Dani Shapiro

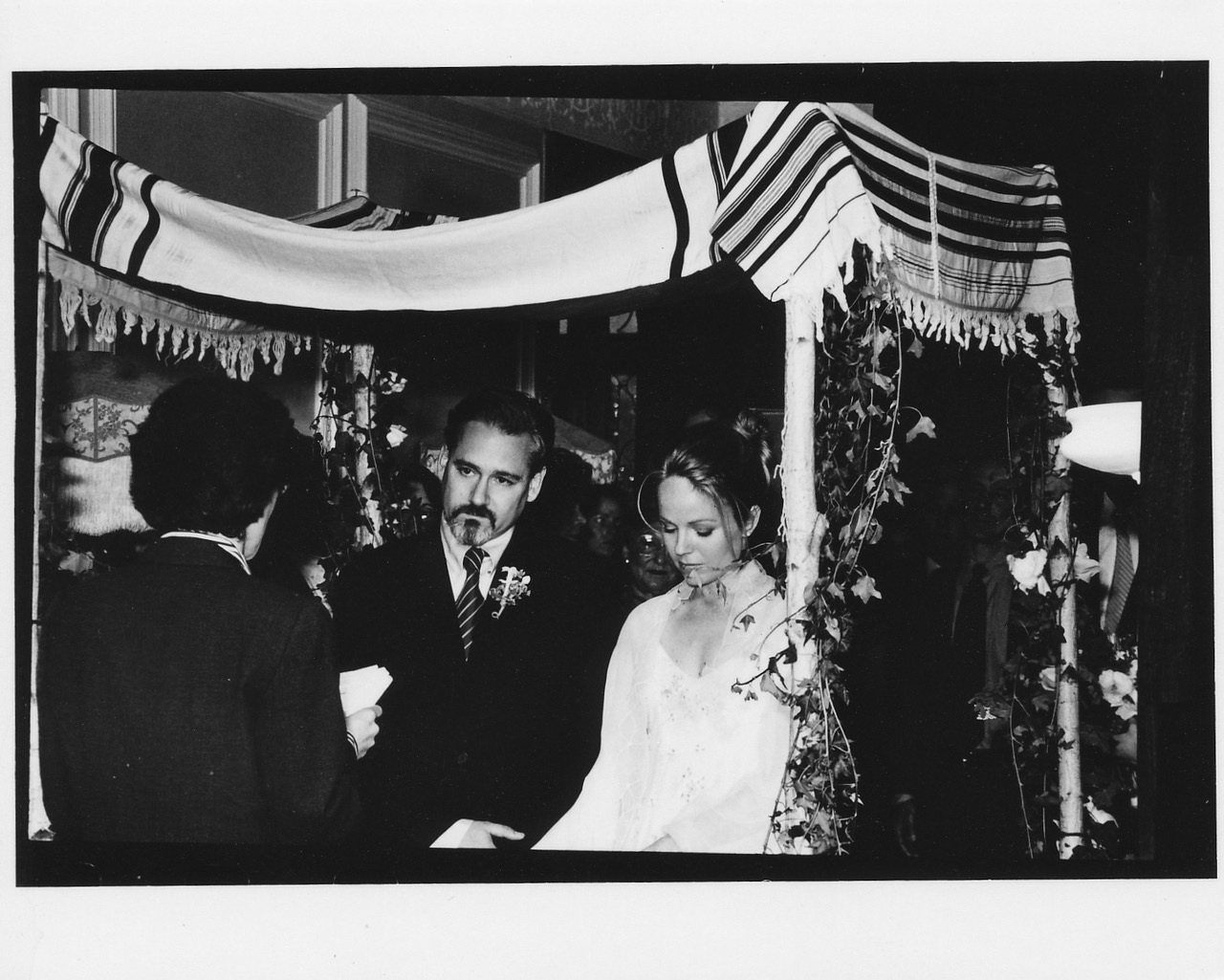

ABOVE: DANI SHAPIRO (RIGHT) AND HER HUSBAND MICHAEL MAREN. PHOTO COURTESY OF DANI SHAPIRO.

In Hourglass (Knopf), out tomorrow, beloved novelist and memoirist Dani Shapiro presents a sharp look at the realities of marriage. She does so in delicate strokes, never seeming self-conscious. With a combination of engaged storytelling and what remains carefully unsaid, Shapiro creates an abstract intimacy that allows the reader into her experience. This slim volume is in keeping with this moment of the distilled narrative, though its author is anything but trendy. It is the very book that should be given to a young couple at the beginning of their relationship.

STEPHANIE LaCAVA: Tell me about the genesis of Hourglass, your new memoir. Your last novel, Black & White, came out in 2007, your second memoir, Devotion, in 2011, and then the instructive hybrid memoir Still Writing in 2013. Where does Hourglass fall in its conception in relation to the other work?

DANI SHAPIRO: As I always do between books, after I finished Still Writing, I kept waiting for the next novel to appear. It had been a really long time since I had written long-form fiction. But instead what appeared was Hourglass. I was shocked by it, really. I thought I was done with memoir.

The way that fiction tends to come to me is with a character or multiple characters who kind of take hold of my imagination and that just wasn’t happening. No fictive world was grabbing me. I’d been wondering for quite some time about this turn that I had made as a writer from considering myself solely a novelist to writing more and more creative nonfiction. When I wrote my first memoir, Slow Motion [1998] I thought that would be it for me as a memoirist. It never occurred to me that I was only at the start of my exploration of the memoir form. I wrote two novels after Slow Motion, and then as I was waiting for the next novel to make itself known to me, instead what began to evolve was Devotion.

After I finished Devotion, I was certain that I would go back to fiction and I actually did try. I got about 100 pages into a new novel and kind of wrote my way into a corner.

LaCAVA: Was this dead end narrative something that relates to Hourglass?

SHAPIRO: In a way. I think the flaw in the novel’s conception was that it was based on a big idea. Big ideas rise from within novels, but I don’t think it tends to be helpful to start with one.

I wanted to tell the story backward in time and there’s a reason why there are very few good novels that have been structured like this. Characters essentially back themselves right out of existence, so, for example, an 11-year-old boy, 15 years earlier, can no longer be a character unless you’re getting metaphysical.

I remember at one point talking to my friend Jennifer Egan who had just written A Visit from the Goon Squad. She asked, “Why does it have to move linearly back in time?” The idea being, if you’re going to upend time, why not really upend it? It was a good point, but by then I had frustrated myself so completely, that I’d put it aside.

Still Writing came out in 2013 and then I was pretty much on the road speaking at universities and to groups of writers. There was a long period of time during which I wasn’t getting much writing done but I was talking about writing, and that was pretty painful.

As I was traveling and giving speeches and teaching, what I was working on whenever I could, and very intensely, was this collage-like essay. The title of it was “The Virtual Dementia Tour” and I thought that it was about time and inheritance. I was very interested in the things that I had inherited from my mother when she died and what I had done with them or not done with them and there was—

LaCAVA: Do you mean actual physical things?

SHAPIRO: Actual physical things. There would be a passage just called Steinway or a passage called Avery or a passage called Nakashima and I was just interested in these objects and the way that they did or didn’t make it into my own world.

This essay took many drafts and many months to finish. When I did finish, I was at this artist’s colony in the swamplands of Florida teaching for three weeks. I had most of the days to myself to write and in this cottage where I was staying there was an infestation of carpenter bees.

These carpenter bees were the bane of my existence. I was terrified of them. I understand that they don’t sting, but they were the size of fists and I was completely trapped in my cottage or so I felt. I finished this essay and I was going to send it to my agent the following day. Then, I woke up the next morning with the entirely miserable thought: “This is not an essay. This is a book. And I’m wrong about what it’s about: It is about time, but it’s not really about inheritance. It’s about marriage.”

So in that isolated cottage surrounded by the carpenter bees, I started to deconstruct the essay, which was excruciating. Of a 25-page essay, perhaps five or six passages ended up remaining. From the start, I intuited that Hourglass was going to be a short book. I wanted it to be able to be read in one breath. I had become increasingly interested—borderline obsessed—with certain writers who I feel have created collage-like narratives so beautifully. Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights would be my model for that kind of book.

LaCAVA: It’s not a new thing, though perhaps a relatively new conversation, playing with hybrid forms, varied lengths.

SHAPIRO: I’m not so interested in what things are called anymore—fiction, creative nonfiction, memoir, lyric essay—except as they relate to the way that the reader reads the book. The reader picks up the book with certain thoughts: “Now I have to suspend my disbelief,” or, “Now I don’t have to suspend my disbelief, because every word is true.” Well, every word is never true. There is artifice and persona in everything.

Which is not to say that I’m never going to write fiction again. I just want to find a way to have it have that same kind of distilled intensity. Certain books come to mind like Susan Minot’s novel Evening, a book that really did that. It’s less about story, and more about entering of a consciousness.

People misunderstand the whole idea of what it means to write multiple memoirs. There can be criticism or confusion because people aren’t comfortable with the idea that you’re figuring something out while you write it. It’s just a form. Readers often misunderstand and confuse memoir with autobiography. The latter is that which presumes the person writing it is of intrinsic interest. And as such, all bets are off and the reader is entitled to know everything about that person because the reason the reader is picking up the book is out of curiosity about that intrinsically interesting person.

But a memoir is story and it’s a story that’s being carved out of a lived life or out of a consciousness that is inclining itself in the direction of memory as opposed to inclining itself in the direction of imagination in which case it would be fiction, but that’s the only real difference.

This may be a little bit of a provocative thing to say, but the memoirist doesn’t owe the reader anything other than a good story and the inclining of the mind in the direction of memory. Of course, the memoirist is not allowed to make things up. But the really skilled memoirist knows what to leave in and what to leave out to serve the story. In autobiography you can’t do that.

LaCAVA: And as a memoirist you can really play with that, even more so when you work with creating a short book that acts as distillation of consciousness, in a way an abstraction. It’s as much what is between the lines, for lack of a better phrase, as what is written.

SHAPIRO: I’m sure I drove my publisher crazy asking to see version after version until the final typeset pages, because any discrepancy in white space would have made me insane.

The white space itself is almost is a character. It’s where the reader can stand and make certain connections for him or herself.

LaCAVA: Interestingly, I’ve had a similar conversation with a nonfiction writer who draws from her own life, about the importance of the white space. It was Kate Zambreno in regards to Book of Mutter, which came out last month, and is a wonderful book. She was adamant at these breaks being present and in certain form.

There is also the preface to Mallarme’s A Roll of the Dice in it: “The ‘white spaces’ in effect, assume importance … The paper intervenes whenever an image, of its own accord, stops or withdraws, accepting the others that follow, and since it is not a question, as always, of regular ones of sound or verse—but rather of prismatic subdivisions of the Idea…”

SHAPIRO: I love that. Rachel Cusk said something recently about suffering and writing fiction, to the effect of, once one has suffered enough, the idea of making up Jane and Jim and have them do things to each other loses its appeal. What I think she’s talking about there is the distilling of experience—call it what you may, fiction or memoir. I would have been perfectly happy to call Hourglass a novel. I’d be perfectly happy to write fiction that is sort of coming directly from experience.

I reject and am offended by the idea that this kind of work is confessional. There’s nothing confessional about crafting and shaping a story out of a lived life. In fact, it’s quite the opposite—the writer has to be able to transcend the life, to see it as if standing outside of it, in order to be able to make something of it. There’s something enormously satisfying and gratifying about crafting something, taking all that chaos and giving it shape.

LaCAVA: There is also that powerful quote by Chris Kraus: “‘I think that ‘privacy’ is to contemporary female are what ‘obscenity’ was to male art and literature of the 1960s. The willingness of someone to use her life as primary material is still deeply disturbing, and even more so if she views her own experience at some remove…” That quote continues and goes into how rattled people may be that a woman can regard the material of her life cooly, with remove. There is also the idea that an audience may think it’s entitled to know you.

SHAPIRO: It’s not even that think they’re entitled to—it’s that they think they do [know you].

LaCAVA: And so for you to even say, “You can’t possibly know me from reading my books,” somehow that implies that you’re not doing what you’re supposed to do?

SHAPIRO: Frank McCourt was a neighbor of ours and we were at a dinner party once in Connecticut and he was sitting across the table from me, seated next to a woman who had never met him before. He was being Frank—lovely and kind, helping with her chair—and she said, “You know this is so strange, I feel like I know everything about you.”

Frank looked at her and said, “Darlin’, it’s just a book.”

LaCAVA: We are having this conversation weeks before Hourglass actually comes out. What is most frightening to you about its release?

SHAPIRO: It’s one thing for me to be okay with understanding that people are going to misread me or make certain assumptions about me—either flattering or not, it doesn’t matter—just deciding who or what I am based on reading my book. It’s quite another thing for them to make certain assumptions about my husband, or about even my marriage.

So, the real tricky high wire act of this whole creative process is that I really wanted to inquire, I wanted to explore, and yet I also wanted to protect. And keep sacred, I guess protect isn’t even the right word.

LaCAVA: Here again is that idea of abstraction on the page. Even though this is a book, it is one that announces that text-written memories—can’t tackle an experience. You make a point of including journal entries and lists in Hourglass, which in a way makes clear that the book itself is altogether different from journals and lists. It’s the abstraction that arises between the lines. And it makes the short work seem almost painterly to me in that way.

SHAPIRO: I love that. In a way that’s a comment on memoir itself, which is that all memoir can do is pin the very elusive moment in time.

LaCAVA: “It can’t even say really exactly what happened.”

SHAPIRO: No it can’t. It’s pinning that self—the self that’s writing it—with the self that self is writing about in time, in that moment. I think it’s why it’s possible to write multiple memoirs, which is not something that I understood earlier in my writing life. After I wrote my first memoir I thought, “That’s it, that’s my memoir.” But as I’ve gone on in my life as a writer, my obsessions—which is to say, themes—have deepened in ways that have made that pinning of the self the most interesting endeavor—telling stories out of lived experience rather than shaped out of imagination.

HOURGLASS IS OUT TOMORROW, APRIL 11, 2017.