Avedon Exposed

By the time American culture was undergoing cataclysmic changes in the late 1960s—changes that permanently altered not only how the country saw itself in the world, but how each individual saw him- or herself in society—Richard Avedon was already a legend. He had established himself as one of the key national chroniclers of his time. But as a rollicking new exhibition of the late photographer’s work opening this month at Gagosian Gallery in New York City reveals, Avedon didn’t just tackle this brave, new state of America he found swirling outside his studio at 110 East 58th Street—he radically modified his own style, approach, subject matter, and even scale to document the massive social forces pressing in from all sides. Gagosian’s “Richard Avedon: Murals & Portraits,” presented in collaboration with the Richard Avedon Foundation, inventories the various cultural heavyweights and personalities Avedon documented who were redefining the morals, values, and politics of the United States in the ’60s and ’70s. Among the dignitaries photographed in Avedon’s direct, unblinking, black-and-white style, pressed almost like a cultural specimen against a white background, are the Chicago Seven, the United States Mission Council, American soldiers, Vietnamese survivors of napalm attacks, Andy Warhol and his notorious Factory, transgressive writers such as Allen Ginsberg and Jean Genet, and members of extremist groups such as the Young Lords and the Weathermen.

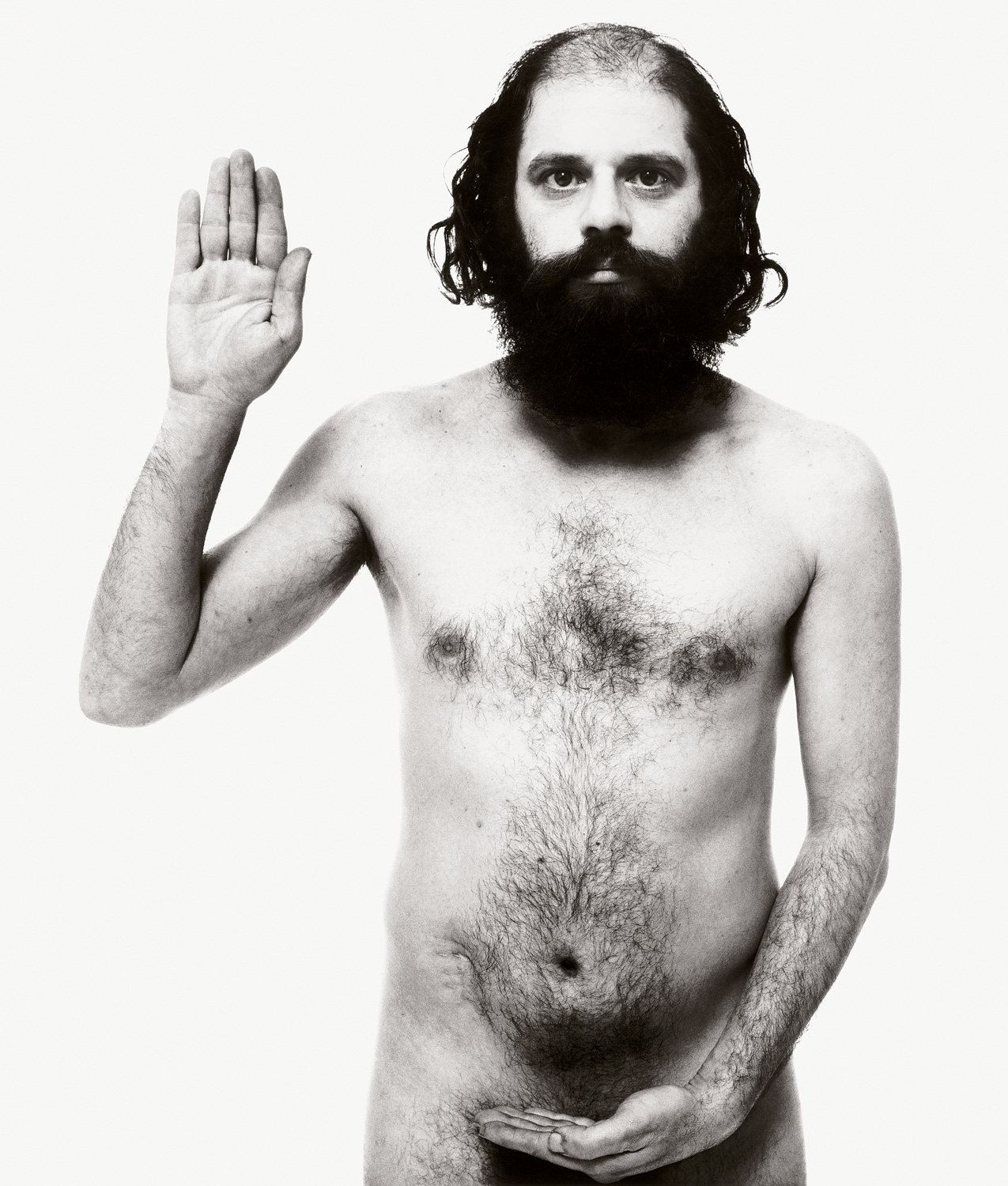

Certainly Avedon was not afraid to let his photographic odyssey become overtly political, but along with the power players, he especially enjoyed making portraits of radicals. That meant a transition in not only who he photographed, but how he photographed—and one of Avedon’s signature visual tropes during this period became nudity. According to critic Paul Roth, former executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation, much of this interest in subjects stripping down began in 1969, photographing the members of Warhol’s Factory, who tended to be very comfortable with taking their clothes off. But, of course, even earlier, Avedon was getting people at their most elemental and exposed, as evidenced by the early 1963 photographs of Allen Ginsberg. Perhaps Avedon had intuited a message found in Ginsberg’s 1956 poem, “America,” in which Ginsberg asks: “America, when will you be angelic? When will you take off your clothes?” No matter the message, Avedon had many wondrous subjects reveal themselves in front of the white backdrop of his busy midtown studio. On the occasion of the Gagosian show, we spoke to a few of the sitters (or standers) of that era, who recollected their memories of posing for Avedon, and we asked Roth to spell out exactly why the nude was such a riveting, revolutionary approach to photography—and why it remains so very much Avedon’s iconic domain.

TERRY GILLIAM, Monty Python member

When we were in New York in 1975, I was already a big Avedon fan. We got asked to come and be photographed by him—we were hot stuff then—and I tried to warn the others ahead of time. It was the period Avedon was photographing celebrities with their clothes off in one form or another. We all agreed that we weren’t going to take our clothes off at the shoot, that we weren’t going to fall for that just because everyone else was doing it. Definitely no. But when we arrived at the studio, Terry Jones immediately said, “You want us to take our clothes off?” And Avedon said, “Yes.” We said, “What? Shut the fuck up, Terry!” [laughs] Avedon was a very sweet man, very nice and quiet and unassuming, and before we knew it, he somehow got us to take our clothes off. We did manage to say, “We’re going to keep our hats, socks, and shoes on.” That was the deal. We had to maintain some dignity. My wife says she actually chose me out of the crowd because she liked my bum! The whole experience was very strange because you are standing there trying to cover your balls in the middle of this large black studio with assistants, who you can’t quite see, running around in the dark and soothing music is being played in the background. Avedon pushed us into the middle of the space, and we just started assuming poses we could live with later. Not only did Terry take his clothes off, but he had to dangle everything upside down. He liked flaunting his body in those days. The rest of us were sort of like trapped animals in the headlights, and Avedon was somewhere in the shadows clicking away.

VIVA, actress, Warhol Factory member

I did a lot of shoots with Avedon. I did one with the Warhol Factory, and then I did a whole series with my husband, Michel [Auder], and one where I was pregnant and I was squeezing milk out of my tit. I kind of got sick of doing them, but Avedon kept calling. I’d say, “Oh, I’m just too tired.” And he’d say, “I’ll send over a limousine to get you.” And I’d say, “Well, grab me some caviar and champagne, too.” So every time I went over there—which was at least four or five times—he would know to have a limo, champagne, and caviar in a white porcelain jar. He was very warm and sweet to me. He gave me a whole bunch of photographs of Michel and I, but we had a fight and Michel ripped them up. Then I saw Avedon later in Malibu, one night at a dinner at Joan Didion’s, and he made a deal with us that he would reprint the photographs for us if Michel and I stayed married for 10 years. Which, of course, we didn’t.

JUDITH MALINA, co-founder of The Living Theater

We were very “in” that season. We were running all over the place and were invited by Avedon to come and be photographed. We were delighted, of course. We got there and took our clothes off. But I remember we also got him very high. We brought some weed and he got high with us. He was so high, and he said, “These must be the most beautiful photographs I’ve ever taken.” That’s what he said then. I don’t know if he thought that later! But after we got naked, we just sort of moved around freely, having fun, and he photographed us. This is me, with my back to the camera. That’s my tush. I’m not shy. It just happened that way.

JAY JOHNSON, Warhol Factory member

I ended up doing three different shoots with Avedon. Initially, everyone that Andy invited went to the studio, and Avedon took a group shot of us. But I guess he didn’t really like the way it looked and decided to shoot it again, selecting who he wanted himself. Then he decided to break us up into groups. For the third shoot, it was just three of us—me, Eric Emerson, and Tom Hompertz—in that little nude section. Avedon did the sections individually, and I remember him explaining how he was going to organize and put them together. I was about 19, and I had heard of Avedon, but I had no idea I was going to end up doing a nude photograph. I don’t think I had ever done one before. I look at photographs of people today, and I think, My God, look at these amazing bodies. But at the time, I thought I was skinny and unattractive. I didn’t understand why anyone would even want to photograph me. But I’ve been told that Avedon had in mind “the three muses” for our section. The way the photograph actually happened was that we started dressed, and Avedon started saying, “Take off your shoes, your shirts . . .” and eventually we were nude. The nudity was premeditated, but I wasn’t aware of what was happening. [laughs] Avedon was impersonal. He had his idea of what he wanted to do, and he was very clear about it. I think the first time I saw the final photograph was when it was at the Whitney for Avedon’s retrospective in 1994. I was a little surprised when I walked into the room and there I was, about 20 feet tall.

JOE DALLESANDRO, actor, Warhol Factory member

It was a long time ago. All I remember is Paul Morrissey being there and directing what he wanted us to do along with Richard telling us what he wanted. It was very much “get it done.” That was my attitude back then. “Hurry up, get it done.” I always felt kind of uncomfortable with the nudity, but I did it if it was called for. Avedon was already famous by then. But to me, it was just another important photographer. We’ve been shot by many of them.

PAUL ROTH, senior curator and director of photography and media arts, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Avedon would often say that, in those days, you couldn’t keep the clothes on the people—you couldn’t keep them from stripping down to the nude. It always got a laugh, but I think there is some kernel of truth to what he said. In this period, Avedon was really fascinated by youth culture, and the culture was being overrun by a rebellious spirit. For years after the Eisenhower era, any expression of personal freedom was valued by some and loathed by others. Diana Vreeland, who Avedon was very close to, came up with the term youthquake, and Avedon, starting in the early ’60s, was caught up with that. By the late ’60s Avedon became quite radical and started changing his style, both in response to his own desire to be an artist and also in response to the transgressive energies that were going on in culture. He wanted to capture the circumstances or physical manifestations of that shift. So nudity became a part of his portraiture. He didn’t do it a lot. If you go through his entire body of work, you won’t actually find an egregious amount of nudity. But nudity is an innate symbol. It immediately suggested that something radical was happening, that the people he was capturing lived outside of the norms, that they didn’t wear uniforms. And he only captured subjects in the nude who were known for that sort of thing, The Living Theater or Warhol’s Factory. The Warhol Factory, for example, functioned at odds with the larger culture, and the sexuality and gender shifting of the Factory was part of that. So nudity was a way for Avedon to get at these issues visually.

In 1969, the tools Avedon used were the same tools he had used before. He photographed with a big 8 x10 view camera, which was already kind of anachronistic at that time. It’s the kind of camera we associated more with Nadar in the 19th century. He photographed people against a white backdrop so that there was no contextualizing, no environment for us to locate or place them. He had done that before, but in 1969, he made it into a fetish. He would show the black border, the edges of his negative. He contrasted the white background against the black edge of the film in a way that was very radical. It made the pictures very tough and aggressive. Furthermore, bodies would be sliced, feet cut off at the ankles, heads cut off at the crown. He didn’t use flattering, chiaroscuro lighting. And he was fascinated by age. He had this wonderful expression called avalanche. He would describe seeing age descending on a person like an avalanche, covering them over. So Avedon took great care to photograph the folds of skin, wrinkles, and moles, all with a very sharp lens. And that was also very radical. Traditionally portraiture idealizes its subject—and gives some sense of their clothes and surroundings. Avedon dispensed with all of that. It’s hard to overemphasize how radical that kind of portraiture was at the time.