IN CONVERSATION

“More Is More”: Photographer Elizaveta Porodina Reimagines the New York City Ballet

If there’s one rule photographer Elizaveta Porodina follows religiously, it’s that there’s no such thing as too much. “More is more is a good thing, not a bad thing,” she told costume designer Mati Hays, with whom she collaborated on the New York City Ballet’s latest commission. As they sat down last week to assess the work in person, the two reminisced on a month of sleepless nights and elaborate costumes. The exhibition, on display at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center through March 2nd, showcases the company’s dancers at their most free—and unrecognizable. Porodina, a Munich-based photographer whose work has been featured in Vogue, GQ, and Vanity Fair, renders the ballerinas as avatars of the future, some posing as gladiators and others as jesters, abandoning their usual precision. To mark the unveiling, she and Hays got together to talk about the life cycle of a ballerina and the art of not taking yourself too seriously.—ARY RUSSELL

———

MATI HAYS: Let’s look at these new images. They had three releases of the images that we did, so I’ve been looking forward to seeing what actually comes out.

ELIZAVETA PORODINA: You’re luckier than me because the last time I was here we shot the images together, and I never managed to come back. I always hoped that I would see it live, that I would go to the ballet and we would celebrate with champagne, but then I never could. You told me that your friends and your colleagues and people you’ve never met received them in the mail and I was very jelly.

HAYS: Yeah, I was wondering if they were going to ship to Europe or not.

PORODINA: They did, but it’s not the same as celebrating with everyone.

HAYS: Yeah. People here have been recently sending me videos of the advertisements in the subway, which is incredible.

PORODINA: That’s what is so special about working for such an iconic institution. The work continues to live on and people get to experience the work in places like the New York subway, or the facade of the ballet. It’s so special, it’s almost like taking part in an iconic movie.

HAYS: Exactly. The planning of this was also like a movie. I was thinking about how I created boards for the project and presented them to the creative team, and they were like, “Wow, we’ve never seen this before.” And I was like, “Wait, what?”

PORODINA: These were the most eloquent boards for me as well. They were incredibly detailed.

HAYS: Thinking back on it, I was like, “How were those organized?” It was really so detailed for a storyboard of how I would costume a movie.

PORODINA: Absolutely.

HAYS: But I never thought about it. I just did it.

PORODINA: That’s how it felt for me as well, that your role was way more about shaping characters and dressing narratives. It requires planning, but also a spontaneous reaction to the person when they’re standing in front of you, with the triumphant results of their work on themselves and together with each other. It was so impressive seeing them for the first time, the way they look, how they use their bodies as an instrument. I had a newfound respect for you for doing something so different.

HAYS: Totally. It wasn’t like any of our original ideas were gone, it was more, “Let’s elevate this to a whole other level.” Because I had not really understood how much they would be dancing. I thought it was more posturing in their positions, but it really was full-on dancing.

PORODINA: Yeah.

HAYS: That’s what changed a lot of my perspective, that the caricatures were created because I actually got to experience how each of them individually wanted to dance. Each outfit also influenced the choreographers because when the dancers would come out, they’d be like, “Oh, we need to go here.” Pointing to specific dances, specific theater plays, choreographers, that kind of thing.

PORODINA: That’s also what happened with hair and makeup, that everyone was challenged in the best way by each other’s team because they would come out of the makeup and it would be a full-on creation, and obviously the costumes have to live by that.

HAYS: I didn’t know how your process actually worked. So being on set and seeing those first pictures being taken, I was like, “Oh, wow, this is a whole operation and you’re able to see the actual image that’s coming out as it’s coming out.” So those details that I was spending hours and hours on were blown out. It was a different color, but it was exciting because suddenly there’s more abstraction and room to play.

PORODINA: Working with the dancers, were you challenged by how different they are in their own self-expression, or is that normal for you?

HAYS: When I work with stage performers, what I like to best capture is themselves in the most vibrant and expressive way that they could possibly imagine. But what I really wanted to capture with individuals and the ballet as a whole institution was that there’s a regimen, and everyone has their own idea of what it should look like. I thought about the hard life that ballet dancers experience for a certain amount of time. It’s relatively short-term for their bodies. I thought about how young a lot of them are, and that the oldest here is barely 40.

PORODINA: 39.

HAYS: Exactly, and we had as young as 17. So I really loved the idea of bringing out the youth of the individuals instead of the staunchness that is projected on them by the history of what an older generation wants to see out of the ballet. Like she [Olivia Bell], was the youngest, and that was the Betsy Johnson look.

PORODINA: Absolutely.

HAYS: I had the hair and makeup changed to be a little bit more sparkly and silver. The Betsy Johnson punk was what I wanted to bring into her because she was so young. And we played Azealia Banks while she was performing and it was super, super fun.

PORODINA: And Beyonce, too.

HAYS: Yeah. Individually, we got to play the music that each person represented.

PORODINA: Yeah. I totally read the vibrance and the contemporary elements, but I also read what you were saying about the element of struggle and the necessary resilience that always comes with labor. I guess when you really dedicate yourself to something bigger than yourself, a collective effort, there is always an amount of suffering, and I see that in the costumes as well. But what you were saying about the youth and the vibrancy and the short-lived thing reminds me of courses of nature, which is very timeless in itself. Like a praying mantis only lives a year, but it’s the most beautiful, the most ferocious, the most vibrant, the most unique being on Earth. And I see that in the costumes, from the colors that are directly inspired. It’s as beautiful as a sunset, and there is nothing kitsch about it. It is just incredible.

HAYS: That’s where we connect, the color. But I work directly off of color and material, so it’s not really about the muse or about a personality so much. I’m first inspired by color and material and then I move onto the person. But you’re able to connect and disconnect the color because you can change to anything you want. I can’t even imagine the editing process.

PORODINA: But I think the way you connect with the color is very intuitive. I guess you can’t explain why you like chartreuse or whatever, you just feel it, right? It has a certain power for you, so you hold it as a talisman and then you wrap your concepts around the feeling. And in the same way, when I edit, the intuition is what leads me and not some sort of bullshit that I tell myself. Because the possibilities are infinite, so you could really go in any direction.

HAYS: I don’t want your job. There’s no way I could have edited this fabulous exhibition because the way you can do color is infinite, as you said.

PORODINA: Do you ever get stuck? Do you ever have a mental block? It’s very hard for me to imagine that you do.

HAYS: There’s a lot of ways you can get stuck. There’s a lot going on in the world that can interfere with the free mind. But within a singular process, where I would get stuck is in the edit, because I’m a “more is more” person. And when you’re dealing with clients, they have a specific vision that they have to execute.

PORODINA: I realized, naturally, I would never have a creative block because I’m capable of not pushing it when it’s not needed. If it’s not coming to me, I just get up, go eat something, get fresh air, go to a museum and then it will come naturally. It always does. The issue is when people start pushing you in directions where it doesn’t belong. And I feel like that’s the good thing about this project, no one was doing that to us. It was a full-on carte blanche, and we could just do what we wanted and how we felt it. Because so many factors were changing and fluid with all the movements, with so many different people. And the way the clothes react to the light, there’s already so much. Imagine if someone was like, “Can we see options for that?”

HAYS: [Laughs] That would be my reaction, hysteric laughter.

PORODINA: Instead we got this amazing collaboration with the team from the ballet who were incredibly supportive. And then we had Wendy [Whelan] and Craig [Hall] on our side who were the best collaborators, because they were really looking at what we’re doing and pulled things out of their memories that fit the direction, which felt like such a luxury.

HAYS: When I brought out one of the dancers and we put the latex gloves on her on set with the lube on her hands, everybody was like, “Is she okay?” But when we brought her out and she was wearing black and red tights, red shoes, and a custom chartreuse top, that’s when she went right onto the set, and the choreographers looked at me and they were like, “Let’s go Fosse.”

PORODINA: Yes, Fosse.

HAYS: So she did a whole Fosse routine, and that made me really, really happy.

PORODINA: To me, it’s about eclecticism and not taking yourself too seriously and understanding what is beautiful about camp. And that “more is more” is a good thing, not a bad thing.

HAYS: That’s where we totally had to take it.

PORODINA: Yeah. It almost seems like the institution of ballet is so respected and shielded and so feared that no one wants to touch it in this way. But it has to live on because of all the elements that you mentioned; the extreme dedication, the discipline. These are all things that I admire, but that’s why you need to see it from different directions.

HAYS: Yeah. I would see it as if almost any one of these dancers would have put on those clothes on their own to go on a night out. That’s kind of how I imagined it.

PORODINA: Do you have a favorite where you’re like, “Wow, this is exactly what I wanted?”

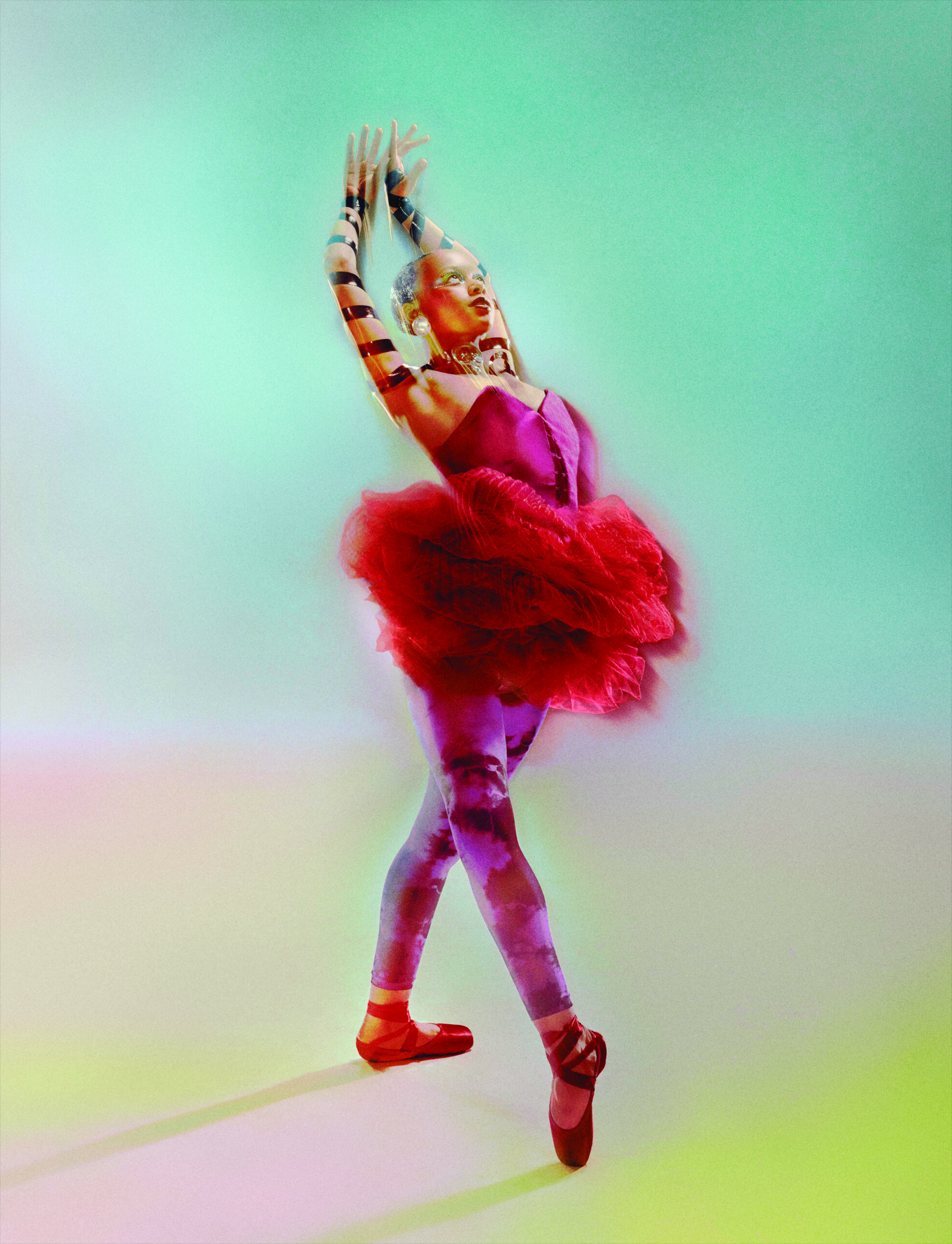

HAYS: I think always the three girls, that was a moment that we were all like, “Okay, this is it.” Those colors that all combined with each other, those were great. India [Bradley] was so fun. I put a tutu on her back that was made out of real blue tulle.

PORODINA: Yeah, the color combination is so scrumptious.

HAYS: And then Megan [Fairchild] was fun. I put a skirt on as a dress that had kind of a tulip feel that had red underneath the bottom, so we kind of did a can-can girl with her. That really turned out well with the hair and makeup as well.

PORODINA: It was amazing to work with her because we really got a chance to connect, and just hearing about her life, I was just so fucking impressed. She has two MBAs and five children.

HAYS: Yeah.

PORODINA: And very casually, without bragging or anything, she talked about her many injuries and how much she has invested in this career and how grateful she is. It didn’t even seem like an effort, but this is how you know how much work someone has put in, when it seems so simple. Just from artists to artists, when you see someone execute their discipline, that is so impressive to me. And having this natural effortlessness because they didn’t have the chance to think about it too much yet they’re just naturally beautiful. And not even having their routine, but just going into it and interpreting it to contemporary music.

HAYS: Can you pick a favorite?

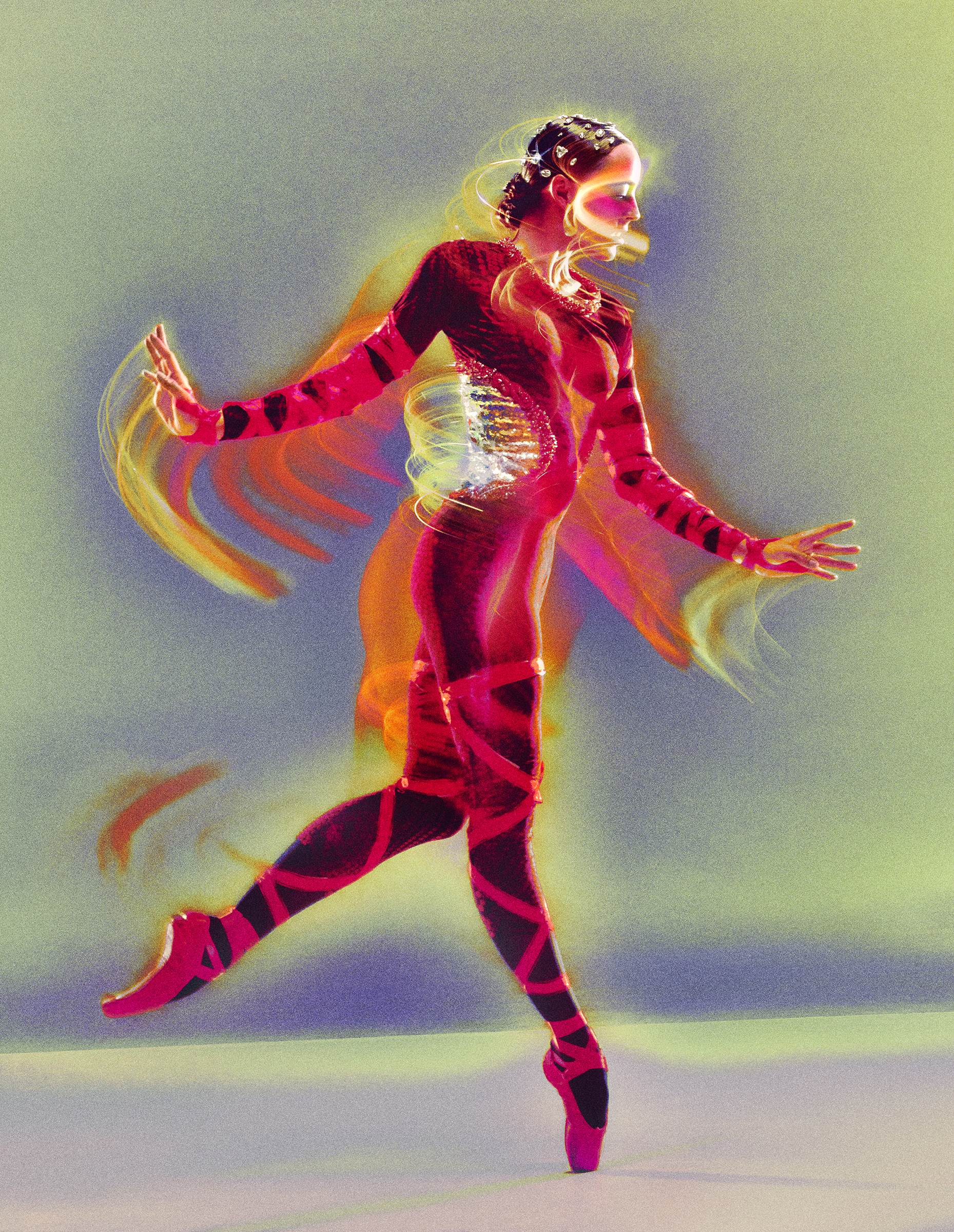

PORODINA: No, I can’t. Because I worked on them for such a long time and I touched every single image so many times to bring it to perfection. There were certain times where I felt like, “This has worked out exactly the way I pictured it.” For example, the series with Emily Kikta with the old red outfit where every single movement is perfectly tracked by the exposure of the sparkles, that was exactly what I had in mind.

HAYS: I feel like from when we first started working together with the boards and the ideas and concepts we executed, I walked away from the two days of shooting being like, “We executed exactly what we were going for,” which you don’t always expect. It was just like the subconscious kind of dialed in and then checked everything off of the boxes.

PORODINA: But I remember how you assembled every single outfit from every single vintage store and every single material that you could find, just sewing through the nights.

HAYS: Oh, yes. One month to do 18 looks.

PORODINA: You still have some of the pieces, right?

HAYS: Yes.

PORODINA: And some are gone?

HAYS: Yeah. I had to get rid of a couple of them, but I still have the to and fro of exactly what I wanted this to look like.

PORODINA: For the history.

HAYS: Yeah, I didn’t know if I was going to wear one of them today or wear one on Friday, or maybe one of the next weekends I might put one on.

PORODINA: Yes.

HAYS: Have you shot any other dancers since?

PORODINA: Not ballet, but I did shoot quite a lot. A couple of people who dance with discipline of Gaga and Butoh and things like that. So more interpretive, non-traditional stuff. It’s always fun to shoot dancers. It’s a different beast from casting talent or models. When you’re shooting a classic model, it’s almost kind of expected for you to bring this entire story and give a lot of direction. But with a dancer, there is a big, almost like Rolodex of specific moves. You have to make the decision. Do you want to rely on them and sort of show this classic control thing, or will you have to break this form and try to find what is underneath? How comfortable or uncomfortable will it be for them? I remember actually very distinctly that here it was the same dilemma and the same idea, because you want to show the form that is executed here at the ballet in perfection, but you also want to show something that will emotionally ring true, that not only will say, “Oh, beautiful,” or. “Wow, perfectly executed,” but also, “Oh my God, it makes me feel something.” And I feel like sometimes unexpected music will provoke unexpected movement.

HAYS: Is music important for your process?

PORODINA: No, it really isn’t. I wish I could say, “Yeah, I have a specific playlist.” I have a terrible playlist. It’s eclectic in all the bad ways.

HAYS: You need kind of the medication of music to just get through it.

PORODINA: No, I wouldn’t even notice if there was no music played, because in my head it’s just so loud. Is it important in your process?

HAYS: Yeah. I move through motions of music, so kind of my entire process is led by the moment of where I am. I don’t remember where I was when I was doing this. I’d have to look back because we shot this in October of ’23.

PORODINA: I think we were always trying to play what is appropriate for every specific image.

HAYS: But were you choosing the music? Because it was great.

PORODINA: I hope not. Imagine me just playing JoJo Siwa three times in the row.