Beyond the haircut: Examining the world of Felicity

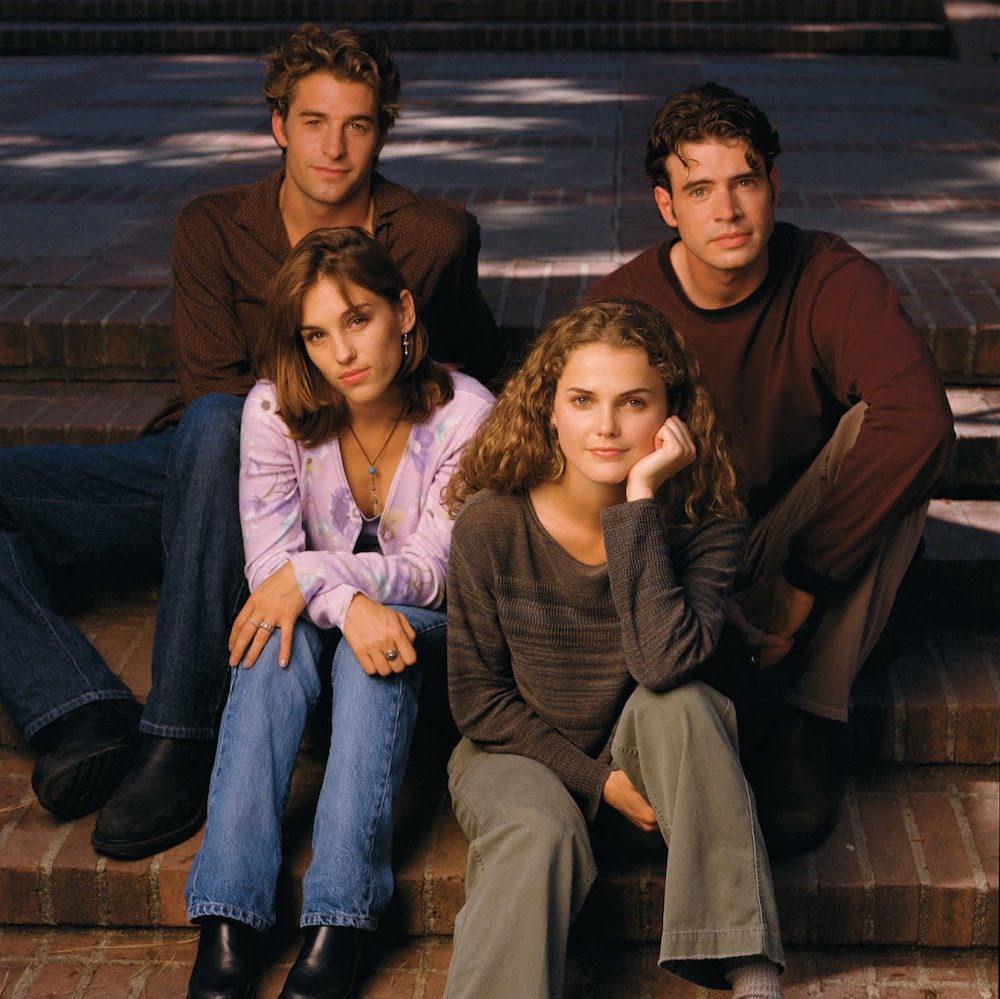

Just 10 minutes into the pilot episode of the criminally underrated series Felicity, I was already considering jumping ship. A slightly delusional high school graduate abandons her plans to attend Stanford and become a doctor to follow her high school crush Ben Covington (Scott Speedman) to New York because of a note he scribbled in her yearbook? My not yet fully developed but emerging feminist self was not impressed with the title character’s decision. But as I continued to watch Felicity Porter, played by a 22-year-old Keri Russell, make mostly questionable life choices, the late ‘90s, early aughts TV drama worked its way into my heart. I first watched all four seasons of the series in 2011 and it is still my favorite show today.

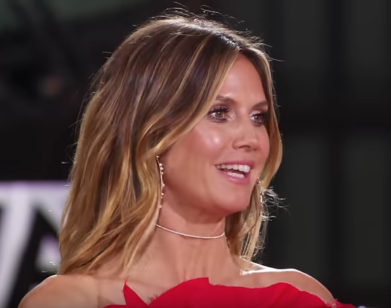

To the outside world, Felicity will probably call to mind one of the following: love triangles; a dramatic haircut in which Felicity chops off her long, beloved ringlet curls into a Ramen noodle mess that was blamed for plummeting season two’s ratings; and college students in New York living in exceptionally massive dorms. But loyal viewers know there’s more to it than that.

When compared to its peers, the lives of Felicity and her friends feel incredibly authentic and relatable. Possibly the rarest quality of all is that in a show about college students, these characters actually attend their classes, go to office hours and even study. In Dawson’s Creek, the characters’ dialogue feels too perfect, never allowing for a “I shouldn’t have said that” moment because every line is so intentional. In Felicity, mumbles and misinterpreted messages aren’t disruptive to the storyline but instead serve as catalysts for character action.

Despite the character’s best attempts at clear communication, the pre-digital nature of the show and the conditions it creates contributes to how the plot unfolds—leaving a note on a dorm room bed or asking an unreliable roommate to relay a message can change the trajectory of an episode. In season one, Felicity runs into her childhood crush, Todd Mulcahy, at a grocery store in Palo Alto, prompting him to fly to New York to see her and see if their connection was still there. Although Felicity is already dating her R.A. Noel Crane (portrayed by Scott Foley), Todd’s visit reignites Felicity’s interest in art, leading her to question her path of medicine. Early in season two, Ben listens to a message on Felicity’s tape recorder intended for her friend Sally in which she confides she might be in love with him. This prompts him to ask to slow things down between them, and eventually leads to Felicity deciding she can’t be with him if she can’t be her emotional self. (And, of course, the haircut.)

Felicity also helped acclaimed showrunner J.J. Abrams to find his signature style—a heady mixture of drama and science fiction. While the SF element is much more prevalent in his other projects such as Fringe and Lost (Felicity was his first television show), it does surface every now and then in Felicity and, on occasion, even informs Abrams’ later works. When Felicity and Julie (Amy Jo Johnson) are in a fight, they happen to find themselves on the same subway car. When the train gets stuck underground, the rest of the passengers become involved in their fight. “Maybe there’s a reason you found yourself on the same train,” a woman on the train offers. “Maybe you two are the reason the train stopped. Well this is why we’re all here. To help you two reunite.” A YouTube user posted a video of this exchange and pointed out that those words eerily predict the plot of Abrams’ successful sci-fi show, Lost.

Further examples of science fiction seeping into this drama are the love spell cast in season one, the Twilight Zone-esque episode from season two, “Help for the Lovelorn,” and the last five episodes of the series in which Felicity travels back in time to see what would have happened if she had chosen Noel instead of Ben. The intended series finale wraps up every storyline in a way that comes full circle, but the WB ordered an additional five episodes which left room for J.J. Abrams and co-creator Matt Reeves to answer both sides of the ultimate Felicity question: Ben or Noel? In every instance of blurring the lines of reality and fantasy, he uses Felicity’s Wiccan roommate Meghan Rotundi (Amanda Foreman) as a device to do so. By grounding these actions in a character, even in the most bizarre circumstances, decisions seem to carry weight and the actions the characters take seem important.

And maybe that’s the beauty of Felicity as a whole. We like to believe that the choices we make matter and that it’s possible to write our own stories and that we won’t be bound to what our parents want for us or what we may feel like we’re destined to do. (My mom was a magazine editor, and, well, here I am.) Felicity plays with the idea that you can change the path you take to arrive at a certain place, but you can’t escape who you really are. When in season three the ever-reliable Noel decides he wants to “let the good times roll,” he highlights his hair and marries a woman he barely knows. But within a few episodes he resumes the role of the geeky, level-headed friend. In “The Graduate,” the final episode pre-time travel, Felicity reveals that she has decided to pursue medicine at Stanford after all, but rather than do it the way she was expected to she moves across the country, discovers her inner artist, and meets her best friends.

So if you’ve never seen the show and you’re longing for the days of floppy disks and cassette tapes, maybe now is the time to binge some Felicity. As our curly-haired friend says in the pilot, “Sometimes it’s the smallest decisions that can change your life forever.”