Punk Encyclopedia: Destroy All Movies’ Zack Carlson and Bryan Connolly

The new book Destroy All Movies: The Complete Guide to Punks on Film weighs in at 500 pages and documents the appearance of punks, from background extras to Patti Smith, in over 1,000 movies. The tome’s editors and head writers are Zack Carlson, who has been appointed modern-geek royalty as a vocal programmer of Fantastic Fest and Alamo Drafthouse, and Bryan Connolly, one of the driving forces of Vulcan Video in Austin, Texas. Like an algorithm zapped across a smoggy landscape of wastoid cinema and blown-out amps—from the sleaze of 42nd Street to Malcom McLaren’s London—no suspect VHS or DVD was left unturned in the hunt for liberty spikes, rebellious acts, and agape mouths of paled normies. It’s an exercise that may be interpreted as obnoxious, as trivial as the vacant state of punk in 2010. And yet each film is allotted a paragraph to several pages for reviews, supplemental interviews, and analysis that range from wittily divisive (Todd Phillips’s Hated) to impassioned reconsideration (Valley Girl), all written in a fluid, knowledgeable manner and laid out in the clean and smart design expected of Fantagraphics, the book’s publisher. Carlson and Connolly spoke to me about a variety of the book’s punked-out pictures, which date from the mid-’70s through to the chosen cutoff year of 1999.

HUNTER STEPHENSON: What is the earliest film included in the book?

BRYAN CONNOLLY: Well, there are two. One is The Blank Generation, a documentary about CBGBs that features early footage of Talking Heads and The Ramones, but the audio is not the best. And the other one is called Punk Rock, which was essentially a porn film that had a band in it that was kind of punk. The film was called that because the people who made it thought punk would become popular. And then they actually re-released it, taking out all of the sex scenes and inserting footage of weird little bands from New York. Needless to say, it didn’t do very well. [LAUGHS] Both of those were released around ’76. LEFT: A POSTER FOR THE BLANK GENERATION

ZACK CARLSON: What’s funny about Punk Rock is that the guy who made it, even though it was the first narrative punk film in history, he had no interest in the scene or music. He was dating a girl who, at the time, was excited by the idea of going to New York punk clubs, so he was like “Sure, baby!” and he made this low-rent feature. For the book, we interviewed the director Carter Stevens, and he was completely amused that anyone gave a rat’s ass about his movie.

STEPHENSON: Which movies and filmmakers were requisite for the project when compiling contributions from the true New York City underground? LEFT: THRUST IN ME

CARLSON: Richard Hell wrote the book’s intro, and having his input was a really big deal for us. We felt we had to talk to him, because he was there in every aspect of the New York scene: beyond his music with the Voidoids, he was an actor playing punk characters based on himself, he appeared in so many documentaries. He even had a writing credit in the other Blank Generation from 1980. And of course, he was socially involved with many other punk filmmakers at that time. We made sure to speak to Nick Zedd, and include the short films of Richard Kern. Other pivotal artists for that movement would be Eric Mitchell and Susan Seidelman, who made Smithereens. And we were lucky enough to get in touch with many of them; the book would have suffered without them. For instance, Mitchell is not as consistently remembered within this group as others, but we felt it was important to include him because… these are people who occasionally had differing or blurry recollections of the same events and clashing opinions. [LAUGHS] If a reader is looking specifically for New York punk films, I think we have compiled a reasonably strong portrait of that time. And we also hope the book inspires others to explore and write books on underground films from NYC, and ones from foreign countries as well. Since the book was released, people have suggested films that they believe should have been included. And that’s part of the fun.

STEPHENSON: There were a few films that I thought were overlooked, like Stoked: The Rise & Fall of Gator and 24 Hour Party People, but I checked and they were released after ’99. However, one film I was surprised not to see was Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Did you guys consider the punk attributes of Charlie Sheen’s character in that film? LEFT: FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF

CARLSON: That’s funny, because we talked about that very character and scene. We debated it.

CONNOLLY: Yeah, I even went as far as to write a review for Ferris Bueller, and then at the last minute we took it out. In the end, there were no real indicators that Sheen’s character listened to punk music, or was a part of that culture in any way.

CARLSON: Like, his hair’s sticking up, but it’s due to filth and a lack of hygiene. [LAUGHS] We wanted to include him, but it would have opened up the floodgates to endless junkies. Given, he’s a superlative wreck, and the thumbs-up scene is amazing. The two movies we’re catching the most shit about so far for not including are Over the Edge and Alex Cox’s Straight to Hell. People are trying to throw tomatoes at us for leaving ‘em out. [LAUGHS] Look, we love Over the Edge, but we couldn’t justify saying that any of those kids were punk. They were rebellious, but so were kids in the mid-’60s. They were inspiring and really awesome, but they would have been so in 1970, before punk culture moved in. It’s just a great “youth in revolt” movie. Even though the characters listen to the Ramones at one point, most of the time they’re getting stoned, having long hair, listening to Cheap Trick. Which, granted, I totally respect that. But the characters weren’t intended to be punk by the writers or filmmakers. One movie we weren’t sure about was Gremlins, but one of the contributing writers, Simon Czerwinskyi, managed to convince us, against better judgment. His essay on why Gremlins and the gremlins themselves are punk is probably my favorite piece of writing in it.

STEPHENSON: An actor one wouldn’t expect to appear in a book like this, and moreover to have ever starred in a movie as a sire to anarchy—is Jon Cryer. But he’s included for two films, both of which receive positive analysis: Dudes, from director Penelope Spheeris, and 1987’s Hiding Out. What’s up with that? Why was he convincing in these parts? LEFT: HIDING OUT

CARLSON: It’s funny. Everyone thinks of Cryer as Duckie from Pretty in Pink. And his punkness in Hiding Out is arguable, since he disguises himself as a teen with a punk ‘do and enrolls in a high school. But his performance in Dudes is great; the film is the only example of several punk protagonists-as-lead characters in an American film.

I tried to contact him for the book, I bumped into Jon Cryer at a comic-book convention, of all places. But I think I spazzed out too much. I told him I wanted to “include you in this cool book we’re doing! What are the chances of meeting you here?!” and he just kind of ran away from me. [LAUGHS] He’s probably too used to chatting with level-headed people, like Charlie Sheen.

CONNOLLY: I don’t think Cryer was interested in punk when he was younger. These two roles were simply a coincidence. The producers probably went, “We need a misfit, let’s hire that Duckie kid!”

STEPHENSON: I wouldn’t refer to him as the unsung hero of Destroy All Movies, since he’s well-known these days for his roles in Napoleon Dynamite and Lost. But actor Jon Gries is saluted in the book for his roles in two cult classics: Joysticks, perhaps the only film that to ever be deemed “arcade-exploitation,” and 1986’s awesome TerrorVision. Why does Gries destroy? LEFT: JOYSTICKS

CONNOLLY: Jon Gries’s character in Joysticks goes by the name King Vidiot, and in my opinion he is the most grossly incorrect depiction of punk in movie history. It’s so off and loud in the way it’s written and directed. But Jon Gries plays Vidiot so far from any recognizable reality, in the best possible way. He really gave his all, above and beyond the dedication of every Oscar-winning actor ever stuffed into one movie. He jammed the role hard. Watching King Vidiot, all you can think is that not one human being has ever behaved like this. [Ed. note: At one point, he devours a potted plant, and he leads a gang of female punks called “Vidiots” that are inspired by Pac-Man.] And when the movie’s over, life is instantly boring. You only wish there was an entire movie about this character. Gries was the main inspiration for us to watch all of the ridiculous shit when researching this book.

CARLSON: There are scenes in Joysticks where you can tell Gries is genuinely scaring the hell out of other actors. They are freaking out. It’s a must.

STEPHENSON: Insightful analysis is written for both Out of the Blue and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains. Both of these films offer powerful lead performances—far ahead of their time—by female actresses, teenagers playing punks from broken homes and boldly at conflict with society. Which film do you prefer and what is each film’s considerable merit? LEFT: LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, THE FABULOUS STAINS

CARLSON: It’s difficult for me to separate my affection for something from a broad assessment of its value, so Fabulous Stains is my favorite. I get a lot out of it each time I watch it. I don’t go back to Out of the Blue as much, maybe because I’m a wimp and it’s so emotionally destructive. Fabulous Stains is not as realistic, I guess, because it charts the meteoric rise and crash within the course of a week of a teenage band. As far as gender norms, Fabulous Stains goes after punk, because it was so much of a boys’ club at the beginning, like most things, and perhaps it’s ham-fisted in its rah-rah condemnation of that. What’s really interesting about Out of the Blue, I think, is that even if the main character was a boy, the character would still be just as miserable and awkward. Sex isn’t an issue in that film, and a lot of that can be attributed to Linda Manz, an incredible and underrated actress. And the directors of both films, Lou Adler on Stains and Dennis Hopper on Out of the Blue… these were older men and Hollywood professionals, and I appreciate that ambition using really young actresses. They were outsiders who were dedicated to nailing the youth subculture, you don’t see that anymore.

CONNOLLY: Hopper hadn’t made a movie in years at that point, but the relationships between men and women are very complex, there’s a crushing reality in the relationship of Manz’s family. Punk is almost used like a Band-Aid, a way for her to cope. Linda Manz’s character is so aggressively an outsider, whereas Diane Lane in Stains, she wants everyone to come to her. The motivations for these girls getting into punk are vastly different, but the fall into damage is similar.

CONNOLLY: Pretty much, once the ’90s hit the movies with punks in them became abysmal. By then, grandmothers were wearing purple hair and nose rings. Punk had blended into alternative and grunge. And then “mall punk” started happening. LEFT: IDLE HANDS

CARLSON: There’s a horror movie from ’99 called Idle Hands, where The Offspring perform, and that movie we really trashed. Joe’s Apartment, from MTV, is another one, and Pauly Shore’s Bio-Dome. [LAUGHS] We were pretty brash and vicious on most movies from the ‘90s. The makers of Punk Rock Summer Camp, a doc about the Warped Tour, will probably take us to court for what we wrote.

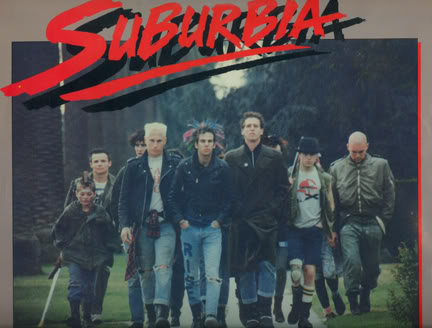

STEPHENSON: If you had to single out one film that best depicts punk, in spirit and all facets, could you choose? A really lengthy argument is made for Repo Man in the book… LEFT: SUBURBIA

CARLSON: We both have the same answer: Penelope Spheeris’s Suburbia. This is actually my favorite film of all time, and it inspired the entire book on the deepest levels. Spheeris wanted to tell a story about believable kids and a horrible struggle, so she cast real kids to play those parts. It’s almost entirely non-actors, and that movie is the wildest for me. Punk or not, it’s the best movie I ever saw.

CONNOLLY: I feel the same way about it, but I also want to include Paul Morrissey’s film Madame Wang’s, which is currently not available on DVD in this country. Sadly. I think it’s his finest work. It’s a great film, a comedy about an East German spy infiltrating the L.A. punk scene in ’80 or ’81, and it captures the moment perfectly but in an over the top way. I encourage readers of Interview to seek it out.

DESTROY ALL MOVIES: THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO PUNKS ON FILM IS OUT NOW FROM FANTAGRAPHICS. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE BOOK TOUR AND SPECIAL SCREENINGS, VISIT PUNKSONFILM.COM.