Gary Indiana Coughs Up Some ‘Hairballs of Insight’ About New York City’s Vile Days

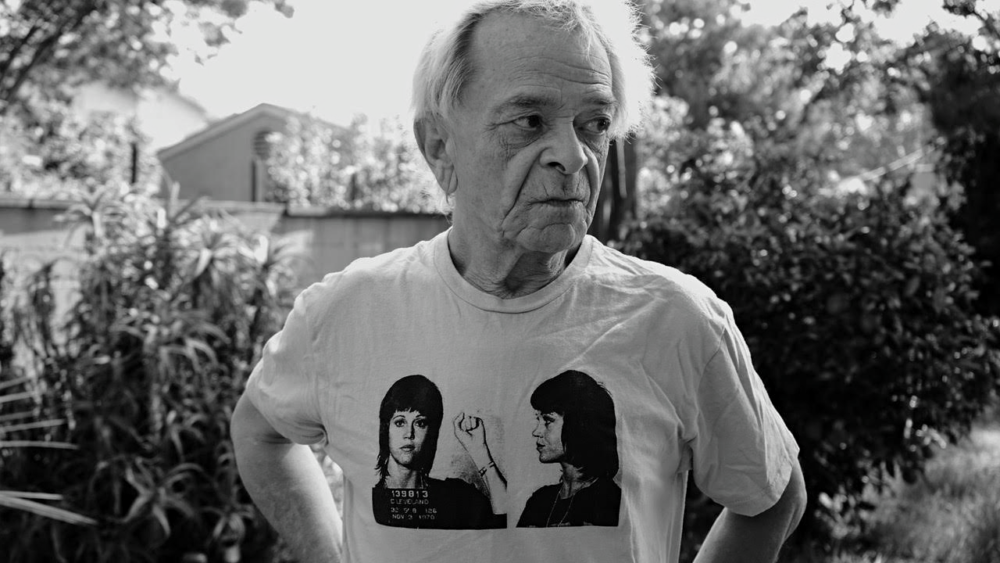

Photo by Hedi El Kholti.

It’s debatable whether New York City’s vile days are truly in the past. You might be hard-pressed to find oil drum bonfires on the High Line as you make your way to Hudson Yards, Koch-era graffiti on the 2nd Avenue 7-train extension, or “people of means” commencing in the act of phone sex with nearby prostitutes from the comfort of their luxury automobiles in the East Village. The last anecdote belongs to novelist Gary Indiana, who captured the more base impulses of the city — its residents and its art-makers — during his three years as the head art critic for The Village Voice from 1985 to 1988. Indiana’s columns have been collected by the imprint Semiotext(e) under the name Vile Days. His writing comes across as an effortless amalgamation of art world criticism and searing social commentary that offers new context to the late 1980s, a well-trod nexus of cultural mythology.

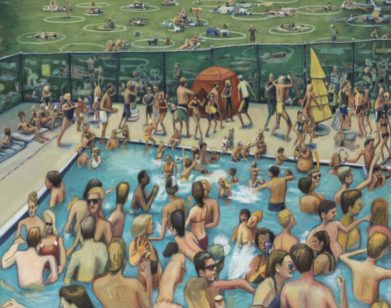

This was a time when artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Richard Prince, among others, were attempting to make sense of a city on the verge of an unimaginable transformation. “You knew it was finished when the methadone clinic moved out,” Indiana writes of the East Village in the preface to Vile Days. Indiana, too, tackled this burden in his weekly dispatches from galleries across the city. Venality, quality of life, climate change, AIDS, and Julian Schnabel were frequent villains, or foils, in his columns. “I was damned if I was going to fucking review art every week without talking about things that were of concern to me,” the 69-year-old explained to Interview at a quiet East Village diner recently. He still lives in the same apartment where the columns, and his subsequent novels, were composed — with frequent escapes to Europe, as he makes clear. Once Indiana retired his critic’s cap, he turned to fiction, creating a legend as an author of savage urban noirs that, naturally, circle around the criminality of the art world, journalism, and the culture industries. Or as one blurb puts it more directly, “the despair and hysteria of 20th century America.” Two of his novels, Horse Crazy and Gone Tomorrow, have been recently reissued by Seven Stories Press and are natural extensions of his time spent in white cubes or dining with the makers of culture at Indochine.

Our quality of life has, to be sure, evolved. But venality, Indiana pointed out during his conversation, still pools in the arteries of this supposedly tamed city. Racism is still choking the city’s public education system. To make way for the “dildos in the sky,” as architectural critic Kate Wagner described Hudson Yards to us recently, the city applied some $6 billion in taxpayer money for the development. One-bedroom apartments start at $5,200 a month. Vile days, it seems, are far from over, but does the art world know this? — NATHAN TAYLOR PEMBERTON

–––

SAM MCKINNISS: You provide a nice definition of art, and by extension, of art criticism in Vile Days. You write, “Consider, though, that our quality of life is the only pertinent subject of art, and we must now and then go over it with a magnifying glass.” That’s a really excellent definition of art from a critic’s perspective. What was the quality of life in New York City during this period of the 1980s?

GARY INDIANA: I don’t like the phrase “quality of life,” actually, but I think the art that I respond to enlarges my own idea about what it’s like to be alive now in this particular time. Some things are true about being alive all the time. There are aspects of human life that are never changing, somehow. Contemporary art shows what life is like at a given time. In the 1980s, there was a feeling of acceleration, but that was true in the 1960s as well. Now, things are even more accelerated, and I see that reflected a lot in art and writing.

MCKINNISS: While reading your columns, I thought that it might’ve been a fun job, although it was probably stressful at the same time.

INDIANA: It was very stressful because of the deadline. You can’t miss a deadline. It’s strange. If you have a deadline, you don’t miss the deadline. Sometimes I would be writing right up to the edge of the day I had to turn it in. It was exhilarating in a way, but not the kind of exhilaration I would care for at this point of my life. I would say, more often than not, I wrote at the last possible minute.

MCKINNISS: A lot of that stress turns into a kind of bitchy humor. The stress is humorous, but it also shows off your facility with the language as well as your willingness to proffer judgment on an artist or show. Was it fun to be bitchy?

INDIANA: I never thought I was being bitchy, particularly. I was just saying what I thought.

MCKINNISS: In most contemporary art criticism, it seems people are slow to say what they actually feel or think.

INDIANA: I was never particularly invested in spending my life reviewing art. I knew it was going to come to an end sometime. I suppose if you’re in an institutional situation where you feel you’re going to have to cough up some sort of hairball of insight every week or every month for the rest of your life, you’re more careful about the way you express yourself. It was well understood by people who knew me, including a lot of artists who knew me, that I wasn’t going to be doing it forever. If people felt uncomfortable with what I was doing, they could console themselves with the fact that somebody else would be doing it real soon.

MCKINNISS: There was another line from one of the columns that I like: “Some critical writing ages better than its subject, though that circumstance carries its own peculiar pathos. Mainly, criticism reflects the preoccupations of its era.” I think that a lot of people are reading the book as a way to glean or look closer at what the preoccupations of that decade were.

INDIANA: In some cases, I wrote about artists who weren’t remembered, and in other cases, those who became very famous. It doesn’t really matter. I mean, it matters to them, of course, but I think that the writing holds up, and it’s still about something. It’s about thinking. I never wanted to be like, “thumbs up, thumbs down” about anything. I was never in the business of making or breaking anybody’s career.

MCKINNISS: You argue certain tastes over others. You champion certain people over the course of the book. I’m using that term “champion” loosely, but you’re definitely in favor of some people. And you definitely paint some people in a more miserable light.

INDIANA: Well, I lived here in [the East Village], and at a certain point all these galleries sprang up. I think my opinions on the works in question have changed, maybe, but a lot of it was sort of inspired by the idea of neo-expressionism. I really disliked it because I didn’t feel there was any validity behind it. The people that were doing neo-expressionism were like 18 years old. Sure, you guys have a lot of inner anguish, but wait until you’ve had a few decades of disappointment. Then, there was another, I don’t want to say school, but another tendency, which was more neo-conceptual, more photography based in many cases. That appealed to me much more. I argued for it because there was more to hang onto mentally and emotionally, to a degree.

MCKINNISS: A lot of the people you argue for in the book were in their early careers. Today, they have important, impactful art shows and things to say, new things to do, stuff to grapple with. Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, who is a close friend of yours. Haim Steinbach. Richard Prince, over and over again. We’re still under the influence of their careers because they’re still happening, right?

INDIANA: I could see that these people were doing something that was legible to me. I hate the word “challenging” because words like that don’t mean anything anymore. They’re so overused. Their work was the opposite of the narcissistic and self-absorbed neo-expressionist stuff going on here in the 1980s. That work, you’d look at it and say, “This is completely cynical. There’s no inner necessity for this stuff.” It was very solipsistic. But, Prince and Kruger, et cetera, they were doing things that caused me to think more — not just about art or what the capacities of art were, but engaged with reality in a way that was directed out towards the people that were seeing it.

MCKINNISS: I couldn’t help but notice other themes pervading the criticism in the book — points that are still worth discussing all these years later: global warming, AIDS. In every other column, these become serious points of discussion. And then also, you write frequently about a culture of venality. Is venality a problem endemic to the art world?

INDIANA: I wouldn’t say it’s special to the art world. It seems to be the lifeblood of this country and probably many, many others. When I was a kid, we were taught money was the root of all evil, and you know what? Still true today. What’s confounding is that the media, which is supposed to inform you about what’s going on, flattens everything onto the same level. Like this business with the Jeff Bezos sexting scandal gets conflated in importance to the eradication of life on Earth and getting rid of the INF treaty. Who’s talking about this? When I had the column, I had a voice that carried quite far. And I was damned if I was going to fucking review art every week without talking about things that were of concern to me. Sometimes, the art was talking about it.

MCKINNISS: Did writing about the New York art world prepare you to write novels about con artists, sociopaths, serial killers, or other characters in American life?

INDIANA: Not directly. What I learned from doing the art column was how to describe objects. It was good for me because I’d always had this terrible inferiority feeling about my writing. I never thought I would be able to write fiction. It was probably because everything I wrote was so solipsistic. It was coming from inside my head. When I did the art column, I’d have to go and actually look at something in the world outside of me and describe it and talk about it. That’s how that was helpful. As for influencing the subjects of my books, you observe people your whole life. Whatever situation you’re in, you learn about certain kinds of people and what people will do, which, unfortunately, is absolutely bottomless. What people will do and what people will do to each other, even at my great age, is a constant shock.

MCKINNISS: The shock gives the writing its energy, its moral force. It’s fun to read. You’re very critical at times, but it’s always fun to be there with you while you’re experiencing the shock and the thrill of it.

INDIANA: I never pilloried an artist unless it was Julian Schnabel.

MCKINNISS: He’s the great villain of Vile Days.

INDIANA: He’s the great villain of the book, although I really don’t think he’s a villain.

MCKINNISS: Neither do I.

INDIANA: He was a good foil because he was being promoted as a great thing, but actually he’s a good artist, he’s a good filmmaker. I don’t regret it because, you know what, you should only pick on people that are bigger than you are. I always thought, “He can take it.” I’m never going to go after somebody that’s only had one show in his or her life.

MCKINNISS: There’s a very funny line from when you reviewed the 1987 Whitney Biennial. It’s a hilarious review, quick and bitchy. You’re just going through the list of notable names at the Biennial and you write: “Bruce Weber should not be in the same room with Ross Bleckner and Annette Lemieux. He should have his own room. It should be in New Jersey.” So I guess you really don’t care for Bruce Weber’s work.

INDIANA: I still don’t care for Bruce Weber’s work, frankly, although I’m not as plangently against it as I used to be. There are much worse things in the world than Bruce Weber. My mental image of him was always somebody who was selling underwear.

MCKINNISS: What was it like to find yourself included in the 2014 Biennial as an artist suddenly subject to criticism yourself? Would you do it again?

INDIANA: Yeah, I would do it again. What was it like to find myself in it? I certainly didn’t lobby for it.

MCKINNISS: To be criticized?

INDIANA: Well, I got very nice notices from various places, and one really shitty notice from Artforum, which makes sense. I wrote for them for 30 years. What do you expect? The Voice and Artforum are probably the only two places I’ve ever worked where there was absolutely no understanding that the only successful business principle in this country comes from the mafia: You don’t beat up on your own people. It was so pointedly personal and gratuitous and wrongheaded particularly because the person just ignored the major part of my installation. She lost her job after that, so what goes around comes around.

MCKINNISS: Much of your writing deals with journalism as a form, but also as a force within contemporary criminal culture. In the preface to your novel Three Month Fever, you write, “The arrogance and inanity that fuels a twenty-four-hour news cycle has earned an amazing amount of contempt in the country at large…People may be entertained by the mindless, predictable, redundant, distorting, and meretricious techniques currently used to cover news, but at heart they despise them. This makes any search for the truth of things something terribly close to folly.” That’s a thought that seems to extend backwards to the art columns, as well as forward, when you were working on your novels. Did you feel like you were participating in the twenty-four-hour-news cycle while writing a weekly column?

INDIANA: Yeah, it was a weekly column and there wasn’t a twenty-four-hour news cycle at the time, I mean, not to speak of. Not like now. The media now, or the people that dominate our attention, Facebook, Twitter, all these things, that’s the point of them, to have your attention. It’s not about giving you the news, it’s about having metrics taken of you 24/7 so that people like Mark Zuckerberg can predict and know everything about your life. You’re the product.

MCKINNISS: What’s a critic’s role in this media environment, then?

INDIANA: I’m not impressed by art criticism, movie criticism, any kind of popular format criticism. I wouldn’t go to the other extreme and say that the only valid art criticism is something you’d find in October Magazine or something. I think most criticism is basically a consumer guide. It’s like, “I like this. This looks good. These are nice pictures, go see them.” Having to come up with some intellectual scaffolding for one’s personal taste is a little bit thick. Nobody should do these jobs for more than a year or two. I’ve always felt that I stayed too long — about half a year too long. Some people can do it. Peter Schjeldahl can do it, A.S. Hamrah can do it. Jerry Saltz can do it, and come up with interesting things, but most people are not able to sustain the same level of quality from week to week. I didn’t. You can’t. After a couple of years, most people just repeat themselves. This is not a grown up’s job.