Edwige of Le Palace

the essence of life was brewing in that club, from the ultimately famous to the completely unknown discovering each other. Artists would find inspiration, designers would find ideas or new faces and styles, anyone could find love, for a night or a lifetime.Edwige

We asked Olivier Zahm, the editor of Purple Fashion magazine, to interview Edwige, who, as gatekeeper of the legendary Le Palace, was the queen of Parisian nightlife in the late ’70s. Le Palace was to France what Studio 54 was to America, and Edwige created the nightly mix of people that made for a fabulous party. When she came to New York City in the late ‘70s, she quickly fit into the downtown scene—hosting, performing, and then eventually teaching yoga. Today she has an utterly fierce style all her own.

OLIVIER ZAHM: Do you love your name? It’s derived from a German word for war. Does that describe you in a way?

EDWIGE: I love my name, I was named after the beautiful French actress Edwige Feuillère. I don’t really see myself as a warrior. I feel I floated through life; sometimes I hate the idea of not having fought more. Still, I won a few battles . . .

OZ: How did you become an icon of the underground in Paris in the ’70s?

E: Meeting Serge Krüger and his group of friends was definitely a door opening and a massive life change. Philippe Morillon, the painter and photographer, worked with Andy [Warhol], and we were going to Club Sept, owned by Fabrice Emaer, where I got introduced to the fabu-lous Parisian gay scene. I was 19. Then I met Andy, Helmut Newton, Grace Jones, Paloma Picasso, my sweet Loulou de la Falaise … I mean, the list is endless, since at the time, fashion, music, dance, and art icons were out and partying in a less paparazzi-infested world. They all could actually have fun. Being at Club Sept was like being at Fabrice’s home. Paris was exploding in those years-fashion was changing, new designers, new styles, disco, punk …

OZ: How would you describe your life in Paris in the years ’75, ’76, and ’77?

E: Those are three totally different years for me, so it’s hard to mix them up. Edwige really started existing as we know her in ’76—when I shaved my hair, burned my clothes, and only wore riding pants, button-down shirts, skinny ties, high heels, and a leather jacket Serge had given me. That was my only outfit. The people I met created the revolutions in fashion, music, art, and style. I wasn’t really sure of what was happening around me at the time. I barely knew what was happening to me.

OZ: Without being nostalgic, what is it that you miss about those Parisian years?

E: Without nostalgia, are you kidding? It is really the fact that it felt like the beginning of an era, the birth of a movement. And, of course, I miss my Solex Moped.

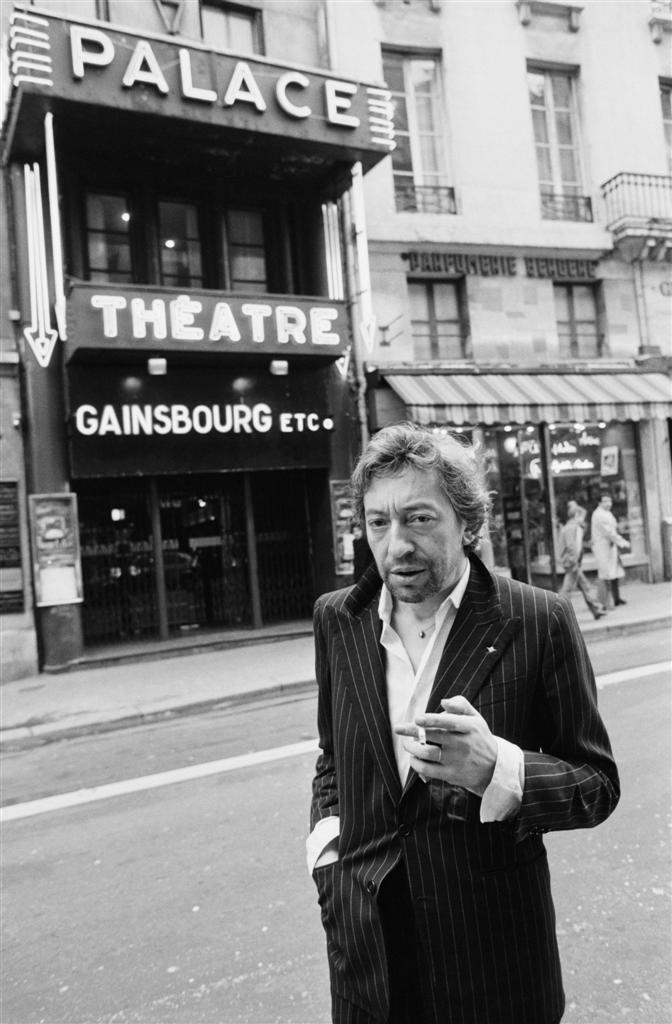

OZ: Talk about Le Palace. Your name is a big part of its myth.

E: I had met Fabrice at Club Sept. He called me his adopted daughter. He gave me the keys of the club to come practice during the day with my band Mathématiques Modernes for our first single, “Disco Rough.” Then he told me he was opening a new place and asked if I’d be interested in working the door. The new club was Le Palace. It was the fall of 1977, and I’d hung around enough that I knew everybody who was family to him. So I said, “Okay!” I felt more like a mascot than anything else, and that was all right with me. I was on top of the world. I loved them, and they loved me. The renovations of the place were so exciting—Fabrice Emaer, Sylvie Grumbach, Claude Aurensan, Guy Cuevas the DJ, everyone pitching in. It was a historic moment in the Parisian nightlife-the opening night in March of 1978!

OZ: Tell us about the opening, the Grace Jones concerts, and some of the first parties.

E: The opening is a little blurry for me. I was 20 years old with a power position and six or eight bodyguards. I didn’t see much of what happened inside, but the street was blocked off by people wanting to get in. Being over 6 feet tall and on a step, I could see who was of importance or who was cool—like we said, “It’s not what you wear, it’s how you wear it.” Believe it or not, I might have made that one up! Fabrice told me: “This is our home. Invite in only the people we know or the people you’re comfortable with.” And for some reason I had the knack. People still talk about it today, how special they felt when I picked them, or how good I was at recognizing the elite and parting the peeps sea to make it easier to get in. It was really a matter of feeling. If it is my home, I don’t want to let a tuxedoed asshole in but maybe a sweet kid that looked fierce. Christian Louboutin, for example, was 16 or 17 at the time. He and his little gang soon became part of ours. The first parties were always over-the-top. Loulou and Thadée [Klossowski]’s costume party, Grace’s concert, Prince’s concert, my New Year’s Eve in ’78. It was grand, chic, elegant, decadent, novo, punk de salon-insane by today’s standards. There will never be another Studio 54 or another Le Palace, until Steve Rubell and Fabrice Emaer reincarnate . . .

OZ: Describe a normal evening at Le Palace.

E: To describe an evening is impossible because it was always so unpredictable. Never normal. We didn’t have cell phones but we always managed to stay in contact-one would call another who would call another, etc. Since Le Palace was home, we usually went together at the beginning of my shift. Why waste a minute? Again, I will emphasize the family factor. Everyone working at Le Palace at the time knew each other from Club Sept, the youngsters and the elders. We’d have a bite to eat and run to our nocturnal sanctuary, run around the place for hugs and kisses, and take our respective spot-door, DJ booth, bar, or dance floor. The Privilege became a lesbian night on Sundays in the mid-’80s. It was the beginning of cute lipstick lesbians and still mixing with the older guard. It was great. Fabrice would have loved it . . . but sadly he had passed by then.

OZ: Fabrice Emaer created Le Palace. Tell us about him.

E: I adored Fabrice. He was the god of the Parisian nightlife: grand, generous, and yes, fabulous. It was impossible not to like him, not to love him. Celebrities, gorgeous women, and gorgeous men, straight or gay, lined up to receive a kiss, a glance, a “How are you my bébé?” d’amour.

OZ: Le Palace had such a diverse mixture: straight and gay, young and chic, mixed with old and rich. That was something new. You brewed a strange mix.

E: It is absolutely true; the essence of life was brewing in that club, from the ultimately famous to the completely unknown discovering each other. Artists would find inspiration, designers would find ideas or new faces and styles, anyone could find love, for a night or a lifetime. I remember fondly those who left us. My dear [French DJ and musician Philippe] Krootchey passed away a couple of years ago, and probably many more I wasn’t told about. But as for those who are still around, when we see each other it feels like where we left off. The last time I saw Grace in New York at a club where I had a party, she jumped over the table to hug me. We spent days together after that talking of the old days. I really don’t know what’s going on in the Parisian nightlife nowadays. In New York, Eric Goode and Serge Becker were the only people to re-create that kind of atmosphere, like they did at Area in the ’80s. Suzanne Bartsch still throws a fierce party now and then. These people are my New York family.

OZ: You left Paris for New York, where you joined up with Maripol and her crowd. That must have been an interesting time.

E: When I first arrived in New York, I lived with a friend of my first husband, Jean-Louis Jorge—Jean-Louis had given me a note in English that said: “Please take care of my wife, she’s a good friend.” It was the winter with people skiing down Fifth Avenue, steam gushing out of the ground in the middle of the streets. I was overwhelmed. I had met Maripol in Paris when she hooked up with Edo Bertoglio, the photographer, and they decided to make it in New York. I didn’t really know her, but when I arrived in the Big Apple, I stayed in the Village, and Maripol and Edo lived uptown. I would go visit them and hang out. I didn’t speak English, and they did, and they already knew everyone who one should know in the city, so I was home again. She is still my sister, and we recently became neighbors again. Maripol took me to the Mudd Club downtown. I don’t think I need to talk about my New York cousins. Everyone knows about downtown New York in the ’80s. If you don’t by now, you should be ashamed.

OZ: Did you know Andy Warhol? Was he your gateway to the New York underground?

E: Andy definitely opened doors for me. Or at least my connection to him did. We had a silent connection, obviously because we didn’t speak the same language. I was totally in awe of him, but I played it tough, and he liked that. He brought me to Studio 54 regularly, and I would sit in the little roped-off VIP area by the dance floor next to Halston or Liza Minnelli and dance with Bianca Jagger and fall in love with Patti Hansen, all in a heartbeat.

OZ: After appearing on the cover of Façade with Warhol, you were described as “la reine du punk a Paris.” But in a video interview with Maripol, you said, “Punk is fashion.” It took amazing lucidity to link punk with fashion then, to recognize that it was more than music.

E: This was the way some of us fashion outlaws felt. To be punk in the sense of the term, you do it through your music and your uniform. We’ll do it through our revolutionary style. Punk was a revolution, after all. I was never a punk rocker; I was the Queen of Paris Punk.

OZ: You modeled on the runway for Thierry Mugler and Jean-Paul Gaultier. How was that different from the runway today?

E: The early shows of both Thierry Mugler and Jean-Paul Gaultier were like a punch in the face,

OZ: Did you encounter Yves Saint Laurent-with Loulou de la Falaise, perhaps?

E: Of course I met Yves. While I was working at Le Palace, he heard my birthday was coming up and offered to make me a suit I could wear at work, so Loulou arranged it. I was to design my own tuxedo. Wow! All I wanted then was red tux pants with a satin band on the side and a waist-length white jacket with gold buttons. A couple of fittings later at a Palace party, I was proudly wearing my one-of-a-kind Yves Saint Laurent tuxedo fitted by Loulou herself. Someone broke a glass in my hand and covered my white jacket in blood. How punk was that? I still had the pants a couple of years ago. I passed them on to a dear friend who worshipped them. I still have an Yves Saint Laurent necklace, Loulou gave me that one night in the bathroom of the Club Sept. It has been with me ever since and forever will be.

OZ: You broke a barrier with tattoos. You sported them when they were still rather taboo. Do you still get tattooed?

E: My tattoos are stepping stones in my life-moments, loves, fears, messages. My tattoos expose my heart and my soul and make me stronger. I still cannot hear the buzz of a tattoo needle without wanting one. I will never stop getting tattoos; they are my diary.