Beyond Bling

Provenance is something very important in jewelry. You want to know who has worn a piece of jewelry and who it has belonged to-it’s part of its history, part of its aura. Simon de Pury

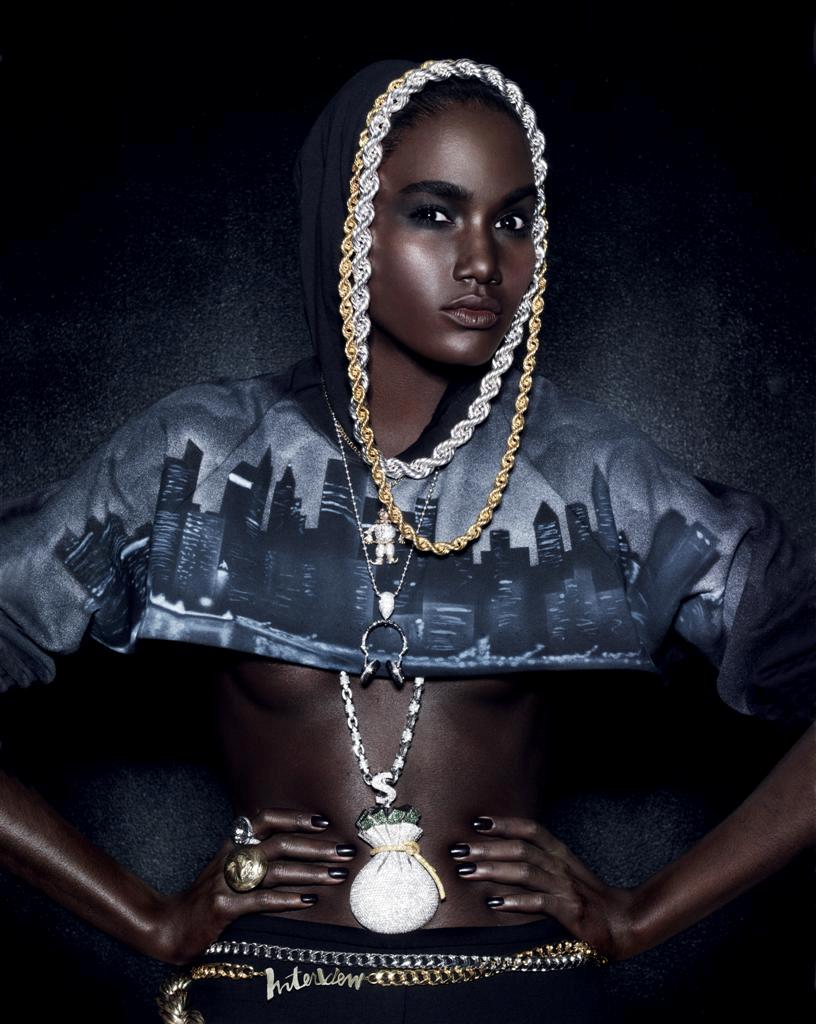

Back in the ’80s when hip-hop started getting hot, the must-have jewelry included phat rope chains, bamboo earrings (at least two pairs, according to LL Cool J), and 14-karat-gold medallions. When hip-hop moved out of the park and into the boardroom in the ghetto fabulous ’90s, the aesthetic received a red-carpet upgrade. We saw the emergence of diamonds everywhere: on necklaces, pinky rings, 10-carat stud earrings-and that was just for the men! Real hip-hop fans stopped saying bling when Katie Couric started using it, but Liberace had nothing on Diddy.

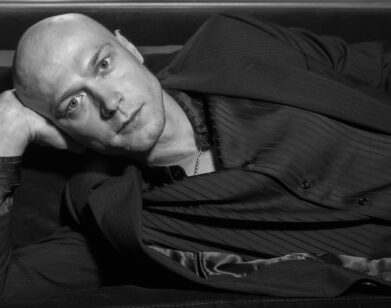

Hip-hop stars are 21st-century royalty, and their jewels from the ’80s to the present will take center stage at one of the world’s most acclaimed auction houses, Phillips de Pury & Company, in New York City. In keeping with its reputation as the young collectors’ auction house, Phillips de Pury will present “Hip-Hop’s Crown Jewels.” The auction is the brainchild of the house’s chairman, Simon de Pury, or as he’s known in some circles, MC de Pury. Don’t let the Swiss accent fool you—de Pury is a true hip-hop fan.

With de Pury’s goal of making sure hip-hop is seen as an authentic art form, 50 to 60 iconic pieces are set to be auctioned off. The proceeds from the sale of five pieces will directly benefit the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History’s Hip-Hop Won’t Stop initiative to build a permanent hip-hop collection. Additional proceeds will benefit Rush Community Affairs, Russell Simmons’s umbrella of nonprofit organizations. Buyers will also have the opportunity to donate their purchases to the museum for inclusion in its hip-hop archives. (Although who could resist at least wearing a piece around the block a few times first?). One thing’s certain: Hip-hop has always got heart.

BEVY SMITH: What’s your favorite hip-hop song and why?

SIMON DE PURY: There are quite a few, in fact. It’s difficult to point out just one. But if I look at early rap, there’s a song called “Genius Rap” by Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde which I absolutely love because of the hook line. It’s completely timeless. I also love “White Lines” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. In terms of more recent hip-hop music, I love Kanye West. If I had to single out one song of his, it would be “Slow Jamz,” which he sings together with Twista and Jamie Foxx. The minute you hear it, you feel in a very special mood. And then there’s Jay-Z—I like most of what he does. There’s one song that I also love by Slim Thug called “This Is My Life.”

BS: You are so buggish gangsta right now with a Slim Thug choice—that is so insane. Houston rap is not really on the national forefront like that. Obviously, you really do love hip-hop. Who would you say is your favorite artist?

SD: Snoop Dogg. I love him both musically and as a personality. What I also admire about Snoop Dogg is his longevity. I mean, he’s been around for a long time and I think he’s as good as he’s ever been.

BS: He also has such a regal bearing about himself. Even though he’s widely known to be a connoisseur of weed and a lover of what some people might say are degrading images of women, he still manages to be a family man-and has a loving spirit about himself. But what I want to know is how did you, a man over the age of 40 from Switzerland, first become aware of hip-hop?

SD: Over 40? That’s very flattering! I’m three years away from 60. But I fell into hip-hop right from the beginning. I was a teenager in the ’60s, so I was putting all my pocket money into buying LPs. I followed the ascent of the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, and Stevie Wonder. I followed popular music very closely, and I’ve never stopped. In the early ’80s, I was blown away when I began to hear some of the earliest hip-hop songs, and I’m fascinated by all the permutations the genre has gone through. I think it’s so vital and vibrant—and it’s here to stay. I felt right from the beginning that it was very, very important.

BS: In terms of your work at Phillips de Pury, I was impressed by your approach to collecting. Unlike most art insiders, it seems like you don’t want an auction house to be intimidating. You have a very wide-open, accessible approach. Who do you see as the audience for the auction? Hard-core hip-hop fans? Collectors of pop art? Speculators?

SD: I think we’ll see a lot of different collectors and buyers participating in this sale. This is the first sale of its kind, and the secondary market hasn’t really recognized the major importance of hip-hop jewelry yet. It is a very safe bet to say that all of these pieces will greatly grow in value going forward. I think there is going to be a whole market that develops around this auction, and we’ll start to see hip-hop jewelry regularly in jewelry auctions around the world. Therefore, anybody who gets on the train early can only do well financially in the long run.

BS: Jewelry auctions always seem to be surrounded by drama and scandal, like the Duchess of Windsor’s auction or Ellen Barkin’s auction of her jewelry from her marriage to Ron Perelman. How do you think that this auction will compare to those in terms of hype and gossip?

SD: Provenance is something very important in jewelry. You want to know who has worn a piece of jewelry and who it has belonged to—it’s part of its history, part of its aura. In a way, there’s nothing more intimate than a piece of jewelry. A painting is hung on somebody’s wall. You put a piece of furniture in your home. But jewelry is worn by a person, so there is a fascination with the history of a piece. In a way, the less important the intrinsic value of the stones on a piece, the more important its history and its provenance becomes. In this show, we have amazing provenances. We have pieces worn by all these extraordinary musicians and major figures from the hip-hop world, and it’s the first time that people will have an opportunity to buy works that have belonged to them. This will definitely be a factor that will add to the interest and intrigue of the sales.

BS: You have some pieces in the auction worn by Tupac and Biggie, two of the most iconic hip-hop stars of all time. How did you get those pieces?

SD: The whole credit for having gotten all these pieces for this auction goes to Alia Varsano, who is the head of our contemporary jewelry department. She has been able to get the invaluable help of major figures such as Russell Simmons and Quincy Jones, and they have really opened a lot of doors for her. Obviously, Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. are two major figures who passed away far too early.

BS: They both died very violent deaths, and many people believe it was due to the culture of violence that has developed around hip-hop in the last 20 years. Are you prepared for critics who might accuse you of profiting off their deaths—that these are blood diamonds, in a sense?

SD: I think that this issue is not something limited to the sale or to hip-hop. In general, you have great artists who have died far too early and who have left great cultural impact. If you look at people like Vincent van Gogh or Jean-Michel Basquiat-there’s a long, long list of artists who have died in tragic circumstances, and far, far too early.

Tokyo is of particular interest because some major Japanese artists have a big fascination with hip-hop music. Simon De Pury

BS: But people look at van Gogh or Basquiat, and say, “Well, yes, but these were true artists.” Whereas hip-hop stars are often dismissed as thugs or hooligans. Here in America, we also don’t really like to include hip-hop as a part of the American fabric. For instance, critics are always complaining about the materialism of hip-hop and accusing the artists of living way above their means. But this ostentatious sort of spending isn’t strictly the province of hip-hop. It’s almost like a continuation of the American Dream. What’s your take on the materialism of hip-hop?

SD: I definitely think that it’s part of the American Dream. First of all, I want to make it clear that I consider these hip-hop artists as major artists independent of whatever categories they’re active in, and so, in my view, I put them absolutely on the same level as some of the contemporary artists or painters of the past that I have mentioned. There is this kind of boldness, this freshness that expresses itself not just in their music but also in their jewelry. It does show the aspirations of people who are trying to be successful. It is the American Dream completely.

BS: You can never separate hip-hop from history. Do you think that the rappers of today will be looked upon as pop culture royalty 200 years from now?

SD: I think that they will, definitely, along with some other great figures of popular culture. This jewelry will be testimony to a very important period when these artists began to have an unbelievable, worldwide influence. If you speak to young kids anywhere in the world, hip-hop is the music that they like to listen to more than any other type, so the influence simply cannot be underestimated.

BS: I guess that explains why you’re taking the items on a world tour. So how do you think that the buyer in Dubai will differ from the buyer in New York or the buyer in Tokyo?

SD: There are a lot of common denominators. For instance, Tokyo is of particular interest because some major Japanese artists have a big fascination with hip-hop music. Take, for instance, the fact that the artwork for Kanye West’s last album was done by Takashi Murakami. There is a gentleman living in Tokyo called Nigo who has started a brand with Pharrell Williams called the Billionaire Boys Club, and all those clothes are very much inspired by the hip-hop culture. I think this mutual fascination has created something of its own. That’s what’s so exciting about today’s world, when you have cross-cultural influences that take place.

BS: The way that hip-hop culture has been commercialized often seems to have been done with a kind of raping-and-pillaging mentality-of people taking hip-hop styles, reformatting them, and then selling them back to the African-American community. Do you feel like that’s really playing into the culture-vulture tradition of taking what African-Americans contribute to pop culture, and then taking it mainstream with African-Americans themselves being left out of the equation?

SD: I think that creative people, wherever they are, in any field, take inspiration wherever they can find it. I think it’s a tribute to the artistic importance of hip-hop culture and what hip-hop has brought into music and fashion and jewelry that it is being adapted or imitated or is inspiring variations or new types of art or new types of music. It’s not a negative thing. I think imitation is always the greatest form of flattery.

BS: And art and commerce can go hand-in-hand-“Cash moves everything,” in the words of Wu-Tang Clan.

SD: Well, there has always been a correlation between money and art. This is nothing new.

BS: This is the first time that hip-hop culture will be put on the artistic pedestal alongside other contemporary art. What do you hope to achieve?

SD: At Phillips de Pury we like to be pioneers in what we do. We hope to make jewelry sales much more exciting in general. When I look at contemporary art catalogues or auction catalogues in other categories, I get very excited, but when I look at jewelry auction catalogues, I get quite bored. So I want to bring the excitement that you have in all other collecting areas to jewelry.

BS: The first time I ever really saw hip-hop being represented in art was through Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. But today we have an artist like Kehinde Wiley making art that is not at all abstract. It’s really literal-he’s painting B-boys and thugs and rappers in the style of the old masters. What correlations do you see between hip-hop and contemporary art?

SD: It’s so interesting when you follow art over a certain period of time. I saw a Keith Haring retrospective in Lyon, France, earlier this year. In a way, you see his work with new eyes. When you see that it remains so elegant, so strong after all these years-in fact, even stronger than when you saw it for the first time—then you know it’s going to be there to stay. That is what I feel with the best of hip-hop music and with the best of what has been produced by hip-hop culture. It is going to be timeless, and it’s going to last.

I judge each piece of jewelry on its visual impact and the pleasure of holding it in one’s hand and just looking at it. Simon De Pury

BS: Which is why, I guess, the National Museum of American History is actually building a permanent collection devoted to hip-hop culture. I know that Phillips de Pury is collaborating with them on this auction. How did that come about?

SD: That’s an important aspect. There is a charity component to the sale. The museum is expected to write the forward to the catalogue, and the museum’s Hip-Hop Won’t Stop initiative has the goal of establishing a permanent hip-hop collection. Five pieces in the sale will fully benefit the museum-and anybody else who buys a piece in the sale has the option of donating it, if they wish. I think it’s great to know that hip-hop culture is going to be properly honored on a permanent basis by the Smithsonian. Then there is Russell Simmons, who is not only a legendary figure in the hip-hop world and an amazing businessman, but is probably one of the most generous men around. A portion of the proceeds from the sale will benefit the Rush Community Affairs foundation that he has created.

BS: In the early days of hip-hop, people started out wearing the gold rope chains, the bamboo earrings, name chains, and all that. Then, when the hip-hop artists started making hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of dollars, the jewelry became more sophisticated and ornate. For instance, you guys have the “Money Bag” pendant worn by Lil’ Wayne of Cash Money Records, which is a white-gold piece that’s just dripping in diamonds. You also have a really beautiful diamond bracelet that belonged to Sean “Diddy” Combs. It’s gotten so sophisticated that I wouldn’t be surprised one day to see Kelis wearing a piece worn by the Duchess of Windsor.

SD: It would be perfect for Kelis to wear something from the Duchess of Windsor. You would also have wanted the Duchess of Windsor to wear some hip-hop jewelry. That’s the best thing that could happen.

BS: What’s your favorite piece in the auction?

SD: My favorite piece is probably the Biz Markie necklace with headphones. I spend a lot of time listening to music with my headphones-of course, not diamond-encrusted headphones.

BS: No, not yet.

SD: I think headphones are a beautiful object, in fact, and so to see them as a jewel and hanging on a necklace, I found very appealing. I judge each piece of jewelry on its visual impact and the pleasure of holding it in one’s hand and just looking at it. Sometimes, even if you do not know the context, it’s okay, because the object is there, and it speaks for itself. I really do believe that any of those pieces of jewelry in the sale can be worn by anyone. You don’t have to be a hip-hop artist to wear them. That is the excitement of it. I think that’s the appeal of this jewelry-it is going to go way beyond the hip-hop crowd in the same way that the appeal of hip-hop music has. That is why it’s so important to get it widely known, and for collectors to be able to appreciate it on its own artistic merits and its own innovative quality.

BS: Back in the day, my friends and I would go down to the diamond district in New York City, and we would just look for the most ornate, gaudy stuff. That Rolex that you have in the sale means so much because Biggie wore it at a time when hip-hop was really coming into its own. The money was flowing and everyone had gone from just wanting to be the fabulous, flashy, fly guy on the corner, to actually having aspirations of being a CEO, the Boss—of having an office and a secretary and the whole thing. Another piece you have in the auction, MC Lyte’s Nefertiti ring, is saying, “You know what, you might call me a bitch or a ho, but I’m a queen.” I think this auction is going to mean so much to so many different people. You’re just putting it all in a whole different light.

SD: I hope so.

BS: In the last millennium, I fancied myself a rapper. My name was MC Bevski, and I worked Harlem. If you were a rapper, what would your name be and what place would you represent?

SD: I’d love to be a rapper. My name would be MC de Pury, and I would probably represent Basel, Switzerland, which is my city of birth. One of my other great loves in life, besides art and music, is soccer. Being Swiss and loving soccer is a fairly masochistic experience, because our football teams are not really great on the international scene. So me being MC de Pury and representing Basel is not so great on the hip-hop scene, but still, it’s nice to dream about it.