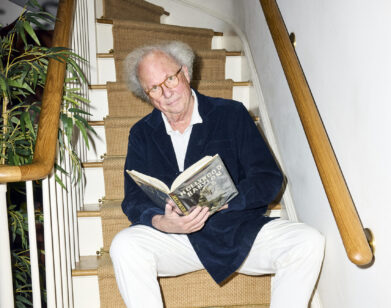

Chukwudi Iwuji

ABOVE: CHUKWUDI IWUJI AT THE LIBRARY AT THE PUBLIC THEATER, SEPTEMBER 2016. PHOTO: CHRISTOPHER GABELLO.

“When I was 10 years old living in Ethiopia, we had a black movie market because television there was so bad,” recalls actor Chukwudi Iwuji from his dressing room at the Public Theater. “People used to just exchange videotapes, and one of the videotapes that came to our house was Becket, the movie with Peter O’Toole and Richard Burton,” he continues. “I was obsessed with that film. It was a movie set in medieval times, a 10-year-old shouldn’t be interested in it, but I was obsessed.”

It is thanks, in part, to Peter Glenville’s 1964 biography of Thomas Becket, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury, that Iwuji became an actor. The son of Nigerian parents, both of whom worked for the UN, Iwuji spent his childhood in Africa before attending boarding school in Britain. When he was in his early 20s and studying economics at Yale University, he saw a post for a student production of Becket. “My girlfriend at the time said, ‘I know the director and he’s looking for his lead.’ So I auditioned and I got it,” he explains. Based on that performance alone, he was offered a scholarship to the Professional Theater Training Program at University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “That was from a movie in Ethiopia I saw as a 10-year-old,” he says with a laugh. “That’s why this business is crazy. It’s circles within circles.”

For the next two weeks, Iwuji is starring as Hamlet at the Public on Lafayette Street. Put on by the Public’s Mobile Theater Unit, the production distills Shakespeare’s famous tragedy down to its essentials: A nine-person cast performs in the round in a black-box theater for a 100 minutes; there is no backstage and no intermission. This austerity is for a practical reason—before coming to the Public, the company toured the play throughout the five boroughs, performing for free at 18 different locations including libraries, correctional facilities, women’s shelters, and community and recreation centers—but it is also extremely effective. In the hands of Iwuji, his fellow cast members, and their director Patricia McGregor, Hamlet feels relevant, sharp, and funny.

Although Iwuji is currently based in Harlem, New York (he moved in 2012 for a production of Richard III with Kevin Spacey), his next project will take him back to London. Starting in December, he’ll be on stage at the National Theatre in Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler directed by Belgian auteur Ivo van Hove (The Crucible, A View from the Bridge).

EMMA BROWN: Have you ever done anything like the Public Theater’s Mobile Unit before?

CHUKWUDI IWUJI: No. I have never experienced anything like this. I don’t know if there are many things like it elsewhere. It held a natural bit of trepidation for me going into it. You’re talking about going into maximum-security places, women’s shelters. My career’s been very much about places like the Ambassadors [Theatre in London] and the Public, where you know what to expect of your audience. So that x-factor of the unknowable was something that was a bit frightening for me, but everyone I had spoken to that had done it before and [the Public’s Director of Special Artistic Projects] Stephanie Ybarra all promised that if you open yourself up to it, it will be life-changing. And it has been. That’s no exaggeration. I’m not throwing that phrase around easily. It really has.

BROWN: Had you done Hamlet before?

IWUJI: After drama school I moved back to London. The week after I arrived, my wonderful agent—who’s still my agent to this day—got me an audition for the Royal Shakespeare Company. I got hired and the first ever show I did with them was Hamlet with Sam West as Hamlet. I played Cornelius. He didn’t make it into our draft. He’s one of the ambassadors, but not the one that speaks, the one that glowers in the corner. It’s probably the smallest named character in all of Shakespeare’s canon. [laughs] I played him and not the Player King, but the Prologue in the play with the Player King, so it was a long season, but it was great for me because it was a huge learning curve. I wouldn’t say that’s when I wanted to play Hamlet—I think I’ve wanted to play Hamlet since I started acting —but that was when I started the actual constructive imagining and building and contemplation of the role, by being with that for 15 months, basically. We did that and another play, but we pretty much did that for 15 months. So Hamlet has been very much something I’ve wanted to do for a long time, and I won’t lie, I thought I might have missed it. I thought it might not happen. You don’t really audition for Hamlet; Hamlet is one of those roles that a director or producer decides you should do it. First they get the Hamlet, then they start deciding on the play. So it didn’t seem like it was going to happen and then, just as it often is in this business, out of the blue, you’re having a drink with Stephanie Ybarra and she starts contemplating. Then I had a sit down with [the Public’s Artistic Director] Oskar [Eustis] about something totally different, and he started contemplating and the two of them got together and suddenly there was a phone call saying, “Do you want to do Hamlet?”

BROWN: With a play such as Hamlet, even if you’ve never seen it before, there are so many lines that stand out because you’ve heard them somewhere else. How do you get back into what the text really means and prevent it from being almost a series of catchphrases?

IWUJI: Someone asked me this; I think it was at the Public Library. One of the attractions of Hamlet to me was I never understood what the big deal was. [laughs] I knew it was a great play, I knew it was a great character, but I often wondered, “Why do people keep going on about their role? Is it this thing we do of giving ourselves leeway, making excuses before we’ve done it? What’s the big deal about this guy?” Hamlet’s speeches, famous as they are, are very clear as to what he’s saying, at least it seems to me. It’s not as complicated as Aufidius [in Corialanus] or I did Edgar here in Central Park [in King Lear in 2014], and those speeches are just crazy. So I said, “What’s the big deal?” Then I started to do it and I started to study it and I started learning those lines and coming to terms with those lines, and you realize that in every one of those five great speeches, he goes through every emotion and then tracks back and then some. It literally exhausts you. It pulls you inside out to make sense of those speeches, and by making sense, I mean connecting viscerally, mentally, and spiritually with them. A woman asked me that very question and I didn’t actually have an answer, I sort of figured it out as I was talking to her. For me, it seems that—and you can relate this to all acting—at first you make sense of the words for yourself. Don’t think about it in terms of the speech; think about it in terms of, “What am I saying here?” Then the second level is, “How can I communicate what I’m saying to you, the audience? Every single one of you.” Then level three is, by saying this, this language is doing something to me emotionally, because in life, everything we do has an emotional content to it, whether it seems the most frivolous thing or the most heartbreaking thing, there’s a content to it. On stage, it’s being alive to all that, so through that emotion—of which these speeches delve into like no character I’ve ever played—how do I make sure I drive through that to make sense of what I’m saying to you—connect with you? So when you do those three levels, there’s no room for you to think about it as a speech. It’s all about being in the moment and trying to do those three things all at once for the audience. Of course I think of them as these famous speeches, because I know they are, but in the execution of them, you have to go through what I just explained to you, and you lose its intellectual appeal and becomes about something very visceral and immediate. That’s what stops it from becoming just the speech, and why I hope you feel like you were there.

BROWN: One thing I particularly enjoyed about your production was that it was very funny at times. I didn’t really realize how cutting Hamlet was as a character. Those aren’t things I associate with Hamlet.

IWUJI: The play is very funny. And all good writers across the board, if they’re dealing with real tragedy, they will give you comedy in it. And if they’re dealing with real comedy, there will be tragic moments in it. I’m going to be criticized by lots of “scholars,” but I think Shakespeare’s best comedy often appears in his tragedies, actually. Not necessarily in his comedies. I think Hamlet is a very funny play—Hamlet is riddled with wit. I think Hamlet, as much as he loves his privacy and is kind of an introvert, he’s a very functional introvert. When he has to be out, he can be out with people. It’s something our director Patricia [McGregor] did brilliantly, going back to the basics of what are the relationships of these people? Because we know what happens with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, people forget that for us to get to that tragedy, for us to get to the man that will arrange for his friends from childhood to be murdered and for that to be a tragedy, we first have to see how they were before they start double-crossing him. They were really good friends. You have a great comedic moment when they first meet. I think part of the sadness of Hamlet is given different circumstances, this guy had the capability of being something really great and not ending up poisoned on the ground.

BROWN: I liked that the book Hamlet was reading in your production was Nothing Personal.

IWUJI: That was [director] Patricia’s choice. [laughs] It’s a James Baldwin essay, as you know. She associates him very much to this. When I said, “Yes, I’ll do Hamlet,” I had a photo shoot. As you’ve seen in the posters, there’s this guy with a hoodie and a lighter—we went kind of crazy. I was in a tank top and I had a spray can and I was suddenly going, “Wait a second. What is this Hamlet that she wants to do?” And I had a conversation with her and I actually said, “Patricia, are you sure I’m the right Hamlet for you?” Because it’s very clear a theme running through this is Black Lives Matter, a theme running through this is the anger in America, in the world right now. And not that I don’t associate with that, but I’m here going, “My background is that I was very lucky. I grew up in Nigeria, my parents worked for the United Nations, I went to boarding school, I was head boy. I went to Yale. I get all this stuff, but am I the angry guy you want for this?” And she said, “The very fact that you’re asking that question, the very fact that that is your background, that you are who you are, makes you the right guy for this.” The whole point is that no one’s born a murderer. The guy that ends up taking up a rifle and sniping a policeman, as late as two days before that, probably, most likely, wasn’t planning on becoming that person. We’re talking about what is it in society, or in the case of Hamlet, the betrayal of the people you trust and the people you love, that can drive you—a sane person, an upstanding member of the community—into the person that starts throwing bricks through windows. We have the beginning with a Hamlet asking, “Can I go back to school?” That he wants his books, and by the end of it we have this avenging force, and the journey is him saying—as is the journey, I think, of a lot of disenfranchised people—please don’t let me become this thing. Don’t let me become this person. [With] James Baldwin, a big part of his life was about inclusivity, was about acceptance. He wasn’t really accepted by the Black Panthers, he wasn’t really accepted by the movement. He embraced Martin Luther King Jr. and the peaceful way. Then Martin Luther King got killed. This is a guy who is trying to write that the way forward is to believe we can do it together and not to be separate, and yet society wasn’t allowing that to be the case. So it was very important to Patricia to have his essay as that idea of disillusionment—that idea of trying your best and not being able to pull it off because of betrayals.

BROWN: You performed in different venues around the five boroughs. Where was your first performance?

IWUJI: It was at the women’s shelter in Lennox Hill. It was extraordinary. For me—again, I’m not speaking hyperbolically—it changed me as an actor and consequently probably as a person, as much as art and life embrace each other. I went home and I rarely do this, but I wrote a sort of meditation on Facebook on that performance and being in that room with these women and doing Hamlet and watching these women totally connect with the text and totally connect with the story and feel like the story was really happening. With all their troubles, they connected to it because the themes made sense to them. I remember starting “To be or not to be,” and about five women chimed in with, “That is the question” in perfect iambic. That happened two or three times in the tour. In prisons—in Riker’s. Maybe they’d studied it in school, maybe, like you say, it’s catchphrases they’ve heard, but they got it. In that women’s shelter, when you’re talking about suicide—just giving up—you had these women calling out, “Don’t do it.” And it was when I realized that it is so much more interesting to be a storyteller than to be an actor. We have this idea of acting something, when at its best, acting or performance is a communion. Those women made me really feel like I was just a storyteller and it was easy. It wasn’t all those other things we worry about: “How good am I?” It was: “I’m going to tell you this story, I’m going to share it with you.” They gave me so much back, and I sort of rode the wave of that. That is a theme that existed throughout this tour, going to these venues. Till you’ve said, “To be or not to be” staring at the eyes of a guy in Riker’s who’s not going to see freedom ever again —or might be being shipped to some high security prison in Alabama the next day, which was the case with one of the prisoners—till you’ve said, “Should I end it now?” to someone who is probably going to be asking that question of themselves on a daily basis for the rest of their life, you haven’t done that speech. Whatever it is you saw last night when you came I hope is a continuance, an amalgam, of those experiences, of people that really need these stories. That’s what I meant by it changed me as an actor and it changed me as a person. The concept of generosity through what you do and who you are has taken on a whole new meaning for me. It changes why you’re doing this, why you’re doing things.

BROWN: Obviously there are many differences between performing in venues like Riker’s and community centers and school gyms and performing in a theater—you know what to expect in a theater, the light is generally in your eyes so you can’t make eye contact with the audience. People being vocal in their reactions isn’t something that generally happens in polite theater. What was that like?

IWUJI: It was amazing. And I wish “polite theater” did it more. It’s raw. It’s what it would have been like in Shakespeare’s time. Performing at the Globe or on the road, people shouted out comments, whether it was a knowing political comment or a bawdy comment. When you’re in the middle of Hamlet being poisoned and a woman shouts out, “Help him Horatio.” Or I’m about to maybe kill Claudius and someone screams, “Don’t do it.” Or, “To be or not to be,” and I have the strap on my arm and a woman buries her head in her hands and just starts moaning in the front row: “No, no.” We’re spoilt. It changed what performance is. There’s a side of me where I would love for “polite” audiences, as you put it, to be less polite, to be more vocal, to be more reactive, to understand we’re in it together. Which is kind of why I like the set-up of the round. To work around and be successful in a round configuration in the theater, you have to connect with everyone. One of the goals I’ve set myself is to make eye contact with everyone in the audience at least once. You can’t stop in any one position for too long, and just that physicality, that need for that, it’s so all-inclusive. If we could extend that to vocal responses, bring it on, it’s beautiful. Just as someone will yell out, “Don’t do it,” you’ll hear a sob. You’ll hear someone not afraid to wail. And you’re connected. And when you feel connected, it just isn’t as hard. It’s much easier, because we’re all in it together. So the answer to your question is I wish we did that more.

BROWN: I wanted to talk a little bit about your background. You mentioned earlier your parents worked for the UN. Were they like, “Oh sure, become an actor”?

IWUJI: Being African parents especially. [laughs] I used to act as a kid in Nigeria—I did nativity plays and things. Then I acted in junior high. I was Joseph in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. Then I went to boarding school in England and, of course, they separated you between the artists and the athletes. I loved sports, so acting died and it was all sport. But I always used to get in trouble, because after lights out I would sneak out to watch things on TV. The Oscars was a big one, and that would happen at midnight. Not because I was there saying, “Oh, I’m going to be an actor.” But there was an aspect of something that just draws you, and you don’t quite now why. So fast-forward to my A-Levels and I genuinely didn’t know what I wanted to do. I’d been accepted in a couple of places in English universities—we were going for Oxbridge—but I knew that in America you had this magical two years of “liberal arts” where you can do whatever you want. Maybe that side of me I hadn’t quite identified understood that if I was ever going to follow whatever this dream was, it would be through that space, that time, in America. So I sat down with my dad and I said, “Dad, I think I might want to go to university in America.” And my dad being Nigerian and from a British colony, believed that the best education was actually in England, but he did defer to the Ivy League [universities]. He said, “If you’re going to go to America, two stipulations: one, never California”—his belief was that you’d be on the beach all day in California—”and secondly, you have to get into an Ivy League.” He said, “If you get into an Ivy League [university], I’ll let you go to America.” I think it was the most expensive bet of his life when I got in, but he was so proud. So I got to Yale to do economics—I graduated with a degree in economics—and while I was at Yale, I started doing plays. After I did my second play, the head of acting offered me a scholarship to the conservatory in Wisconsin that he was about to take over. It took me a whole semester to write to my parents because I was terrified of telling them that, after all this money they spent, I was going to become an actor and go to drama school. I still have the letter they wrote back to this day, in which they essentially said, “We’re proud of you. We’ve given you everything to make the best of your life. You’ve excelled; you’ve done well. After university, it’s time to live the life you really want. We’ve done our responsibility and now it’s up to you. Congratulations on drama school.” And that was it. And my dad, from someone who I can’t remember staying awake through a movie, became a movie buff—Cagney, Bogart—he just started watching all of these films—Turner Classic Movies. He’s actually flying over to see Hamlet because he was saying, “I’ve missed your last couple of plays.” My mum, god rest her soul, saw everything that I did, and thank god for that. Without those people around you saying, “You’re going to be fine,” this business is virtually impossible. That was the story. My parents were very traditional Nigerians who wanted doctor, lawyer, teacher [children], but when I actually had a dream and I presented the dream to them, they were 100 percent supportive.

THE PUBLIC THEATER’S MOBILE UNIT PRODUCTION OF HAMLET IS ON AT THE PUBLIC THEATER IN NEW YORK THROUGH OCTOBER 09.