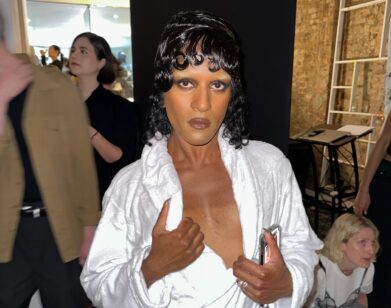

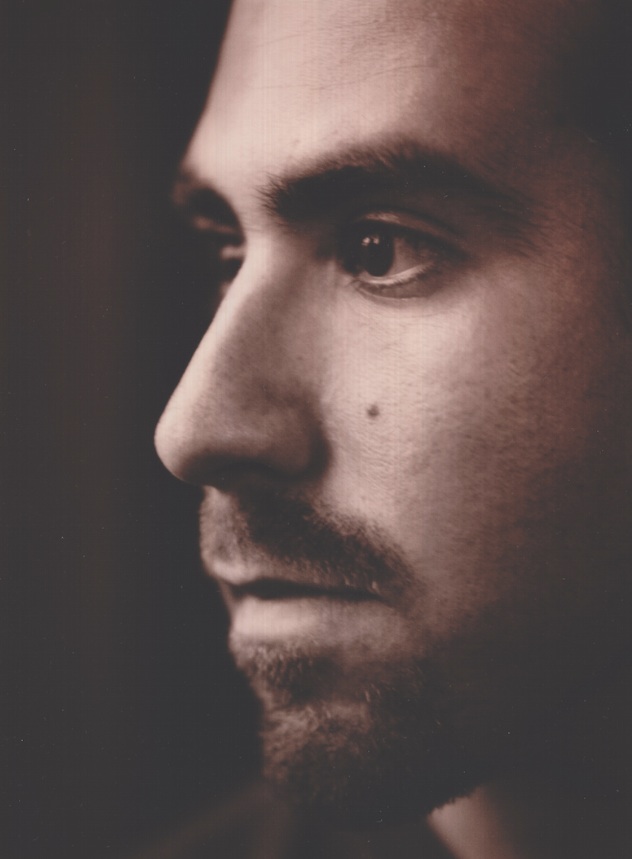

Lively Prose: David Samuel Levinson

A sleepy town, charming on the surface, conceals a nest of vipers in David Samuel Levinson’s novel Antonia Lively Breaks the Silence. Sharpened by plot swerves and an undercurrent of violence, this intelligent psychological thriller exudes the aplomb associated with Patricia Highsmith. Taking center stage are three writers: powerful critic Henry Swallow falls for ingénue Antonia Lively, and haunting them both is a dead novelist, killed under questionable circumstances. Levinson paints a savage portrait of the literary world. These are not soulful artistic types, toiling earnestly away while surviving on organic rice and beans in Bushwick. These are professionals, cool as assassins. Seeking fame at any cost, they have an appetite for sports cars, real estate, and half-million dollar advances. The tale unfolds against a landscape in which the American imagination has gone bankrupt. Levinson’s novelists have lost the ability to make stuff up—they are users, on the prowl for true stories to plunder, feeding off crimes and shameful secrets.

LISA DIERBECK: The book is full of betrayal. Friends stab each other in the back. Do your characters ever make any meaningful human connections?

DAVID SAMUEL LEVINSON: Yes. I saw Antonia and Henry as the big love story in the book. She’s ambitious, but she’s young. She isn’t a horrible monster that’s using Henry. She fell headlong in love with him. The past and her ambition start to collide.

DIERBECK: It’s certainly very sensual.

LEVINSON: It’s an extreme. It’s pure fiction, a work of the imagination, not based on anything real. It looks at the distorting effects of celebrity. It’s exaggerated.

DIERBECK: Is the subject of celebrity familiar to you, close at hand?

LEVINSON: I was going for this simmering that happens around ambition and celebrity. What I’ve seen is that moment when someone awakens. They realize: this person is using me. I’ve never dated a writer. I’ve fantasized about it but never done it.

DIERBECK: What repels you?

LEVINSON: My biggest fear is that I wouldn’t like his work and he wouldn’t like mine. I’ve sworn off showing my work to anyone I date.

DIERBECK: So, what interests you about celebrity?

LEVINSON: We all know people who have celebrity in their own minds. Bret Easton Ellis is one true celebrity in my life.

DIERBECK: He’s been a mentor to you.

LEVINSON: Yes, he’s been very supportive.

DIERBECK: Has his writing influenced yours?

LEVINSON: Strangely, no. We’re polar opposites. He tweeted recently about motivation. What he was saying is, Who gives a fuck? I started the novel 10 years ago, and I was very interested in motivation. In my own motivation for writing it. In my characters’ motivations for writing the books they write. In human motivation—for Catherine renting her cottage to Henry Swallow [an enemy of her dead husband] and putting characters in extreme situations. And seeing what would happen. I do see this book as a novel of manners. All of Bret’s novels are novels of manners. This is where we overlap.

DIERBECK: How do you define a novel of manners?

LEVINSON: In some ways, it’s old-fashioned. It looks at society and the ethics of society.

DIERBECK: Antonia appears to be egomaniacal and disloyal. You show her but don’t judge her. What do you think of her?

LEVINSON: I actually like Antonia. I have a lot of compassion for her. I remember being that age—being a kid and longing to write. But I really think what I wanted was to be heard; I grew up in a family where I wasn’t heard. It’s the same story many of us have. Antonia is just trying to express herself the only way she knows how. What I love about her is she has this very deep sense of morality. This might not come across, but she is very judgmental. She is rash, impulsive. I can’t condone what she does, but she sees it as a moral act.

DIERBECK: How did the book come about?

LEVINSON: I gave it to my roommate in New York City. I was living on Houston and Sullivan, and he gave me the best advice. He said the book was taking place over one and a half years, and that it should take place over one summer, instead. The compression of time changed everything. It gave it momentum. Once I had that direction, I wrote for 12 hours a day for 10 days and came up with the draft that was eventually sold. It hasn’t changed substantially in all that time.

DIERBECK: This is the version you wanted to publish?

LEVINSON: It is. Exactly.

DIERBECK: The town is a character in the book. Do you have strong feelings about that kind of town, a small village?

LEVINSON: I had never lived in a small town or a college town when I wrote the book. Since then, I have lived in two of them. They are pretty much exactly how I imagined them to be. I remember remarking to someone when I first moved to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: “Holy crap, I got it right.” There was even a murder in this town while I was there. It was totally mirroring my book.

DIERBECK: It could be any small town in America.

LEVINSON: I was living in a cottage in a landlady’s house while I was in Austin. She was such a busybody, like Catherine in the book. No smoking. No this, no that. Looking out her window. I missed the anonymity of New York; no one gives a flying fuck what you’re doing in New York. In Austin, if you’re walking anywhere, you’re poor and don’t have a car. I remember calling a friend of mine when I first got there. I said, It’s creepy here, there’s too much silence. It was my first time out of New York in 15 years. I wasn’t used to the suburbs. I was complaining. She said, You should write about this. She’s the reason this book exists. This book is about women, and it’s really for women. I wanted to explore women writers; women writers are always snubbed. I was interested in how men fuck women up and how men get to rise and rise. And they can be as shitty as possible, while women are vilified. I’ve always found it interesting you never hear about a female writer being championed the way male writers are. The men in my book I find particularly vile.

ANTONIA LIVELY BREAKS THE SILENCE IS OUT TODAY.