Beyond the Pale: Christian Lander Interviews Carrie Brownstein

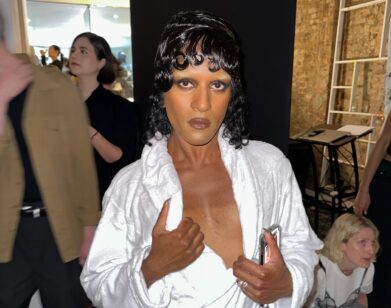

ABOVE: CARRIE BROWNSTEIN. IMAGE COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER HORNBECKER/IFC

As far as cult TV shows go, Portlandia may be the unlikeliest of the little engines that could: a geographically anchored sketch comedy whose only recurring motif is Portland itself. And yet, for its lovingly extraverted renditions of the modern American bohemian—from gauge-sporting cyclists to concerned restaurateurs who only consume cage-free—Portlandia resonated with cardigan-wearing viewers across the country. The reason? For stars Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein, it’s a labor of love.

“We’d been doing [sketches] for five years before IFC decided to make it a show,” Brownstein told Interview‘s Esther Zuckerman in 2011. At the time, comedy was relatively new ground for the Seattle, Washington native, better known by fans as one-third of the prolific indie rock powerhouse Sleater-Kinney. But as a veteran of the stage, Brownstein caught on quickly. “It was the same way you would form a band and just play for your friends,” she explained.

If flexibility is a virtue, then Brownstein, 38, is nothing short of a virtuoso. Away from the small screen, she plays guitar for the critically acclaimed group Wild Flag. Elsewhere, she writes for The Believer and Slate—all in addition to writing a memoir, soon to be published by Random House. On Portlandia, Brownstein assumes the identity of the everyman—literally—with ease, swapping swigs, outfits, and on occasion, gender, in her show’s wild and affectionate send-up of the bougie masses.

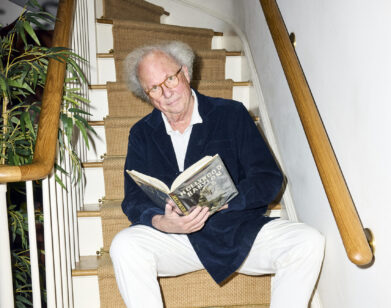

In choosing a foil for Brownstein’s satire, we appointed the efforts of none other than author Christian Lander, the creative mind behind New York Times bestseller Stuff White People Like: A Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions. Lander, 33, enthusiastically accepted the offer, and Interview shared a phone call with them at their respective homes (Lander in LA, Brownstein in Portland) on a mild December afternoon to discuss privilege, “anti-ambition,” dreadlocks, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, authenticity, rock stars, the new Portland, and—we couldn’t avoid it!—hipsters.

JOHN TAYLOR: Carrie, why is it so easy to put a bird on it?

CARRIE BROWNSTEIN: [laughs] Well, it’s definitely easy to put a bird on it in the sense that it’s such a shorthand for art. It’s a very easy thing to draw, I guess.

TAYLOR: Christian?

CHRISTIAN LANDER: I don’t know… I guess I don’t put a lot of birds on stuff.

BROWNSTEIN: I don’t put birds on stuff either, but I’m very susceptible. The charm is so immediately apparent that I’m often tricked.

LANDER: I think what I love so much about [Portlandia] is that I see an undercurrent of a criticism of privilege. Specifically, middle-class privilege. Do you get a lot of questions about that?

BROWNSTEIN: We actually don’t get a lot of questions about that, but I do think that’s something that I think about. I think about the notion of entitlement a lot. And living in Portland, which is a predominantly white city, the privilege and the luxury to be able to obsess over a certain kind of minutia, that I think, if you did not have that privilege, would never be bothersome. When people are worried about whether “local” means 100 miles, or 50 miles, or 10 miles from a grocery store, I just think, “Wow. What a privilege it is to have that as a major concern in your life.” As opposed to, “Can we afford food tonight?” Sometimes I’m just shocked at what becomes concerning in these kind of communities. I don’t think we intentionally write the show with that in mind, but I think to completely disregard that would remove any kind of core from the show. I think the awareness of it permeates the characters, and the narrative. Otherwise I think the show would be crap. [laughs] Or dishonest.

LANDER: Do you think that in Portland, there’s a recognition of this? Or are there people who recognize it and say, “I know, but what am I going to do?”

BROWNSTEIN: I think the latter in Portland. The Northwest, to make a generalization, is a fairly sensitive populace. Slightly self-conscious, and very self-reflexive. I grew up outside of Seattle, and have lived here my whole life, and I think that there is a culture of questioning, and guilt. Almost an “anti-ambition.” Like, an awareness, and then a subsequent guilt. But sometimes that progressive, liberal guilt is really obnoxious, too—in some ways, I think it’s better to just own it. It’s weird, that actually, the acknowledgement of privilege or the enactment of guilt can be as obnoxious as anything else. It’s a never-ending rabbit hole. We’re really in a rabbit hole right now, with this conversation. We’re just spiraling down into the void.

LANDER: “Anti-ambition.” What do you mean by that?

BROWNSTEIN: I’ve noticed that as someone who has done music and creative things in Washington state and Portland, to kind of toot your own horn, or admit, “I’m going for it. I’m hustling,” is not exactly the norm. Which is weird, because you go to New York, or LA, or anywhere else, you’ve got to be gunning for it—and you should be—you’re part of a fast-moving stream of other people who are really ambitious. People move here to work less. So, to say that you’re hustling all the time, and going for it, is kind of a little bit against the grain here.

LANDER: I wanted to ask you—you went to Evergreen State College. And that’s pretty much the most liberal of the liberal arts colleges in the world. Am I right?

BROWNSTEIN: Yeah, that and Hampshire [College] are very similar. Like, experiential learning, qualitative grades—really, no grades—but, qualitative evaluations.

LANDER: Can you walk me through a little? I want to know from the inside what going there is like.

BROWNSTEIN: I think that there are two Evergreen experiences. And I’m not sure what it’s like now, but supposedly in the same way that alternative and mainstream culture have totally been conflated in the last decade, Evergreen has now become a much more, like, normal state school. There was a time where only environmentalists and hippies were probably going there, and it was very counterculture. And now if you’re a jock growing up in the suburbs of Seattle, you might actually also go to Evergreen.

LANDER: Oh no! It’s gone mainstream?

BROWNSTEIN: [laughs] I had a pretty normal college experience there.

LANDER: Did you have any experiences that seemed normal at the time, but if you look back you’re sort of like, “That was the most liberal, hippie thing I’ve ever seen in my life?”

BROWNSTEIN: Well, just sort of a sad hippie thing was this young kid, so earnest, and so ready to transform his sort of East Coast, upper-middle-class upbringing into a really die-hard, well-intentioned progressive lifestyle, or something. We were in a seminar, which is kind of an offshoot of the lecture, and you go in a small group and you discuss the lecture and the reading materials, and his hair was slowly turning into dreadlocks.

LANDER: Oh, no.

BROWNSTEIN: He had, like, a mason jar of something that was really green and garlicky that he had made at home, and he just kept saying the word “Tay-o.” Like, “Tay-o, tay-o, tay-o…” until finally the professor was like, “You know it’s pronounced Tao, right? It’s just Taoism. It’s not ‘Tay-o-ism.'” And it was just very sad. It was just the sad confluence of earnestness right up against ignorance and naïveté.

LANDER: [laughs] Please tell me that he cut off the dreads after that experience?

BROWNSTEIN: He didn’t cut off the dreads, but he was definitely chastened by the experience. He didn’t speak up for a while. I think even then it was just too much for me, the wholehearted eschewing—like, people who didn’t wear shoes. I thought, you know, anyone who grew up poor would not decide, “I’m just not going to wear shoes.”

LANDER: Or anyone who was worried about a tetanus infection.

BROWNSTEIN: Yeah. Shoes are a great invention. They keep us from stepping on nails. Your feet stay clean, and warm and dry.

LANDER: A lot of the stuff you guys make fun of on the show, like people who make their world needlessly more difficult, rejecting things… why are we doing this?

BROWNSTEIN: That’s a good question. I think [we] as people struggle for what is meaningful in our lives, and I think that modern, contemporary life is as easy as it’s ever been, for many, many people, and the amount of physical exertion, for most people, is less than it’s ever been. I think that there is something about the ritual of making things more difficult that people find meaning in.

LANDER: Did you see the movie Jiro Dreams of Sushi?

BROWNSTEIN: I didn’t see it. I noticed in on Netflix and should watch it. Fred [Armisen] saw it and loved it.

LANDER: It’s this amazing [documentary] of a guy finding meaning through his work. His [goal] was to get better and better, every day, at this one thing. It’s interesting to think, one of the ways we’re trying to find meaning, especially in this artisanal stuff, is to try and find it through a physical, tactile connection with something.

BROWNSTEIN: I think it all just keeps coming back to people trying to grasp something that feels meaningful and authentic. Whether they’re purchasing those things, or starting to make them themselves.

LANDER: Do you think that we’ve ever been more obsessed with authenticity? [In] the obsessive search for truly authentic Chinese food, or sushi, the presence of another white person immediately destroys all authenticity that that restaurant once had. Why? Do you think it all stems from this desire for meaning and belonging, or, are we just getting more pretentious?

BROWNSTEIN: It seems like both. I think that the intentions are genuine in the search for authenticity, but it can tip over into absurdity so quickly. I just start to wonder, like, what authenticity even is, and whether we can even start to define it in such a globalized world. I was just reading that article in The New Yorker about those underground restaurants…

LANDER: The supper clubs? Yeah.

BROWNSTEIN: I mean, that’s such a perfect example. Like, an actual restaurant is no longer an authentic way of eating food. It used to be okay to just go to a restaurant and get a table, and if it was a good restaurant, and you liked it, then that was enough. And then it was like, “Well, if there’s not a huge wait… we can’t go to a restaurant that takes reservations. That’s too easy. We have to go to one that doesn’t take reservations, and you’ve got to wait an hour, this must be really good,” and now it’s like, “Well, if I’m not on an e-mail waitlist of three months to go to some undisclosed location…” It just seems like, wow, what a difficult way to eat.

LANDER: Is the food scene now the new indie-rock scene? Everything you’re describing is sort of like the older days of indie rock, where you had to go through the difficult channels to find the underground shows. Do you think that’s been replaced with food?

BROWNSTEIN: Your analogy is totally apt. I think you’re right. Especially when you put it in that way—like, with indie rock, that inherent snobbery was, if you had heard of the band, then they were already too big. If you played a venue that was bigger than a certain size, or [that] wasn’t in a basement, then you had sold out. And it does kind of seem like that’s starting to happen with food. Chefs are the rock stars of today. They’re definitely celebrities.

TAYLOR: So, does that mean indie rock is dead?

BROWNSTEIN: I think it’s still going.

TAYLOR: I’m relieved.

BROWNSTEIN: Good.

LANDER: But if it is dead, at least you can get some really good pork belly. [all laugh]

TAYLOR: Carrie, do you own a copy of Stuff White People Like?

BROWNSTEIN: I don’t own a copy of that book, but it’s funny—I’ve given the book as a gift, and I read the blog. Are you offering to send me one?

LANDER: I am! [pauses] I was just wondering, is Portland really this last chance to have an urban, middle-class life?

BROWNSTEIN: I mean, it kind of feels that way in terms of it kind of feeling like a Mecca, but it can’t be the final frontier because the goalpost keeps changing. And some other city will crop up, as having a sense of possibility. You know, I feel like Pittsburgh is a good example of a place that could have just as easily become the next Portland, in terms of people repurposing spaces and transforming a depressed economic area into first living-slash-work spaces. Portland’s a little bit of the poster child for that right now, but I have a feeling it’s certainly not the last place that’s going to go through this transformation.

TAYLOR: So we can quote you: “Pittsburgh is the new Portland.”

BROWNSTEIN: Yes, please quote me. [laughs]

TAYLOR: In closing, who is more hipster, Christian or Carrie?

LANDER: She’s in a cool band, she wins.

BROWNSTEIN: I think it’s Christian! Come on. I think his book is the definitive hipster book. Just the fact that we’re having this argument—we’re both going to be—we’re canceling each other out. [Taylor laughs] I’m revoking. I don’t even know what a hipster is.

SEASON THREE OF PORTLANDIA, STARRING CARRIE BROWNSTEIN, PREMIERES TONIGHT ON IFC AT 10 PM. CHRISTIAN LANDER IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL WORKS OF NONFICTION, INCLUDING STUFF WHITE PEOPLE LIKE (RANDOM HOUSE).