heaven is a prison

Cleanness Author Garth Greenwell Interviews Mark McKnight About His Daring, Dirty Pictures

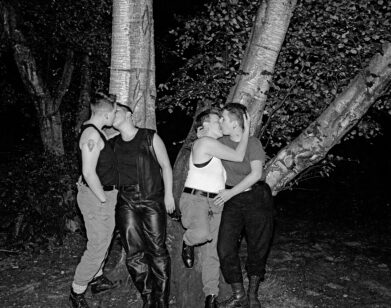

I first encountered Mark McKnight’s photographs in the spring of 2019, when I was invited to write an essay on his work after he’d won the Aperture Portfolio Prize. I was immediately taken by his stark, yearning black-and-white images. Shot mostly with a 4×5 view camera, McKnight’s photographs reference the history of the medium—much has been made of his relationship to modernist masters such as Edward Weston and Minor White—while at the same time radically renovating it in terms of style and subject matter. McKnight’s photos feature friends and lovers from his Los Angeles queer community, male bodies of a kind—large, hirsute, nonwhite—typically excluded from canons of beauty. He often insists that his choice of subject is fueled less by ideology than by Eros: he photographs the bodies he desires. In late 2019 and early 2020, McKnight shot a new series of photos in the California desert that daringly extends and deepens his exploration of sex, desire, and place. McKnight photographs sex—including sadomasochistic and fetishistic sex—in a way that complicates simplistic notions of pleasure and pain, dominance and submission. In their exploration of ambivalence, his images suggest a rich and nuanced—I want to say novelistic—approach to intimacy. The series makes up McKnight’s first photo book, Heaven is a Prison, which won the 2020 Light Work Photobook Award and is published this month by Loose Joints.

———

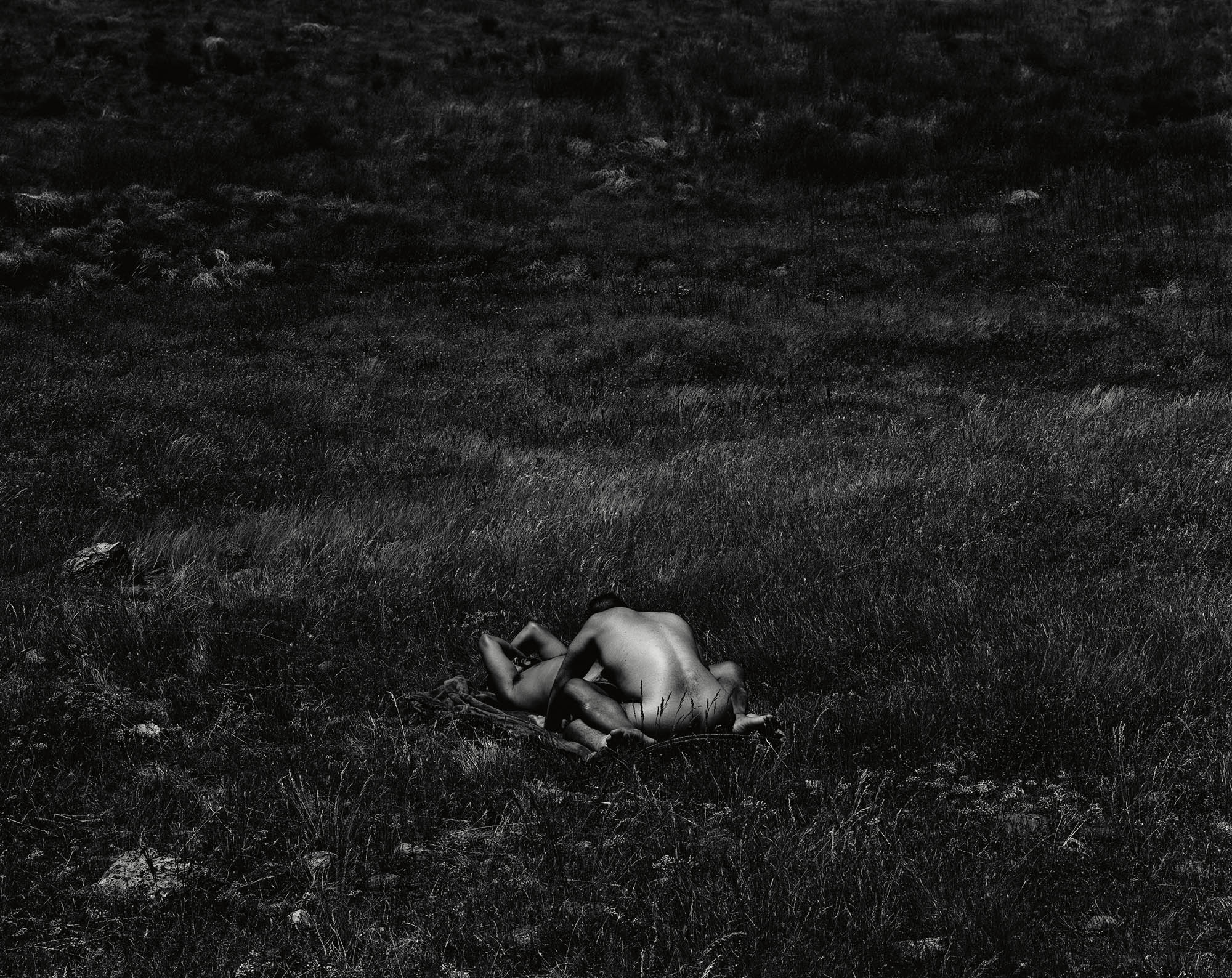

GARTH GREENWELL: Your book intersperses land- and skyscapes with explicit images of two men having sex in that landscape. How did the project come about?

MARK McKNIGHT: Doing a book is actually out of character for me. I’m usually an artist who makes work for the wall. But, in this case, I had started a body of work that I knew needed to be its own discrete thing, an object, a project unto itself. I knew I wanted to do a book of images of sex and landscape. So it was really fortunate, after I won the Aperture Prize, that the publisher reached out to me. Weirdly, I had a design concept in place before the majority of the pictures were even shot. The book is hardcover, and it’s wrapped in this cloud image, which you have to tear open. In order to access the book, you have to liberate the content.

GREENWELL: Why was that important to you?

McKNIGHT: There’s something about photo book people. They love the exquisite object. It’s totally fetishizing, which I love, but I also really wanted to fuck with that. I wanted to make a book that was this kind of pristine thing that you have to defile to access. I made the book thinking about the fact that if one wanted to keep the book immaculate, they would have to make a conscious decision not to open it. They would have to set it aside as some depressing, unrequited emblem of desire on their bookshelf. Actual appreciation of the content of the book is contingent on degrading, penetrating it. I think it mirrors the spirit of the book. It also makes the viewer complicit in my voyeurship. I like to think of the torn wrapper as a record of someone’s desire to see the material. It’s a gesture that was incredibly important to me, even if it’s lost on the majority of people who end up getting this thing.

GREENWELL: What about the actual subject matter? How did those images come about?

McKNIGHT: It’s two of my friends fucking in the high desert, in the chaparral of my adolescence, coupled with images of the landscape alone. For a long time, I’ve been making work that has sort of signaled and skirted desire and talked around it. It was purposeful, but I wanted to make pictures of ass-eating and piss play, of swapping spit and penetration, and insist that those things, too, could be graceful and elegant and essentially art. I wanted to insist on the acts themselves as being incontrovertibly beautiful and meaningful.

GREENWELL: My first and still dominant experience of your photographs—whether they’re of landscapes or naked bodies—is beauty. What is the role that beauty plays in your work?

McKNIGHT: Early on, I had a degree of shame around my desire to make things beautiful. “Beauty” and “beautiful” are bad words when you’re a 22-year-old art student. Now, though, I see beauty as a defiant position to take in what can feel like an increasingly cynical and ugly world. Also, beauty has historically been defined in terms of Eurocentric cultural standards. As a teenager, as a student in community college, and in art school, I was subjected to a canon of art history that did not mirror my racial identity, my physique, my sexuality, my desires. Up until really recently, it felt like all of the same, somewhat oppressive Eurocentric cultural standards around beauty were largely mirrored by mainstream gay and queer culture. I make what I make because it’s what I want to see, and I think that a byproduct of what I’m doing is problematizing certain histories or pointing at the embarrassingly narrow scope of art history. But that’s happening by way of my carving out a space for something else, which is really just something of my own. How we use beauty, what we insist is beautiful, is ultimately a reflection of our ethics, character, and values. Beauty is political. I guess I have a tendency to call things I appreciate “beautiful,” even if they’re conventionally not. And maybe that’s the place from which I’m always working. Maybe naming beauty for me is not just an act of defiance or opposition, but also a form of gratitude. It’s a reason to get up in the morning, to go make pictures and assign beauty through the act of seeing.

GREENWELL: Your work is often talked about in the tradition of the high modernists of American photography, people like Edward Weston and Minor White. That seems both true and inadequate. Are there ways that you feel you depart from that tradition? Or are there other traditions that you feel are important to your work?

McKNIGHT: Modernism is a totally appropriate reference, but I do feel like it’s one of many. As much as I’ve probably internalized the vocabulary of modernism, I am also sort of rejecting it—which is probably displaced daddy issues! The language surrounding modernism was so much about these notions of things like “description,” “purity,” and “truth.” The question I’ve always had is, “Whose truth?” Those modernist pictures routinely affirm cis white heterosexual subjectivity as objectivity, to the detriment of everyone else’s experience and identity. But I’ve also done things more in keeping with Surrealism than modernism, like trying to animate objects and anthropomorphize them. Most of what I’m doing probably has to do with the unconscious influence of the very first artwork I ever fell in love with, which was Jean Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast.” I mean, he’s this large, sensitive, hairy gentleman in a gothic cathedral who is surrounded by animate objects, lurks in shadows, longs for love, and cultivates roses. He’s basically my dream boyfriend!

GREENWELL: A minute ago, when you were talking about beauty, you linked it to shame, something that Heaven is a Prison explores and plays with. The photographs are not just explicit in dealing with sex; they also deal with sadomasochistic and fetishistic sex, including photos of piss play. What kind of resistance did you encounter making that work—external resistance, but I’m also wondering if there was internal resistance you had to overcome in exploring the “forbidden”?

McKNIGHT: When I was in the middle of making this work, a good friend of mine asked, “What makes these images not pornography?” I think inherent in that question was the presumption that pornography is something that I would actively try to avoid as a “fine artist.” The question really got under my skin, particularly because the presumption was somewhat accurate: I didn’t want to be labeled a pornographer. But in wrestling with that question, I came to the conclusion that—fuck, why not? What would be so bad about someone being aroused by an artwork? And what constitutes “pornography” in the first place? Also, why would that designation delegitimize the cultural value of what I’m making? I think sex is incredibly meaningful. These questions gave me a deeper license to make the work, to push myself into territory that was uncomfortable. I needed to make the pictures for myself.

My attraction to depicting sadomasochistic sex has to do with that. I wanted to make sometimes aggressive, sometimes tender photographs that spoke to the relationships between pain, pleasure, and intimacy as vehicles for transcendence. And going back to my interest in grace and form, I wanted to make images of these acts that were graceful and lyrical, so grounded in the austere beauty of the actual landscape that no one could walk away “shocked.” Or I hoped that their sense of shock would be with themselves for finding the acts so beautiful that it upended their notions of what constituted beauty. That’s the ideal.

GREENWELL: You mentioned that the men having sex in these photographs are your friends. What were the challenges of making those photos?

McKNIGHT: Not joining was the biggest challenge! These men are my friends, Chris and Nehemias. I’ve known Nehemias forever. He’s been in a lot of my photographs. Nehemias is an exhibitionist, which is why he’s so perfect for this work. There were definitely a few moments where the two of them would get lost in the experience of having sex and would completely just stop paying attention to any instruction that I was giving. In a couple of those moments, Nehemias would sort of wink and wave me over, as if it was time for me to join. But it didn’t happen, at least while we were working on the project. And not because I was afraid of crossing some kind of line of professionalism. They are 1000% not paid models. They’re just two friends in my no-budget art project who like spending time in the desert and wanted to help me. I think more than anything I didn’t join in because there’s something incredibly erotic about voyeurism. This project allowed me to be the creepiest version of myself, in a way that was completely consensual. The two of them jokingly christened me Master Daddy at a certain point, because I’m apparently extremely and uncharacteristically assertive under the dark cloth.

GREENWELL: Did you tell them specifically what to do?

McKnight: Yeah. I couldn’t be bothered with niceties because I was so busy focusing on the production of art. I would just be shouting these commands, completely asserting control over the kinds of sex they were having. I would just be like, “No, no, no, jam it harder, grab his throat, now kiss his neck. Okay. Lower, stay there.” It was like a tableau vivant: they would stand frozen in the position, and then I would walk closer, and I have this huge, clunky, large format camera and a tripod. And then I would spend somewhere between five to ten minutes focusing, changing a lens, making these obnoxiously minor adjustments, both to them and to the camera. Like sometimes I was waiting for a fly to land while they were holding these really painfully awkward positions and also begging me for a break because their legs were shaking. And I would just be like, “No, no, I need you to stay hard. Keep him hard. Okay. Spit on it.” Then I’d make a picture and say, “Okay, relax.” And they would inevitably fall back into the grass and release the tension in their muscles. Or alternatively, they would go hide under a blanket because they were getting sunburned, or in some circumstances they would just finish fucking each other while I stood there and watched, which became research for subsequent photographs.

GREENWELL: That sounds really awkward and uncomfortable.

McKNIGHT: And sometimes hilarious! There was one picture that I really wanted to make, this first-person photograph of Nehemias pissing into Chris’s mouth while he was upside down reclined on a rock. And the day I wanted to make this picture, I just couldn’t get it. We kept trying, but it was so windy. Nehemias ran out of urine. So I took his place, I disrobed, and then I was trying to awkwardly make the picture where I am sort of acting as Nehemias and my dick is at the bottom of the photographic frame and I’m pissing into Chris’s mouth, but of course I was holding this huge camera with two hands, so that meant I couldn’t aim. Plus, as I mentioned, it was windy. So Nehemias then came over and is holding my cock while I’m holding the camera and he’s aiming it at Chris’s mouth. And I’m trying desperately to hold steady long enough to make an image. And it was just a total failure. Like my urine blew all over all of us and we just devolved into hysterical laughter—I think because of the absurdity of my obsessive desire to make this image in spite of the circumstances. Chris, lying there covered in piss upside down, starts laughing and then none of us could stop. It was the most innocent thing and it was the most abject and also it was extremely intimate and really indicative of how committed both of them were to the work. Yeah. Thinking about that makes me want to call them and thank them again.