Caitlin Moran’s Girl Uninterrupted

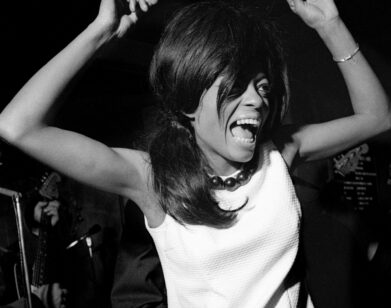

ABOVE: CAITLIN MORAN

Johanna Morrigan, 14, lives in a Wolverhampton council estate with her parents, four siblings, dog, and a growing sense of shame after badly embarrassing herself on local TV. She is chubby and twitchy, prone to compulsive masturbation, dangerously intelligent and equally restless: something’s got to give. And something does, when she reinvents herself as Dolly Wilde (named, of course, after Oscar’s fabulously witty niece), dons a top hat, and begins writing reviews for a London music rag. Suddenly, she is a Lady Sex Adventurer, getting drunk and sleeping with nearly as many musicians as she infamously eviscerates in print. Her life is literally sex, drugs, and rock-‘n’-roll—and living that reality proves altogether different from Johanna’s fantasies about it. (Note: you may be laughing too hard to notice Johanna is learning a lesson until after it’s already been absorbed.)

It’s not a secret that Johanna’s life shares a number of biographical details with that of her creator, British newspaper columnist Caitlin Moran—anyone who read Moran’s searingly funny memoir-cum-polemic, How to Be a Woman, will remember that Moran herself got her start as a precocious music reviewer, for Melody Maker. When we met Moran in the “Narnia room” at her publisher’s office in downtown Manhattan to discuss the novel, she was dressed not unlike she might have been back then—flannel shirt, cutoff jeans, tights, and boots—and she immediately swept us into a big hug.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: I so wish that I had a book like yours when I was a teenager. Either you and I were very different from every other teenager, or else books about teenage girls aren’t very honest about what they’re really like.

CAITLIN MORAN: There’s so many girls like us, that’s the thing. I’ve spent all my life thinking that I’m weird, and I must be the only one who’s kind of bleeding and wanking, with [gestures to her hair] hair, and have dreams of being noble and not just suffering. When I did How to Be a Woman, it felt like kind of a risk to be like, “Well, these are the things I do.” But when that book came out, everyone was like, “But no, I’m like that too!” You suddenly realize that rather than being a single, weird, lonely, freaky lady, that there’s millions of us—there’s a nation of girls like us, and it’s a beautiful thing to connect.

SYMONDS: People talk a lot about how fragmented “fourth-wave” feminism is, and what that might mean. In reality, I think the keystone of fourth-wave feminism might be women finally being allowed to say how it is they really are—and not to have these shameful secret lives.

MORAN: Well, yeah! You just see that now suddenly in the last couple years. Suddenly all these girls are doing all this stuff, like Lena Dunham was doing Girls at the same time that I was writing that book. Sarah Silverman, Amy Schumer, Broad City, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Melissa McCarthy, FKA twigs, Nicki Minaj, the kind of stuff Miley Cyrus is doing—there’s a brilliant shamelessness. “We are going to talk about sex, we are going to talk about our disgustingness.” This whole idea that women must be clean and sterile and meek and not opinionated and grateful has just been completely blown apart in the last three or four years. You’re just not seeing that anymore.

SYMONDS: And they’re funny. The idea that to be a feminist, you have to be staid, is ridiculous.

MORAN: Anytime you say something like “a political movement,” it has to be prim and proper and correct and factual and dry at all times. And of course you’re going to limit its appeal. Of course no one wants to sign up for that fucking revolution.

SYMONDS: [laughs] Yeah.

MORAN: “Hey, you know what, we’re actually talking about genuinely changing things for the better. Changing the psyches and the options of women, and it’s going to be fucking brilliant! You’re going to go out and meet a load of really brilliant girlfriends, and get completely slammed, and wear whatever the fuck you want, and just know that the future’s going to be better than the past and live a life free from shame.” And we’ll start off talking about the revolution and end up talking about David Bowie and which one of The Beatles we would’ve liked to have sex with.

SYMONDS: I don’t think there’s any conversation about the revolution that can’t end with talking about David Bowie. [laughs]

MORAN: Yeah, exactly! Like the amount of times I get asked in Q&As, “If you’re feminist, can you wear makeup?” Basically, my belief is that if David Bowie can do it, I can do it. And secondly, you can wear makeup for whatever fucking reason you want, but I want everyone to know the reason I wear makeup is I’m not trying to look sexy or beautiful or flawless. I’m trying to look like a bird: the puffin. Have you seen puffins? They’ve got these big beaks, they’ve got the black thing there, with the color and stuff?

SYMONDS: [nods]

MORAN: When you’re wearing makeup, the idea isn’t always to like some kind of airbrushed beauty queen—if you want to, fucking go for it, but you can look like something else instead. That’s why I love goth girls in makeup. They’re not trying to look beautiful, and sexy and pretty. They’re trying to look fierce and deep and dark.

SYMONDS: To bring it back to your book: for girls, being a music nerd is a weird shortcut to acceptance they don’t tell you about. When you’re a chubby, nerdy girl, all you have to do is memorize indie bands like baseball cards, and then at some point you’re allowed in the club.

MORAN: Literally, you just come in and go, “I want to talk about Spiderland by Slint,” and they go, “Welcome, come on in!”

SYMONDS: But as Johanna learns, at some point you might realize that although what brought you there is still awesome and amazing, maybe that’s not a club you necessarily want to be in, either.

MORAN: Then you realize you have to be in your own club! I so wanted a boy to write a song about me. I wanted to go out there and meet boys in bands. I didn’t want to fuck them—maybe a couple of them, but that wasn’t the whole idea—I just wanted them to write a song about me. I wanted to be a muse. It took me 10 years to realize that instead of waiting for someone to write a song or book about me, I should write one myself.

SYMONDS: Yeah.

MORAN: I think so often when girls think that they want to be muses, what they actually want to do is to be the artists. I was watching Anthology by The Beatles with my daughter, that early footage of the girls screaming at The Beatles, and I was just thinking, “I don’t think you’re screaming because you want to fuck them. You’re screaming because you know it’s going to be a long time before girls will be able to do what those boys are doing onstage—before a group of four teenaged, working-class girls will be able to be on that stage and strike the world like a colossus. It’s going to be another 40 years before working-class girls get the same chance that The Beatles have got.” And then I just burst into tears. All those girls in the ’60s should’ve known what revolution is like but never got to where we are now. And then I had a glass of wine and calmed down.

SYMONDS: [laughs] Something I really loved in the book is the moment when Johanna’s editor, Kenny, gives Johanna that very wanky speech: “You’re not a fan, you’re a critic.” The idea that to be an effective critic, you have to have no joy in what you’re consuming, is really endemic to pretentious professions. I loved that you gave Johanna a chance to come around on that.

MORAN: It’s just more fun. Why would you ever subscribe to something that is less joyful? There’s something so free about being a fan and being enthusiastic about stuff—you attract all the other people who are also loving and enthusiastic when you’re sending out signals of love. When you start to communicate cynicism and hatred, it leads you down a completely different path. The reason that that bit was so important for me to write in the book was because in the ’90s, it was very rare for a 16-year-old girl to be communicating with the world and print her stuff and have people read it. Now, of course, everyone’s on Twitter, everyone’s on Instagram, everyone’s blogging; any teenager can communicate with the outside world. Having sat on the Internet for 10 years I’ve noticed, time and time again, really young kids just really quickly assuming this attitude of cynicism and like, “Oh my god, fuck you!” When you’re projecting things snarkily, sarcastically, deliriously, and depressively, then people will start responding to you in that way. You’ll suddenly be really shocked, because someday someone will be really snarky and sarcastic towards you about something you’ve done. And you’ll want to be like, “Why am I being attacked? I’m a good person underneath, I was only pretending to be cynical.” But the horrible thing about pretending to be, basically, a cunt, and being a cunt is there is no difference.

SYMONDS: [laughs] Johanna pretends not to like U2, which is a thing everyone does—at what point do you think we stop doing that? Someone says something snarky, witty, and well-timed about something that you, in your heart of hearts, adore, and you put on a…

MORAN: …you throw them under a bus. “Oh God, I fucking hate them too! Please have sex with me.” You always need just one person to start it. I learned this from my husband when I started working at Melody Maker—he was there, too, and he was just this boy in a cardigan and everyone used to pick on him a lot. One night I missed my last train back and he said, “You can come and stay at mine. You can sleep on the sofa, I’ll lend you a toothbrush.” On the way back, he told me, “There’s one thing I need you to know.” I was like, “What’s this going to be, you’re a murderer?”

SYMONDS: [laughs]

MORAN: He was like, “I really love Crowded House.” And I was like, “I really love Crowded House, too!” And that’s how we bonded. He was also the guy at Melody Maker that actually loved ABBA. They’d all be going off to see Skinny Puppy or Front 242, and he’d be like, “No, I’m off to see Björn Again,” the ABBA parody.

He was like the least cool guy ever, but his radiating example of being true to what he loved actually made him a hero and respected by a lot of people who love him. It’s a long game, and it’s not an obvious hero, but if you feel like you can play that role in your social circle, fucking do it. It’s a brilliant thing to do, to not be afraid of ridicule. The whole music thing ties in feminism, as well. You think you’re going to be open to ridicule if you start talking about your periods, masturbation, your abortion, your secret love affair, your eating disorder, or your love of ABBA or of Crowded House. It goes back to what we started talking about, where everyone goes, “Well, that’s not a secret at all. I love that, too!” The big secret is that there doesn’t need to be any secrets. If you tell your secrets, there will always be at least one person who’ll go, “Oh, thank God you said it! We can all be truthful now as well.”

SYMONDS: You’ve been promoting this book for ages, because it was released first overseas. I saw an interview with a guy who opened it by saying, “I loved your book, and I don’t know if it’s just a Gen X thing, or…” And I was like, ” No, dude, I love this book and I’m not remotely Gen X.”

MORAN: [laughs]

SYMONDS: Have you been getting more women telling you, “Yes, this is how women are!” Or people your age telling you, “Yes, this is how it was for people our age!”

MORAN: It’s funny what people pick up on. That’s when you think, “Either I’ve done something that touches on so many aspects of existence that I am a fucking genius, or I really should’ve narrowed down my themes to one or two things.” I randomly wrote a bunch of bollocks, and no one really knows what I am talking about.

In the U.K., the big thing was all about sex, because they’re so uptight and stuff. They were mainly fascinated about the masturbation, in all the interviews we were doing there. When the book launch started reaching the States, it was all about how it was a young adult novel and they thought it was only for teenage girls, which it’s not. Then it went back to feminism, then there’s the rock music thing, and everyone’s kind of going, “Is this what this book’s about? Is this what this book’s about?” It’s about many things, because women are about many things.

The only time I’ve failed to find a specific angle that people wanted to talk about was when it launched in Norway and the interviewer was like, “Do you have any anecdotes of any Norwegian bands you like? Have you ever had sex with a Norwegian man? Do you have any thoughts about Norway? What is feminism like in Norway?”

SYMONDS: [laughs]

MORAN: I was like, “Dude, I can do grunge, I can do sex, I can do feminism, I can do wanking, I can do class. One thing I cannot talk about in relation to this book is Norway. I’m all out there, I’m so sorry.” [laughs]

SYMONDS: [laughs] He gave you so many options!

MORAN: The book could’ve really been called Anything but Norway. It’s got everything in it apart from Norway.

SYMONDS: You mentioned that because of the Internet, teens are much more able to be heard. I wonder whether it’s possible to have Johanna’s story in 2014. I can see it going either way. The idea of a ballsy teenaged girl busting in the Pitchfork offices is totally unfathomable to me.

MORAN: [laughs]

SYMONDS: I can’t imagine that happening. But at the same time, it seems easier to catfish an editor as a teenager in 2014 than it was for you to keep bugging Melody Maker until they paid attention to you.

MORAN: I suppose the key thing now is teenage girls don’t need to go around busting into a male enclave. They don’t have to go to Pitchfork, because they can blog on their own. Tavi does her own fucking thing; she doesn’t have to go knocking on someone else’s door. The only caveat is that generally only girls with well-to-do parents can do that, because after a certain time, bitch gotta pay rent. If you come from a working-class background, you can’t afford to write full time, because you’re just not being paid. Basically, all my arguments come down to Marxist doctrine: The world is shaped by money, so the only voices you’ll hear are the ones with money behind them. But thankfully, culture and cool are some things that circumvent money, because if you’re cool, people will want to give you money—suddenly you shape the market and people start coming to you. Which is why culture—pop music, acting, writing—has always been a traditional way out for working-class people. Sports or pop music, that’s the only way to get out.

People always want something new and exciting, and all these voices we’ve never heard—at some point somebody realizes there’s a huge well of gold there, rather than thinking of paying attention to these people as being a worthy thing: “Let’s give a call to a gay.”

SYMONDS: [laughs]

MORAN: “Let’s give a call to a black lady who has no money. That would be a worthy thing to do.” They’re suddenly like, “No! Shit, they’ve got tons of fucking stuff we’ve never heard of before.” Isn’t it insane we have to send rockets to Mars to find microbes because we’re so excited to find a new kind of life, but a majority of stories and existences we have on this planet never get fucking covered? “I know! Why don’t I stop employing from my circle of straight, white, male friends, go find some diversity, and go find someone else fucking out there who has something to say.” At some point we’ll realize that there’s all that gold buried under those hills. You’re starting to see that now. Since Bridesmaids made a fucking billion at the box office, everyone’s suddenly gone, “Shit! There’s money in dirty, funny ladies.” Ten years ago if you pitched a thing like that, no one would touch you with a barge pole. Now all the money’s going into dirty, funny ladies. It’ll start to happen eventually with every minority voice that isn’t heard, as soon as these cunts realize there’s money in it. When people realize there’s money in the revolution, people are like, “Oh my God! I’m a revolutionary!”

SYMONDS: [laughs] “I’ve been a Marxist this whole time!”

MORAN: “Yeah, all this time, I was extremely interested in your lucrative—I mean, incredibly important point!”

SYMONDS: Your book literalizes something that happens to most teenagers metaphorically: this incredibly sudden, scary, but very exciting, total bifurcation in your personality that happens when you’re 14 or 15. You realize there’s the person you are at home, this role in your family that you’re never going to get away from; and there’s a self that you present to the world; and you’re allowed to have those two things be different. For most people I think it’s not as dramatic as having a literal second name and double life, but I think that most teenagers really do feel that way. I would think that your kids wouldn’t need to do that quite so much, but do you have a sense of who they are outside your house?

MORAN: They’re fucking brilliant, my kids. I am quite a strict mother—the amount of broccoli those children have eaten! They have impeccable table manners. It’s just been amazing watching them turn into people. My parents had eight kids, so they didn’t have the luxury of being able to spoon-feed me through my adolescence or pay me any fucking attention at all or listen to my needs or wants. [both laugh] But when you have the luxury to spend time around them and indulge in things and encourage them, you realize how brilliant it is watching them construct themselves. They have a very sure sense of who they are. My eldest daughter goes to a school where the kids dress really scruffy—like a hippy, progressive, liberal school—so they wear Converse trainers, ripped jeans. The girls don’t wear any make-up, kind of scraggly, long hair. They climb up trees. When she went there, she went through a phase of really liking very pretty dresses—vintage, very 1950s, straw hat, and she’d take everything to school in a basket and stuff. She came back the first day and siad, “To fit in, I’m going to have to dress like these girls for the first term, but after Christmas I’m going to go back to being me.” And then after the first term, when she turned up in this stuff, it caused a sensation. She had the balls to do it—at 11, I could never have done that. Within three weeks, there were four or five other girls who started wearing dresses and bringing baskets; they’re almost like this little cult at school.

SYMONDS: She must’ve made you so proud.

MORAN: Yeah, God, so proud! She didn’t make a fuss about it at all, she just very quietly went, “For the first month I’m just going to keep my head down, and then be me.”

SYMONDS: It’s funny how the context of a school is like a little petri dish—shifts like that happen in the real world, but in larger, much more subtle ways. To actually just be a different person the next day—that’s amazing.

MORAN: One of the key things that I did teach them at a really early age is whenever you say, “That’s not what people do,” you always have to put “yet” at the end of the sentence. All the way through history, everything we think is normal now is something someone would’ve said 10, 15, or even 100 years ago, “That’s not what we do.” That’s just not what they did yet. Every gay man my age, when they saw David Bowie on Top of the Pops, went, “It’s okay for me to be gay.” When I was a girl, the worst thing you could say to a boy at school was “You gaylord, you bender!” And then one of my good friends, Russell T. Davies, took over Dr. Who, which is a children’s show for the BBC, came up with this brilliant character Captain Jack Harkness who’s this bisexual superhero, got him to kiss the Doctor on a children’s show, on primetime TV, and on Monday morning at my kids’ school, the boys were fighting over who would play Jack Harkness in the playground. I absolutely see the correlation between that in 2005 and finally getting the Equal Marriage Act passed in 2012. Russell, working-class, gay boy, writes that show and it ends up affecting legislation in Parliament. You can sit down one day and write something that changes the world, and that’s an amazing thing to know—especially when you’re a teenager and you so badly want to change the world, but you think you have to wait 20 years before you can.

SYMONDS: It’s easy to get discouraged on the Internet, as a progressive who wants to believe people are good, when there’s all this constant evidence about how far we have left to go. What I try to remember is for the most part, we tend not to go backwards. It takes way longer than it should, and the waiting is infuriating, the struggle is difficult, but you know we’re not going to go back to segregation, to a time when women couldn’t vote. We only go forwards.

MORAN: It’s amazing how quickly these things happen. If you think about how long it took universal suffrage, for working people to have the vote instead of just aristocrats and moneyed people, was so long. Then increasingly quickly women got the vote in equality, then the civil rights movement, then the gay rights movement. In the last year it seems the transgender cause has gone from no one talking about it except for making comments about fucking “she-males” and “shims,” to [Laverne Cox] on the cover of Time Magazine. People weren’t really aware of this issue, to be able to debate about this informedly and correctly, and now legislation’s being pushed through in several countries already that you don’t have to state what sex you are in your passport. In several countries, you can change your birth certificate and declare what gender you are and become autonomous, rather than being down to what someone decided for you when you were born. And that’s happened so quickly. I could never remember a wave of enlightenment over a marginal issue like that happening so quickly, with no bloodshed, no marches, just people talking. A couple of really glamorous fucking photo shoots, a shitload of blogs, and a brilliant TV show. This has been the coolest revolution ever. If you think of how long universal suffrage took, it took hundreds of thousands of years of people repeatedly being murdered. [laughs] So many people got murdered! No one murdered in this revolution. It was fucking awesome!

SYMONDS: I think there’s much more ally culture now—it’s hip to be aware of the oppression of people other than just yourself.

MORAN: Yeah! The reason is because it happened culturally. If it just had happened in academia, people publishing some things, and it just being discussed on late-night news shows, and people trying to put forward some legislation in parliament, it would still be seen as a minority issue. Instead it happened culturally. It happened because of TV shows, because of pop stars, and because of people talking. Culture is so much faster and so much more effective than anything else. If you go on a march, you march for a couple hours and it might be on the news that night, but if it happens culturally, it happens forever. Everywhere in the world, that TV show is being played. Someone is downloading it illegally. It’s blowing someone else’s mind. Culture marches so quickly, so inclusively, and it’s a language we all understand. The amount of people who would read an academic paper about trans equality is about six, but the amount of people who’ll watch a TV show and go, “This is really brilliant, funny, sexy, cool”—well, that’s everybody.

SYMONDS: [laughs]

MORAN: That’s why being an enthusiast is such an important thing. When the whole idea about being a critic is that you’re going in there to pick out all the faults with it, then you’re not just criticizing a program, you’re making people more scared to take a risk. No one ever sat down to write a shit TV show. No one ever sat down to write a shit book. People are usually doing shit from the heart.

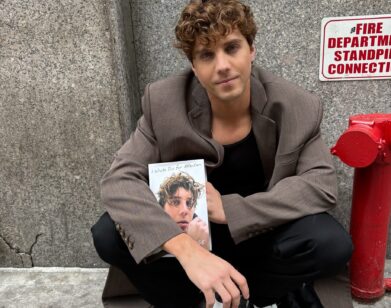

HOW TO BUILD A GIRL IS OUT NOW.