. I think I was wearing a white shirt with a tie, but it just didn’t grab me. But from that point on, we were shooting a lot of Screen Tests because Andy had just found a space where he could work on the paintings, which I think was a former hat factory, and that space became known as the Silver Factory. So we continued the series of Screen Tests in that space, which is where most of the 500 or so Screen Tests were made.

JAMES: And to be clear, those first early efforts were done at The Firehouse Studio.

MALANGA: Yeah, mine was filmed on the first floor at The Firehouse because only the ground floor had electricity. The second floor was where we silk screened paintings in the daylight by the windows looking out over the street.

JAMES: And the Screen Tests continued through January 1967, concluding, I believe, with the Screen Test of Allen Midgette.

MALANGA: Yeah, Allen Midgette was the last Screen Test that we shot for the book Screen Tests/A Diary that came out a few months later.

JAMES: One thing I wanted to ask you. I bet most of the readers of Interview aren’t aware of this particularly obscure chapter of Warhol history, which was from June 25th through August 5th, 1969, when Warhol rented a theater called the Fortune Theater in the East Village, rechristening it Andy Warhol’s Boys to Adore Galore, where silent pornographic films played in an unbroken loop. Somehow you found yourself at the helm of this enterprise, managing what became known, in places like The Village Voice, as Gerard Malanga’s Male Movie Mag. You told me that you hired Jim Carroll in the box office and Joe Dallesandro as the projectionist.

MALANGA: It was another way of earning some loose change, you know?

JAMES: Did it actually generate revenue?

MALANGA: It would have, but the police department got wind of this and actually ended up busting another similar theater in the neighborhood down the block from where I used to live on 14th Street. When they got busted, we decided that we better close shop or we’re gonna get busted too, so that’s what happened.

JAMES: And how did you feel about managing the theater?

MALANGA: Well, it seemed like a fun thing to do. At that time, I wasn’t officially working for Andy until the following September. I had just gotten back from Rome, so I was in need of work. I was approached by Paul Morrissey to be front for the theater, because Andy didn’t want to have his name attached to it, so I volunteered to manage that project. Jim Carroll, many years later, admitted to me that he was taking some of the money from the box office receipts to buy drugs. All I could do was laugh at that, you know?

JAMES: And since we’re doing this interview for Interview, it feels appropriate to ask you about your role in the founding of Interview magazine.

MALANGA: Well, what happened was Andy was approached—or, rather, I should say Andy approached the New York Film Festival for press passes and he was turned down. So part of the reason why we started the magazine was to have an official way of getting the press passes. So Interview was started partly on the basis of that particular situation. The name Interview is a slash—it was Inter/View, and the “view” part an homage to Charles Henri Ford, who was the publisher of the very, very influential and fantastic arts magazine called View Magazine back in the late 1940s. So one thing leads to another, you know, and we did get the press passes, and John Wilcock was certainly an incredible factor in the founding of the magazine, because he had all the right connections between the press passes, the printers, and the distribution. It was not that expensive to put together a magazine like that. They were basically a newspaper.

JAMES: So what was the first issue like? Do you remember what you printed or what you wrote?

MALANGA: The first issue had a movie still, a publicity movie still for Agnes Varda’s movie. I forget the name of that movie. I think it was a movie she shot in New York. So we were promoting Agnes Varda and that was the cover story. And the second issue, we were doing a cover story on performance. I don’t think I was the director of performances. Again, my mind is a sieve.

JAMES: How many issues did you work on?

MALANGA: I worked on four issues.

JAMES: And what happened when you left the magazine?

MALANGA: Well, nothing happened when I left. It still went on doing what it was doing, working for Andy until November of 1970 when I basically left The Factory altogether.

JAMES: This morning you mentioned that you were still an avid reader of Interview and that you were quite happy with how it seems to be returning to its roots. Could you elaborate on that?

MALANGA: Well, a little bit. I mean, I was not an avid reader of Interview. But the last couple of issues, I liked what was happening with the magazine with all the fashion ads and the color photography. It reminded me of what the issues of Interview were back in the early 1970s.