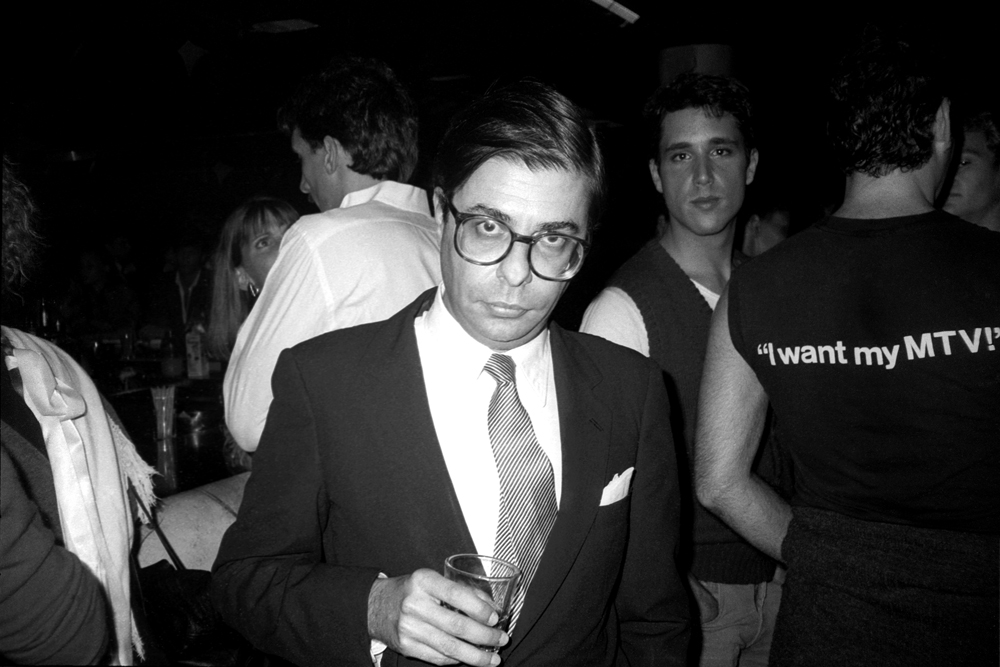

Bob Colacello

We weren’t willfully self- destructive—we just wanted to stay up as late as we could, dancing, drinking, smoking, snorting, and a couple of other thingsBob Colacello

I may be biased, but Bob Colacello’s Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up ranks high among the best books on 20th-century New York society. It’s a delirious thrill ride of Colacello’s 12 years working alongside Andy Warhol at Interview magazine in the ’70s and early ’80s, a roller coaster of art and parties and hit-and-run magazine deadlines and intimate Upper East Side dining rooms and debauched dance floors populated with celebrities, designers, bohemians, drag queens, restless children of dubious world leaders, handsome clingers-on, and scam artists. And like riding a roller coaster, the response to reading Holy Terror is a mix of laughter and screaming, joy and horror—and there is no stopping until the end. The book is a Janus biography: one of Warhol day-to-day, in his later, money-minded, portrait-painter years, expanding his shaky empire through the cultural stratosphere; the other of a young literary man from Long Island thrown willingly to the gorgeous lions of the Manhattan jet set. Holy Terror was originally published in 1990, three years after Warhol’s death, and it is finally receiving its much deserved second life with a brand-new republication this month by Vintage Books. Colacello, now 66, offered a few reminiscences about his insider view of a world and a man so often thought of as existing only as a surface.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You started working at Interview almost by chance and ended up becoming the editor of the magazine for more than a decade. Was there something about the magazine—or that specific time and place of magazines in culture—that was so vital and alive?

BOB COLACELLO: Interview was the perfect title and concept for the 1970s, a time of great social mobility following the cultural and sexual revolutions of the previous decade. Everything seemed so new and fresh and open, and Interview could go with the flow, as we had no obligatory content, only the Q&A format to fill in as we wished. So we interviewed directors, designers, political figures, rock stars, actors, artists, writers, American socialites, titled Europeans, Latin playboys, you name it.

BOLLEN: Holy Terror is packed with stories of working on the magazine with Andy and the team. Is there one interview story that stands out as aere perennius in your mind?

COLACELLO: Going to the White House with Bianca Jagger in 1975 to interview Jack Ford, the hunky 23-year-old son of Gerald and Betty Ford, was a trip. Somehow we ended up doing the pictures in the Lincoln Bedroom, with Bianca wearing a Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo rhinestone-studded black Lycra cocktail dress. I don’t remember whose idea it was for her to climb into the Lincoln Bed—it sort of just happened naturally.

BOLLEN: There was clearly a work hard, play hard approach to your days and nights at Interview. You were burning the candle at both ends. Was it tough to find a sense of balance working at a magazine that encompassed so many competitive social worlds?

COLACELLO: Yes, we were burning the candle at both ends, and even in the middle. But we weren’t willfully self destructive—we just wanted to stay up as late as we could, dancing, drinking, smoking, snorting, and a couple of other things. Balance wasn’t a popular word in the ’70s. Inclusive was not a word you heard much either. Exclusive was. Elite was too. But it was a new kind of exclusivity and elitism, based less on genealogy and wealth, and more on glamour and style. This was the moment when fashion designers became the social equals of the rich women they dressed—maybe even their superiors. Yves, Halston, Oscar, Bill Blass, and Valentino lived and entertained as extravagantly any Rockefeller, Rothschild, or Agnelli. Diana Vreeland was “the Empress,” the avatar of the age. An old name or old money were not enough to get you into Studio 54—or Interview magazine, for that matter. You had to have a lot of something else, like looks or brains or wit or fabulous clothes. Money mattered—when hasn’t it? But it better be cool, because tacky was a popular word back then, too. I know this sounds snobbish, but political correctness hadn’t reared its dreary head yet, putting everyone into victim boxes and banishing discernment, high standards, and fun. We live in the newly named Common Era now, and the land of the lowest common denominator.

BOLLEN: Do you think that spirit and mix in New York is lost? Can editors live so wildly uptown and down and still put out a dynamic monthly?

COLACELLO: I think you have to make the mix—in magazines and in life. Interview does to a degree, as does Vanity Fair. But in my very humble opinion, the former should get uptown a little more, and the latter downtown a lot more. The city is still filled with people who know how to mix things up socially, generationally, sexually, racially, internationally, etc. I’m thinking of Aby Rosen and Samantha Boardman, Diane von Furstenberg, Larry Gagosian, Susan Hess, Vito Schnabel, Deeda Blair, Peter Marino, Dustin Yellin at his Pioneer Works in Red Hook. Part of the problem, though, is people tend to be more private these days. And they will hide even more—if they don’t flee altogether—if our new mayor and city council speaker keep castigating the 1 percent. Envy is a surefire party killer.

BOLLEN: My favorite expression of Andy’s in Holy Terror is when he keeps telling people they should be “kicking up their heels.” What were some of your favorite expressions that Andy used?

COLACELLO: “Falling into a tub of butter” for marrying someone rich; “Bringing home the bacon” for selling art in Europe; “We’re really up there now” upon arriving at Nan Kempner’s or the dinners of other prominent Park Avenue hostesses; and “When will my ship come in?” “It already has, Andy,” was my answer for that one.

BOLLEN: I’ve read a lot of interviews in Interview that Andy has given—often with you by his side—and I’ve always wondered how much of what Andy is saying is actually coming from Bob.

COLACELLO: Pat Hackett transcribed the tapes and would ask me if it was okay to turn some of my questions into Andy’s. And she was a master at extending the boss’s gees, wows, and oh, reallys into complete sentences that somehow did accurately reflect his thoughts. I got good at that too. It’s how we wrote The Philosophy of Andy Warhol with/for Andy, and she wrote Popism: The Warhol Sixties, a brilliant book, and I wrote Andy Warhol’s Exposures. Several photos attributed to Andy in that book were actually taken by me, and I’m grateful to the Andy Warhol Foundation, particularly Sally King-Nero, for sorting out which were whose and returning my prints to me.

BOLLEN: Andy often gets a bad rap as a human being—and in the book he is not always kind to some of his former friends, like Candy Darling. Do you think that came out of fear? Indifference? Or just on to the next new thing?

COLACELLO: What often seemed like meanness or coldness was really fear of emotions and intimacy. And after having three bullets pumped into his gut by Valerie Solanis and nearly dying [in 1968], he had an obsession about never setting foot in a hospital again, which is why he wouldn’t visit Candy when she was dying at Columbus-Mother Cabrini.

BOLLEN: At the end of Holy Terror there is a sense of bad blood between you and Andy—that you were leaving him or because you were writing a book on him. You once mentioned to me that they rushed out [The Andy Warhol] Diaries in an attempt to get ahead of your book. Was it a bad breakup?

COLACELLO: I was 35, and it was time to move on. I was tired of Andy—then in his anorexic Zoli model phase—fed up with the antics and intrigues of his playmates Chris Makos, Victor Hugo, and Jon Gould. Fred [Hughes], who had been a wonderful mentor to me, was jealous of the attention I was getting from Interview‘s success, and sabotaging my portrait commissions with his outrageous behavior at client dinners I’d organize. He would also turn on Andy, once in Paris even trying to hit him, a scene I put in Holy Terror. So, yes, it was a bad breakup, but I slowly reconciled, because there was a deep reservoir of shared experience and affection from working together so closely for so long and so productively. And I never stopped loving Brigid Berlin or Vincent Fremont.

BOLLEN: When you think of Andy Warhol now, where do you picture him?

COLACELLO: He’s commuting between heaven and hell, stopping in purgatory to exchange his halo for horns.

BOLLEN: You are one of New York’s great recorders of places, times, and people. Should we all be keeping accounts of parties we attend? And do you still keep such a detailed account of your life?

COLACELLO: Yes, you should. Everybody should keep a journal or diary. I try to keep mine up. Fortunately, I am blessed with a great memory, inherited from my maternal grandmother. She liked to tell me that the reason she was a Republican was because the party symbol was the elephant, which had a great memory, just as she did. Democrats were jackasses, according to Anna Alberino, of Borough Park, Brooklyn.

BOLLEN: When Holy Terror was originally published, were there any individuals who were unhappy with the way they were presented? I’m thinking of Elsa Peretti and the fit she threw at Halston at Studio 54. Did you fear any Capote-like backlash by the society swans?

COLACELLO: Fran Lebowitz paid me the greatest compliment by saying I told the truth but wasn’t mean to any of our friends. Again I quote Grandma Anna: “It’s not just what you say, it’s also how you say it.” Elsa Peretti didn’t voice any objections, and I think she would have. But then I made it very clear in the book that I was right there in the bathroom, powdering my nose with her and many others.

BOLLEN: When was the last time you saw Andy?

COLACELLO: At Vincent and Shelly Fremont’s Christmas party in 1986. Andy was arriving as I was leaving, and he said, “Gee, why are you going, Bob?” He died two months later, on George Washington’s birthday, and those turned out to be the last words he said to me.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS THE EDITOR AT LARGE OF INTERVIEW MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A FICTION WRITER. HIS SECOND NOVEL, ORIENT, WILL BE RELEASED BY HARPERCOLLINS IN EARLY 2015.