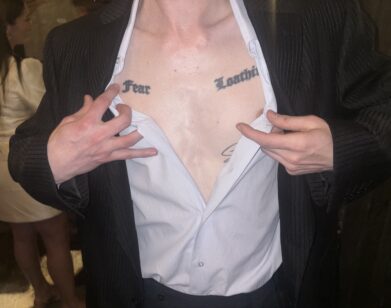

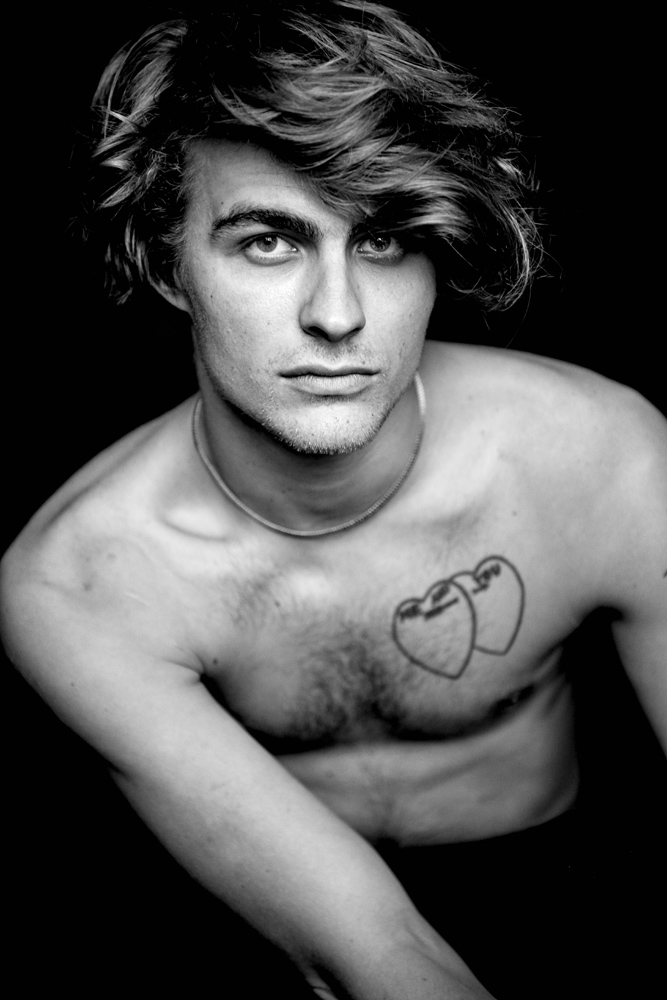

Brett Robinson

BRETT ROBINSON IN NEW YORK, JUNE 2015. JEANS: 7 FOR ALL MANKIND. NECKLACE: EDDIE BORGO. GROOMING PRODUCTS: JOHN MASTERS ORGANICS, INCLUDING DEEP SCALP FOLLICLE TREATMENT & VOLUMIZER. STYLING: KEEGAN SINGH. GROOMING: ELOISE CHEUNG FOR JOHN MASTERS ORGANICS/WSM.

Brett Robinson is in a state of nervous anxiety on an early summer morning on the Lower East Side, bounding around the vacant storefront that will soon house a new café he’s creating for nightclub impresario and graffiti artist André Saraiva. The yet-unnamed eatery and downtown hangout will be the first completed project for the 24-year-old Manhattan Beach, California, native who found his way into the field of interior design largely because he didn’t like skateboarding. “Growing up I would just go to flea markets all the time,” he says. “That’s all I spent my money on.”

Vintage furniture seems an unlikely hobby for a self-described adolescent “punk,” one who claims (improbably, given his charisma and dabbles-in-modeling profile) never to have kissed a girl until he left for college in San Francisco. And yet less than a year after giving up an office job with Ralph Lauren, Robinson has managed to turn his taste for mid-century modernism into a burgeoning career. And how did it happen? “Relationships have been really important to me,” he explains. “Living in New York, you meet so many interesting people; every day you meet someone awesome.” Besides Saraiva, Robinson’s circle of acquaintances includes model Dree Hemingway, whose Los Angeles house he’s now redesigning, and actress Lauren Cohan, for whom he’s doing the same in New York.

But it’s not just who Robinson knows, but what. And if the café on Forsyth Street, just around the corner from hot spot Happy Ending, is any indication, he’s mining an aesthetic vein that throws together high and low, creating a casual “art space” atmosphere that features simple industrial finishes alongside a series of gorgeous Jean Prouvé wooden benches rescued from a former school in France. Robinson is taking the long view, too, looking beyond interiors to furniture-making and even establishing what he calls “an Eliot Noyes operation, a team of architects and art advisers.” He may still be new at this, but his eye for classic design ought to serve him in good stead, and he definitely knows how to end an interview. “Tastes change,” he says as a final note. “But good design doesn’t.”