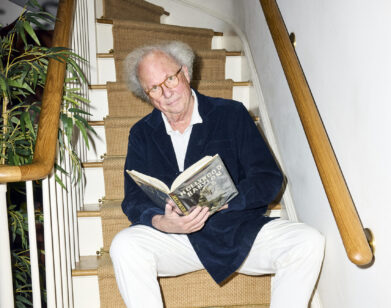

Gary Shteyngart

In a way, the memoir feels like giving away the story, the story behind the story. This is where it all came from. Gary Shteyngart

Let the Russians have their Gogol, their Turgenev! Let Putin stay home and read Dostoyevsky! We lucky—knock on wood—Americans have tricked the Russkis into sending us Gary Shteyngart, their greatest export since they rocketed Laika and all those other cute little dogs into outer space for the Soviet cosmonaut program.

Since his first novel, The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, appeared in 2002, Gary Shteyngart has introduced us to a whole new literary genre: The wildly inventive comedy of Russian-American immigration? I suppose you could call it that. Or, a Gary Shteyngart novel? Definitely.

Shteyngart’s second novel, 2006’s Absurdistan, tracked the misadventures of Misha Vainberg, the 325-pound son of a Russian gangster oligarch. His brilliant third book, 2010’s Super Sad True Love Story, set in a dystopian, Orwellian future, brought us into the simultaneously hilarious and tragic world of Lenny Abramov, who works for an Indefinite Life Extension company and is madly in love with Eunice Park, a much younger Korean-American woman.

In his astonishing and dazzlingly honest new memoir, Little Failure, which some have already called his best book yet, Shteyngart has taken off the masks that have made his fiction so (relatively) enjoyable for him to write. Little Failure—as Shteyngart’s mother used to call him—begins in Soviet-era Leningrad, where Gary (or Igor, as he was named) was born in 1972 and lived with his complicated, tough, overburdened parents. As funny and sad as (well, actually, more sad than) his novels, the memoir follows Shteyngart to Vienna, to Rome, to a hellish Hebrew school in Queens, to Stuyvesant High School, Oberlin College, back to New York—and ends more or less at the dawn of his literary success.

Three days after the birth of his first son, Johnny Won Shteyngart, Gary and I met at a restaurant in SoHo to eat oysters, drink booze, and talk about why bleeding onto the page—even a highly controlled and immensely artful bleed like Little Failure—is a lot more difficult than inventing a fictional world and populating it with imaginary people.

GARY SHTEYNGART: Should we have something to drink to lubricate our …

FRANCINE PROSE: Oh, yes. I want some weird mixologist cocktail.

SHTEYNGART: Let’s get tons of oysters. I just swam a mile.

PROSE: You just swam a mile? I just ate lunch for the sixth time. Okay, I want to make sure the tape recorder is running before I start emoting about your book.

SHTEYNGART: I think it’s okay.

PROSE: Gary, I loved the book so much. Since I read it, I think I’ve had maybe six conversations with other people, and I’ve told every one of them that they had to read it. Immediately! I couldn’t put it down. I read it the whole time I was having my hair cut. When I was getting my teeth cleaned, I was trying to figure out if I could somehow hold the book and read without getting in the hygienist’s way.

SHTEYNGART: It’s as painful as a tooth cleaning.

PROSE: It’s intense and very funny. But so sad, Gary …

SHTEYNGART: It’s the legacy. That Russian, Ashkenazi Jew thing: Oh god, life sucks, yet it’s kind of funny.

PROSE: I know, but the book is sad in a way that goes beyond the Russian stuff. You capture that hopeless love affair we have with our parents and that hopeless love affair they have with us.

SHTEYNGART: Yes, hopeless, I think, is a good adjective.

PROSE: Hopeless is the best-case scenario.

SHTEYNGART: Hopeless is the best-case scenario.

PROSE: And it reads like a Russian novel. It’s wrenching in that same way.

SHTEYNGART: I tried to set up an arc, but I don’t know … As they say in the industry, I had third-act problems.

PROSE: But it doesn’t feel managed or artificially arranged. It seems—excuse the word—organic. Plus it’s one of those books that make you think, “Oh, I should have talked to my relatives more. I wonder who’s still alive, who I can call up and ask about our history and where I come from.”

SHTEYNGART: It required that. The research for this was insane. My parents were kind enough to spend hours talking to me. They also like to talk and give their own version of things, obviously. And they went to Russia with me, which was the most painful part of all. I was just shocked. It was so concentrated. It was an affirmation of the past—my past and the past of the country. All of it. I did research, but I have a great memory. And actually, I remember Russia in some ways better than I remember Queens. Since 1999, I’ve gone back to Russia almost every year. Although after this book, I don’t think I have to so much. For a while anyway. And my friends were really helpful. Jonathan from Hebrew school! Plus a bunch of people I hadn’t seen since Stuyvesant. In writing these stories, I kept asking myself, “Did this happen,” or “Is this the way the story was formed?” This isn’t a work of journalism, but I backed away from a couple of stories that felt to me, like, “Well, I don’t know, this could be hearsay.”

PROSE: Like what?

SHTEYNGART: Well, there’s my aunt’s endless quest to prove that we are descended from “Prince Suitcase” [who, according to Shteyngart’s aunt, was “one of old Russia’s illustrious figures”]. That could’ve been an entire chapter in and of itself. But I tried to do some due diligence, and it wasn’t really what I wanted to write about, so I didn’t, for the most part. I have some memories of certain things that happened in high school when I was stoned out of my mind, but I talked with other people about them, and I trusted the aggregated memories. Because when you’re stoned out of your mind, you don’t really know what’s happening. I tried as hard as possible to make this as truthful as possible.

PROSE: It feels that way. It’s so un-self-protective and so raw. Ever since I read it, I feel like in some ways I know you better than I know my husband—and we’ve been married 40 years. Remember when we were all hanging out in Rome? Somehow I just didn’t realize what it meant that you’d been there before. I sort of knew, but there was no way I could understand the difference between the crummy apartment in Ostia, where you lived with your parents en route from the Soviet Union, and that beautiful apartment that belonged to some relative of the baroness, where you were staying over the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele.

SHTEYNGART: Yeah, it was very intense. But the memoirs I love are all very intense. If you’re going to do a memoir and protect yourself, what the hell’s the point? Just do fiction. So I took a risk. And I know it’s not necessarily nice for everyone involved, but I wanted to take that risk.

PROSE: So, okay, the obvious question: Have your parents read it yet?

SHTEYNGART: No. They have not read it. I thought that if they’d read it, they would want me to change things, and I didn’t want to. I didn’t want this to become a bargaining sort of thing. I wanted to paint them as honestly as I could.

PROSE: It’s very fair-minded. That is, the reader doesn’t feel that your parents are just these two misguided people, and everything’s their fault. We feel: Here’s over 70 years of horrifying history funneling straight into you and your family. Funneling onto them and funneling onto Gary.

SHTEYNGART: There were all those horrible things my father talks about—I have at least one relative who committed suicide. You look at those photographs, and they were all wiped out one way or another.

PROSE: There’s that story you tell about the relative running through the fields to survive, after watching his family die. My god.

SHTEYNGART: It’s the combination of Hitler and Stalin. That’s the thing. I went back to that place where my grandfather died [a battlefield outside the village of Feklistovo], and without that death, a completely different story would’ve taken place.

PROSE: The hard things about your childhood were partly the fault of history, of the times your parents lived in, the stresses they lived under. I mean, people who are rich and happy and have easy lives can just pay some kindly Jamaican person to be nice to their children.

SHTEYNGART: Right. But the thing is, I’ve been in psychoanalysis for a long time. And really the big question of analysis is simple. A lot of it is obviously about my parents, and that question is: How much of it was them? How much of it was the Soviet Union, and how much was family, how much was society?

PROSE: So how have you figured out the exact proportions of that?

SHTEYNGART: Forty percent Stalin, 30 percent Hitler, and 30 percent everyone else. [laughs] Their anxiety was palpable, obviously. It was the way I was raised—scared of everything.

PROSE: Well, as you’re about to find out, the sense of being unable to protect your child from certain things is the worst possible feeling.

SHTEYNGART: And they had a lot to protect me from. I mean, they had to get me out of there before I had to join the Red Army, because I would have been killed in a day.

PROSE: And even after you got to this country, there were still things to protect you from that they didn’t even know about.

SHTEYNGART: In a sense, it got worse, didn’t it?

PROSE: Because they knew where the danger was coming from in Russia. And here it’s just so free-form.

SHTEYNGART: A resettlement agency my mother worked for put out a book of essays written from the point of view of my generation of immigrants. One woman wrote about how she went to Hebrew school in San Francisco, and it was the same kind of stuff I went through, and then they transferred her to a nice public school, and everyone was multicultural there, and her life became normal again. So this is not exactly new. When I graduated from Hebrew School and went to Stuyvesant, my life kind of really began.

PROSE: If you can’t torture your own kind, whom can you torture?

SHTEYNGART: I was a jackass in many ways. I projected that cruelty towards others, that kid whose hand I was wringing. If I could have hurt a hundred weaklings—weaker than me, and I was already very weak—I would. I was dying to hurt somebody, to pay it forward, you know? Even writing that, I felt very sad about it. It just rolls downhill. It’s a cliché, but the shit rolls downhill.

PROSE: Do you have any idea what happened to him?

SHTEYNGART: Who?

PROSE: The super-pariah of the Hebrew school, the one everybody hated? Like Piggy in Lord of the Flies.

SHTEYNGART: No, poor kid. We read Lord of the Flies in Hebrew school, and I remember thinking, “Uh, this is a little too close to the truth. Shouldn’t this be vetted by the rabbis before we plunge into this?”

PROSE: Group dynamics. You don’t really have to have had to deal with Hitler and Stalin to want to pick on someone weaker than you.

SHTEYNGART: That stuff just helps. It helps because it politicizes it. You know, when I’m torturing the kid, I’m quoting 1984.

PROSE: It’s hilarious.

SHTEYNGART: But there was just so little pleasure in writing that. I woke up every day and I knew what I had to do. I mean, there was pleasure in sculpting the sentences. But it wasn’t like, “Oh, today I’m going to tackle being beaten up by what-have-you.” Basically, all it involved was waking up and saying, “Okay, I’m 9 years old today—what is it like? What’s the day like? What are my interactions with my parents?” And then you go into that mode.

PROSE: Did anything make it easier?

SHTEYNGART: Setting it in the present tense is what enabled me to make that happen. The present tense was wonderful. It really, really helped.

PROSE: With present tense, it’s like a movie—very cinematic. You’re writing it and you’re watching it happen.

SHTEYNGART: That’s a good way to put it—you’re watching it happen. And I tried to get all the details down, and then all the research, visiting every single spot in [St.] Petersburg. The only place I missed was Yalta. I wish I’d had time to go there.

PROSE: I’ve always wanted to go to Yalta.

SHTEYNGART: Oh, it’s beautiful. It’s very Chekhovian, if you will. Chekhov all the time. On your hotel TV, there’s only the Chekhov channel.

PROSE: But how un-Chekhovian of you to torture the weakest kid in your Hebrew school class. Admitting it in your book was brave. But you know what? I thought that it was even braver of you to admit to having been a Republican. I once had a student from the former Soviet Union who said, “If you say you’re Republican in New York City, you’ll never get laid in this town again.”

SHTEYNGART: That’s good that he realizes that. There should be a big banner across Lincoln Tunnel, “Go Republican, Never Get Laid Again”—for a long, long fucking time. I mean, I was a Republican. I was at a George H.W. Bush victory party. But how could I not have been?

PROSE: How could you not have been? I have friends with Russian parents who are still Republican.

SHTEYNGART: Oh, my parents are definitely conservative. There’s that part in the book where my relative says, “Obama should be president. But of African country. This is white country.” It’s not a culture that privileges empathy for other people. You stick to your own kind. In a way, it’s almost like Italy. But Italy has sun and tomatoes, and Russia just has real problems.

PROSE: Little Failure is a great title. How’d you come up with a two-word title that’s funny?

SHTEYNGART: Now for this, I’ve really got to say, “God bless my mom.”

PROSE: “I wanna thank my mom—for making it so easy for me.” I have to tell you that your book also made me want to go into therapy immediately.

SHTEYNGART: Well, this is psychoanalysis, this is four times a week. I dedicated the book to my parents and my analyst. That pretty much sums it up. All three were helpful in their own way. The big point of analysis for me was that I say something and it comes back to me. So I say, “I’m a bad son,” and there’s silence instead of affirmation. And that was the big thing.

PROSE: Instead of affirmation or denial.

SHTEYNGART: Because you’re programmed a certain way, you know, you’re a Republican, you make money, you do this, you do that, and if you don’t do that, then you’ve failed your parents.

PROSE: But now you’ve given them a grandchild. So you’re a big success!

SHTEYNGART: I think that my parents will be very good with grandchildren because my grandmother, whom I loved more than anything—

PROSE: The way you write about her is so beautiful.

SHTEYNGART: But I don’t think she was a great mother. I don’t think she treated my dad the way she treated me.

PROSE: It’s a mystery, Russia has all these beautiful young women, and then at around 19 or 20, they just fall off a cliff and turn into babushkas. And then these harsh, difficult parents, it’s as if they fall off a cliff and become lovely, adoring, selfless grandparents.

SHTEYNGART: I think that’s right. I see that a lot. It’s interesting to see other immigrants go through this and to see the connections we share at the root. At Stuyvesant, out of a few thousand kids, there were half like me and half Upper West Side kids, and now the proportion’s more: two-thirds me and even fewer native-born kids. But somebody has to take the first step, because getting out of Russia was the best thing my parents did. I mean, that country will never amount to anything.

PROSE: Did you see the Pussy Riot documentary?

SHTEYNGART: I loved it.

PROSE: Those poor girls.

SHTEYNGART: And the conditions are continuing …

PROSE: The parts of your book about America are very good. I love anything that makes me see the country as if I’ve never seen it before. Stripped clean of familiarity.

SHTEYNGART: Well, my challenge was that I’d written three books that had that same kind of approach. In a way, the memoir feels like giving away the story, the story behind the story. This is where it all came from. So part of me thinks that now I have to write about something else, which is fine. I’m ready for a WASP-y character or—

PROSE: So now we’ll get Gary’s John Cheever novel.

SHTEYNGART: [laughs] I know.

PROSE: I was going to ask you that: Do you think that having written the memoir is going to change your writing? It has to change your writing. After I read the memoir, it wasn’t as if I loved your novels less. I’d been entertained and I’d laughed and been moved, the same way I was when I read the novels. But reading this, I thought, Everything that happened in the novels was like a great big cakewalk compared to this.

SHTEYNGART: And writing them, too, was a cakewalk. When I wrote Absurdistan, it was, in a way, the least personal book, because the main character is a 325-pound fat guy, son of an oligarch, et cetera; that’s not about me at all.

PROSE: But there is that 325-pound guy inside all of us. I keep thinking about that terrifying scene where your dad whispers in your ear, “I burn with a black envy [chornaya zavist’] toward you. I should have been an artist as well.”

SHTEYNGART: There’s a reason that he says that. And I think at one point in writing the book, I wondered, Is it because we’re speaking Russian?

PROSE: There is no “burn with a black envy” in English. It’s such a Russian phrase.

SHTEYNGART: The phrase is Russian, but the reason he would say this is that, in Russia, you could say whatever you want to your child. “You’re a miserable, failing kid.”

PROSE: Whereas in English, you look it up first in a baby advice book to see if it’s the right thing to say.

SHTEYNGART: I have a good friend who’s a writer, also an immigrant. His mother spits on the floor and then she says, “You are not worth the spit on the ground.” [laughs] It’s much more melodramatic and expressive than whatever you would say to your kid here, like, “Gee, Jamie, you’re underperforming a little bit.”

PROSE: Or, “Can we talk about why Mom spit on the ground?”

SHTEYNGART: But the thing is, I feel for my parents. I mean, this doesn’t happen out of nowhere. Certain incidents my mother talks about involve a lot of rewriting history. Which is what Russians do well.

PROSE: Everybody does. One thing I found so affecting about your book is that it reminds you of the fear. First, it’s your parents’ fear, and then it becomes your fear: the fear that your life could really not work out. At all. The fear of failure—big failure.

SHTEYNGART: And that doesn’t fully go away.

PROSE: At any point?

SHTEYNGART: At any point. You know, the last book I wrote was set in the future, and it was a very easy book to write, in a way, because it was about the fear of everything falling apart on a grand scale—the whole country falling apart. And I think when my parents watch Fox News or they watch an even scarier Russian channel, that’s the big fear: that they brought us here, they brought me here, and then—

PROSE: It’s going to fall apart. Another empire down the drain.

SHTEYNGART: Exactly, it’s like every empire I touch just falls apart.

PROSE: [laughs] Right. I’m the kiss of death for empires.

SHTEYNGART: Well, that’s the kind of backgrounds we come from, and here’s the thing: It motivates us to do unbelievable amounts of work. Nobody wants to do what we do, you know? It’s insane.

PROSE: It is insane. Graphomania. It’s a real illness. You write so well about writing as a way of making sure you’re loved—I’m writing this, so love me. I liked the part about your grandmother giving you cheese as a reward for writing. If you didn’t call the book Little Failure, you could have called it Writing for Cheese. So are you going out on tour?

SHTEYNGART: Yes.

PROSE: Do you think that’s going to be weird?

SHTEYNGART: You mean with the kid?

PROSE: No, with your readers.

SHTEYNGART: Now they know everything. And this time I have to read from my actual freaking life. I expect some angry Russians, obviously. I love these tours. I was in San Francisco, and a woman gets up—she’s Russian—she’s very angry at me and says, “Do you know you are writing this, but do you also know they are killing Jews at San Francisco State University?” I think I came up with a quick rejoinder, like, “Oh, where do I get in on that?” Or something like that. Then she said, “You know, I have a very lovely daughter in Los Angeles. You should meet her if you’re going there next.” I think I said, “But they’re killing Jews at UCLA!” So I imagine some angry Russians will show up.

PROSE: Okay, I’m going to say one last thing, a sort of New Agey thing, and then—

SHTEYNGART: Please, no, bring it on.

PROSE: What a gift for little Johnny.

SHTEYNGART: This book?

PROSE: This book. In case he’s ever curious about where he comes from, in case he wants to find out, it’s the most beautiful document about his father and his family and grandparents and great-grandparents that anyone could possibly write.

SHTEYNGART: One of the nicest things I’ve heard about the book so far was from someone … I don’t think you should quote his name, you may know the writer. Anyway, he said to me that after he finished it, he wanted to give it to his children who are about to go to college. He came to this country later than I did, at a later age, but some of the immigrant stuff is very transferable. And he said that the book could help his kids understand him a little better. That made me feel good.

FRANCINE PROSE’S NOVEL LOVERS AT THE CHAMELEON CLUB, PARIS 1932 WILL BE PUBLISHED THIS SPRING.