Poetry

Anne Carson Punches a Hole Through Greek Myth

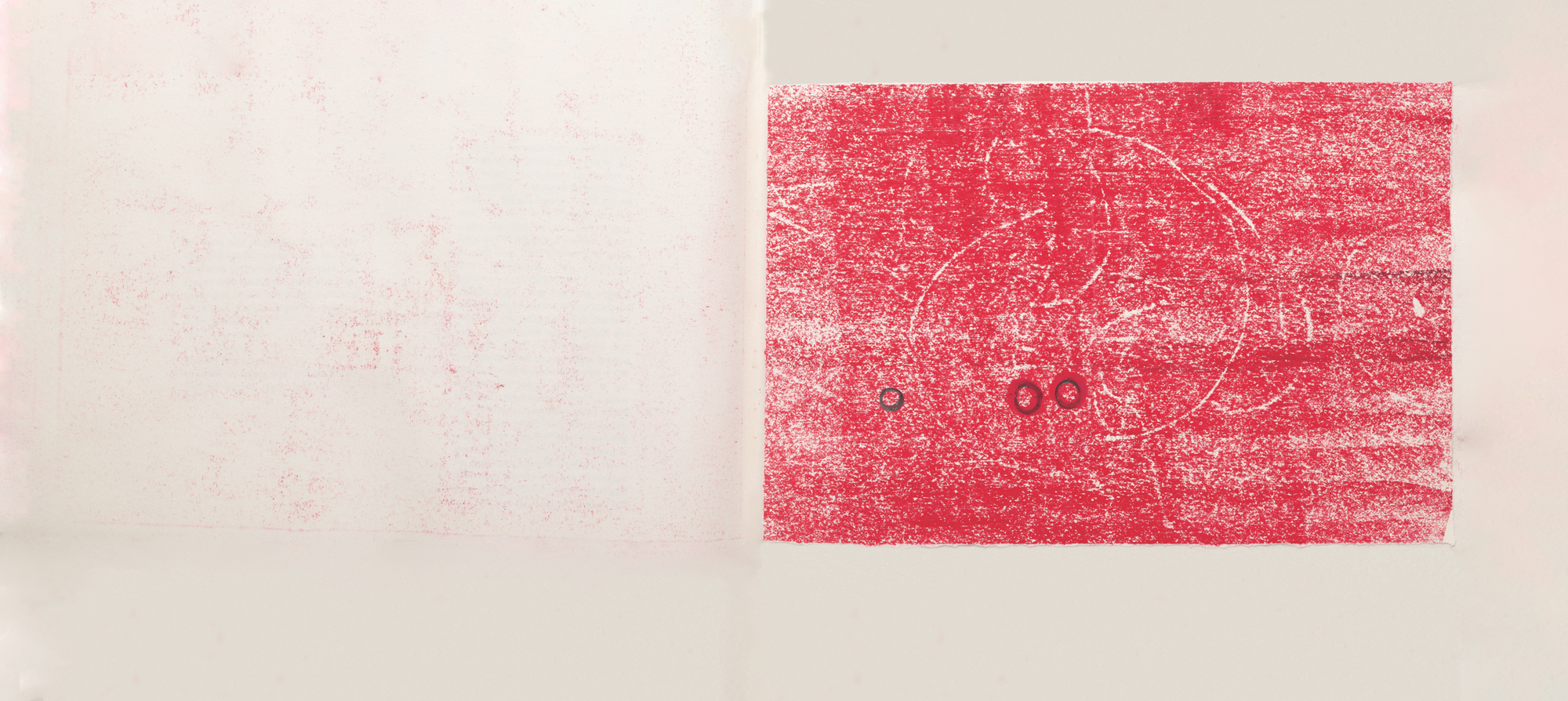

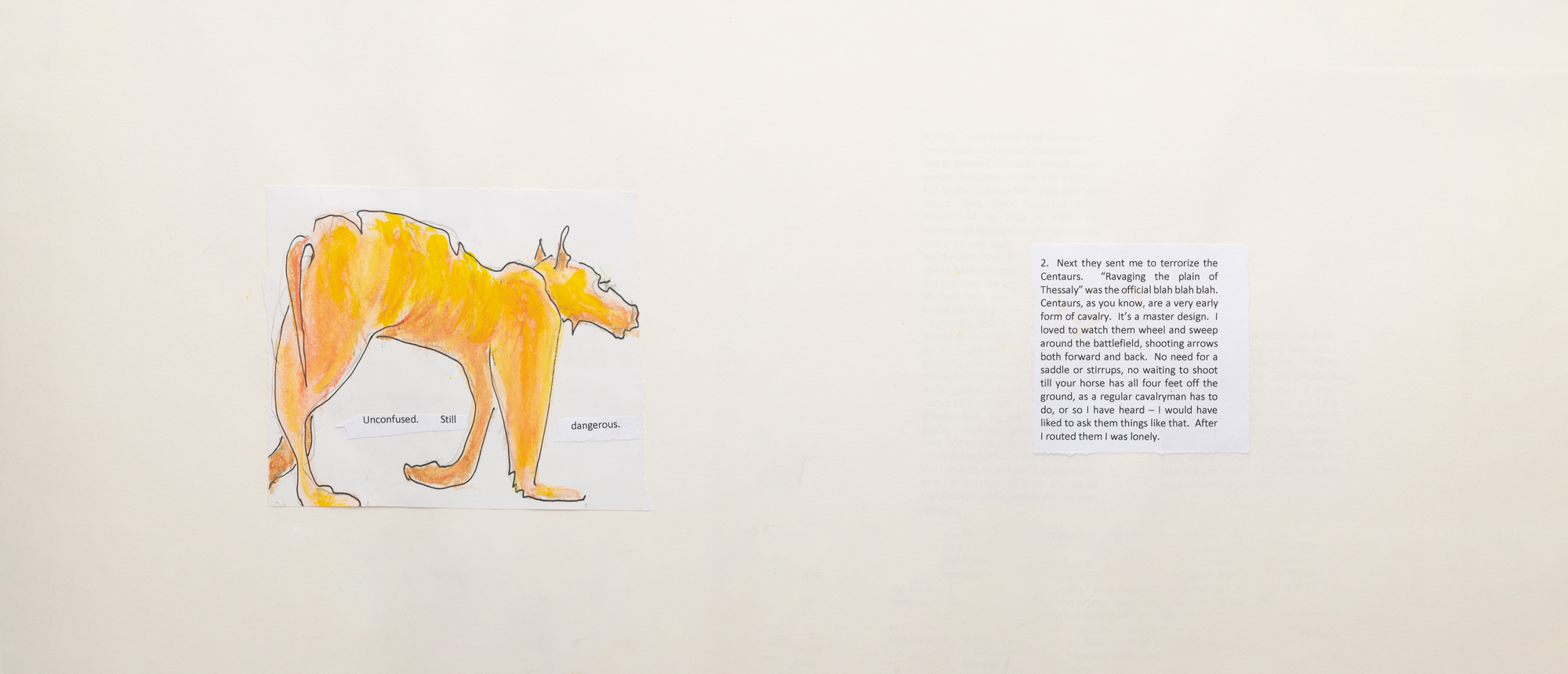

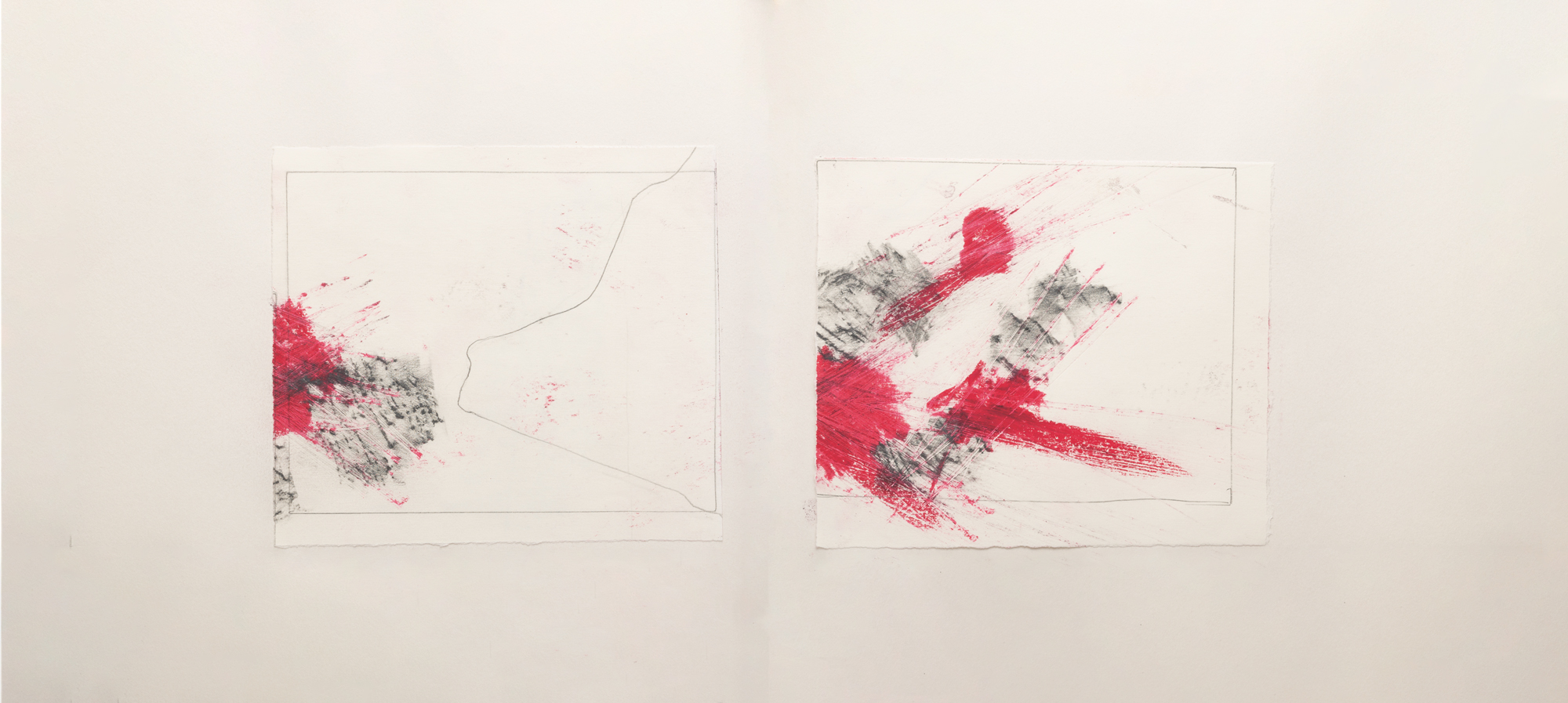

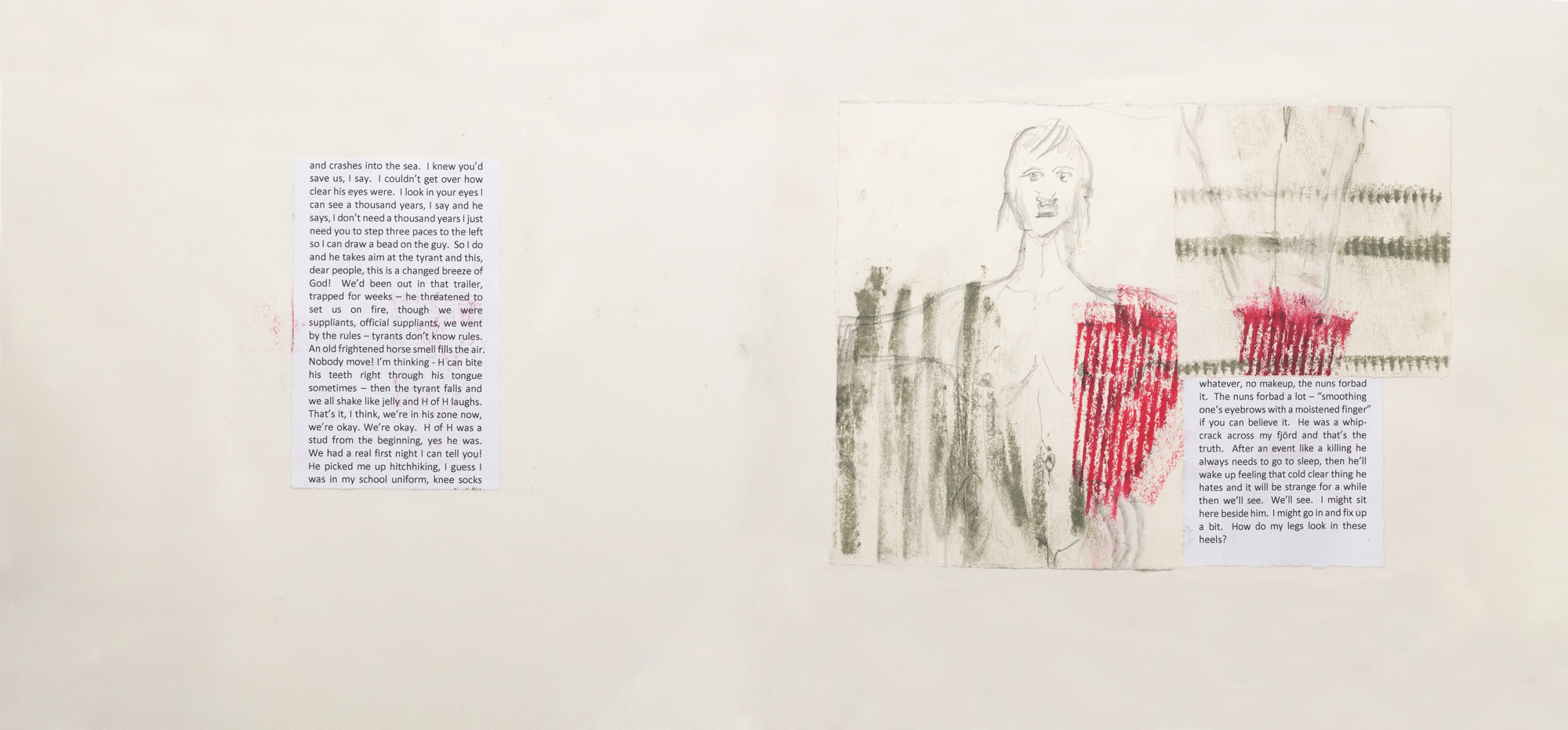

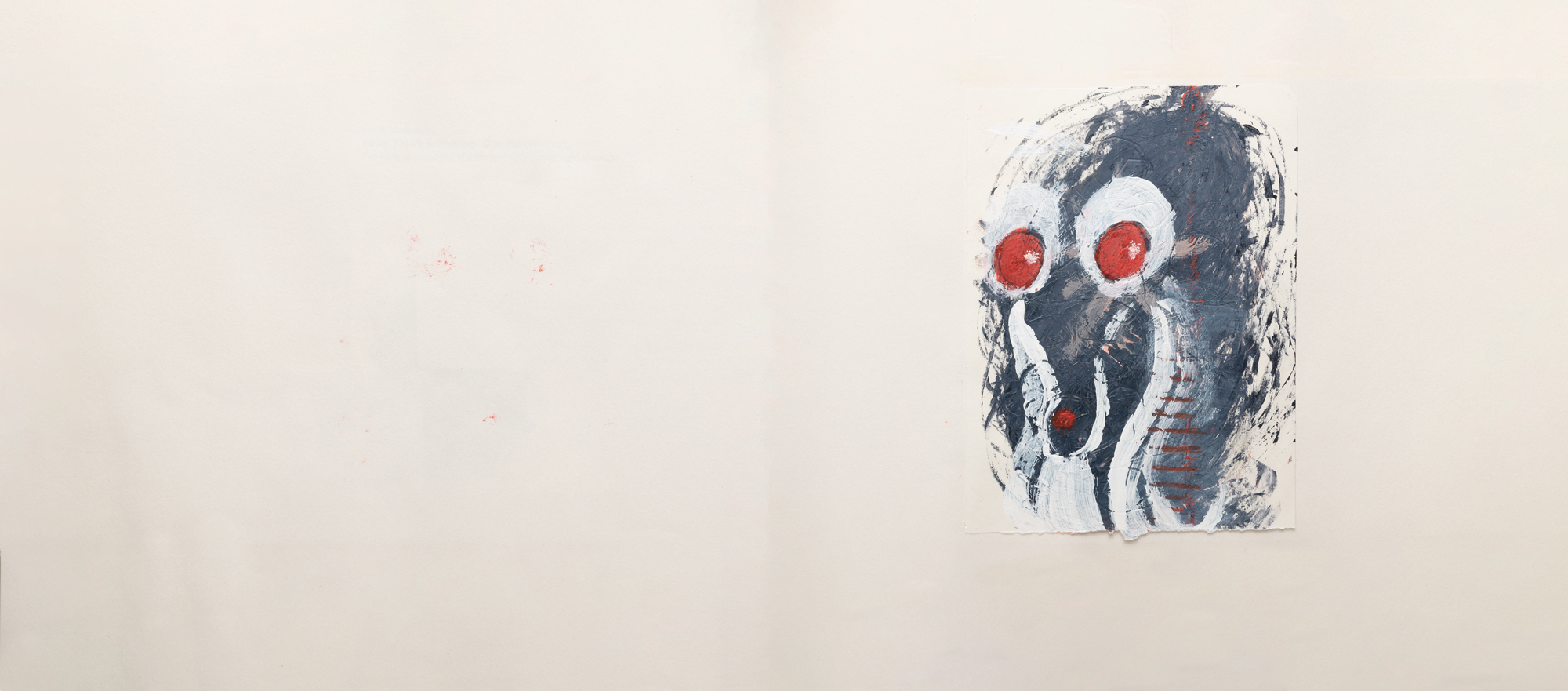

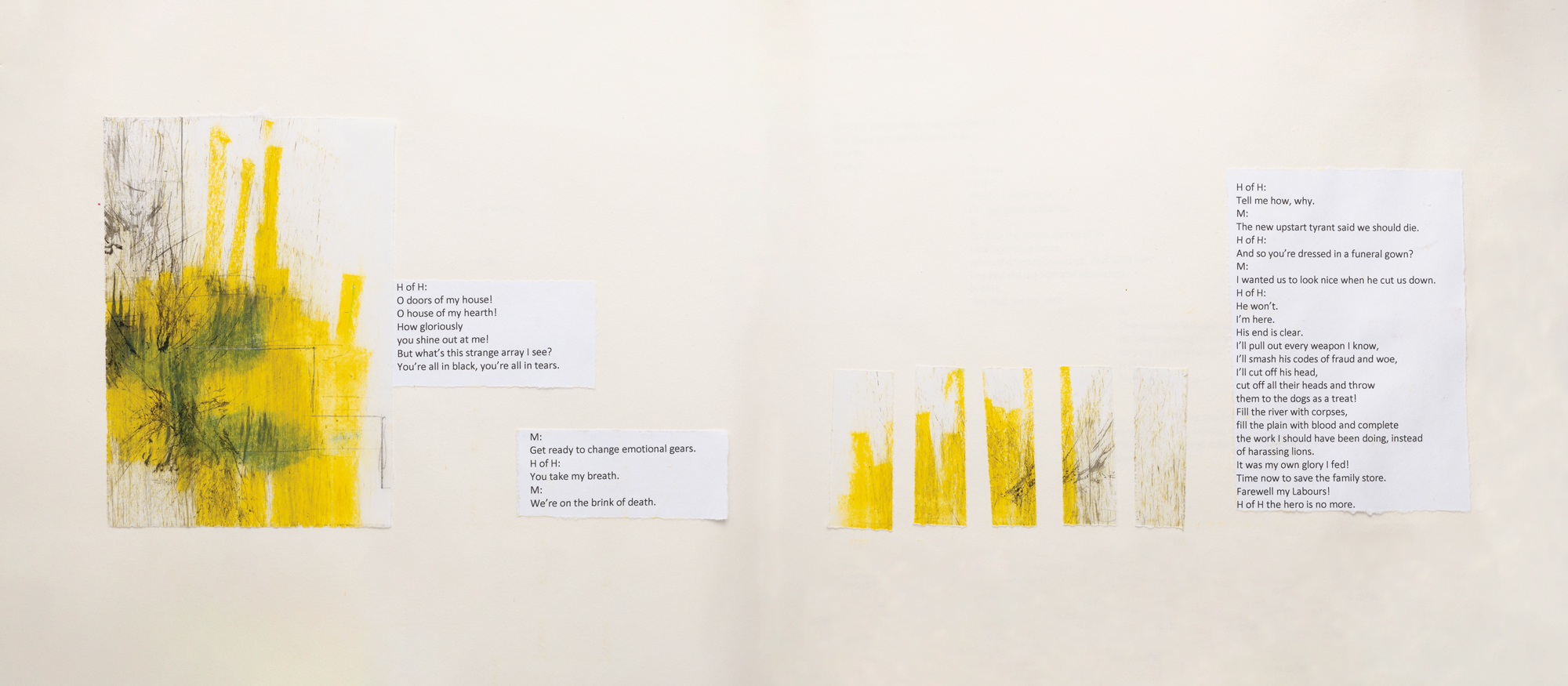

In her 2019 poem “Sappho Drives Upstate (Fr. 2),” Anne Carson depicts a soothing pastoral scene of two white horses in a field—a timeless, bucolic vignette. Then the last two lines arrive like a shock to the system: “All this—you tore a hole, pushed your arm through, hit the switch.” This sentence could serve as a warning label (or intellectual advertisement) of what the 71-year-old Canadian poet does to the classics, ripping them out of the past, shocking them back to life as if with electrical voltage, bringing the monsters of Greek myth to walk among us, slouch, punch, kiss, go back to bed, kill. Carson is an oracular figure especially among gay readers thanks to her 1998 “novel in verse” Autobiography of Red, which reimagines Geryon, the monster that Hercules slays in his tenth labor, as an awkward, vulnerable gay teenager in love with his hunky boyfriend Herakles. It remains to this day one of the most complex and loving portraits in contemporary queer fiction. Carson has returned to Herakles and Geryon more than once in her radical work, most recently in H of H Playbook, rejiggering Euripides’s 5th-century BC tragedy in which the hero returns from his labors only to succumb to madness and murder his entire family. The book also features the poet’s work as a visual artist, mixing her dialog with drawings produced during a stay in Iceland. The pages are frenetic accretions of text, mark-making, and erasure; abstraction and figuration rendered in chalk, acrylic paint, pencil, and eraser. In 2018, Carson appeared in a film by British artist Tacita Dean, reading from a poem on Antigone. This past October, the poet, who lives and teaches in Michigan, spoke on Zoom to Dean, who happened to be tackling her own adaptation of a classic: spearheading the costumes and design for the London Royal Ballet’s “The Dante Project.” — CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

———

ANNE CARSON: How is your ballet going? Are you still spraying the dancers with chalk?

TACITA DEAN: I am. In two acts—“Purgatory” as well as “Paradise.” It’s quite full-on. Well, you’re more used to that theater stuff than I am.

CARSON: Yeah. Some people like it, some people don’t.

DEAN: It’s funny how this kind of project completely devours you.

CARSON: Are you the one in charge of all the decisions?

DEAN: No, I’m just set design and costumes. But I’m a bit stressed because I’ve made a film for “Paradise” and yesterday we did our first run-through, and up went the orchestra pit lights and they bleached the film into muddiness. I went, “No!” And they were saying, “The musicians have to have this amount of light, unions.” And so, even in paradise, there are unions and bureaucracy.

CARSON: That’s good to know.

DEAN: As your new book proves, you’re way more inventive than any artist I know. It’s very daring—a page that’s just covered in the remnants of wax crayon.

CARSON: It was so fun to do. Then you can’t lose it because it was so fun to do. I credit New Directions for finding somebody who can scan it to make it look good and then print it.

DEAN: The last time we talked, you said you were drawing. Did you work on this project when you went to Iceland?

CARSON: We rented a place and there was a spare room, which became mine. When you have a room of your own, you can work. So that’s what happened. I thought, “What can I do in this room?” And then there it was. Virginia Woolf was right about that. Just a room where you close the door and something will happen.

DEAN: And you’ve continued to draw since, right?

CARSON: Yeah, even more so because writing seems kind of pointless in the contemporary world. I like drawing. I don’t know if you find drawing more frightening than writing, but I do. It’s more revealing.

DEAN: I agree. I don’t think I’m capable of just sitting down and letting myself draw. I’m too self-conscious these days, which is a tragedy. It’s a fear of failure to actually sit down and make a mark. I used to be able to do it. It’s something I lost with age. Or lost with a level of professionalism.

CARSON: It’s true. There’s a lightness to it that you lose as you become an artist with a capital A.

DEAN: Yeah, whereas writing for me is the opposite. I feel less self-conscious if I write something. I thought you’d feel the opposite.

CARSON: I think writing after many years becomes a place you can hide. Because you acquire a certain amount of craft, it allows you to do something while not revealing yourself. Whereas with drawing, every mark you make reveals yourself. You can’t cloak that in technical brilliance.

DEAN: Do you ever purposely try to trip yourself up in writing? You have this craft and know the places to hide. But do you ever want to expose yourself ? Are you aware of your own craftiness?

CARSON: I’m too well-defended. But, yes, sometimes it would be preferable to dig a little more into the raw thing.

DEAN: And you can dig into the raw thing when drawing?

CARSON: Well, that’s a deflection. There is more of a raw thing in words, but I can’t face that. So going sideways into drawing is a relief. But then, it also has these aspects of self-revelation that are scary. On the other hand, once you get going with a drawing, it’s so fun that it erases all that hesitation. The moment of wiping chalk onto the board is so exhilarating.

DEAN: Yes, when you forget you’re doing it, when it’s just beneath the conscious level. It’s really hard to do that.

CARSON: It is. I guess we’re supposed to live consciously most of the time for practical purposes.

DEAN: One line I use a lot is, “Dirt is matter out of place.” I borrowed that from you.

CARSON: I borrowed that line, too. [Laughs]

DEAN: And Julie Mehretu just named her new shows in Berlin and Spain Metoikos, which is borrowed from me, which is borrowed from you, which is borrowed from Sophocles. It’s traveling. You set off a chain reaction.

CARSON: It’s my hope. Greek is a reverberant language. But it’s a funny thing about works of art. When you make a thing, all the way through you’re thinking, “What’s to become of it?” I’m not the kind of person who can write a book and put it in a drawer and say, “Well, that’s an accomplishment. How nice. It doesn’t matter if it ever gets published.” I have to think of where it will go. Do you always need a place for the thing to end up, like a gallery or a show, or something that you know is the endpoint of the work?

DEAN: That’s what I miss from when I was younger, the ability to pasture without steeple-chasing the whole time. To just do a bit of grazing without purpose.

CARSON: Do you think some of that is the result of the pandemic, and just being in a closed room for months on end? Because time changed for me. Every day was endless and yet also too short with no middle. It felt like being in an igloo with a lot of snow outside and nowhere to go. Time had a different texture, and I don’t know exactly what that was. But it made the work feel different. And it made it seem more pointless to me, frankly. Partly because in the writing world, as soon as the pandemic got going, everybody was publishing COVID journals.

DEAN: Or drawing self-portraits every day. It was such a nightmare.

CARSON: It was. But then my own writing kept disappearing down that hole, because what else do you have to think about when you’re in your room day after day without seeing anyone? So yeah, there was a kind of extinguishing feeling there.

DEAN: It was quite frightening. Initially, it was like, “Whoa, we get two weeks off from doing anything!” And then it became endless.

CARSON: Yes, endlessness involving a lot of disinfectant. Speaking of COVID journals, a cheesy thing I started doing during the pandemic was making a gratitude list. You know, that psycho-therapeutic mechanism whereby at the end of the day you try to think of all the things in the day that you’re grateful for, to counteract despair and depression. As cheesy as it is, it’s really effective. I liked doing that.

DEAN: How micro-detailed did you go? Was it like, “I’m grateful for my cup of tea this morning,” or “grateful for the blue jay that just flew past”? Things like that?

CARSON: The more micro it is, the more beneficial, I found. You just go back into these little meaningless delights of everyday life, and it makes you feel like a Buddhist.

DEAN: How many things would it be on average per day?

CARSON: It depends on how much time you give it. You allow yourself however much time you have and need at night. Just 5 minutes or 30 seconds. I don’t think it matters how much. It just matters getting into that groove of thinking of the world as—

DEAN: No, it wasn’t a general question. It was a question about you. How long were your lists?

CARSON: I would say on average, 17 items.

DEAN: That’s impressive. Any days where you were totally ungrateful?

CARSON: There were days I forgot to do it, cloaked in my dismal self. But it wasn’t hard. That’s what surprised me. It wasn’t hard to do.

DEAN: I should do that. I’m grateful if they fix the lights in the pit. So you’re in Ann Arbor. Do you still write in a clutter-less room? I remember your writing room being very minimal.

CARSON: In theory. Of course, clutter seems to attract itself over one’s lifetime. Do you not like to be in an empty-ish space?

DEAN: I long for that. But Mathew [Dean’s husband, the artist Mathew Hale] keeps things. And I’m a bit the same. I’d love to be someone who can live minimally, but I’m not. I’m continually, continually, continually dealing with too many things on every surface.

CARSON: Is it a Francis Bacon kind of spectacle, with the layers and layers of old art ideas piling one on the other? Now I have drawers of drawings.

DEAN: I mean, what do you do with doodles? I don’t love my doodles. But then again, I can’t quite dump them either. But I have a great admiration for those who can achieve a domestic minimalism. It must bring a sort of clarity. I think I’m too sentimental.

CARSON: And it’s about continuity. It’s also parts of your former self that need to be cleared out.

DEAN: What about internal clutter?

CARSON: That’s even worse. Internal clutter is mirrored in the room. In my attempt to clean up my work room yesterday, I was putting away all my notebooks. Now, drawings are horrible enough, but notebooks are even worse, filled with a language and history and ideas. I have many, many, many notebooks. I once fantasized about ripping them up into little pieces and making a giant mural of all the thoughts I’d ever had in my life. But then I couldn’t decide how to use the backs of the pages.

DEAN: You could make a recto-verso mural. You could put it in glass.

CARSON: Oh, yeah. But that’s so complicated. I was thinking more, on the floor with a glue stick. Not in a factory. That’s the trouble. I have no technological skills of any kind.

DEAN: My problem is that I have these notebooks and I just never go back to them.

CARSON: Well, you should. It’s a little horrifying and a little bit fun at the same time. It’s like randomizing the thought of the present, and it doesn’t have to be notebooks. It can be other books in the rooms. I find it helpful. It kind of unlocks the moment for me.

DEAN: Do you ever get writer’s block?

CARSON: I did during COVID, and that goes back to the pointlessness. There’s so much writing in the world and a lot of it just seems like the same sentence.

DEAN: I’m sure your COVID diaries would be unlike anyone else’s.

CARSON: We’ll never have to judge, because they won’t appear.

DEAN: They’ll be transcribed into some other form, in some other era. I know you’re a lover of anachronism.

CARSON: There’s no such thing. All time is now.

———

Artwork images from H of H Playbook copyright © 2021 by Anne Carson. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.