Barra Grant Is Miss America’s Ugly Daughter

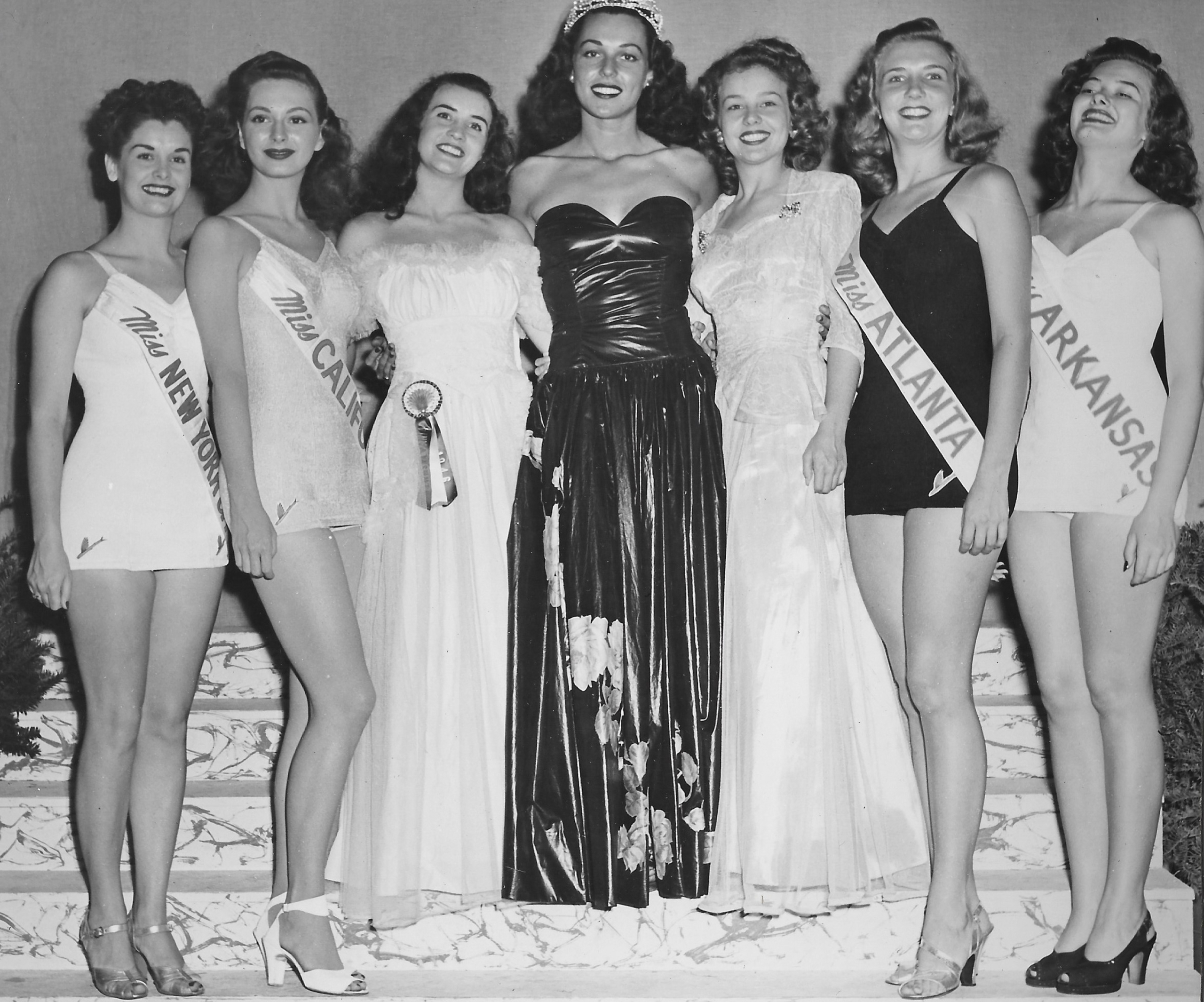

A young Barra Grant.

The story of Bess Myerson is the story of America, or at least some version of it. A poor Jewish girl from the Bronx who was entered into the Miss America beauty pageant without her knowledge on the day of Japan’s surrender during World War II—and against all odds won—Myerson became a hero to the community. As the first and only Jewish Miss America, she was “the most famous pretty girl since Queen Esther,” as Susan Dworkin wrote in her 1987 biography of Myerson. At 5’10 with a pearly smile and quick wit to boot, Myerson was made for television. She soon landed a spot on the long-running hit game show I’ve Got A Secret, before diving headfirst into politics and mingling with the likes of the Kennedys. It wasn’t long before the New York native became the city’s first commissioner of consumer affairs and campaigned heavily for Ed Koch’s run for mayor in 1977, undoubtedly helping him secure the vote. The tabloids ate her up: Myerson’s two ill-fated marriages and several other tumultuous relationships established her in the press as a tortured beauty, culminating in arrests for shoplifting and erratic behavior. When she became romantically entangled with a married sewage contractor doing dirty business in a story the press dubbed the “Bess Mess,” her pristine image became marred with scandal.

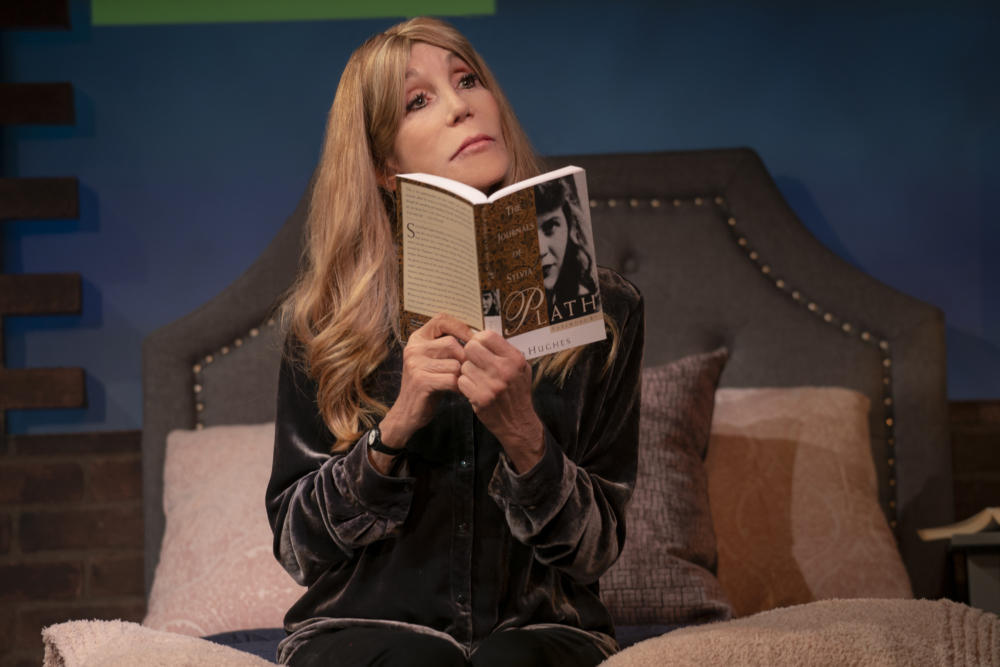

It’s the ugly side of Myerson that is explored in the new Off-Broadway play Miss America’s Ugly Daughter, in performances at the Marjorie S. Deane Little Theater until March 1. A one-woman show written and performed by Myerson’s daughter, Barra Grant, the play is a raw, darkly funny look into the tumultuous inner life of a public figure, from the perspective of her closest confidante. Grant takes the audience through her own journey, from a “bulky,” alienated kid who finds solace in Sylvia Plath to a burgeoning screenwriter and actress in campy ’70s films like Daughters of Satan. Her relationship with her mother is thorny and at times verbally abusive, though the portrait she paints of an aging beauty queen is not without empathy. Throughout, she takes phone calls from her mother, who bemoans the bygone sparkle of life in old age, and attempts to grab hold of it with pills, wine, and an all-carrot diet. Ultimately, the Myerson story, like America’s, is one that begs to be understood, one that champions the ugly duckling within the swan. For Barra Grant, Miss America’s Ugly Daughter is just the surface.

———

SARAH NECHAMKIN: How are you?

BARRA GRANT: I’m good. Opening night is tomorrow. It’s brutal, but it’s terrific. It’s like running a marathon, but it’s worth every minute. It’s just so special for me to be able to do it here in New York. We did it in L.A. a lot, three different theaters, but it’s really a New York show, because she was a New York figure.

NECHAMKIN: And you grew up in New York?

GRANT: I did. I went to high school here, then I went to college, then I moved to London, then I came back here and I wound up in L.A., because I’m a screenwriter and that’s where you have to be. It’s a very New York show.

NECHAMKIN: When you did you decide that this was the story you want to tell?

GRANT: I had been performing a series of stories in L.A., and I realized that all the stories I told had a common theme, even if they were about going to the drug store. The theme was about myself and my mother and my relationship with her. I have a daughter of my own, so it’s kind of figuring out what kind of mother you want to be. And my kinship with my mother was very intense, because there was a long period of time when I was a child where it was just her and me. My father had passed, and we were alone together, and it was a real seminal time in my life. When I started to write these stories, I explored all these different avenues of me and my mother, and I realized that my story was universal, that all girls have issues with their mothers, and they’re trying to sort that out their whole life, trying to decide should they be like their mother or raise their kids maybe in a different way than they were raised. It’s always the dilemma. One of the themes of the show is about acceptance and forgiveness and a kind of understanding about how to move on with your own life.

My mom was a big celebrity, and that colors how I grew up. There’s a very special existence you have when you’re the child of a celebrity. It’s surreal walking into a restaurant or walking down the street and having people stop your mother for her autograph, traveling with her, having everybody know who she was. The reason it’s called Miss America’s Ugly Daughter is that when I was a kid I was very chubby. I had buck teeth. I was kind of shy. And you think of yourself that way your whole life, in a way. Even though you go on a diet, you straighten your teeth, and you become a prettier version of yourself, you’re still caught in a bind of how you were when you were little, and it stays with you your whole life. My mother was obviously gorgeous, and that made it hard.

NECHAMKIN: Was it cathartic for you to write the script?

GRANT: I started writing it a few years ago. When I decided to add the idea that my mother was calling me on the phone throughout the show and speaking to me while I was trying to move on and tell my own story, her interruption really stitched it together. I wrote a lot of the show with a sense of terrific humor, to say those things that might be painful or difficult to deal with can be explored through comedy. A lot of my growing up was comedic, because it was so absurd having this queen as a mother.

NECHAMKIN: There’s a big tradition for that, too, in Jewish-American writing and media. The dark humor.

GRANT: Yeah. It’s really necessary. Pain and confusion are best expressed through humor. Otherwise, it becomes a sob story, which I didn’t want to do.

NECHAMKIN: I know you talked about Sylvia Plath in the show. How much do you find that other works have influenced this play, in particular, or your other writing?

GRANT: I’ve always been a big reader. Books were my go-to place of comfort and inspiration. But when I grew up, I thought everybody was Jewish. I grew up in a Jewish world. My mom, she did a lot of work for Israel Bonds, Anti-Defamation League, B’nai B’rith, all of them. And I often was brought to those dinners to be able to hear her give her speeches. She took me to Israel twice. I met [the Former Prime Minister of Israel David] Ben-Gurion. I saw [Adolf] Eichmann on trial. Israel was very powerful for me.

Barra Grant in Miss America’s Ugly Daughter. Photo by Joan Marcus.

And I liked being Jewish. I loved the history of the people and the fact that so many Jews were at the forefront of different science and literature—everything but athletic feats. I also loved the language. I loved the way Jews worked with the language, their sense of humor, the darkness that overrides a lot of thinking. I’m drawn to the dark side in a comedic way. I think that being middle of the road is not very interesting if you’re a writer. And I think once you find your voice, it’s extremely comforting to know that you have a door, a well that you can draw upon. I just loved the essence of Judaism.

NECHAMKIN: And then you ended up marrying an Irish Catholic.

GRANT: Yeah, I married an Irish Catholic, which didn’t go down so well with my mother, but he was so terrific and such a great guy. He finally made my whole family adore him, and he was a beacon in my life. Before that, I had mostly dated Jewish men. When Brian [Reilly], my husband, came along, it was surprising. If I had a dark place I went to, he was in a place of light. He drew me into a different sensibility where everything stopped being tragic or melancholy, and I saw the brighter side of things through him. It didn’t change me utterly; I remained a dark-sided person, but it was a big relief to have him in my life. I lost him to cancer, which was a big tragedy. But we have a daughter who is part of both of us. It was nice in the end to have two sides to my daughter being raised. She was a real mutt.

NECHAMKIN: Someone told me once that the two types of people that get along best are Jews and Catholics. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s the guilt thing.

GRANT: It’s an interesting combination. And guilt is a big one. It’s a wonderful theme.

NECHAMKIN: You think so?

GRANT: Oh, I think so. I think that all feelings that are difficult, like guilt, depression, and anger are the most interesting feelings to explore. And as I said, if you can come out with a humorous take on it all, it’s a wonderful mental place to be in, because you accept all the difficulties, because you know how to laugh about them and they become less painful and intrusive. You’ve developed survival tactics that are good to have against the tide, against the world at large. It’s good to be a survivor, and it’s good to hold on to your past and see it not with rose-colored glasses, but as a fascinating journey. You survived the bad stuff.

NECHAMKIN: Did you find that there were specific memories that came up as you were writing? Was there anything that surprised you, or did it always exist this way in your head?

GRANT: I knew what I wanted to talk about. I knew what I wanted to inhabit as the character. I think the most surprising thing was how much of it was comedic, and that I shaped it with that intention. When I hit on specific events that in real life might have been really painful, and when I found that I could hear laughter in my head about these events, I automatically knew what to include in the show and what to exclude. It was like being a sculptor and sculpting away at this slab of marble until I found a shape, until I found myself. When my mother calls me, she’s already in her seventies, and she wanted to be comforted about being old and not having a man in her life.

My mother had always been very beautiful. Age was very difficult for her. She never wanted to be old, but beauty queens become old, if they live. Her adjustment to being “an old lady” was difficult, and I had to be there to put plugs in the dam that was breaking and comfort her. Because her past had been so vibrant and inspirational and important that when she was sidelined by old age, life became difficult. There are women who grow old gracefully and who keep working through their older years, and my mom did. She kept giving speeches. She kept alive through Judaism. But it was different than when she was a younger woman.

NECHAMKIN: I was so taken by the specificity of things in the show. There was that carrot line … was that real? And that she called you “bulky?”

GRANT: You have to not exaggerate, but you have to rephrase stuff. My mother often was on a diet. Whether it was a carrot diet or a spinach diet, the line about it being a carrot diet worked: “I’ve had so many carrots I can almost see in the dark.” It’s a funny way to say it. I don’t know that she called me bulky, but she was interested in what I looked like. I was, as a lot of children are, chubby and chubby too long. I finally became tall, and when I became tall, I became thinner and I looked more like my mother. If you see pictures of us together at a certain time, I never looked like a beauty queen, but I looked better than I did when I was nine. I think beauty queens do put an emphasis on what their children look like, but at the same time, my mother was a rabid intellectual. She was extremely smart, and my intellect was very important to her, that I studied, that I learned. My mom was also a concert pianist. She played Grieg on the piano and Gershwin on the flute for the pageant. She made me take piano lessons, but I never hit the mark. I was never very good. My mom had a lot of discipline in terms of her own education and her own mastery of language, communication. She spoke out against anti-Semitism from a very early period of time. She was only 21.

NECHAMKIN: She bore the brunt of a lot of anti-Semitism too, because it was right at the end of World War II that she won the pageant.

GRANT: Right. And America blamed the Jews for the war. When she went out on her tour, people didn’t want her. Catalina didn’t want her to wear their bathing suits. General Foods didn’t want her commercials eating their food. And Miss Americas earned money by doing these appearances. My mom wanted badly to buy her own piano, and, unfortunately, she had to quit halfway through her tour, because no one wanted her in middle America. The Anti-Defamation League then scooped her up and had her go back into the country of America and give this speech called “You Can’t Be Beautiful and Hate.” And she gave it to kids in high school who still had the ability to not become their dads.

When she won Miss America, it was beyond anybody’s dreams that this Jewish girl with wild black hair and a skinny body—compared to the other contestants, who were blonde and cherubic and plump, who did things like yodel—no one expected her to win. One of the judges got a note slipped under her door, “If you vote for the Jew, you’ll never come back to the pageant to be a judge.” They gave her a terrible green bathing suit, while all the other contestants were in white suits. And the suit was too small. Her sister slept in it overnight, cause her sister was heavy and finally made it fit. And she was the only contestant whose mother wasn’t there, because her mother was illiterate and not like the other mothers. So her sister went with her to the pageant. She’s the only Jewish Miss America that ever was, largely because Jewish girls don’t enter beauty pageants. And she only did it because she wanted to get a scholarship to Juilliard.

NECHAMKIN: Do you feel like there’s a certain responsibility you have to communicate all of the good things that she did? Because obviously there was the whole scandal, and you talk about it, but you don’t really go into too much detail. Is there a feeling that most people don’t know about the many good things that she had done with her life as much as they know about the scandalous?

GRANT: Yeah. The scandal was really a horrible experience, the mistake she made by becoming involved with that Andy Capasso, the man who brought her down. Obviously, it’s part of the show, because all those phone calls are from a woman who’s very isolated, and the scandal did isolate her from a world she lived in. There was so much more good than bad, but I would have been lax if I hadn’t included the scandal. It’s interesting to be someone who’s at the pinnacle of cultural life and importance in New York City to have had to endure what happened. I think people whose lives have been scarred by tragedy or a fall from grace are fascinating and complex people. We all hit walls in our lives, and we all have to pick ourselves up and begin again. And that’s what my mother did. She survived it, and she continued to speak out against bigotry and hatred. She was a survivor.