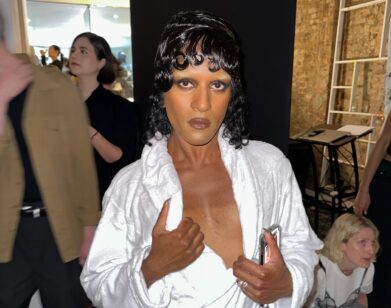

Benjamin Paulin

Growing up immersed in a world of his father’s making, Benjamin Paulin didn’t consider his interior surroundings. “For me, it wasn’t eccentric; it was normal,” says the 37-year-old musician of a home filled with the radical design and décor of Pierre Paulin, one of the most influential designers of the 20th century. Few defined the moment as sharply and seductively as the elder Paulin did the 1960s and early ’70s in France. It was a look largely built upon what Benjamin considers his father’s most important discovery: jersey fabrics stretched over Pirelli foam to create new, sculptural modes of seating. “It was a revolution in design,” says Benjamin. It also proved a technical innovation that birthed a new language of form and function, giving rise to a generation of curvaceous, organic shapes that included Paulin’s iconic chairs for Artifort, such as Mushroom (1959), Orange Slice (1960), Ribbon (1966), and Tongue (1968). The furniture is close to the ground, molds to the body, and tends to invite more casual and personal configurations. Along with his interior work in the late ’60s and the ’70s for the Denon wing of the Louvre, an apartment for President Georges Pompidou at the Élysée Palace, and an office for Christian Dior, Paulin heralded a new way of living that was unrestrained, playful, and rebellious. It reflected the social and cultural upheaval of the era.

“I only realized the importance of my father after his death,” says Benjamin, who is now dedicating his days to preserving the legacy. Together with his wife, Alice Lemoine, and his mother, Maia—Pierre’s business partner since 1972—the family launched Paulin, Paulin, Paulin in 2008, the year before his father died at age 81, to oversee the 50-plus-year archive. Filled with drawings, models, and a trove of unrealized works, the company is partially run out of a house Pierre and Maia built in the mid-’90s in the Cévennes region of southern France.

“My father didn’t consider himself a creator; he considered himself a discoverer,” says Benjamin. “He always told me everything was already there. You don’t create things, you only see them before others do.” Now a selection of “discoveries” from the archive—some that never made it past the prototype stage, others specially commissioned for the Mobilier National, the agency responsible for outfitting French governmental buildings—are being produced for the first time in limited edition for a series of shows at Galerie Perrotin. Among the trove are two spectacular pieces that Benjamin remembers fondly from his childhood—La Dèclive (1966), an articulated lounge chair made of foam and lacquered aluminum that appears to curl up around you à la Beetlejuice; and Tapis-Siège (1970), an unrealized origami-like “carpet” for Herman Miller. The majority of the Paulin works are now on view at Perrotin’s New York gallery, where you are encouraged to sit back and give the furniture a test run.

Add to this the first major retrospective of Pierre Paulin’s work at the Centre Pompidou this summer and the release of Benjamin’s latest pop album, Meilleur Espoir Masculin, and you could say the Paulins are having quite a year. Still, says Benjamin, “we have a lot to do, and there is still a lot to tell.” The archives might very well continue to offer new ideas on design for decades to come.