in conversation

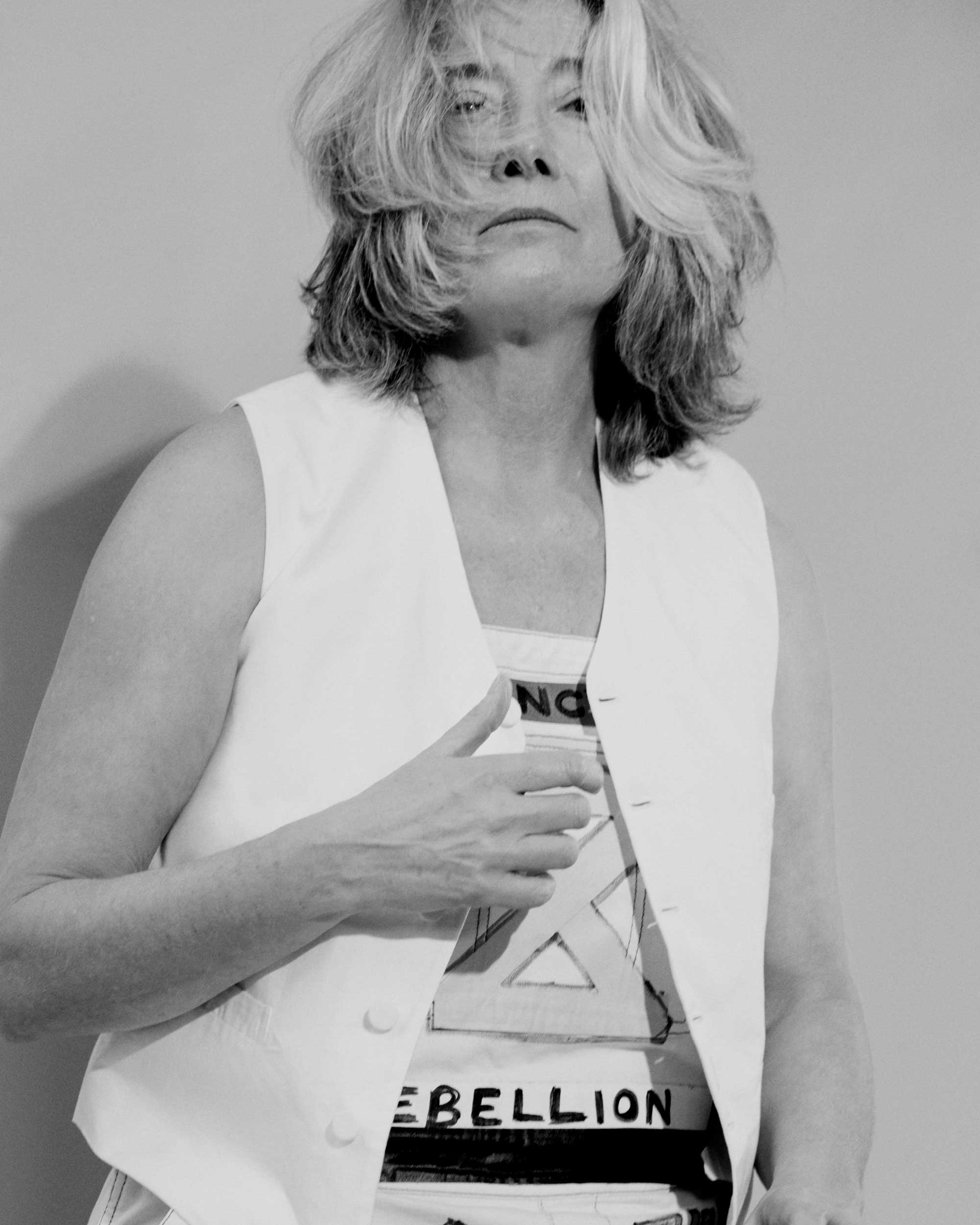

Emma Thompson and Tony Kushner Reflect on a Year of Rest and Resignation

Emma Thompson won the first of two Academy Awards for her role as the kind, level-headed, and loyalty-torn Margaret Schlegel in the 1992 Merchant-Ivory masterpiece Howards End. To watch Thompson over the course of the film’s two-and-a-half hours is to witness precisely what makes the 61-year-old actor the rarest of cinematic talents. Much of the magic of Thompson’s work in the film lies in her tension-filled interactions with other characters (particularly when she’s playing opposite Helena Bonham Carter as her willful younger sister, where their emotional choreography is so nuanced that they finish each other’s sentences ). There are many Hollywood legends whose mere screen presence steals a film; they often seem beamed onto set for the duration of their scenes to enact a moving, star-worthy monologue. But one of the great gifts of Thompson’s career is that she’s less of a scene-stealer and more of a scene-maker.

Whether it’s a period piece (1992’s Remains of the Day or 1995’s Sense and Sensibility), noir thriller (1991’s Dead Again), Shakespearean adaptation (1993’s Much Ado About Nothing or 2018’s King Lear), fantasy children’s epic (the Harry Potter series or 2005’s Nanny McPhee), gripping biopic (1993’s In the Name of the Father or 2013’s Saving Mr. Banks), comedy (2003’s Love Actually or 2019’s Late Night) or political dystopian horror (2019’s Years and Years), Thompson always seems to be engaging with her fellow cast members, bettering their performances by way of her own. There’s a palpable sense of comradery in her craft, as if her work raises the bar of an entire project and all who move in and out of its constellation. It’s no surprise to learn that she is the daughter of two British stage actors who were workaday touring thespians rather than West End luminaries.

Thompson may claim to be more interested in rest than exertion these days, but in recent years she’s taken on a fleet of diverse roles. Chief among them is her turn in this spring’s punk-rock origin story of Cruella de Vil, the fashion-forward villain of 101 Dalmatians. Set in 1970s London, the gleefully rebellious live-action film Cruella feels as if Vivienne Westwood gave Walt Disney a makeover. Thompson plays Baroness von Hellman, an eccentric fashion pioneer who takes a young street-urchin misfit (the titular would-be dog-snatcher, played by Emma Stone) under her wing. The spectacular costumes alone are worth the price of admission, although Thompson is game to do the job of out-camping her clothes. Cruella finished filming shortly before the pandemic hit, and Thompson has spent her year of lockdown with her family in London. Soon, though, she’ll be back at work, on the set of three new U.K.–based films.

Thompson and her friend, the Pulitzer Prize–winning writer Tony Kushner, first worked together on the brilliant 2003 miniseries of Kushner’s play Angels in America, directed by the late Mike Nichols. Talk about using Thompson’s theater chops to great effect: She played, among the menagerie of her roles, the Angel America who crashed through the ceiling to herald a new age. We are again living in a new age, with much Great Work needing to be done. Thompson and Kushner, both social activists, know this only too well.

———

TONY KUSHNER: How’s London these days?

EMMA THOMPSON: It’s a bit dismal, if I’m honest. We went to St. Paul’s last night to a service to support The Good Grief Trust, because Greg [Wise, Thompson’s husband] has been doing a lot of work with people who deal with grief. It was very touching. We were in the cathedral, which is a place that normally seats about 2,500 people, with about 250 people who were seated at vast distances from one another. There’s so much grief everywhere. Yet, I have met people who say, “I’ve been great because I’ve spent time with my family, I’ve been reading books, etcetera.” I had a lovely meeting with a young writer who said, “I spent lockdown writing about the 1871 Paris Commune at the BBC.” So it’s terribly sad but there is hope that there are great things happening. Is that what it’s like for you?

KUSHNER: In a way. It’s a terrible situation over here, too. The last four years have felt like 50, and the last two or three months have felt like two or three years. Every day feels like a month. It’s horrifying. And now it’s not just us. You see Angela Merkel getting booed yesterday because the far right was upset that she was saying that Germany isn’t doing a good enough job slowing down the rate of infection. It’s an international problem now.

THOMPSON: It really does seem to be.

KUSHNER: The idiots and con artists and anti-science people and theocrats have all found each other and have given each other permission to abandon any sense of shame. Everybody’s trying what Trump tried with such monstrous success over here. These people are all feeding off the same poison. Anyway, how are you?

THOMPSON: Now that we’ve got that out of the way, I’m fine. But it really has been such a strange and difficult and, in some ways, extraordinary time. Apart from the geopolitical horrors, there have been silver linings like spending eight months with my mom, who has Parkinson’s, at age 88, and with Gaia [Wise, Thompson’s daughter] who just turned 21. I’m actually staring at a little installation I made of all her baby clothes, the ones I kept in a box in the loft for this occasion. I’ve taped them up on the little clothesline in the kitchen. I’m grateful for the things that have been good.

KUSHNER: Were you able to film at all this year?

THOMPSON: We finished filming Cruella in November of 2019, so I haven’t worked in a year, which I’ve loved.

KUSHNER: Have you been doing any writing?

THOMPSON: I’m writing the Nanny McPhee musical, but that’s an ongoing project that’s going to take forever. I’ve found it quite difficult to concentrate and I wasn’t reading very much either. Have you read much?

KUSHNER: I’ve been reading and writing a lot, which is surprising. I’m relieved in a way not to have to do anything I used to do to have a life. It’s been interesting to feel all that stripped away. To be stuck at home with a feeling of quietness. Like that Henry James story, “The Great Good Place,” there’s this retreat from the tide of emails and obligations. It’s what Mike [Nichols] used to say: The best thing in the world always was to have someone cancel an appointment.

THOMPSON: He always said that was his favorite thing. A cancellation of any kind.

KUSHNER: He said that the whole point of making dates with people is that there was a possibility that you might be relieved of the obligation to show up.

THOMPSON: It’s so true. Having had this year, what are the things that you realized you don’t ever need to do again?

KUSHNER: Going to the theater. I don’t really mean that, although I’m surprised at how much I don’t entirely miss theater. It’s terrible and I really feel like I should, because I work in theater, and I feel terrible for all of us theater people who haven’t been able to work. But theater is hard. It’s hard to show up at a certain time and be in a room with a lot of people and watch other people do things that might turn out to be terribly embarrassing.

THOMPSON: It can be a nightmare.

KUSHNER: The thing I miss the most is riding the subway.

THOMPSON: Is it closed down?

KUSHNER: It’s not closed, and I did take it once when things had calmed down. But I’m 64, I don’t want to share a closed space with anybody right now. You know, I was googling around and found an interview you did a year or two ago where you talked about turning 60. In this piece you said that you felt as if you were immortal until you’d turned 40. Then it started to register. I felt very much the same way. Have you, in the last couple of years, started to feel a bit posthumous or ready to retire?

THOMPSON: I actually think in this middle patch, if you’re lucky enough, like we have been, to turn 60 and still be A, extant, and B, working, it can be a truly interesting time. Honestly, from the point of view of acting, I feel like I could do anything now. I feel completely fearless. But I also feel fearless in the sense that if nobody wants me to act, that’s fine, too. I’m fine to go and sit under a tree and stare at it for the next however long I’ve got. Truly I am. I mean, if I were to die now, it would not be good, it would not be helpful to my children and all of that, so I’m going to try to stay alive. But otherwise, I’m fine. Do you know what I mean? I’m not reaching for anything. In fact, I’m somewhat hibernatory.

KUSHNER: I love that you call this the middle patch, so that means we’re both going to live to be 120, which I’m very glad to do! When you were starting out, did you have a sense of a large-scale project? Like, “This is what my life is meant to accomplish.” And now that it’s been 60 years, can you look back and say, “I did it, so if I get hit by a bus tomorrow, apart from the problems that it would cause the people I love, my last thought won’t be, ‘Shit, I didn’t get to play…’”?

THOMPSON: … The Thing.

KUSHNER: Right. I didn’t get to do The Thing.

THOMPSON: That’s never been my kind of thinking. Right from the start, it was just a question of, “What’s happening? What’s going on? What shall we do next?” I’ve never understood the word “career” when it comes to our line of work. A career is something that you can see, like tiers, an arrangement, a structure. We don’t have that. I suppose you get to play bigger parts as you go, but even that doesn’t apply. Because when you’re my age, you get to play quite a lot of really nice small parts, which can be just as much fun and marvelous, because then you can take a bit of time off. You can afford to. But I’ve never felt like I had a career. I just go from one job to the next, and someone comes up and says, “Have you tried…?” Whatever it is, writing some comedy sketches or a screenplay or doing a musical, I’ve gone, “That sounds exciting. Yes, I’d love to try that.” That’s all it’s been, actually.

KUSHNER: Both of your parents were actors. I think there’s a different mentality of people in theater and film in England versus the United States. There’s a degree of panic and anxiety in the U.S., where having a career in the arts feels somehow aberrant. It wasn’t until I started doing theater in London, when I met people like the Redgrave clan, that I saw it as a family business that people had done for generations. Do you have a memory of your parents being actors?

THOMPSON: People say, “Your parents are in the theater, like the Redgraves or the Foxes or the Cusacks”—those proper theater dynasties. Ours wasn’t like that. My parents were completely penniless actors. I was born unexpectedly, and they had no money at all. Dad would have described them as “journeyman actors,” that is to say, people who went to theater school and never expected to do film, because there wasn’t the same kind of industry here in the 1950s and ’60s. They basically expected to do a selection of about five different accents, and quite a lot of Shakespeare in touring theater companies, which is exactly what they did. I went to see my mum when I was about 7 in As You Like It at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre. I loved that, because you got a rough, army-issue blanket to cover yourself in your deck chair. I was born 15 years after the end of the Second World War, and London was still dark and sooty. The last pea-souper, as described by Conan Doyle in Sherlock Holmes, was in about 1961. My mom and dad would say, “You literally couldn’t see the person on the other side of the stage, because the fog of pollution was so bad.” I wouldn’t say I came from an impoverished background, but it was life very much on the edges of just managing to get by.

KUSHNER: Did you understand that Shakespeare production as a 7-year-old child?

THOMPSON: Yes, I remember it so well. I remember going backstage and mum was wearing a lot of that strong musty-scented felt, because it was all made of hessian and heavy materials. She looked like a Kabuki figure to me. I looked up at her and I said, “What’s the play called?” And she said, “As You Like It.” I said, “No, seriously, what’s it called?” And she said, “It’s called As You Like It.” I got cross and said, “I’m asking you a serious question.” She said, “That’s what the play is called, As You Like It.” I realized later on how clever Shakespeare had been with titles like that or What You Will, that he was actually saying, “Look, make of this what you will, kid.” But going backstage was the most thrilling thing, because even though we were children, the actors were so open. I remember the actor playing Bottom once opening the dressing room door to me, because my dad had said, “Go and just knock on the door.” You’d open the door and he was absolutely stark naked except for his really interesting black G-string codpiece. I was on an eye level with the codpiece, and I just remember thinking, “How wonderful. They are so free, they don’t mind me seeing his codpiece.” It wasn’t disturbing. Actors were marvelous for us kids, because they were a bit like us.

KUSHNER: It’s a very appealing world for a kid because it erases some of the distance between childhood and adulthood.

THOMPSON: It’s like when people ask me about methodology. All I say is, “The nearest thing I can liken acting to is a child’s game.” A child’s game is a game, but once you’ve decided you’re the Emperor of China, that’s what you are for that short period of time. It doesn’t require anything further than just to announce it.

KUSHNER: Is your daughter Gaia interested in acting?

THOMPSON: I’m afraid so. She’ll do it for as long as she wants, and then she might get bored and do something else. She’s a very good cook, so she could run a restaurant as well, which I’m quietly hoping for.

KUSHNER: I think running a restaurant is one of the few things that’s maybe harder and more soul-crushing than working in showbiz.

THOMPSON: That’s true. Why would I wish that upon her? You’re absolutely right.

KUSHNER: I sometimes wonder if acting is an inherited ability. You say you didn’t have any specific training or a methodology. Do you think there’s something inherited about that talent?

THOMPSON: I think that there is an inheritable quality to it somewhere. But then again, I’m just having a memory now of being in that big room when we did the read-through for Angels in America with you and Mike. My god, that was such an extraordinary experience, because with acting, once you start saying the words, you just feel transported into a completely other place. Words make you into something else. Acting is a combination of so many different art forms.

KUSHNER: It’s writing and directing and movement. Porousness is an interesting way to think about it also. It’s a capacity for relating to people in a porous way, imagining yourself as somebody else, but also somehow letting in all those people watching you. Does writing come to you the same way acting does?

THOMPSON: Recently, I’ve been offered much more interesting roles, those big old Grand Guignol–type things that use up every bit of me. I love doing that, but I can only do it so often and then I have to rest. But writing is not restful either. I have to make myself sit down and do it. The impetus to do it is because you want something to have a very particular tone and you just need to get in there and do it yourself. Have you ever had that experience where someone’s taken something you’ve written and given it such a different soul?

KUSHNER: I’ve never not had that experience. Mike’s version of Angels is very much Mike’s film, and I love what he did with it. But then you have the very unpleasant experience when somebody does that and turns it into something you really want to disown. I trained as a theater director, and there’s always a fantasy of jumping in and directing it the way I want it. But I’ve always hesitated. I remember the last stage appearance I saw you in was as Mrs. Lovett [in Sweeney Todd] with nothing but a music stand and the New York Philharmonic, and you hadn’t done theater before that in 25 years. You must get offered stage roles all the time. Is there a reason you’ve chosen film over theater?

THOMPSON: I think it’s a weirdly practical thing for me. This is going to sound so fucking shallow, but I’m a morning person. In the evenings, I just want to sit down. I don’t want to get my dander up. Some people I worked with in the theater, they love that, they can manage it, they can do it. God, I just remembered I actually had a theater dream last night. I had a lovely dressing room and I knew what my costume was, I just didn’t know any of my lines. Then I looked through the whole play and I couldn’t find my part or any of my lines. But I thought, “I know I’m in this and I’ve got quite a big role to play. What the fuck? What do I do? It’s about to begin!” Then I woke up. [Laughs] But when I was in my early 20s, I did 15 months of Me and My Girl, eight shows a week, and I’ve got a feeling it might have actually damaged me. I’m not being entirely flippant. I remember having a long conversation years ago with Maggie Smith, who was put into plays when she was young. She would have to do the play for two years without a break. She said it really messed with her head. Yet, you think about the old theater people, they would do the same thing three to five times a day for seven years on end. I’m not lazy, but I find getting adrenalized in the evening quite hard.

KUSHNER: That’s a very profound truth about night people and day people. Steven Spielberg told me he was coming into a building in the early evening when Elaine May was walking out to get into her limousine. She was doing The Waverly Gallery. And he said to her, “Elaine, are you having fun?” She looked at him and she goes, “Fun is what I’m not having.”

THOMPSON: That’s true about film as well as theater! Everybody thinks you’re having this marvelous, glamorous life. The glamour attached to film has now, in my view, attached itself to those endless bloody awards ceremonies that go on forever. It’s gotten out of control. If you’re on some sort of awards circuit, you spend three months of your life trying to think about what to wear to the next ceremony. This past year has been a nice break from all that. Frankly, I thought it made the whole profession look idiotic, not glamorous, because we felt like a bunch of performing ponies wandering up red carpet after blue carpet after whatever color the carpet was. It became ridiculous, and I think there’s a good change to come in that department.

KUSHNER: It’s silly to complain because people have fantasies about what it must be like. But the few times that it’s happened with me—and as a screenwriter, I can show up in a potato sack and no one would care—going to those parties, there’s a static of nastiness surrounding the whole thing and people sniping at each other. By the end, you really feel like you’ve done something bad and you’re being punished for it. But perhaps, amid all the lament about movies not being in movie theaters anymore, there’s at least some possibility with these streaming services that we’ll never know how much money a film is making and we’ll be free from that horrible horse race of the opening weekend.

THOMPSON: I remember when we were opening Primary Colors at Cannes in ’98 and there’s that huge room where they do the big press conference at the beginning of the festival. We all sat down—me and [John] Travolta and Elaine May and Mike and everyone. We were really excited to be there. The mediator took the first question and it was about the box office, and there was a long pause and Mike just said, “I have such a happy memory of coming to Cannes when people wanted to talk about the movie.”

KUSHNER: Primary Colors is one of my favorite performances of yours. And it’s one of my favorite movies of Mike’s. It’s a terrifying and brilliant analysis of the terrible risks of being a politician. The Russell T Davies show you recently did, Years and Years, also drove me into a block of depression. I adored it completely. Trump was already president when it was made, but there’s a way that the series feels like a warning to all of us that we were about to enter this complete nightmare of a year. It’s a little bit like what [Robert] Altman did in Nashville. Your character, the MP Vivienne Rook, isn’t Trump. She’s much smarter than Trump. And she’s not Thatcher. She’s much more politically indeterminate than Thatcher. You’re one of those actors that everyone looks forward to seeing in a movie. Here was Emma Thompson, who was so awesome in Remains of the Day and Howards End, where you play voices of reason and decency, and now you’re playing the devil.

THOMPSON: She was such a wonderful thing to play. Russell T Davies is amazing, and the show was so prophetic. When we were shooting it, we were frightened. We, the actors, kept saying, “This is scaring me.” I found it hard to sleep at night. The fact that you see this person, and you can see where it’s all coming from, but then you don’t see the fact that she’s been swallowed up and manipulated—it reminds me of learning, years and years ago, that it doesn’t matter who is leading the government, money will always be in control. Unfortunately, that pertains more and more. And yet, we’re in our 60s and young people, even though they’ve been through this terrible year, don’t seem to be as depressed!

KUSHNER: I think that’s because recent generations really seem to have gotten the beat on exactly what you’re saying, that you can’t have social justice without economic justice. In a way, you can get a semblance of social justice, a window-dressing version of it, and still have the most profound economic barbarism shattering the lives of the vast majority of people on the planet. These young people are really calling us on that. Of course, I’m an old man now and young people are always hateful and annoying in a way. But I’m still impressed by how absolutely serious they are that we’ve got to make changes.

THOMPSON: We’ve fucked up their planet completely.

KUSHNER: One of the terrifying things about Years and Years is that it went a tiny bit ahead into the future, taking all the worst possible outcomes of everything we’re facing and saying, “What if all those things that keep us awake at night come true? Is it going to be as bad as we think it is?” And the answer the show provides is, “Yes.” You’ve always been an activist, and you’ve always been outspoken. Do you feel any hope?

THOMPSON: I think there is now a generation of people who are ready to say, “Okay, we really do need to change the system. Capitalism is not serving anyone except very, very rich people in a very particular layer of society. This system is over. It’s not going to survive, it can’t survive. Because if it survives, it will take us all down with it.”

KUSHNER: It really is change or die.

THOMPSON: There isn’t any other choice.

KUSHNER: In all this seriousness, I still haven’t asked you anything about Cruella. You play a character called Baroness.

THOMPSON: All I can say is that I have never had underwear like that. I had underwear like a ship’s rigging, it was just extraordinary. In the end, I had to stop drinking anything, because just to take a pee was an enormous ordeal. I would turn up to the set in a six-foot wig, a massive costume, and heels, with three Dalmatians on leashes. Dalmatians are tricky customers, let me tell you.

KUSHNER: They’re not very bright.

THOMPSON: No. But these Dalmatians did well, although they nearly killed me. I definitely channeled some sort of inner Cleopatra. I’ve never played anyone like that before and I just kept pouting.

KUSHNER: I can’t wait to see your pout.

THOMPSON: I pouted my way through that movie like a fucking puffer fish.

———

Production: Elise Lebrun at April Production

Photography Assistant: Ed Aked