IN CONVERSATION

Gayle Rankin Tells Michaela Coel How She Made Sally Bowles Her Own

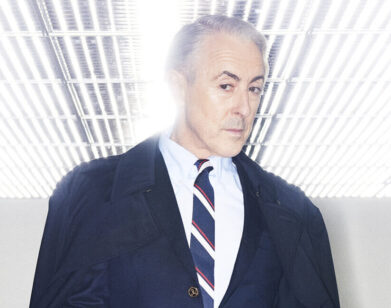

Gayle Rankin, photographed by Emilio Madrid.

Every night, before she transforms into Sally Bowles in the new Broadway revival of Cabaret, Gayle Rankin reads the Emily Dickinson poem “Hope is the thing with feathers.” The routine, she told the writer and actor Michaela Coel last week, has as much to do with cultivating a sense of ritual as it does tapping into something fundamental about the iconic character for which Liza Minnelli won an Oscar in 1973. “It’s a horrendous story about fucking fascism and the end of the world and people breaking under extraordinary pressure,” says Rankin, whose tenacious and raw interpretation of the role—in the first-ever production of Cabaret directed by a woman, Rebecca Frecknall—has earned both her and co-star Eddie Redmayne Tony nominations. “But what I find so fucking luminous about her,” Rankin continues, “is that there is hope.” While Coel made her way to dinner at the White House, she called up the 34-year-old Scottish actor to talk about bringing Sally Bowles to life and finding peace in an unlikely place: Upstate New York.

———

GAYLE RANKIN: How are you doing? Are you on a train, babe?

MICHAELA COEL: I’m on the train. I changed the time so that I wouldn’t be on the train, and then the train got delayed, so here I am.

RANKIN: Good. Did you just have dinner with the President of the United States?

COEL: I’m on the way now.

RANKIN: Fuck. Oh, fuck.

COEL: Yeah. To be fair, I’m somebody’s plus-one.

RANKIN: Little do they know, but–

COEL: Exactly, I’m going to be the life of the party.

RANKIN: Precisely.

COEL: Gayle, I’m sure you’ve heard this loads of times, but thank you so much for your work on Cabaret. I was stunned. I had never seen you before and I was like, “Who and what the fuck is that?”

RANKIN: Thank you. That means the world coming from you because I’m such a huge fucking fan. I’m a dear friend of Paapa [Essiedu]’s as well, so I feel like we met a long time ago.

COEL: I know. Actually I think you’re the only person I didn’t get to meet after the show.

RANKIN: Oh yeah, you came.

COEL: Yeah. I’d also been in London before to the previous iteration of the show. Were you familiar with that version?

RANKIN: Well, I had just shot a movie with Jessie [Buckley] and Paapa, and Jessie was about to go into rehearsal for [Cabaret]. I had plans to go and see it, and something changed with my trip and I never got to go. And when it ended up that I was going to be in it they were like, “Do you want to come and see it?” And I was like, “You know what? With the biggest amount of respect, no.” Because I had been in Sam Mendes’ production 10 years ago, so I had an epic history with the material and I needed to process. I needed to have as much of a clean slate as I could.

COEL: Yeah. Very good, very good.

RANKIN: And trying to play Sally Bowles… Everybody has enough opinions about it anyway; about what she is, who she is, what’s going on. I needed to be able to formulate something with my relationship with the text alone. I was always very aware of the production, how incredible and innovative it was. And the fact that it was the first time a woman was directing Cabaret. It’s shocking that it’s taken this long, and Rebecca [Frecknall] is such a visionary.

COEL: You know, it’s amazing how producers and writers can have an idea of a character, and if you don’t put restraints on an actor, they can show you something that your mind would never have conceived. That’s why I’m so glad that you didn’t see the previous version, which is obviously fantastic, but this was so different. So I wonder, who is Sally Bowles to you?

RANKIN: What got me about Sally is that everybody thinks they know who she is. Everybody has a really strong opinion about the decisions she makes, the way she is, the way she isn’t. It brings out a strong reaction in people. I find that fascinating, especially directed at a young woman or a woman in her prime, the fact that her identity can be co-opted. I found a real injustice in that, and I wanted to take that on. People think they own her. She’s become a mysterious icon and not a person. She hasn’t been allowed the space to have her own identity. So I had to get in there, and it sounds really cheesy and maybe a bit wonky, but I was like, “I had to just listen.” I wanted to listen to her because I was like, “She’s got something to tell me, to tell us, that we’re not hearing.” My investigation was so much about listening and trying to get out of the way, because she’s smarter than a lot of people assume.

COEL: Yes. That’s what I got from you. There was something very earthy. It was going down into the earth and it felt low and heavy and deep, and it shocked me. How do you do it every night? Sometimes twice a day. The longest one I’ve done is four weeks.

RANKIN: God bless. Four weeks?

COEL: Four weeks. And I did it once. How do you do it and keep doing it?

RANKIN: I’ll say that I have a difficult time, as many artists do, staying present. And who wants to be in the present? We live in this world and it can be beautiful and totally horrendous. But this show attached me to the present in a way that I haven’t ever been, ever in my life, ever. I feel very alive because I’m using my body and my nervous system and my voice and my morality in a way that I’ve never had to before. And I have to check in with it every fucking day. It’s a very active and alive thing, so I feel grateful for that. Also just audiences. People coming, getting to talk to you, to other artists about what we’re doing and why. It’s just forgetting about it and being like, “I can fucking do this.”

COEL: So in a way, it’s like anchoring in the ritual of it.

RANKIN: Mm-hmm.

COEL: I can understand that. I read you went to Juilliard, did you leave in 2011 or you went in 2011?

RANKIN: I graduated in 2011, yeah.

COEL: And have you been in New York ever since?

RANKIN: Yeah.

COEL: You’ve probably been asked this loads but, do you find any threads between you and Sally because of that?

RANKIN: It’s funny, actually no one’s asked me that, but of course you’ve asked me. That’s so beautiful, thank you for seeing it. I think there is a displaced, artist-type person who’s trying to find their place and I absolutely see it in her. What’s also interesting about why I wanted to take her on too is, there’s all this chat that’s almost 50 or 60 years old about how bad or mediocre she is as an artist. There’s this conversation around how good or not good, and it’s like, “Are you going to do the version of Sally that’s good or not good?” And I’m like, “What is that discussion and where does that come from, because it’s not in the text.” There’s not one mention of her being mediocre, ever. And I’m not saying that Sally Bowles has to be or is an amazing artist, but she’s an artist. She has the soul of an artist, a creative. I was deeply adamant that that was going to be real and alive.

COEL: Well, I definitely felt that. Maybe because your voice has got some musk to it, and it felt modern. It felt like you were being you and also being Sally.

RANKIN: Yeah, it was like a dance.

COEL: It was really cool. And sometimes you were singing, but you were half-talking, like it came out and it happened to be a song, but it wasn’t even intentional at times. Mind-blowing. So you’ve been in America for 13 years having left Glasgow, right?

RANKIN: Mm-hmm. It was a big fucking jump.

COEL: What do you do outside of performance?

RANKIN: If I’m not performing, I’m not actually working on set or doing a play or a musical, I’m developing stuff with people or working on my own stuff. But I love to cook and I love to travel. I love to be upstate. Do you live in New York?

COEL: I’ve been here for seven months now. One thing I love about America is that you don’t have to go far to feel like you’re in a totally different country. The landscapes are so varying. I write upstate. I like Storm King.

RANKIN: Love. You’ve been to Woodstock?

COEL: No, actually.

RANKIN: Oh, that’s pretty fucking great. I’ve just started going to Hudson because I’ve got friends up there and we started to look for houses, because I love being in the country. It just reminds me of home and stuff like that. But it’s an interesting thing from the UK–

COEL: How so?

RANKIN: Well, I started to think about it, why did I choose America? I just started working more in the UK again, so I was spending more time there. And I don’t actually know if there’s a better place to be as a human being nowadays. But I don’t know, I do like it here. Maybe it’s because of escapism. I wanted to escape and I did.

COEL: Maybe there’s something about daring to move, especially at the age you were, that enabled you to be who you want to be maybe more so than if you’re in Glasgow. To discover all the different possibilities of who you might be. That was for my mom. My mom immigrated from Ghana to the UK. She was curious and that’s why she left. She wanted to know how other people live, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, you know?

RANKIN: Yeah, there’s a grief in it too, right? That’s also maybe what we try to explore as artists.

COEL: I was really curious about this, I know you are doing the next House of the Dragon, and I read a quote from you that said you previously have subconsciously chosen roles that enabled you to maintain your sense of anonymity in the world. Is that something that’s changing now?

RANKIN: Mm-hmm.

COEL: I know that feeling. What is important for you to hold onto as your surroundings and opportunities and perspective broadened?

RANKIN: My work ethic, my artistic voice. Because my voice, I hope, actually strengthens my voice as a person in the world. I hope my artistic voice remains loud and clear inside of my own body. I’ve been listening to it because that voice can leave the body and then it belongs to somebody else. I hope that remains in place. And my friends are just everything to me. They’re my family. Keeping them as close as I can.

COEL: I feel compelled to tell you, if you ever get lost, you can always find your way back. Sometimes, I feel like performers, we end up in a job and actually it was a mistake and we’re mad. It’s about having compassion for ourselves and knowing that it’s okay. There is something that benefits us in everything and you will find your way back.

RANKIN: Thank you. That’s so generous, because you look at other artists that you fucking respect so much and you’re like, “Wow, your voice is fucking razor sharp. But I also know that you’re a human being and for all amazing artists and voices, there is challenge.” Part of that challenge is being met by something that doesn’t always exactly fit and you have to find your way through it. It’s heartening to feel honesty about that.

COEL: Yeah, it is a part of it, and to know your true voice and your true instincts and your identity as an artist. For me, I’ve really had to understand what it is to betray it, to go through that and then be overwhelmed with gratitude and humility when that voice that we listen to speaks to me again. It’s so understanding and forgiving and learning how to open ourselves back up when we get a bit clogged to receive that voice and be in communion with it once again. It’s a beautiful journey, isn’t it? The ups and downs of it.

RANKIN: Totally. I’ve felt it inside of this show. I’ve had so much doubt, so much judgment of myself. And to return back to something soft is humbling. There’s a poem that I read every single night before I go on stage. It’s an Emily Dickinson poem, randomly. It’s called “’Hope’ is the thing with feathers.” I started to have this really funny relationship with the word “hope” and the word “maybe” because I was working on the song, “Maybe This Time.” And the idea of maybe and hope being flimsy. I was really fucking judgmental about that softness rather than the idea of faith. But the truth is, the truth is all hope. What is beautiful about Sally and about my job at the moment is to be somewhere right in the fucking hot, soft center, and trust that. And it is uncomfortable.

COEL: Yeah. It’s funny you say that. I went through a similar thing with the word hope a year-and-a-half ago and I actually got really frustrated with a friend of mine who was talking about hope. I was deconstructing the word, like, “What is it? This is bullshit.”

RANKIN: Yeah, yeah. It’s so interesting. I also think what’s so interesting about Sally, last thing I’ll say, is that there’s hope. It’s a horrendous story about fucking fascism and the end of the world and people breaking under extraordinary pressure. What I find so fucking luminous about her is that there is hope. There’s something bright and brave about someone saying, “I’m going to lift this ceiling, this veil, off of my head and see how that feels. And I’m going to die like everybody else. But what would my life be like if I could feel that? How could I show up for other people?” Anyway, I could go on for fucking ever.

COEL: That was so nice. It was lovely to talk with you.

RANKIN: So nice. Thank you for doing this. I really appreciate it.

COEL: Thank you for moving me so much with your performance. I hope to come back and see it again.