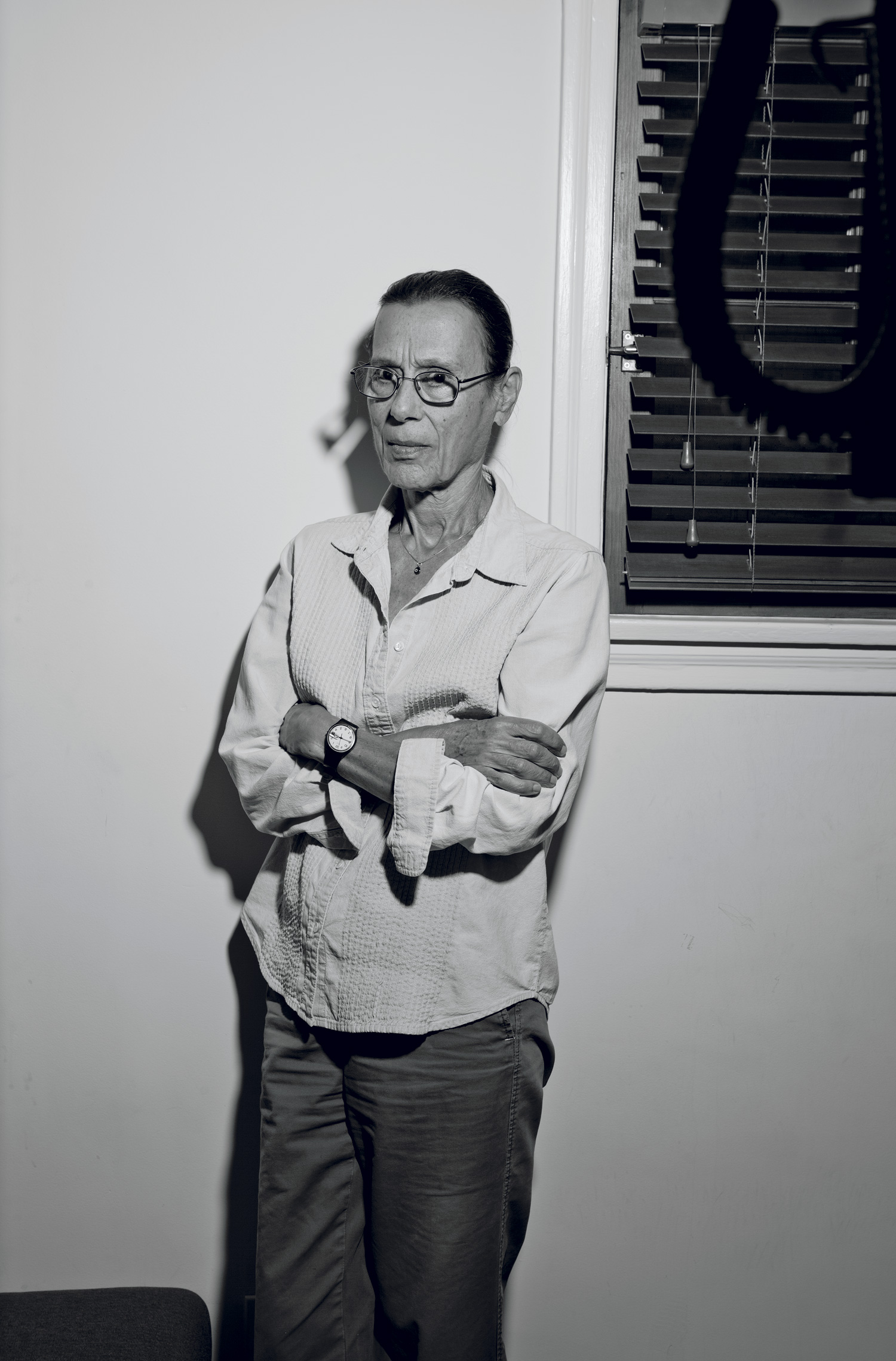

Dance Mom: Yvonne Rainer

WHILE DANCING, I SPOKE ABOUT THE DIFFICULTY OF DOING IT AT MY AGE. I WOULD SAY, ‘THIS IS SUPPOSED TO BE A SLOW RISE OF THE LEG. WHY CAN’T I GET MY LEG UP HIGHER THAN THIS NOW?’ “-yvonne Rainer

In 1962, San Francisco native Yvonne Rainer, then 27, and fellow dancers Ruth Emerson and Steve Paxton approached the Reverend Al Carmines of Judson Memorial Church on New York City’s Washington Square Park to ask if they might use the sanctuary to present dances. The result was the Judson Dance Theater, which changed the course of dance history. The 50th anniversary of the first Judson Concert of Dance has been celebrated throughout 2012 at a number of venues, with many of the original Judson participants revisiting the past or making new works.

Rainer was the most radical among the Judson dancers, and with her essay “A Quasi Survey of Some ‘Minimalist’ Tendencies in the Quantitatively Minimal Dance Activity Midst the Plethora, or an Analysis of Trio A,” she became their theoretician. Published in Gregory Battcock’s groundbreaking anthology, Minimal Art, in 1968, Rainer’s manifesto linked the new tendencies in dance to those in sculpture. The essay’s title is telling of Rainer, who has always been voluble and funny, as well as tough-minded and searching. In 1963, Rainer’s dance Terrain became the first full-evening work at Judson, and her famous Trio A, first performed at Judson in 1966 by Rainer, Paxton, and David Gordon, has lived on in many incarnations and become not only Rainer’s signature dance work but an iconic 1960s dance in a league with George Balanchine’s Jewels, Merce Cunningham’s Walkaround Time, and Alvin Ailey’s Revelations. A continuous, uninflected series of deceptively simple movements in which the dancers never allow their gaze to meet that of the spectator, Trio A takes roughly five minutes to perform. It was originally meant to be teachable to anybody, although Rainer would be the first to say that it’s far from easy to execute. Nevertheless, for the past several years, you could walk into many a museum and see a group of dancers doing it.

In the early 1970s, Rainer founded an improvisatory New York City-based dance group called Grand Union with a number of her Judson colleagues and went on a life-changing trip to India. At the height of protests against the Vietnam War, she and several Judson dancers also performed a notorious version of Trio A nude and draped with American flags. Then she unexpectedly turned to narrative, which led to an entirely new career in filmmaking. From 1972 to 1996, Rainer made seven feature-length films, beginning with the autobiographical Lives of Performers, an investigation of what she called “the nuts and bolts of emotional life” that “shaped the unseen (or should I say unseemly?)” side of minimalism, and ending with MURDER and murder, a searing comedy about breast cancer and lesbian love. But in 1999, something unexpected happened: Mikhail Baryshnikov asked Rainer to choreograph a new dance for his White Oak Dance Project. She returned to her 1960s dances—”raiding her icebox,” as she puts itand made After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, which thrilled audiences at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Since then, Rainer, now 78, has made five more major dance pieces, responding to commissions from Dance Theater Workshop, Performa, Documenta, the Getty Trust, Yale, and she will be performing on January 24, 25, and 26 as part of Danspace Project’s Judson Now series. In her latest dances, she still employs the collage style she developed in the 1960s, a complex blend of found and invented movement, comic send-up and political commentary.

DOUGLAS CRIMP: Let’s start with your recent dance, Assisted Living: Do You Have Any Money? The six dancers recite a variety of lengthy texts, including jokes, newspaper stories, and film monologues, while performing complicated combinations of steps. When I saw the work in rehearsal, I found it difficult to follow the words and movement at the same time, so I can’t imagine how anyone can actually perform them together.

YVONNE RAINER: Well, it’s a whole new challenge for my dancers. I didn’t know whether they could do it, and they were kind of dubious, but it turns out they can do it. My dancers are not trained actors, but there are techniques. I guess from the spectator’s perspective it involves a kind of de-centering, a splitting of focus—like not being able to take in everything on stage in a Cunningham dance when different things are happening at the same time. The dance events in Assisted Living: Do You Have Any Money? all happen as unison duets or trios, so I hope that the doubling and tripling of the movement makes it a bit easier to focus on the speech. I don’t expect you to follow the monologues in their entirety. But you can get the gist, or go back and forth with your attention. Of course, a second viewing makes the process easier. But anyway, the aesthetic of it is very strange. I don’t know quite how to talk about it yet. First of all, the dance is set up in a carnival-esque way, with me being rolled in, sitting in a big, overstuffed chair. I stand up in it and read a text like a car- nival barker trying to con his audience into seeing the freak show: “Step right up, folks . . .” There’s a basic step that I worked out with them, which has its origin in a solo I made in the mid-’60s called At My Body’s House—what we call the petit pas, which is a series of simple dance steps that they do in unison at the very beginning. After that, most of the dancing comes from Laurel and Hardy shorts. There’s also a ballet adagio that Emily Coates and Keith Sabado do that Keith was first using to warm up the dancers, an academic exercise with arabesques and développés. While the two of them are doing the adagio, Keith recites an academic description of Keynesian economics, so there are these two kinds of academic things going on at one time from two different traditions, one from ballet and one from economics.

CRIMP: Keynes was married to a ballerina.

RAINER: Keynes? But I thought he was gay.

CRIMP: He was, and he was also a balletomane. He married Lydia Lopokova, who was one of the stars of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

RAINER: Hmm . . . So that’s one of the first combinations of texts and dances. And so it goes. There’s a quote from Emma Goldman.

CRIMP: And there’s Eric Emerson’s monologue from The Chelsea Girls [1966], which you found in my book on Andy Warhol’s films. Are all of the texts appropriated?

RAINER: Yes. I didn’t write any of the texts.

CRIMP: And the movement, too, is mostly taken from elsewhere.

RAINER: Yes. Except for the petit pas, it’s all taken from elsewhere.

CRIMP: You spoke while dancing your very first dance—Three Satie Spoons, from 1960—saying, for example, “The grass is greener when the sun is yellower.” And you’ve continued to use spoken language in many of your dances. When you did Three Satie Spoons, had you heard anyone else use the spoken word in a dance? What made you think you could get away with it?

RAINER: I certainly was not the first to do it. From what I understand, some of Merce Cunningham’s early solos had speaking in them.

CRIMP: Yes, I was thinking of Cunningham’s How to Pass, Kick, Fall, and Run, in which John Cage recites stories while the company dances. But that was later, in 1965.

RAINER: Yeah. And in that one, the dancers don’t speak. That’s a whole other ballgame. Also, I’m interested in the idea of “radical juxtaposition,” a term coined by Susan Sontag to describe Happenings, putting two things next to each other, or one after the other, that don’t have any obvious connection. I think it can be used to characterize all of my work in both dance and film.

CRIMP: It’s interesting that in your best-known work, Trio A, you don’t use language.

RAINER: Ah, that’s not true! I don’t think you saw me doing it at Judson two years ago—it’s probably the last time I will ever do it because it gets harder and harder for me to do. While dancing, I spoke about the difficulty of doing it at my age—which, it turned out, produced a laugh riot. I would say, “This is supposed to be a slow rise of the leg. Why can’t I get my leg up higher than this now?” And then, “Oh, just do it and get it over with.” There were two performances, and I even talked during the first performance about being in a state of extreme stage fright because I hadn’t performed for a while.

CRIMP: But that isn’t how most people would know Trio A. It’s known as a work that doesn’t have that quality of radical juxtaposition, except, perhaps, for the fact that each of the three dancers does it at his or her own pace, so they go in and out of sync. The first time you did it, at the Judson Church, you had wooden slats thrown down from the balcony onto the dance floor at regular intervals throughout the performance. So I guess that’s a radical juxtaposition of sorts. Another phrase you’ve used more recently to describe your work is “pedagogical vaudeville.”

RAINER: Yeah. In the recent work, I think that applies.

CRIMP: Perhaps one could also think of Trio A as having a certain pedagogical value.

RAINER: Yeah, you might also say that Trio A is a kind of lexicon of movement possibilities.

I’m interested in how things don’t work, putting things together that don’t fit “– Yvonne Rainer

CRIMP: You were just saying that when you recently danced Trio A, people saw it as a laugh riot, but your funny side is very often overlooked. Your work is often seen as overly intellectual.

RAINER: Right, I don’t know why. Perhaps because of my association with minimalism. In the standard view, Judson Dance is seen as part of minimalism. I hope this Danspace series will disabuse people of that notion. You know, my work at Judson was very eclectic, and the participants at Judson came from very diverse backgrounds, training, and disciplines. But the pervasive view of Judson is of me and Steve Paxton walking and running.

CRIMP: “Ordinary movement” became the catchall idea associated with Judson.

RAINER: It’s true that I explored so-called “pedestrian movement,” but it’s always been in relation to other kinds of movement. My work requires trained dancers.

CRIMP: Although there are early pieces, like We Shall Run, that could be done by untrained dancers.

RAINER: Well, that is an example of a more minimal piece. But, even though the only movement in that piece is trotting around, I juxtaposed that movement with a very dramatic section of the Berlioz Requiem. So I was always interested in mixing it up.

CRIMP: I wish people would pay more attention to the vaudevillian aspects of your work. Even the “one thing after another” aspect of minimalism provided you a structure of radical juxtaposition in the late 1960s—pieces you called Performance Demonstrations, Composites, or Fractions, in which unrelated events followed one after another but didn’t necessarily seem to have much to do with one another. They had very much the character of vaudeville, where a ballet pas de deux might be followed by a trained seal act or a juggler. In fact, you did put a juggler on stage with your dancers in The Mind Is a Muscle in 1968. And you’ve also done a lot of things, like, say, Chair/Pillow from Continuous Project—Altered Daily, in 1970, in which a group of dancers performs an on-the-beat routine with folding chairs and pillows to Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep, Mountain High.” It often brings people to their feet.

RAINER: Yeah, Chair/Pillow is a crowd-pleaser.

CRIMP: This goofball entertainer side of you interests me, especially in relation to your lifelong commitment to the avant-garde. How do these things work together for you?

RAINER: I’m interested in how things don’t work, putting things together that don’t fit. You know, vaudeville and pratfalls and slapstick don’t fit with what’s going on in Syria now. Not that I would put those two things in a dance, but my daily life—I’m a news junkie—is so infused with reports of atrocity. It makes me feel helpless and demoralized, what leaders of the world perpetuate— it’s horrific. And I have to get my response to it into my work in some way. Like in the earlier Assisted Living piece—Assisted Living: Good Sports 2. Toward the end, the dancers are lying on the floor with their heads on each other’s bellies, laughing their heads off, and I go toward them holding a microphone and say, “Have you heard the one about Steve Jobs and the Chinese iPhone factory worker who had half his face blown off? They go into a bar, see, and . . .” I riff on this impossible situation. I had just been reading in the paper about the conditions in the iPhone factories in China. And we’re all complicit and helpless in these technological advances and hysterical marketing of devices that we must have in order to go on with our lives. They have us by the short hairs. My audiences are all primed in the same way—they read the papers, too. I know I’m delivering these missals to the already persuaded. But it’s an attempt to keep up a kind of recognition and . . . Not guilt, but awareness and mutual support, you know?

CRIMP: I’m thinking back to an earlier moment when you responded to a political issue in your work, when you did Trio A With Flags for the People’s Flag Show at Judson.

RAINER: Yes, the People’s Flag Show was organized to protest the prosecution of Stephen Radich, a gallerist who had shown a sculpture that allegedly desecrated the flag. It was a huge show in the sanctuary of Judson Church. Jasper Johns had something in it, Kate Millett—anyone who did anything involving the flag was invited to contribute. So five of us who knew Trio A took off our clothes and tied five-foot flags around our necks and draped them in front of us, and we performed Trio A that way. The flags waved around and revealed our privates. I considered it a double protest against censorship and war.

CRIMP: The flag show coincided more or less with the time that you turned from making dances to making feature films. Your first feature film, Lives of Performers, was released in 1972. Was it the political climate of that moment that contributed that change?

RAINER: It was the second wave of feminism. I read Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone. I guess these writings gave me permission to investigate, in that first film, emotional life and sexual ambivalence. It wasn’t so much global politics—that came later. It wasn’t until my third film, Kristina Talking Pictures, 1976, which was about oil tankers and pollution, that I began to explore issues beyond private life.

CRIMP: Or issues that were both personal and public for you—race, breast cancer. When you became a filmmaker, your work became extremely topical. Of course, formally, your films still used the radical juxtapositions that you’d been using in your dances.

RAINER: Right. Initially, I saw an opening between avant-garde film and Hollywood “women’s weepies.” I had followed the “New American Cinema”—Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Andy Warhol—and I saw an opening for using experimental devices in relation to a different kind of content. I didn’t feel I could do that in dance. It was mainly language that would deliver this content. Film offered the possibility of using language in many different forms—voice-over, subtitles, inter-titles, even newsprint pasted on my face, and eventually lip-sync.

CRIMP: I know that filmmaking was more than a fulltime occupation, but during the time you made films, did you continue to have an interest in dance?

RAINER: I continued to follow the work of my peers. I went to every Trisha Brown or David Gordon concert. But otherwise, I pretty much lost contact with dance. I still had images of movement, and I would pass them along to Trisha, knowing she wouldn’t use them. [laughs]

CRIMP: Then in 1999, you danced a version of Trio A called Trio A Pressured at Judson, and Mikhail Baryshnikov saw you and invited you to make something for his White Oak Dance Project.

RAINER: Right. I raided my icebox to make After Many a Summer Dies the Swan for White Oak. Fortunately, Pat Catterson offered her services. Pat had studied with me at Connecticut College in 1969, and she’s still going strong and remains devoted to my work while doing her own choreography. She knew Trio A and remembered other things from my past. She has a memory like a steel trap. And so I was able to make a kind of mélange using fragments from my 1960s work, together with some new speech fragments. There were six dancers, including Baryshnikov, and they passed around a microphone and recited deathbed utterances that I culled from various sources, some remarks about aging, some political stuff.

CRIMP: I guess at the time you figured After Many a Summer Dies the Swan would be a one-off thing rather than what it led to: a full-scale return to choreography.

RAINER: Swan was followed by Past Forward, White Oak’s Judson program. Misha continued to be interested in this period of work, and I taught Trio A to his company. In the meantime, I made a video using rehearsal footage from Swan—After Many a Summer Dies the Swan: Hybrid and Rainer Variations with Charlie Atlas. Then came the commission from Annie-B. Parson for the Sourcing Stravinsky program at Dance Theater Workshop.

CRIMP: You did, in quick succession, two Stravinsky pieces, AG Indexical, with a little help from H.M., and RoS Indexical. So you raided other choreographers’ histories, remaking—or revisioning, to use your term—Balanchine’s Agon and Nijinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

RAINER: I was interested in those ruptures in dance history. The Rite of Spring is the most notorious, of course, then, in its own way, Agon is another, and it’s one of my favorite Balanchine pieces. So, yeah, I took those on, again with Pat Catterson’s help. Now I’m doing another revision, strangely enough. I teach at the University of California, Irvine, and I have eight performers, a few of them from the dance department and the rest from Studio Art—I’m making something called RoS Indexical Indexical. [laughs] I’m culling from RoS Indexical, much of which was itself culled from Millicent Hodson’s reconstruction of The Rite of Spring, but also again raiding that early icebox to disinter some movement games for the nondancers. It may turn out to be an interesting mess. I’ll use the same soundtrack from the BBC Riot at the Rite, but none of the movements will be on the music. I’m doing it in reverse, beginning the dance by copying the end moves of RoS.

CRIMP: You certainly ask a lot of your dancers. But, then, you ask a lot of yourself. I hope that I get a chance to see it.

RAINER: Not many people are gonna see it. [laughs]

CRIMP: You never know. You may end up touring it.

RAINER: Ha! In a blue moon.

Douglas Crimp is a Fanny Knapp Allen professor of art history at the University of Rochester.