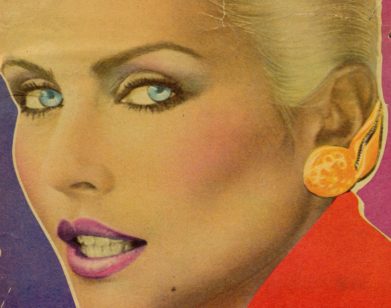

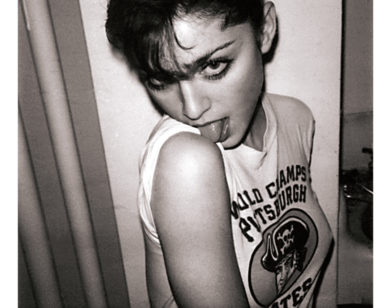

Debbie Harry And Cindy Sherman Compare Notes On Sex, Sexism, and Success

Blazer by VAQUERA.

In 1969, New York City’s Playboy Club catered to an uptown clientele still clinging to a fading midcentury glamor. Years earlier, it was made notorious by Gloria Steinem, who, in an article for Show magazine, exposed its Bunny Manual, a rule book meant to keep its female servers in check. One of those servers was a young woman who commuted to work from downtown, where a cultural revolution was simmering. Her name was Debbie Harry, and at the time, her hair was brown.

As it turns out, rules didn’t suit the New Jersey native well—neither did being a brunette. By the time she formed her new wave band Blondie five years later with the guitarist and her then-boyfriend Chris Stein and the drummer Clem Burke, she had returned to the peroxide shock of hair she first experimented with in high school. Harry, already a fixture in New York’s volcanic punk scene as the lead singer of the short-lived band the Stilettos, brought a pop sensibility—and pop-star looks—to a community that ran on anti-establishment fumes. With their front woman’s effortless glam and blazing stage presence, Blondie quickly distinguished itself from the lineup of snarling young men who owned the stage at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City. Their first two albums, Blondie (1976) and Plastic Letters (1977), brought them attention, but it was Parallel Lines (1978) that made them legends. “Heart of Glass,” a song that sprinkled the Bowery with Studio 54 glitter, transformed Harry into a disco icon, and hits like “Call Me” and “Rapture” established her credentials as a crossover sensation.

Following Blondie’s breakup in 1982 (the band reformed in 1997), Harry released five solo albums, became a philanthropist, and launched a film career. But at 74, she is now ready to take stock of the past with the release of Face It, an autobiography that blends interviews with archival material and fan art. As she prepared for the book’s October release this past summer, Harry got on the telephone with her friend, the photographer Cindy Sherman, to discuss how she became one of the most enduring voices in music, one way or another.

———

CINDY SHERMAN: Hi, Debbie! How’s your summer going?

DEBBIE HARRY: Great, I did a mini-tour that went well. The band sounds terrific.

SHERMAN: Do you still garden? For some reason I feel like we’ve talked about gardening before.

HARRY: I struggle because of my work schedule in the summer. I try to get things going in the spring, but I wasn’t really successful this year. It’s such a treat to put something in the ground and have it come up and be beautiful. You’re a much better gardener than I am. Your garden is incredible.

SHERMAN: I mean, I pay people to do it.

HARRY: But you tell them what you want, don’t you?

SHERMAN: Yeah, and I have a lot of vegetables. But then it becomes kind of overwhelming because there’s so much to harvest. And when you harvest it, you have to cook it. So it’s kind of like, “Oh, god,this is so much work.”

HARRY: You should read the book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. It says that our downfall was when we began to farm instead of forage.

SHERMAN: I’m going to write that down. Speaking of books, you’re now promoting yours. Was writing a memoir something you had thought about doing for a long time?

HARRY: I thought about doing it for a while, and it took a couple of years to actually put it all together. Initially, I was doing long interviews with Sylvie Simmons, who was Leonard Cohen’s biographer, but she had an accident in Tucson, Arizona, and seriously hurt her arm.

Coat by DIOR.

SHERMAN: Oh, no.

HARRY: So we had to stop for a while, but then we got back into it, putting all the pieces together and filling it out. That’s the way to go if you’re not a writer. Sitting down to the dreaded blank page can be horrifying.

SHERMAN: Were there any similarities between writing your memoir and writing songs?

HARRY: With lyrics, I have a basic idea, and then I write little phrases that fit with the music and encapsulate a feeling. I start with a theme and then try to adjust it to the music. I like the music to come first. For the book, I would sit down and tell the story, and then go back and edit myself. It’s probably a similar process to what you do with your photography. You shoot it, and then go back to it.

SHERMAN: I shoot a ton of stuff, and then I find a couple of things that work. There’s definitely heavy editing going on. When you were growing up, did you know that you wanted to be a singer?

HARRY: Yes, although it’s kind of odd. I was shy about performing, but had a tremendous drive, or need, to do it. I am not a natural performer. It really was CBGB and those little bars and getting up in front of a crowd. There are times I would get up onstage—god forbid I smoked any pot—I would be so self conscious. It was painful! But I wanted to do it for some bizarre reason. I had an obsession to find that part of myself, and to learn how to perform. It‘s taken a long time, but I think I finally nailed it. I’ve read that a lot of actors and performers were shy as children.

SHERMAN: I’ve heard that, too. But actors can get into character so they don’t have to reveal themselves. When you’re onstage, are you playing a character? I read on your Wikipedia page that a lot of people thought you were called Blondie, or Debbie Blondie, so there was a sense that your stage persona was separate from you. Did you need that to get onstage in front of thousands of people?

HARRY: I did in the beginning. It helped me to cultivate some kind of female persona. I took a lot of different aspects of my character from my childhood or young-womanhood and elaborated on them. The guys were also writing songs, and I felt like I had to portray what they were writing and appreciate the male point of view as well as the female point of view. I don’t know if it came off that way, but that’s what helped me get up and do it. I don’t know if anybody can get onstage and totally be themselves, except for stand-up comics. What about your characters? It’s obvious you’re portraying specific women.

Jacket by BALENCIAGA. Pants Debbie’s Own.

SHERMAN: Yeah, but it’s easier because I do it in the privacy of my studio. I have a really hard time if I’m asked to introduce somebody onstage, or if I get an award. I get up there, look out into the audience, and just say, “Thank you,” and go sit down. Did you feel like you wanted to subvert men’s expectations of what some hot little sexy singer was going to be? Is that what made you tougher? Or maybe it wasn’t an issue for you at all.

HARRY: I felt like I should use every edge that I could find. Compared to what’s gone on in the industry since I started—I got criticized for showing my underpants.

SHERMAN: So risqué!

HARRY: And flashing beaver is nothing now, so what the fuck?

SHERMAN: What are your thoughts on sexism in the music business? Have you had to deal with a lot of crap from producers or other musicians?

HARRY: Back then it was probably more severe than it is today. I think men are a bit more cautious about their intentions or of expressing their lascivious nature. But also, I operated as a couple with Chris [Stein], so people were a bit more respectful because I was there with my partner. It wasn’t like I was this little chick walking into a studio or an office looking for a record deal. So I never really confronted that. And it has improved. I think it’s hormones and we’re animals. That’s what it comes down to. Is this a decent person, or is this someone who can’t get beyond their sexuality? I mean, I love sex, and I think that everybody should have lots of sex, but it has to be mutual.

Dress by 1 MONCLER PIERPAOLO PICCIOLI.

SHERMAN: What is your take on the state of the music business these days? It must be so hard to be starting out, because people don’t buy actual CDs anymore, much less records.

HARRY: They haven’t straightened it all out either, in terms of publishing and royalties. The only people selling product are rappers.

SHERMAN: Oh, really?

HARRY: That’s what I’ve been told. I’m not especially knowledgeable about the industry right now. My manager is on top of all of that.

SHERMAN: Did you feel like you became famous really fast? Suddenly you were successful. Was it something you had to get used to?

HARRY: I think I grew into it. Anybody who starts a band imagines themselves playing arenas. In your mind, you just go right to the top. But it was a very gradual process. It’s a business. I’m sure it was the same for you.

SHERMAN: Yeah, but not many visual artists get recognized on the street. The level of fame is relative. Especially being the front woman of a band, your face is what people associate with Blondie. I’m sure if you just walk downtown, people want your autograph. To me, as an artist, that’s so bizarre. I can’t imagine that kind of recognition.

HARRY: You’re also a chameleon. But in the art world, people do know you.

SHERMAN: But the art world is so small compared to the music world, especially in the middle of the country where people know your hits, of which you’ve had so many. Do you have fans who follow you to every concert, or who show up so regularly that you almost know them or know their name?

HARRY: We have quite a few people who have stuck with us over the years. We have this one Greek fan who works for an airline, so he comes to many shows. We have Australian fans who follow us religiously and come on a whole tour with us. What about the collectors? Would you consider a collector a fan?

SHERMAN:I guess so, because I have a couple of collectors who have over a hundred pieces of mine. Photography is not as expensive as painting. In away, that’s why they can collect more of my work than somebody else’s. But yeah, I don’t really have fans, per se. Did you share any bizarre stories in the book about weird fans?

HARRY: No. I didn’t share a lot of anecdotes like that. It’s more of an arc of me as a kid, stories and memories from that time, which then moves across the history and length of Blondie. I would like to do a book like that but I don’t know if that’s going to happen. You learn a lot about people and who they are by the way they approach you and the way they talk to you.

SHERMAN:Why didn’t you include smaller stories?

HARRY: I’ve never been a diarist. Years ago, I read Shelley Winters’s autobiography and I can’t believe how organized she was. She kept a diary. She would have a date with Frank Sinatra and would write, “Frank and I went out, and we went here and there, and we saw so and so, and we had this much to drink, and we had wonderful steaks.” I wish I had done that. Selfishly, I wanted to have all these moments in my life shape me, but I didn’t necessarily want to share them. And I guess that makes me a nasty bitch.

Coat and sunglasses by SAINT LAURENT BY ANTHONY VACCARELLO.

This article appears in the fall 2019 50th anniversary issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Hair: Evanie Frausto.

Makeup: Michaela Bosch using Chanel.

Fashion Assistant: Fernando Cerezo III.