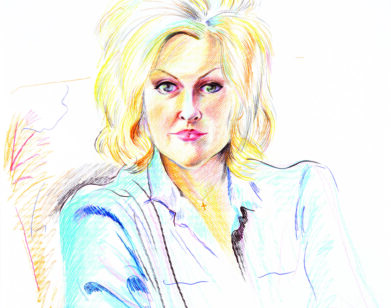

Exploring Under The Bridge With Rebecca Godfrey

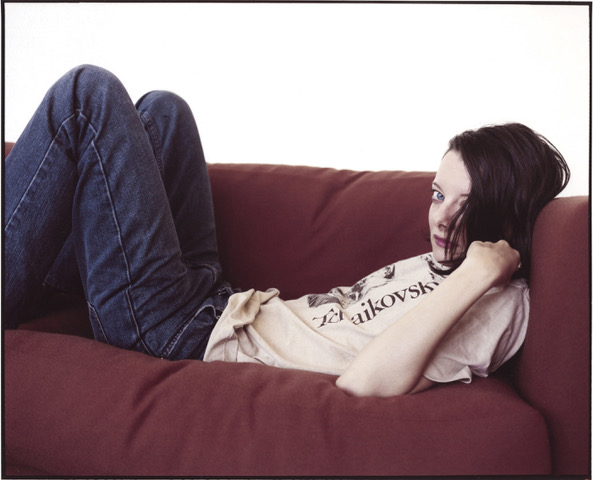

Photo by Brigitte Lacombe.

In 1997, Reena Virk was brutally beaten and drowned by a group of teenagers in the sleepy town of Victoria, British Columbia. Virk was only 14. Although it may sound like the plot of an upcoming scripted series (or a podcast, or a YA novel), it was truly a true crime, one that caught the attention of the entire nation. “The girls all looked like normal, cool, young teenage girls—not particularly like killers,” recalls Rebecca Godfrey, author of Under The Bridge (and former Interview intern). The non-fiction novel, inspired by that incident in 1997, chronicles the “rivalries and hostilities and jealousies” of teenage life in the small town plagued by the murder—which also happens to be Godfrey’s hometown. In light of the book’s recent re-issue, with a new introduction by the author Mary Gaitskill, Interview caught up with Godfrey to discuss her experience revisiting Under The Bridge 14 years later and the renaissance of the true crime genre.

———

ERNEST MACIAS: What led you to research and write the book in the first place?

REBECCA GODFREY: I was living in New York City. This would’ve been in the late 90s, and I was working on a novel about teenage girls in my hometown of Victoria, British Columbia. Then I started getting all these calls from friends that there had been a murder in Victoria. I went home soon after and went into the prison. I was just stunned because the girls all looked like normal, cool, young teenage girls, not particularly like killers.

MACIAS: In reading the description of your book, there was a line that really caught my attention: the book “highlights the deeply entrenched social tensions that provoke the murder.” What are those tensions that led to the murder?

GODFREY: It was interesting because it was all such a big media story. The Canadian media in particular took this tact of these kids being monsters, and there was a lot of talk about gangs, even though they were suburban kids. As a result, a lot of the teenagers were really sort of abandoned by the adults in their lives. Another sort of thing at the time—it was the late 90s—there was that influence of hip-hop. There was this whole conversation about hip-hop, because they were all into N.W.A and DMX, and they had this romantic fantasy of being gangsters that was completely detached from their reality. It was just what they saw on television, it was romantic to them.

MACIAS: Do you find that the same social tensions still resonate today?

GODFREY: I think there will always be, particularly with girls, these rivalries and hostilities and jealousies. That’s just part of teenage life, but it took this dark turn with these girls. I know in Victoria the town, when the murder happened they made a lot of noise about improving and making more services for teenagers, but they’ve done very little. In the book, I talk about how they built a casino, and said that they would use the profits from the casino towards building a youth center, but that never happened.

MACIAS: Lately there’s been a super intense interest—almost an obsession, I’d say—with things that are based on true crimes. What do you think people find so appealing about them?

GODFREY: It’s cathartic or intriguing to see what happens when people suppress these fundamental emotional tensions that we all experience—jealousy, or rivalry, or envy—and then they’re pushed to an extreme. I used Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood as a model of a book that explores a crime as a way to investigate a community or a morality. Most true crime books were seen as déclassé or lurid, and not something that educated people read. There was this distaste for them, and I remember when I would tell people at dinner parties what I was working on, they would wince and not want to hear about it. There’s an elevation of the genre that’s happened. A lot of these series are using a crime as a method to explore larger emotional or social issues, and I don’t think that had been done before. I think that’s why people are more accepting of it.

MACIAS: Were there new things that you learned from revisiting the book?

GODFREY: I have a daughter now, so I find the subject material much more painful and difficult to think about. When I was younger, I was more easily fascinated by it, but now I find it quite troubling. I’ve sort of forgotten how dark that world was, and thinking of all the places I’d gone, I just couldn’t imagine now saying to my daughter, “I’m going to a maximum security, all-male prison.” In a sense, there’s a certain bravery and freedom you have when you’re in your 20s that I was reminded of.