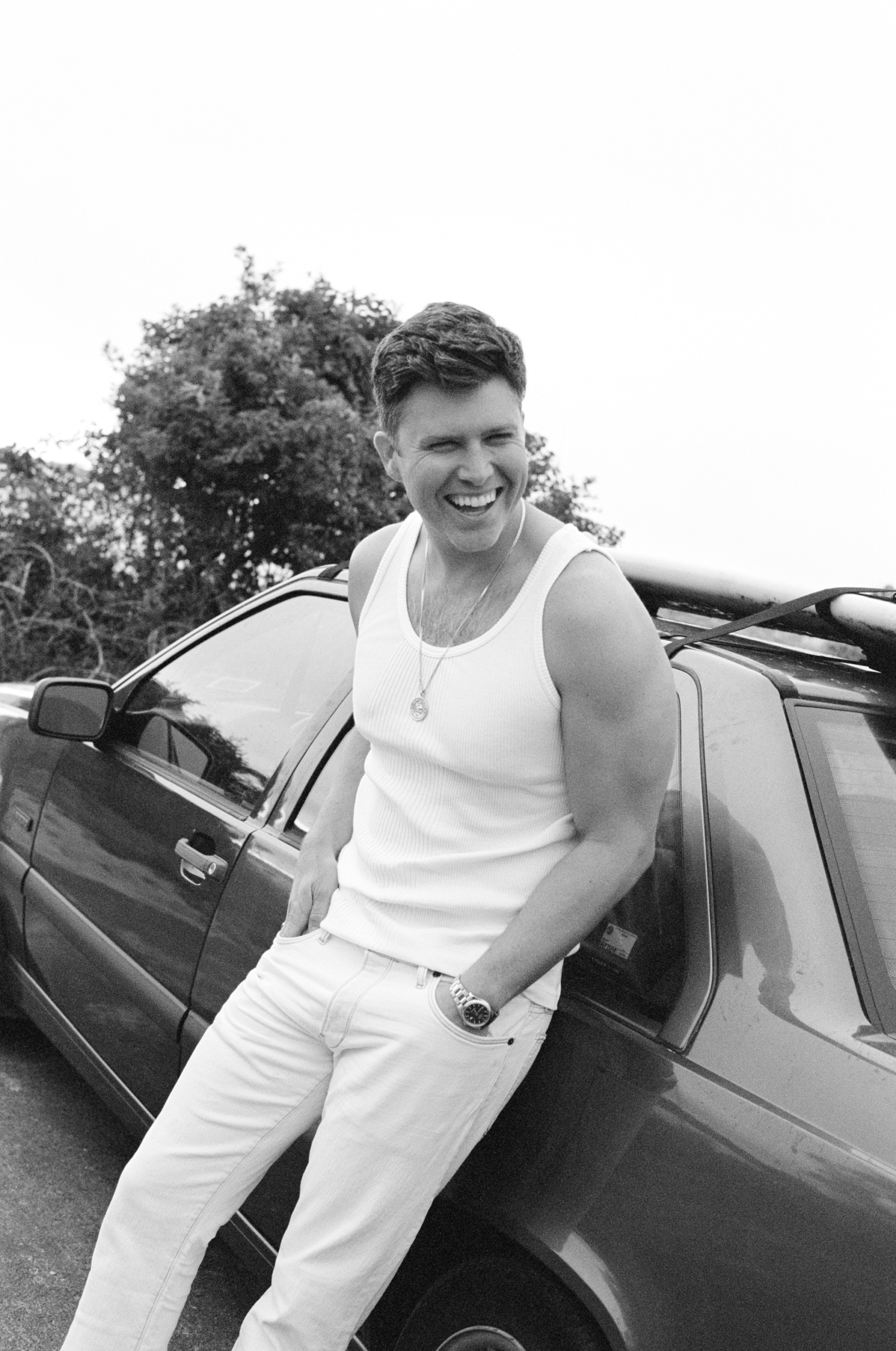

Colin Jost Tells Natalie Portman About His New Book and SNL’s Uncertain Future

Colin Jost is used to writing on deadline. But not just any deadline. As the head writer on Saturday Night Live—a title he shares with his Weekend Update co-anchor Michael Che—Jost spends each week barreling toward 11:30 p.m. on Saturday night, where his week’s efforts will be performed in front of a live audience, whether they’re ready or not. That’s why, with his new memoir A Very Punchable Face, the 38-year-old writer was able to luxuriate in the process of putting words to page as he looked back on his Irish Catholic upbringing on Staten Island, his time as a writer at The Harvard Lampoon, and his ascension at SNL, from fresh-and-punchable-faced writer in 2005, to one of the show’s most influential and enduring voices. And while Jost has lived a charmed existence, those expecting a fairy-tale retelling of his romance with his fiancée Scarlett Johansson should instead brace themselves for cringeworthy tales of crapping his pants and getting tomatoes thrown at him by Parisian teens—in front of Scarlett Johansson. From his temporary home in Montauk, where he’s been waiting out the coronavirus pandemic, Jost connected with his friend Natalie Portman to talk about why it was the right time to write about his past and what the future holds for him at Saturday Night Live.—BEN BARNA

———

NATALIE PORTMAN: Where are you in the world?

COLIN JOST: We’re just outside of the city for a couple days trying to get some stuff in order. We’ve been out in Montauk, holed up there. How about you?

PORTMAN: We’re in California. Just trying to stay solo, which is hard on kids. It’s a weird new world, huh?

JOST: For kids, on a social level, to lose those interactions for a long period is weird.

PORTMAN: It’s really crazy. There’s a lot of stuff that’s coming out that says that they should just open all the kids’ stuff back up, because it doesn’t seem very dangerous for kids and it’s really intense to be taken away from all that social interaction. But anyway, we’re here to talk about the book.

JOST: Not to solve the health crisis?

PORTMAN: Not going to solve the pandemic here on the phone! So why did you even decide to write the book?

JOST: For some reason, it felt like the right moment to start looking back on somewhere between a quarter and quarter-and-a-half of my life. I wanted to write about some of these moments, especially stuff at SNL, while it was still fresh in my mind and while I was still going through it. I wanted to not lose all the details and the sense of how fun some of it was, and how hard some of it was.

PORTMAN: Did you keep journals, or are you just recollecting?

JOST: I’ve kept journals through the years, but I didn’t rely on them. Writing it down at the time helped me remember it, and those were like footholds in climbing toward a book. Do you ever keep a journal?

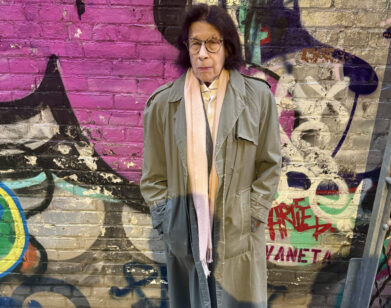

PORTMAN: Not that much, but I’m always really impressed when I read a book and it’s very detailed because I don’t have a great memory. When I read Patti Smith’s book, and she’s like, “Then we ate a grilled cheese sandwich,” I’m like, “Please tell me that you wrote a journal about that.”

JOST: Certain things are probably textured memories, too. I don’t remember almost anything I’ve eaten in the past two weeks. But if she has a really amazing grilled cheese in this incredibly romantic moment, I guess that grilled cheese stands out.

PORTMAN: How did you figure out the title?

JOST: I had written that down at some point as a phrase that I thought was funny because a friend had told me that I have a very punchable face. Several friends have told me that. Then my editor heard it, and she was like, “I think that might be good. Give me a day and let me think about it.” She called me back and she’s like, “I’ve talked to everyone, they love it. This is the title.” It helped shape the book thematically, because then we started talking about how many chapters involved physical or emotional humiliation, and it felt like a good theme running throughout the book already.

PORTMAN: You write about how you’re reserved and it takes a lot for you to open up. How do you decide to tell a strange audience about really private, potentially humiliating things?

JOST: Writing it down makes it so much less difficult to tell strangers. There are a lot of stories that I would feel very comfortable telling my close friends, but that I wouldn’t feel comfortable telling strangers. Somehow writing it down is enough of a distance from the audience. I hope to never be next to someone while they’re reading it.

PORTMAN: When did you write it?

JOST: I did a lot of it pretty intensely in the summers when we had some time off from SNL. I carved out a couple of months where I was writing every day and trying to give myself a deadline.

PORTMAN: Was writing a book really different from writing comedy sketches or stand-up?

JOST: Yes. I found it to be the most freeing process because you’re doing the whole thing before you have much feedback. I think it’s the purest version of my voice, because even with stand-up, you’re responding to an audience and you’re rewriting jokes based on whether they work or not.

PORTMAN: But then when you do get feedback after all that time, does it feel the same as when you’re with a live audience?

JOST: It feels deeper, because you’ve taken longer to do it. I don’t know if you’ve had that experience. If you spent a long time on something or it feels very personal, then any feedback you get is going to feel either harsher or take a little more time to process.

PORTMAN: Was it really different pace-wise? SNL is obviously so fast.

JOST: It was one of the first things I got to write that didn’t have an exact deadline. Every week, as you know from hosting, you’re intensely working toward Saturday, and everything has to be done whether you’re ready or not. That’s its own thrilling thing and such an adrenaline rush. When you don’t have a deadline, you have a little more freedom in terms of being able to go back and look at things again and keep improving them. That feels like such a luxury.

PORTMAN: What are the benefits of pressure?

JOST: You get it done. I don’t know how you are with goals, but when I have to do something, sometimes it’s nice to be boxed in and have to figure out how to get out of the box. That’s a great creative challenge, and sometimes it brings out the best in me.

PORTMAN: Are you a procrastinator?

JOST: I’m a huge procrastinator.

PORTMAN: What’s your go-to?

JOST: It varies. Recently, it’s been online backgammon. I never played until this. I think I’m an enterprising procrastinator. I find new ways to procrastinate just when I think I’ve gotten past the other one. What is yours?

PORTMAN: I’m an online Scrabbler.

JOST: We both picked debilitating vices.

PORTMAN: Exactly. Really cool faults. Have you shared this with anyone close to you yet?

JOST: My backgammon addiction?

PORTMAN: [Laughs] No. Has your family read your memoir?

Colin: They just did.

PORTMAN: What was that like?

JOST: It was cool. My parents said they were so happy they didn’t know that all of this stuff was going on until they read the book. They can’t believe how many times they would have been so deeply worried about my life and my standing in society. They also said that they learned so much about me, that emotionally I talked about so many things that I never would have talked to them about.

PORTMAN: Your chapter about your mom—I have to admit I was fully crying at the end. I think maybe having a son made me feel like, “If my son ever wrote anything like that about me…” It’s so beautiful and she seems like such an incredible person. Did she have conversations with you about women’s equality, or was it just something that you lived with?

JOST: It really is something I just saw through her. As a young man, you’re seeing it in action, so you never question it. My mom was the breadwinner of our family for a long time. She often joked about how many times she’d be in high-level meetings in the New York government, and after she suggested something, they’d say, “Oh, that’s a pretty good idea for a woman.”

PORTMAN: Oh my god.

JOST: Later in the meeting, if someone else suggested something, she’d be like, “Oh, that’s actually a really good idea for a man.” Even when she became a doctor, there were fewer women going into medicine at that time. She was the first medical officer in the Fire Department and the first chief medical officer, so she saw the department change and also the need to keep changing.

PORTMAN: I feel like there could be a whole book about her.

JOST: I know. I wish she would write one. That’s the other thing about her, she’s a very heroic woman and a very hardworking, dedicated civil servant, but she is extremely humble. She would probably never do it, which is why I did it.

PORTMAN: How do you think her influence has affected how you are in the workplace? Even the title of your book acknowledges the privilege of being a straight white male in the comedy world.

JOST: When I started at SNL, Tina Fey was the head writer. She hired me. Amy Poehler and Maya Rudolph were the spiritual leaders among the cast, too. That felt very familiar to me, I think because of my mom, and knowing that my mom had been in a leadership position. I always just equated talent and skill with who should be in these positions. I think now it affects me because such a big thing is having some degree of self-awareness, and that’s not a one-time thing. You have to keep reexamining yourself and your own biases because everyone has them. When Lorne [Michaels] asked [Michael] Che and I to be head writers, we didn’t want to do it unless they were going to promote women to be writing supervisors. That was important to us because we didn’t want it to just be like some guys are getting promoted and there doesn’t feel like there’s any other upward mobility. Of the writing supervisors now, I’m very confident that some of them will lead the show in the coming years. There are a lot of small moments like that which make a big difference over time, and you have to always be looking for them.

PORTMAN: I didn’t realize the stuff you wrote about the Harvard Lampoon, that they take blind submissions, which is so cool.

JOST: I think that’s a big reason why the writing staff at the Lampoon now is at least 50 percent female, maybe more. When you try to eliminate biases that you might not even know you have, you end up with a better staff and a better product.

PORTMAN: And it ends up reflecting the world more, because there are great people from every group.

JOST: During the financial crisis, the one bank in Iceland that didn’t go under was a female-run bank.

PORTMAN: Oh, wow. Do you still read a lot of economics books?

JOST: I read some. I was rereading that Nassim Taleb book, The Black Swan, which is not the one that you did.

PORTMAN: So many people when we were starting that movie were like, “You’re doing an adaptation of an economics book?”

JOST: I’m still fascinated by economics but I don’t pretend to know much about them.

PORTMAN: What do you love to read?

JOST: When the pandemic first started, I got pretty dark. I read [Joseph Conrad’s] Heart of Darkness again. I read [Evelyn Waugh’s] A Handful of Dust. I got back into some Cormac McCarthy. I also like reading things like David Sedaris that feel like candy after reading Heart of Darkness. What about you?

PORTMAN: I read a lot of essays. I read a lot of Rebecca Solnit. I read a lot of science stuff recently. I’ve been trying to dip into race teachings, and also revisiting Audre Lorde and James Baldwin. It’s been nice to at least have time to dig in and think about things.

JOST: Do you end up reading a lot of fiction that might translate to film in some way?

PORTMAN: I do, but I’m always wary of it because I feel like I don’t have that much time to read, so when I do read, I want it to be what I want to read. If it’s not good in the first 150 pages, I’ll stop even though that’s really hard for me because I like completing things. Are you looking at things to write or adapt?

JOST: When I read something I love, I often think, “Oh, my god, I would love to live in this world more,” but there aren’t that many that I can actually see cinematically working. So many books that we love, the way the author writes them is 75% of the magic.

PORTMAN: Why do you feel like you need to leave SNL? It feels like you’re saying you’re going to leave at the end of the book.

JOST: Honestly, part of it is talking myself into it. You’ve experienced it very fully as a host and also being backstage and hanging around. It’s a really addictive place to be, and the people there are so on it and sharp and dedicated. I have such a fear of leaving that world because I just sense that that’s a rare thing. How do you find moving from job to job?

PORTMAN: You keep trying to turn this into an interview about me!

JOST: I get uncomfortable talking about myself.

PORTMAN: It’s a very nice quality. The experience at SNL is so much fun. I can only imagine how hard it would be to leave, but also that it’s a really intense rhythm to sustain. How was it doing the remote shows?

JOST: It was very strange. It was great to have something to focus on during the COVID times, because there’s so much anxiety in general. And it was so nice to see everyone even though you were seeing them on Zoom. Being around people in comedy when there’s a crisis like that happening is such a reassuring thing because, immediately, Kate is on Zoom joking about something and it makes you feel like things are okay.

PORTMAN: Is there a plan for coming back, or is it up in the air?

JOST: It’s very up in the air because we don’t know what the legal setup would be. I think most of our cast members and writers would show up, even if there was a 100-percent chance of getting COVID. I think most of us are desperate for that creative outlet, especially with the election coming up. If there’s any way to be back, we will be, but we’re waiting to see what’s feasible and what level of risk we can tolerate or NBC will allow us to tolerate.

PORTMAN: I found myself almost surprised at you being so open about your political views because I associate you with the news somehow. Do you feel like you’re supposed to have any semblance of being objective even though it’s obviously comedy?

JOST: It’s weird. I honestly do feel like sometimes I have to hold myself to the standards of a regular news anchor, which is dumb. I don’t know why I have that. When I got Weekend Update, I told my grandma that I was going to do Weekend Update, and she was like, “Oh, that’s great, because someday that could turn into a job as a real newscaster.”

PORTMAN: I love that.

JOST: It’s a very hard thing to balance. I want to be open-minded and hear people out and understand where people are coming from. Having empathy for people whose viewpoints are different from yours is so important because even if you’re still disagreeing with them, you’re trying to understand how they got there. Even if that person is a lost cause, it sometimes helps you when you’re dealing with someone who isn’t a lost cause. You’re understanding what the past is, what takes people to the dark side. I stumbled into a great Star Wars reference there. That somehow was not planned. [Laughter.] You want to know what things happen in people’s lives that make them close off their minds or close off their hearts to positive action. It’s really weird being a newsperson, and there’s some sense that you want to feel like you can hit both sides. Right now it’s so skewed. There’s no oxygen for the other side right now. Think about how few times we even see Joe Biden. There’s already such an imbalance on a visibility level and exposure level for Trump. Part of me just hopes that people are so tired of it that they want a president who will say, “I’m not going to talk for the first year.”

PORTMAN: It’s exhausting.

JOST: “Through the year, I’m just going to work. You’re going to see little positive changes, but I’m not going to talk about any of them. Go about your lives.” Like a gap year for a president. I think that’s a great concept right now.

PORTMAN: Everyone needs a cleanse. I’ve heard people say that making Trump funny, or even seeing someone likable like Alec Baldwin playing him in a funny way, can weirdly help him. Do you ever feel concerned about that? Is there something about comedy that softens a person’s persona?

JOST: I’ve definitely thought about it. It starts driving you crazy a little bit, because I don’t know what the solution is. First of all, it’s not as though Alec plays him as a lovable person.

PORTMAN: No.

JOST: As we’re thinking about the fall, part of me wants to figure out the most interesting way of doing Biden, because that might be the more important piece. If a take on Biden feels fresher than Trump, there’s power in that.

PORTMAN: Is there anyone you’re nervous about having read the book?

JOST: I wanted to reread it and think, “Am I being unfair to anyone in the book?” There’s a whole chapter about when I go to visit Google and I have a very elaborate, I would say, altercation-slash-physical injury there. I named the people who work at Google who essentially set me up for failure. I really went back and forth about whether I should name them or not. I was almost never more confident in any decision in my life than I was to leave their names in, because every time I reread that chapter, I became viscerally angry again. If people listen to the audiobook, they will hear more anger in my voice than they’ve heard about anything else during that chapter. It was so crazily negligent from the world’s largest company, and so physically endangering to me. It blew my mind that people at a company like Google could act like that.

PORTMAN: Oh my god.

JOST: I’m probably nervous for Lorne to read it, too, just because he’s my boss and he’s Lorne. I haven’t given him a copy yet, probably because I’m nervous.

PORTMAN: Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you wanted to add?

JOST: Do I have any questions for you, you mean?

PORTMAN: No. [Laughs.]

JOST: I actually have a list of 25 that I prepared.

PORTMAN: Okay, next time I need an interviewer, I’ll definitely call on you.

JOST: I would happily volunteer.