The Vault

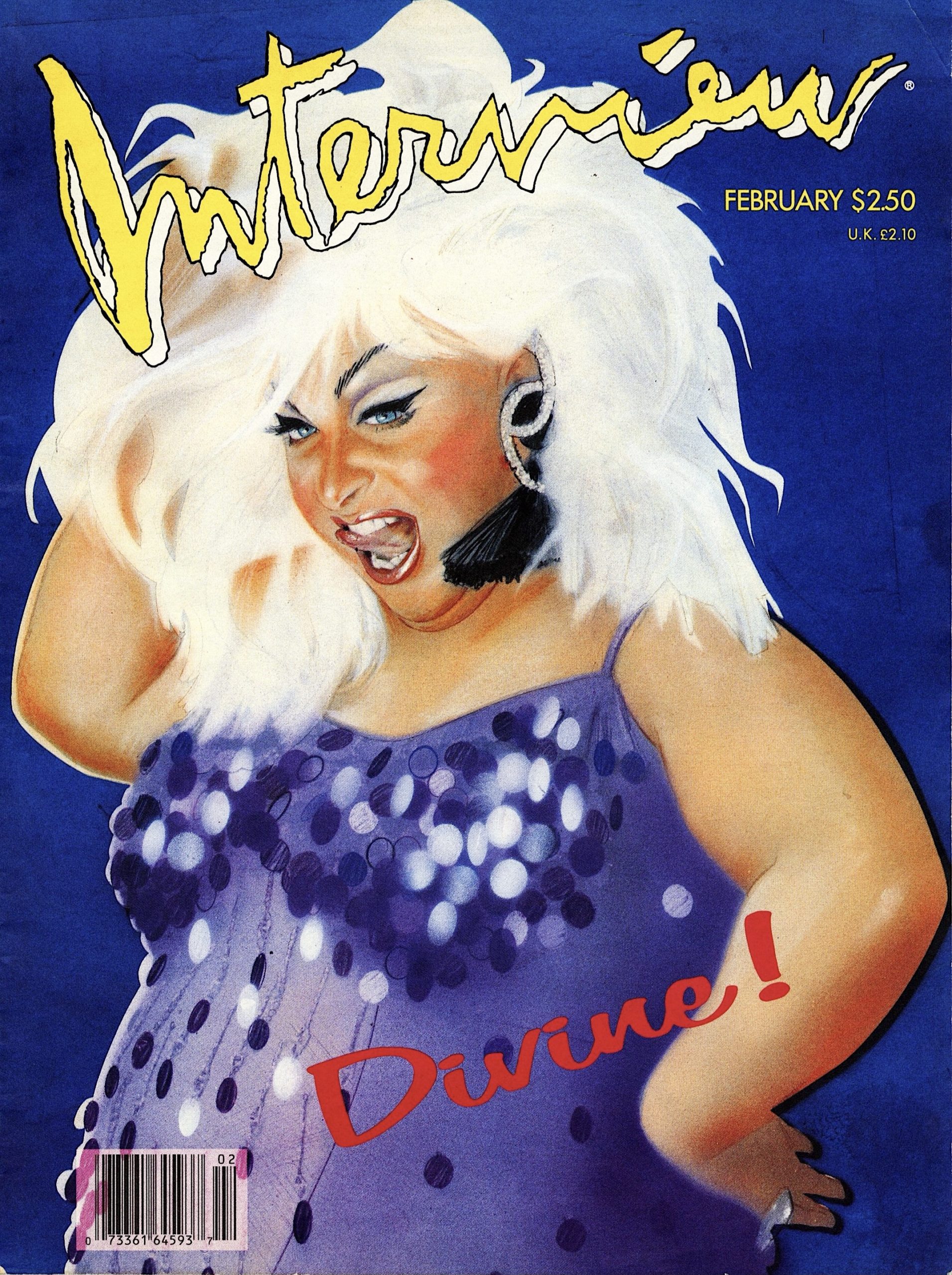

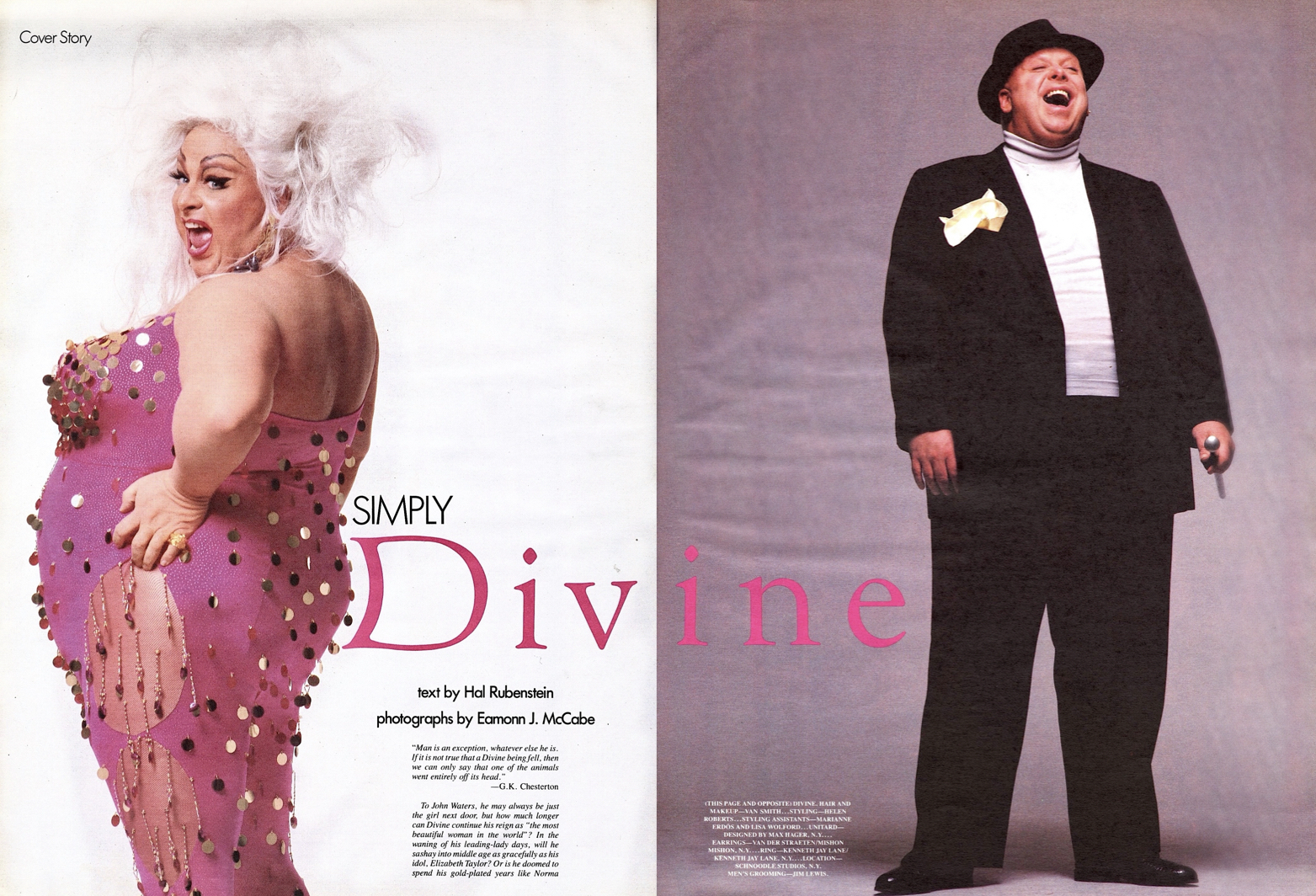

From The Vault: Divine by Hal Rubenstein

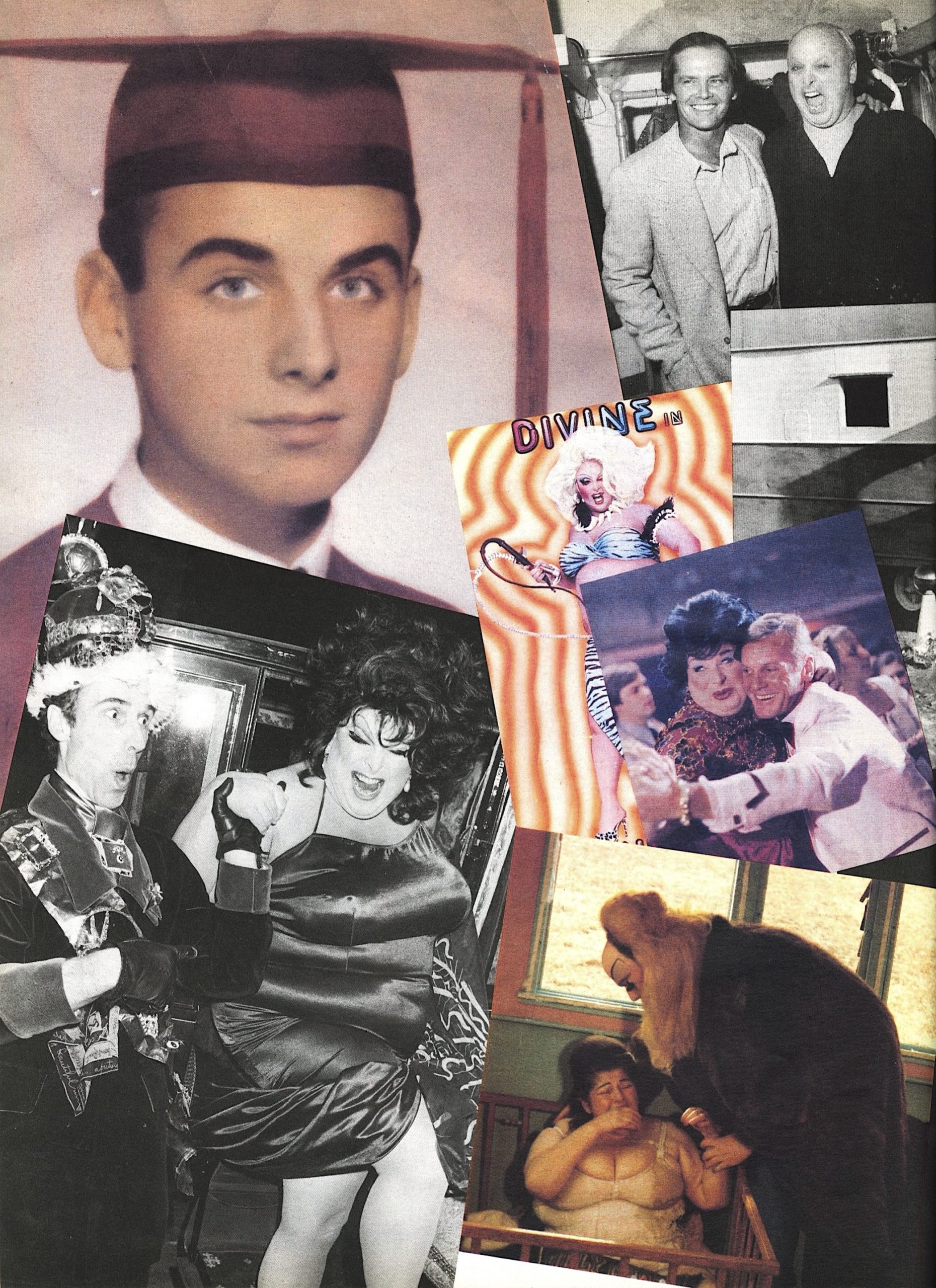

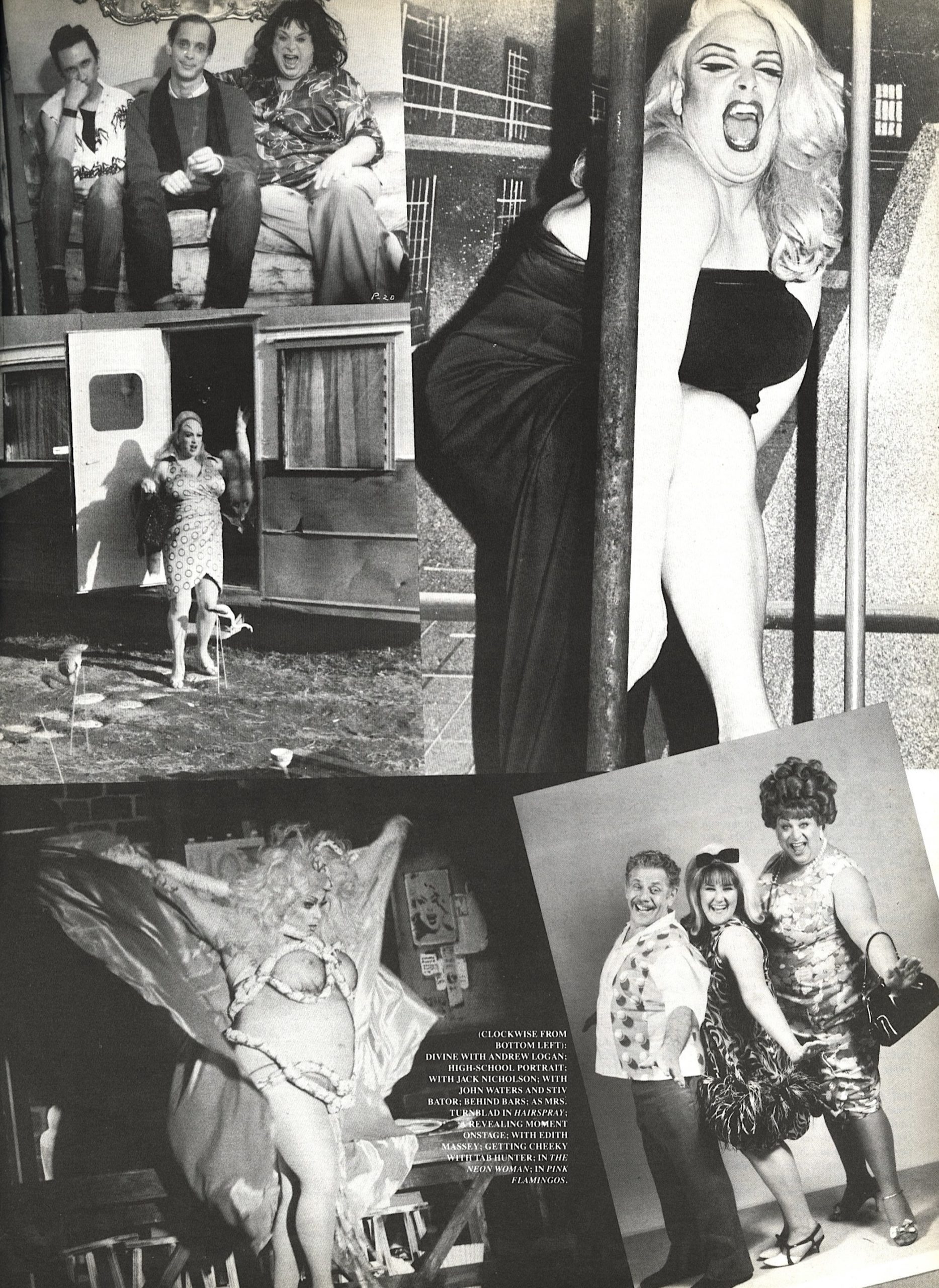

This is The Vault, our bi-weekly column in which we revive a conversation from deep in the archives for your viewing pleasure. This time, we honor Divine by revisiting her Interview cover story from our February 1988 issue. Below, the drag superstar fields questions from Hal Rubenstein about John Waters, Hairspray, and her rightful place in Hollywood. Go ahead, dive in.

———

HAL RUBENSTEIN: Well, surprise, surprise. After fostering a screen image that combined the best of Joan Crawford, Ida Lupinom and Broderick Crawford, you’ve turned into Myrna Loy.

DIVINE: Imagine me, a concerned mother. Now that’s acting.

RUBENSTEIN: You’re practically sweet in Hairspray. Is this your new leaf for ’88?

DIVINE: No, I am sweet. It’s just that no one asked to see this side of me before.

RUBENSTEIN: But you’re so wholesome, so caring. Is this a career turn? Should we be expecting a remake of The Best Years of Our Lives anytime soon?

DIVINE: Well, put it this way: For all those people who always thought I was nothing more than a drag queen, wait until they see what I agreed to look like in Hairspray! Drag queens are supposed to be hung up on glamooouur. Meanwhile, on my first day on location, I came out as Edna Turnblad—in my flip-flops and hideous house dress, with varicose veins drawn on my nubbly shaved legs and everything that is wrong with me accentuated, schlepping along in these pin curls and barely any makeup—and I walked right by the crew. Just kept going. Not one person on the set recognized me or even noticed me, because I looked like half the women in Baltimore. I. had to go up to John and stand face front for him to realize who I was. He was thrilled. I was crushed.

RUBENSTEIN: Initially, I was disappointed that you didn’t have the lead in Hairspray.

DIVINE: Funny, I had the same reaction. I had wanted to do it, to play both mother and daughter, like those Lana Turner movies where she’s 16 years old and then she’s 80. I thought it would add the right touch. But I think the producers were a bit leery, so they hired Ricki Lake to be my daughter. She is 19 and delightful. I hate her. I got to admit, some of those kids were a little young, and no matter what kind of makeup I devised, I wouldn’t have help up next to a fifteen-year-old boyfriend. The camera is so cruel.

RUBENSTEIN: Chronologically, you could easily be Ricki Lake’s real mother.

DIVINE: Thank you so much for reminding me. As if the kids didn’t tell me enough times. But they were sweet. It was great to watch them, because they had never heard of the dances of the ’60s. So John would go, “C’mon, Divine, show ’em how to ‘mash potato’; do the Madison for them.” I mean, they had a dance instructor, but I would show Ricki special steps, in hopes of making her a baby divine.

RUBENSTEIN: Had the kids seen any of your previous Waters films?

DIVINE: Not until John showed them. Unfortunately, I didn’t arrive on the set until they had been shooting for two weeks, after they had seen a few, and judging by the looks on their faces, god knows what they must have expected. But I was just myself—”Hi, how are you? It’s great to work with you”—and slowly they came around and got real friendly. Maybe too much so. Soon they were asking lots of questions, some very personal, and either I told them it was none of their business and how rude to even ask, or I would answer them and then they were really sorry.

RUBENSTEIN: Does Hairspray show what it was like to grow up in Baltimore, or is it John’s fantasy adolescence?

DIVINE: No, I think a lot of it is true. Instead of “The Corny Collins Show,” we watched The Buddy Dean Show. I wouldn’t say we idolized the dancers as much as the kids do in the film. John and I were, how should I say it, from a “different” neighborhood—a snootier part of town. The kids on TV were from South Baltimore, which was a bit…well, we didn’t hang out with them, but you watched it because you wanted to hear the music so you could dance with the refrigerator door. But they weren’t “downtown.”

RUBENSTEIN: What did you want to do then?

DIVINE: I don’t think I thought about it. I was mainly concerned with whether I had my own telephone, my own car, fifteen cashmere V-neck sweaters, and wing-tip shoes.

RUBENSTEIN: You didn’t sit in the movie theater and dream of walking down grand staircases in gold lamé?

DIVINE: No, I always had very macho taste in movies. I love blood and guts and tear-it-ups and shoot-outs. I never miss a Stallone film. I’ve seen all of Charles Bronson’s.

RUBENSTEIN: Then how did this vision in Lycra and Dynel spring forth?

DIVINE: It was definitely John’s idea.

RUBENSTEIN: What a pal.

DIVINE: At first, it wasn’t any big deal. John wanted to make Brownie 8mm movies. He used his friends. He cammed me Divine because he thought I was, and someone else was Mink Stole—her real name was Nancy Stole; she lived around the corner. Someone else was Extreme Unction. John was obsessed with film, so we would get together on Sunday afternoons and make movies. And then during the week we’d meet for Coke and chips and watch them, and we thought we were the greatest things since sliced bread. It wasn’t until they were shown at the University of Maryland and Georgetown University filmmaking classes that we realized that other people thought they were neat too. Then John started giving lectures where he’s introduce me as “the most beautiful woman in the world, almost”; I would could out and have a “modeling fit,” throw a fish at the audience—Baltimore is a big seafood town—and rip telephone books in half.

RUBENSTEIN: Was Divine as foulmouthed then as she is now?

DIVINE: No, but John’s first films were silent. My look was different, too. It was more ’50s and very hard. You also have to remember that though John gave me the name, there was no character Divine; there was just this person named Divine. [His passport even says Divine.] When I first started my nightclub act I had to create her. I took little bits and pieces from the different women I’d played: Babs, Dawn, Francine. Other people still confuse them all and call them Divine, but they’re not—they’re all different. I am Divine, not them.

RUBENSTEIN: But they all share something in common.

DIVINE: Yeah, they’re all bitches, modeled after the most popular women in America: Joan Collins, Joan Crawford, Elizabeth Taylor when she put her heel through Laurence Harvey’s shoe in Butterfield 8. That poor man was crippled for life, but she got an Oscar. Americans love nasty. The big bitch—she’s always been a favorite. I myself am not foulmouthed; I tried to be a Doris Day type. We used to do “The Name Game” in the act—you know, “Shirley, Shirley, bo burley, banana fanna fo furley…” Please. It didn’t work. Audiences are still very much like Romans watching the gladiators. They want raunch, they want spectacle. Ninety-five percent of people who go to nightclubs want to see and hear what they can’t see or hear at home. Sometimes I embarrass myself.

RUBENSTEIN: Yet you are more popular as a cabaret performer in Europe than you are here.

DIVINE: Europeans are not uptight about the female attire. Men have always played women’s parts in the theater. It’s not questioned and no one really cares. It’s just a way to give people a good laugh.

RUBENSTEIN: But if you want to be known as a character actor and want to get more male roles, doesn’t perpetuating a drag character hinder you from changing the perceptions of ready-to-pigeonhole Hollywood casting people?

DIVINE: I have to work. I have a certain way of life I want to maintain. I don’t want to be poor again. Besides, I love what I do. I’ve only been making money for the last five years, so I certainly haven’t been doing this for bucks. At this point, I can’t help it if others have a lot of misconceptions about what I do, if they’re not willing to believe I am a character actor and one of my characters just happens to be a loud, vulgar woman. Nevertheless, it hurts. The other night I had dinner with a friend I hadn’t seen in a while, and he told me his roommate warned him not to eat with me because “God knows what she will do, probably stand up on the table and moon and vomit all over people.” C’mon fellas, give me a break.

People don’t even know the meaning of the word “transvestite.” I don’t live in drag. Now, Candy Darling was a transvestite, and a very beautiful one. But I don’t sit around in negligees and I don’t wear little Adolfo suits to lunch. Of course, if I had a couple of Bob Mackie outfits, things might be different.

RUBENSTEIN: But is the typecasting all their fault? It’s not as if you made a sensitive feature film debut, like Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People.

DIVINE: Pink Flamingos was one filthy word after the other because it was a $12,000 movie playing up against Superman, which cost $40 million, and something had to be done to get us noticed. It was a gimmick. And whether people liked it or hated it, they talked about it and they wrote about it. It was designed to shock and make everyone aware of who we were… except, talk about having a hard act to follow!

RUBENSTEIN: Why is it that you are still haunted by your past, long after Goldie Hawn has shed her bimbo image and Raquel has doffed her 1,000,000 B.C. loincloth?

DIVINE: Because they still want to know if I ate “it.” It’s so old. With everything that’s going on in the world, how can that still be on anyone’s mind?

RUBENSTEIN: At least you admit to your past. Last month in Vanity Fair, Bette Midler gave her revisionist history of playing the baths: “I kind of had blinders on. I never explored the baths and I never went anywhere except the dressing room and the stage and I liked it that way.”

DIVINE: It’s too bad she can’t be more honest with herself. I admire Bette, because look at that career! To have played the baths as this raunchy babe and end up with a Walt Disney contract is quite amazing. But she was awfully aware of what was going on. She wasn’t stupid, what with all the gay friends she had. She was an ambitious girl and knew it was a great following to have as a base—one she badly needed, considering the act she was doing at the beginning.

Gay people were important for me at the beginning too. For many performers. But you can’t turn on them. Bette’s lucky. Look what happened to Donna Summer; she alienated gays, and her career is where? How do you deny the people that gave you your start? I will always play gay clubs.

But what bugs me most about Bette is that when she had her interview with Barbara Walters, she looked right in the camera and said, “And I was the first Divine; I just want everyone to remember that.” I wanted to punch her right in the face. I have been Divine since 1962, when John gave me that name. Was she even around then? How could she sit there and say that? Isn’t it enough to be Bette Midler? God knows she is more famous and makes more money than I do; isn’t there room for all of us here? Like I said, I don’t hate her; I admire her and I love her shows. I thought “Clams on the Half Shell” was unbelievable, though it was the last one that I saw. She has created a place for herself, even if those little rat steps are more Bette than Beverly Hills housewife.

RUBENSTEIN: Do you see a place for yourself in Hollywood?

DIVINE: I always admired Sydney Greenstreet. And I think he and Charles Laughton left a void there that I can fill. I am not saying I’m as good as they were—they were great actors—but maybe someday I will be. I enjoyed playing Mr. Hodgepile in Hairspray, turning into an awful pervert and looking down girls’ dresses. I just finished a film for Paul Bartel called Out in the Dark, with Karen Black, Lainie Kazan, Tab Hunter and the whole bunch from Lust in the Dust. I play a detective, and I loved it.

It took me 16 years to get my first male role, in Trouble in Mind, so no one can say I’m not patient. I’m in no hurry. It’s turning around slowly. I’ve lasted a lot longer than many thought I would. I’ve been working now for 24 years. That’s a long time to be around for playing only one note, and I’m making a damn good living. And if some still think I’m a woman, okay too. I must be a pretty great actor if they still think that.

RUBENSTEIN: Do you think size might have had anything to do with the paucity of roles for you in the past?

DIVINE: Once, in high school, I actually dieted down to 140 pounds. I had a 28-inch waist! I was very Ivy League, with the hair that came down to my mouth, bleached out in the front. Now that the hair and the waist are gone, all I know is that I’m just one of those people who definitely have a weight problem. When I’m thinner I feel better. You put it all on again. I don’t know why. Sometimes it’s scary when you question yourself and you come up with different reasons. I just get hungry, anything that is not nailed down better watch out.

RUBENSTEIN: With the current mania for thinness, are people less tolerant of people with weight problems?

DIVINE: Yes. No one has patience with fat people. They think we’re disgusting hogs. It’s very difficult to watch your weight when you’re on the road so much, eating in restaurants every night. I can’t exactly sit there and set up my scale and calorie counter. The chef doesn’t want to hear about it.

RUBENSTEIN: But there are certain foods you should stay away from altogether, like cream, red meat, sugar.

DIVINE: Sugar? Really?

RUBENSTEIN: Divine! Are you kidding?

DIVINE: Well, I really don’t like sweets, except for ice cream. What about salt?

RUBENSTEIN: Salt makes you retain water.

DIVINE: But I love salt and spicy food.

RUBENSTEIN: But spicy will make you crave sweet.

DIVINE: Well, don’t tell me I can’t have pasta.

RUBENSTEIN: No. Pasta is good. Just keep away from cream sauces.

DIVINE: But that’s what makes it fun.

RUBENSTEIN: But it’s deadly for you. Cream, cheese—they’re mainly cholesterol and fats. You’d be much better off getting a bowl of pasta with olive oil, onions, garlic, tomatoes, eggplant.

DIVINE: I’m right behind you.

RUBENSTEIN: Are you obsessive about eating?

DIVINE: No, but I am a compulsive shopper. The first year I made money I became addicted to Maud Frizon shoes. I don’t eat while I shop, mind you, because it’s not nice to get crumbs on the carpet at Bergdorf’s.

I was also addicted to marijuana. I thought the marijuana was helping me, because it’s no fun getting home from a show at 3 a.m. and not being able to fall asleep until 5. But soon I found I was stoned all day, until I passed out. I started staying at home all the time because I didn’t want to end up out in a club somewhere snoring. I didn’t care about my career, my looks. It certainly didn’t help my weight. When I was stoned I only ate once a day, but the meal lasted 24 hours. I had agents and managers fighting to create a career for me, and my attitude was “Fuck it, let’s smoke.” I became difficult to work with, and I had always prided myself on being so professional. I wasn’t happy.

Finally I realized that I had to do something. But it had to be on my own. I didn’t want to go to a clinic only to be released and smoke my brains out. So I went to Malta, where I usually go in the summer and spent a long time by myself. I did all the corny things: counted my blessings, recalled the bad times when I was on welfare, recalled the good times—like the fight scene in Lust in the Dust when I couldn’t say my lines because Lainie’s tits were in my face—admitted that I was throwing away a good life, confronted the fact that I hadn’t accomplished what I set out to do, which is to be the biggest and the best, and realized that though I was scared because I had lost friends and didn’t want to be left alone, I was live, and couldn’t afford to waste time being negative.

And I bucked it. I moved on. Since then, I’ve gotten more parts, and I love doing my show again. God, it’s hard enough when you turn 40 and all the hair starts to grow in strange places on your body—like you can curl the hair growing on top of your ears into a pageboy—without making it tougher on yourself. I’ve gotten rid of almost all my vices.

RUBENSTEIN: So you are different from the Divine who made Pink Flamingos?

DIVINE: Yeah, I’m older. Wiser. Heavier.

RUBENSTEIN: Happier?

DIVINE: Yeah, now I don’t mind people gaping, because I know if they stop gaping, then it’s all over. The dearest thing to me is my career. And I love being Divine again. I haven’t felt like this since I was a teenager. Maybe I can’t look thirteen anymore, but I have as much energy as Ricki Lake. I was afraid it was all past, but I’m ready to tear it up all over again. I feel confident that I can play anything, whether it’s sleazy Mr. Hodgepile or the big bad bitch, and that others are going to discover that as well. What’s more important is that I know I’m not either one of them. People are going to discover that, too. I’m a nice guy, I really am.