Geoff Dyer, Journey Man

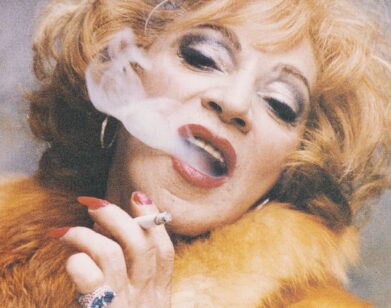

ABOVE: GEOFF DYER. PHOTO COURTESY OF MATT SUTART

Who wouldn’t like to partake in a journey leading to a room in which your deepest desire comes true? This conceit makes up the central premise of Andrei Tarkovsky’s influential 1979 science-fiction film Stalker—which has inspired a new book, Geoff Dyer’s Zona. With Zona, Dyer—well-known for his imaginative approach to his subjects—again evades the conventional shackles of genre by blurring the lines between form, style, and plot. What starts out as a rather painful shot-for-shot retelling of a decades-old film (which wasn’t brief to begin with) surprisingly manages to go above and beyond its source material, ending up a surprising and very literary work.

Dyer, who based the book on a movie about a journey, molds this idea into the central theme of his newest work, taking the reader on a “journey” through his mind, his past, and, ultimately, what it means to be human. We caught up with him shortly before the book’s release.

LUCAS BSCHER: If somebody hasn’t seen Stalker, do you think they should wait and read your book first? Or vice versa?

DYER: [laughs] Yeah, I mean, perhaps the only thing, really, that this sort of crazy and in many ways entirely un-commercial project has going for it is that it’s not essential to have seen the film before reading the book, which is really quite unusual when you think of a very detailed sort of study of a book.

BSCHER: Of any work, really.

DYER: [laughs] Yeah. So it’s not essential—but I think there is no doubt at all that you would probably get more out of the book if you have seen the film.

BSCHER: While I was reading your book, Flaubert came to mind, and then you actually mention him—citing the letter from the 19th century in which Flaubert introduces this idea of the book about nothing.

DYER: Oh, yeah.

BSCHER: One that is supported by its own style, rather than a forced narrative—which reminds me of this book, where the narrative is, if anything, just driven by the film. Were you influenced by Flaubert?

DYER: No. Not influenced by him—but certainly, the thing about the film is, although it has got a narrative that can be summarized very, very easily, it does have a sort of have quite a considerable narrative propulsion, because it’s a journey. And any kind of book or film or quote that has a journey in it is inherently kind of absorbing. So all I had to do really was, as we say, to hitch my car to the film’s pony. I just went along for the ride, as I maybe say at one point. And although Flaubert has not been any kind of influence on me, at all, really, that letter has always stood out to me as an incredibly important moment in…

BSCHER: Literary history?

DYER: Yeah, exactly. Even by today’s standards, let alone the time it was written, it’s incredibly forward-looking. And much of the fiction that I most like is maybe not about nothing, but it does sort of set the bar higher rather than lowering it.

BSCHER: Just a moment ago you mentioned the journey. The film is quite ambiguous about the fact whether its central journey ever really takes place, or whether it’s imagined—in which case, the entire film might be interpreted as an inner journey. Do you think happiness can really be found through an inner journey? Even if our circumstances, mood, and belief systems can so easily be affected by the external? Or do these things simply redirect the journey?

DYER: Well, all the evidence is in, really, to suggest that one’s happiness is very largely a question of state of mind rather than the world you are looking at. Although of course certain views of the world are more conducive to a content and happy state than others. In terms of The Zone, yes, you are absolutely right [about] the way that the film is set up, the way that this journey begins and ends, with this bar, and there is no accounting at all in the film of their journey back. One minute they are sitting there on the threshold of the room, and the next we cut right back to where we started. So it certainly raises that possibility. And even if we accept that on the most literal level they have gone somewhere, it’s still by no means guaranteed that the place to which they have gone really has the magical powers, which it is alleged to have. It is quite possible that any magical powers it had were only the product of their believing that it does.

BSCHER: In the book, you mention that one of the novelties of our era is the sense of “instant boredom.” Is that a sort of central theme of your life—that accounts for the wide range of topics you choose to work on and this genre-defying style that so uniquely pertains to you?

DYER: Yeah. I think I do have a sort of terrible propensity for boredom and for being bored, even though I am absolutely of the opinion that one shouldn’t be bored and that there is no excuse for it and that it is a personal failing. But I guess that as life is speeded up and our capacity for concentration is being nibbled away at by all the obvious things, that leads us actually to be more susceptible to boredom. And I guess one of the things that the book is addressing is that when I was in my early 20s, I was so geared up to be able to concentrate on films like this. It was all my prior experience of cinema had led me to believe that these great works of art probably are not going to reveal themselves as readily and instantly as a pop song might. And I really wonder now if somebody going to see—when I saw it at the time, it seemed pretty slow, but I was able to sit through it—but it seems to me that Stalker and Tarkovsky films generally and films like that must seem even slower now then they did back then, because everything has sped up so much more.

BSCHER: Is there anything else you would like to add?

DYER: No, I guess the only thing I would stress, and I stress this because it’s something I only realized after I had finished the book, which is that for me, although this obviously is a book about a movie, I realize now that it is part of a biding interest I have had with places where time has stood its ground. And you know, one of the striking things about the Zone in this film is that there is no time there. And as I look back at some of the other books I have written, I realize that this is a sort of long-running area of interest and I’m always drawn to these kind of pilgrimage sites. Not necessarily traditionally religious ones, but in fact particularly places that people can go to in a kind of non-religious way. So I think about that thing I wrote about Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field in The New Yorker. I mean a really deeply powerful place, but not one that is, that is…

BSCHER: Not vulnerable to time, in a way?

DYER: Yeah that’s right. Certainly built to last.

GEOFF DYER’S ZONA IS OUT NOW.