politics

Congresswoman Cori Bush Tells Janelle Monáe How She Plans to Change the World

Over the course of Cori Bush’s first ten days in Congress, she withstood a siege against the U.S. Capitol by right-wing extremists, filed a resolution to expel her Republican colleagues who objected to the election results, and called President Trump the “white supremacist-in-chief” during her first speech on the House floor. Then, she voted to impeach him. For most of the country, it was a breathless introduction to the first Black woman to represent the state of Missouri in Congress. But for those who already knew Bush from her days as an activist and organizer in St. Louis, it was business as usual.

In 2014, Bush was an ordained pastor and a registered nurse struggling to provide for her two children when an unarmed, 18-year-old Black man named Michael Brown was gunned down by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Galvanized by the uprising that followed, Bush helped set up a crisis-response tent to provide care for protesters as they clashed with law enforcement. What she saw during that period—officers in SWAT gear using tear gas and rubber bullets against citizens without weapons—would change the course of her life. In 2016, Bush ran for the U.S. Senate, but placed a distant second in the Democratic primary. Undeterred, two years later she took on the longtime incumbent William Lacy Clay in the race to represent the first congressional district of Missouri. Her progressive campaign, in which she called for a $15 minimum wage, free state college tuition, and Medicare for All, was chronicled in the Netflix documentary Knock Down the House, which ended with a tearful Bush conceding defeat. That brings us to 2020, a year when the 44-year-old mother-of-two’s Black Lives Matter message and advocacy for universal health care took on newfound urgency. This time, buoyed by a national profile, a grassroots campaign, and an endorsement from Bernie Sanders, she beat Lacy Clay in the biggest upset victory since her friend Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did it two years prior. Now, as she tells her fellow Midwesterner Janelle Monáe, the real work has just begun. —BEN BARNA

———

JANELLE MONÁE: I have watched you blossom since the Ferguson movement, and I can’t say it loud enough as a fellow Midwesterner: I take such great pride in seeing you become the first Black congresswoman of Missouri. That is huge.

CORI BUSH: Oh my gosh, thank you. To hear that you knew about me years ago, that blows me away, because you are absolutely phenomenal. You wear so many hats in amazing ways.

MONÁE: And speaking of hats, you are a registered nurse.

BUSH: Yes.

MONÁE: You are an ordained pastor.

BUSH: Yes.

MONÁE: You are a mother of two.

BUSH: Yes.

MONÁE: And you are also at the forefront of the Black Lives Matter movement. What has kept the fire lit under you?

BUSH: It’s remembering every bit of pain. I’m still at a place where I remember what it was like to sleep in a car with two babies. I remember when no amount of blankets could warm us up. I remember how it felt when I was lying on the concrete and police officers were stomping on me with their steel-toed boots. I remember thinking, “Who do I call out to for help when it’s the police who are hurting me?” I remember going through a very violent sexual assault right after my very first race. I didn’t get justice and almost lost everything because the system is not set up to help victims of sexual violence. It’s knowing that if I push hard enough, I can prevent someone from going through what I’ve gone through. That’s the fire.

MONÁE: The fact that you have gone through all of that is a testament to what you can do. You should not have had to go through any of those traumatic events, and I wish I was with you now because I would wrap my arms around you, but I want you to feel me wirelessly hugging you.

BUSH: I do.

MONÁE: I want to talk about what it was like after you lost your first race, because I watched Knock Down the House and was crushed when you didn’t win. I saw you rocking back and forth and crying when they gave you the results. I was crying, too. What gave you the confidence to run against William Lacy Clay again, and what did you do differently the second time around?

BUSH: The first time felt like a mission, like I was called to do it, even though, honestly, I didn’t want to.I didn’t feel like I had what it took, because I’d never been in politics, but I felt in my heart that it was what I needed to do. And so I pushed forward. When I didn’t win, it was like, “Okay, did you complete the mission? If it was a mission then, isn’t it still a mission?” The night that we lost, I couldn’t find my team. Tears were in my eyes, and I was like, “Where are my people?” It turns out that they were huddling in a corner, organizing the next race. I was thinking to myself, “I don’t want to run again.” And they were like, “You get yourself together and we’ll take it from here.” With the second campaign, Knock Down the House helped me gain visibility, which helped with fundraising. And then Bernie Sanders asked me to be one of his national surrogates for his presidential race, so I was traveling the country, not only with Netflix, but for him. And then I thought about what people said they would change about our current congressperson, and I made sure that I was doing the opposite. Then when COVID-19 hit, people were like, “Cori, for years you’ve been about Medicare for All. Now we get it.” And then when I ended up sick with COVID-19 for two months, I was public about it. I went on social media and showed videos of what was going on. People saw that I wasn’t backing down. And three days after I felt better, George Floyd was murdered, so I hit the streets to protest. People then understood, “She was protesting years ago, and now she’s protesting even while she’s running for Congress. It must mean that this is who she is.”

MONÁE: Your spirit will not be suppressed. Even when our bodies give out, even when we’re physically in pain, we’re still pressing on because that is what we are here to do. We are on assignment. Both of my parents were working class. My dad was in and out of prison. My grandmother was a sharecropper from Aberdeen, Mississippi, and migrated to Kansas City because one of her siblings was going to be lynched for having been with a white woman. The people raising me were on and off drugs, and are recovering addicts. Nothing was designed for me to be where I am today, and I look at my life, and I look at your life— we beat the system.

BUSH: We sure did.

MONÁE: When you first arrived for your congressional orientation, you were wearing a mask that said “Breonna Taylor,” and there were Republican members of Congress calling you Breonna, because they thought that was your name. These people were so out of touch that they had no idea who she was. What was that like for you?

BUSH: When the first person came up to me and called me Breonna, I was just looking around like, “Are they talking to me? Is this real?” Then I had to discern the spirit behind it. “Are they being nasty, or do they just not know who she is?” When the last person came up to me and said, “Hi, you must be Breonna Taylor,” I was really upset. I said, “I don’t understand how we’ve gone through months of protests all around the country, and you mean to tell me you have never heard her name before?” When I realized they just had no clue, I told each of them exactly who she was. “She was an award-winning EMT. That’s who this woman was.”

MONÁE: Wow. What are some of the most urgent issues you’re facing?

BUSH: We have to fight for a robust COVID-19 package. In my district, Black women have carried the most cases and Black men are the ones who have suffered the most deaths. We need survival checks, a direct recurring cash payment of $2,000. We need resources for our schools so our children are taken care of, and stabilized housing, canceled rent and mortgages, and eliminated student debt. Those are some things we need to do right now. And a $15 federal minimum wage, to start. We also have the other pandemic of police brutality, so we need to tackle this criminal legal system head-on. I’m a “defund the police” person, because I believe we overfund our police departments and underfund our social services. We can do better as a society, because you can’t just keep killing us and think you’ll get promotions.

MONÁE: I want to talk to you about St. Louis. Tell me about the people in your community, and what you want people to know about the district you represent?

BUSH: St. Louis is my heart. Until I started traveling a lot, I didn’t realize I was so used to being in a space where there are so many people who look like me. It wasn’t until I started going to other places where it was like, “Okay, where are the Black people?” But there is such amazing talent in St. Louis—the music, the filmmakers, and the food. St. Louis food is crazy! But we also have high crime, high poverty, and environmental racism. Our Black children are ten times as likely to go to the ER for asthma than white children. Black infant mortality is six to one compared to a white baby, and Black maternal mortality is four to one compared to a white woman. People are hurting. I go to sleep and I hear gunshots throughout the night. And our people, we don’t have to live this way. We are so accustomed to struggle and violence that we don’t know another way. We don’t even realize we live with PTSD. But it’s a new day, because now the people of St. Louis have a congresswoman who loves each and every one of them.

MONÁE: And I believe that. As a progressive Democrat, how do you see your role in the Democratic Party, particularly in relationship to this new administration?

BUSH: I’m walking in the door with a lived experience others may not have. I call myself a “politivist,” because I’m a politician, but I’m also sitting in this seat as an activist. When I think back to when I was a low-wage worker, I couldn’t afford to pay my bills, my credit was getting bad, and I didn’t have health insurance. I had to go to the hospital for a toothache. I know what it’s like to live without health insurance, and to bury my patients because they were rationing their insulin. My role is to serve the people of my district, no matter what. They’ve been under leadership that wanted incremental change for such a long time, but change can’t wait. It’s our responsibility as progressives to do what we can to push the Biden-Harris administration, and the Democratic establishment, to be bold. I’m going to fight to make sure every single person has access to health care, housing, and education. We’re talking about whether or not somebody can live. This is about life or death. As an organizer, I know I have the ability to bring people together to accomplish things nobody expected.

MONÁE: Have you met Congresswoman Maxine Waters?

BUSH: Yes, I have. She’s wonderful.

MONÁE: She’s like a grandmother to me and her grandson works on my team. Hearing you talk, I immediately thought about her, and about the other women in Congress who have embraced you. I saw a photo of you with The Squad, and it’s great that you can come in and have some sisterhood. Can you talk about how you see yourself in relation to those four women [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib], and how you plan on working with them?

BUSH: I’m so proud to be a part of The Squad, because they represent regular people and organizers and activists who have been doing the work on the ground in our communities. We’re bringing the flavor of our communities to Congress. We understand that progressive power is the people’s power. To see this movement being led by people who live paycheck to paycheck, people who have been victims of police violence, people who don’t get the care they were supposed to have through health insurance—we’re bringing those voices to the forefront.

MONÁE: Y’all are, quite frankly, shaking shit up. I’m not interested in things going back to how they were before Trump was in office. We’ve got to have a whole new vision. We’re going to have to do something more radical and more fresh, and I see it happening because you and these other women answered the call. Can you talk about the day-to-day changes in your life that come with becoming a first-time congresswoman?

BUSH: It was a huge transition. I didn’t think enough about what it would look like to win, and what it would cost. I assumed there would be some kind of income for me to sustain myself and my family, but that wasn’t the case. The system is not set up for people who aren’t millionaires. I had to quit my job to be able to run in 2020, so financially it was a strain. All of a sudden, you’ve got to have outfits for orientation, you’ve got to have business clothes, and it was like, “Where do I get all of these clothes from? Who pays for the shoes? The jewelry?” It was a huge thing. So I just put it out there that I was going to a thrift store to buy my clothes, and other people reached out saying, “I’m so glad you spoke up about that, because that’s what I’m going to need to do, too.”

MONÁE: When I started my career, I was living in a boarding house with five other girls, going to community college and using my college refund to pay for my CDs to get pressed. Whenever I needed to perform or make an appearance, I couldn’t afford a stylist, so that’s part of the reason why I developed a uniform, those black-and-white outfits you’ve seen me in. I’d go to a thrift store and find black pants, go get some nice white button- down shirts from Gap or Banana Republic, and get a suit jacket. It freed me up to not have to worry about what I looked like. It was my superhero uniform. You don’t have to have a new look every time they see you. Find your one look, girl, and get to work.

BUSH: I love that. Oh my god.

MONÁE: It’s a lot of pressure to be a woman, and to be a Black woman, and to have curves, and to have a different look than everybody else.

BUSH: Yeah, it is a lot of pressure. That story just messed me up. [Laughs]

MONÁE: It’s true! Let’s talk about learning the day-to-day work of being a congresswoman. What is the process? What are you doing?

BUSH: The congressional orientation was really helpful in showing us some of the resources that can help us along the way and, more generally, what the day-to-day job is. And then it became about hiring good staff. We hired a phenomenal team who have worked for other Congress members in the past, and they are walking me through it step by step. I’m learning where to be, what kind of calls I need to take, and what the votes mean. We also have people from my district who I brought with me. And then I have Alex [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez], who always talks to me about making sure I’m personally okay with how I’m voting, or understanding the ins and outs of, like, “Okay, this is how decisions get made, this is what’s going to happen, and this is how I get through it.”

MONÁE: In terms of Black Lives Matter, I know you’re still involved. How do you plan on taking the ideals and the missions of BLM to Washington and using them to incite actionable change?

BUSH: A big part of my network is people from that movement. Being able to bring them and their ideas to Congress is part of it. One problem we’ve had in our movement is when politicians don’t do their homework to find out who they should be talking to in order to get real information about what needs to be done with legislation as it relates to policing. Instead of going to people who are doing the actual grassroots work in different communities, they’ll go to names they’ve heard. Well, those people aren’t the ones on the ground getting their butts kicked every day. They may have institutional knowledge, but you can’t push aside the people who are actually the most effective. The people who are doing the actual deep work. I’m bringing in the people nobody knows about, the people who’ve been out there on the streets of Ferguson and were chased by dogs, the people who were protesting before protesting was popular. I ran for Congress and won with a mandate to dramatically transform our criminal legal system. That has to happen. So I’m coming to Congress to end the structural institution of violence on Black and brown communities. I’m taking that mission from the Ferguson front lines to the House floor. The police violence, the immigration violence, the death penalty, mass incarceration and poverty—I’m coming for all of it.

MONÁE: I’m walking with you. One thing I want to highlight is that I’m queer, but I grew up going to churches that always made me think that if I were anything other than heterosexual, I was going to hell. And when you grow up like that, it psychologically affects you. There are a lot of young, Black members of the LGBTQIA+ family who have felt like that. One of the things I respect and appreciate about you is that even though you are an ordained pastor, and even though I’m sure you’ve had to deal with pastors in the community who are not supportive of the LGBTQIA+ communities, you are our supporter.

BUSH: Yes.

MONÁE: And you want to pass a comprehensive anti-discrimination policy. You want to continue to protect the privacy of transgender Americans. You want to provide mandatory training to public officials and employees to ensure that they better understand the LGBTQIA+ community. You want to develop and implement LGBTQIA+-inclusive public education, which is paramount. You want to guarantee training of gender-affirming health care. You want to ban conversion therapy, end the gay-panic and transgender-panic murder excuse, and ban intersex mutilation. I appreciate you stepping up to the plate and saying, “I’m going to do everything I can to make sure the community is supported.”

BUSH: Those who aren’t oppressed a certain way should help those who are. In Ferguson, white people stood between us and the police, grabbing their batons so they couldn’t hit us. I saw how advocacy for another community can break down barriers. Everybody should know they’re loved. Whenever preachers have said bad things about me because of my stance, I think about how many people’s lives could have been healed and changed, but weren’t because they were looking at one particular thing and not seeing a person. I won’t be that. You don’t have to like me and you don’t have to agree with me, but my job on this earth is to love humanity, so I’m doing that. Love begets more love, so when you love others, other people see that and feel that, and they’re able to go and share that. That’s how we change the world.

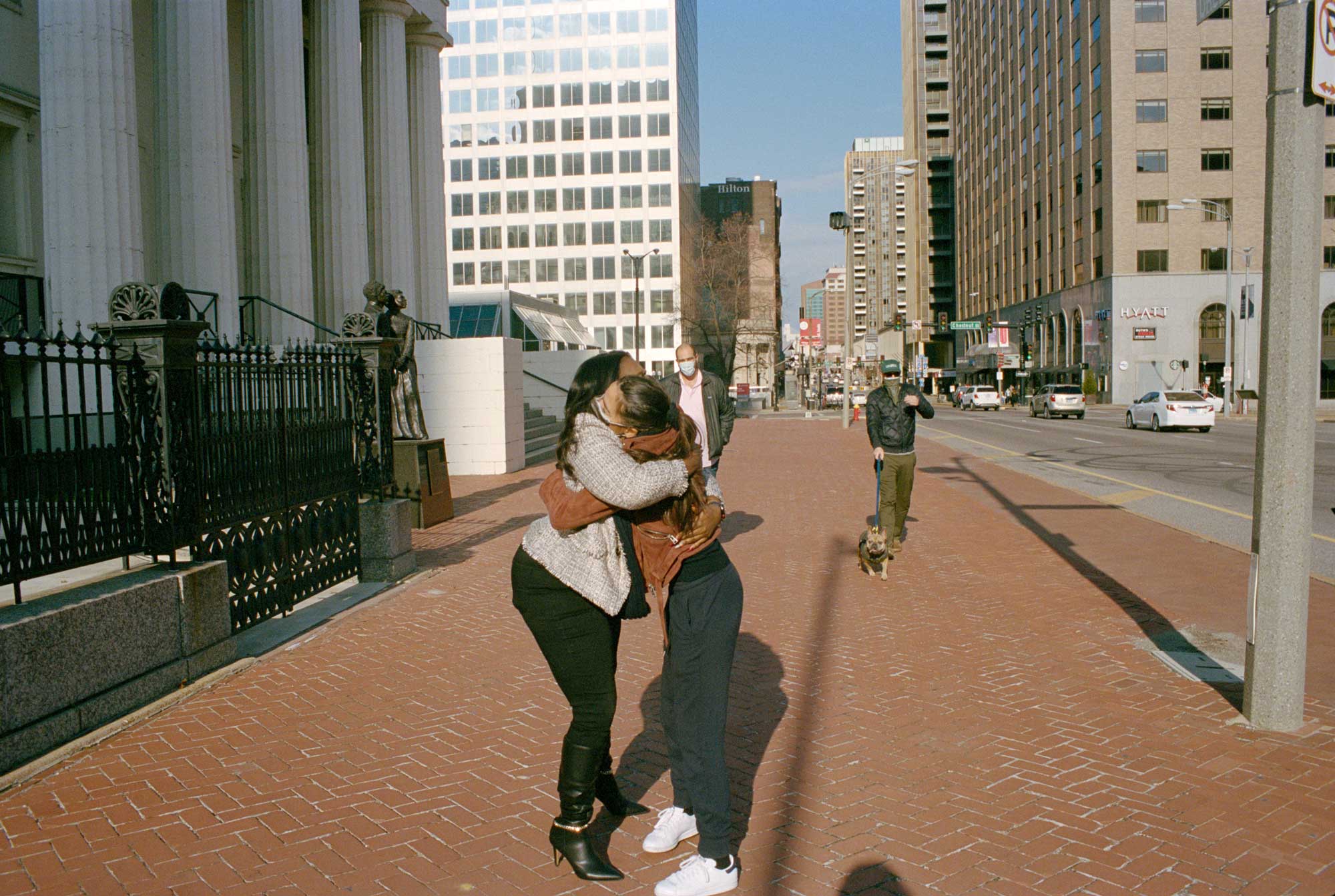

- A surprise visit from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who passed by the Old Courthouse in St. Louis on her morning run.

This article appears in the March 2021 issue of Interview Magazine. Subscribe here.