music for reading

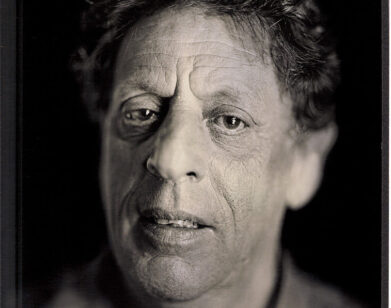

Brian DeGraw on the Lasting Impact of Brian Eno’s Diary

Brian Degraw.

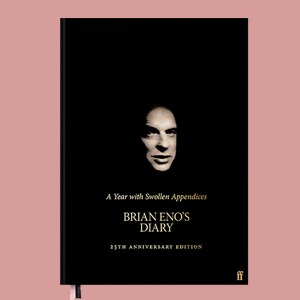

In December 1994, the musician, producer, and all-around artistic renegade Brian Eno came up with a few New Year’s resolutions. While some didn’t last the duration of January—he planned to go to more movies, plays, art galleries—he did follow through on one: keeping a diary. The result was a comprehensive collection of entries on Eno’s work with musicians like David Bowie, James Blake, and Grace Jones, as well as reflections of the artist’s role in a changing world. Filled with razor-sharp wit and poetic insight, Eno’s diary, which he published in 1996 as A Year with Swollen Appendices, became a favorite read of musicians, thinkers, and listeners of all stripes. 25 years later, Faber is publishing a new hardcover edition of the diary, complete with pink paper for the “swollen appendices.” In honor of its 25th anniversary, the musician Brian DeGraw of Gang Gang Dance reflected on what it’s like to peer into the mind of Eno.

I bought a copy of the original edition of this book not long after its was published in 1996. Many of the books I acquired around this time would get read repeatedly and ferociously, until the covers would loosen and fall away, leaving wobbly diagonal piles of pages bound only by the unsightly dried glue of their naked spine. Others rested in neat stacks against my wall, perfectly intact, unread, and covered in dust. A Year with Swollen Appendices was one of the latter. At the time, I was 22-years-old and enthusiastic about the Brian Eno of Here Come the Warm Jets. He of the feathery stage looks and blue eye makeup, the lipstick and berets, the iconic receding blonde-maned gender-bent figure controlling analog synths atop platform heels. Looking back, it makes me wonder if perhaps it was the plain black and white photo of the 46-year-old normie version of him on the cover of A Year that made me, in all of my youthful senselessness, doubt the fact that its contents might inspire. Now, at age 46 myself and a whole lot less judgmental, I’ve finally gotten around to reading this exquisite 25th anniversary edition of Eno’s diary. Its pages hypnotized me, not solely due to the relatable age factor between reader and author, but because it is quite simply a captivating document of a brilliant and relentlessly driven mind.

The main body of the book consists of daily diary entries written throughout the duration of 1995. The entries vary in length, detail, and depth and expose a wide gamut of day-to-day thoughts and experiences. There are the expected entries, which chronicle recording sessions, art installations, and design propositions, but we are also given access to the random corners of Eno’s mind—whether through reoccurring mentions of the unamusing comedy of Jay Leno to an ongoing, nearly obsessive mental catalogue of the various shapes of women’s posteriors. More notably, we see a wide-eyed family man completely enamored with his children and wife, Anthea Norman-Taylor, with whom he is remarkably dedicated to the War Child organization, providing relief to child victims of conflict during the period just after the Bosnian War. No matter the subject matter, every entry reads as a deep rumination on humankind in a way that is so distinctly Eno. The second part of the book— presumably the “swollen appendice,” its pages colored a bubbly yet Pepto-conjuring pink—is a selection of essays, short stories, letters, and musings that classically defy categorization as a whole.

Brian Eno.

Included with this edition is a new introduction by the author, as well as a list that he compiled of new words that didn’t exist at the time he wrote the diary. The list is significant in that it is one of the few aspects of the book that reminds us that 25 years have passed since its initial publishing. Eno’s mind is so far ahead of its time on so many different levels and dimensions that the contents feel as if they haven’t aged much at all. If anything, the rest of us might be just catching up. It’s essential reading for anyone—age 46, 26, or 108—interested in learning not only more about the artist, but of the boundless limits of human creation.