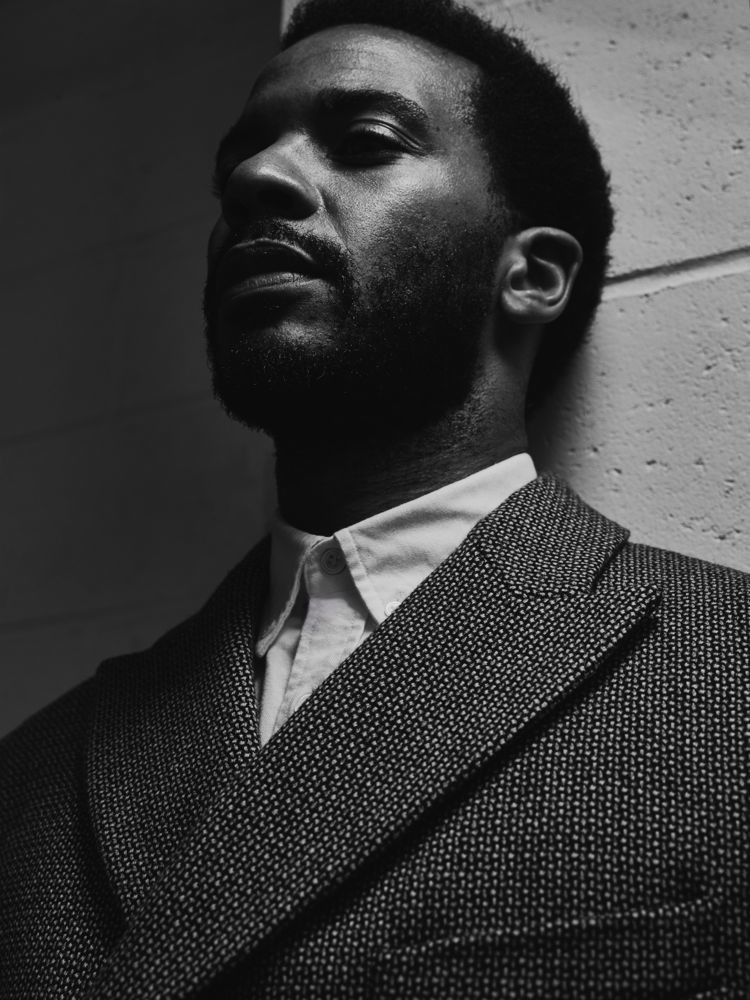

André Holland and the Tragedy of Doctor Edwards

ANDRÉ HOLLAND IN BROOKLYN, NEW YORK, JUNE 2015. PHOTOS: RAF STAHELIN/LALALAND ARTISTS. STYLING: MARINA MUNOZ/LALALAND ARTISTS. GROOMING: LAURA DELEON FOR CHANEL/JOE MANAGEMENT USING CHANEL HYDRA BEAUTY NOURISHING LIP BALM AND CHANEL LES BEIGES. STYLING ASSISTANT: ANITA LAU.

There is plenty of anguish in Steven Soderbergh’s Cinemax period series The Knick. At the end of the first season, the show’s protagonist, Doctor John Thackery (Clive Owen), is using heroin to overcome his cocaine addiction. Cornelia Robertson (Juliet Rylance), the intelligent, independent, and compassionate daughter of the Knickerbocker hospital’s main benefactor, has just been married of to a man she does not love, whose father has already started making advances on her. In an attempt to save her lover Thackery from himself, young Nurse Lucy Elkins (Eve Hewson) has been branded a whore. Irish nun and nurse Sister Harriet is in prison for performing illegal abortions for women in need. Doctor Gallagher’s wife Eleanor has been locked away in a draconian mental hospital. And Algernon Edwards (André Holland), the hospital’s only non-white doctor, is starting barroom brawls to alleviate his professional and personal frustrations.

That none of this feels melodramatic is a testament to Soderbergh and the depth of the characters he has created. Each misfortune feels like a tragecy of the time rather than a ploy for ratings. Afterall, The Knick takes place in New York City at the turn of the 20th century: a bad time to for women, people of color, addicts, and the mentally ill.

“You look at a guy like Dr. Edwards and he has so much potential and so much ability, yet it’s not going to happen for him—you know it’s not going to happen for him,” says Holland. “That, to me, is one of the real tragedies of the show,” he continues. “It’s a reminder of how far we as a society still have to go.”

Now 35, Holland began his career on the New York stage before shifting over to television with roles on the one-season sitcom Friends with Benefits and 1600 Penn and films such as 42, Black or White, and Ava DuVernay‘s Selma. After Season Two of The Knick premieres tomorrow, Holland will begin production on Barry Jenkins’ new film A Contract with God.

EMMA BROWN: I’ve watched the first few episodes of the new season of The Knick, and things aren’t going very well for anyone, really.

ANDRÉ HOLLAND: [laughs] Welcome to The Knick. Things just get worse and worse.

BROWN: A character from Algernon’s past reappears and changes the dynamic of his life quite a bit. When did you find out about this character? Was this something you knew about in the first season?

HOLLAND: No, I had no idea. I think maybe the writers had plans for it, but I had no idea at all. I didn’t find out until I was given the script and I was reading along and had to double back to make sure I’d read what I thought I’d read. I was as shocked as everybody else. But what’s great about it, I think, is that over the course of the season, you really get to see this couple grow and develop, and by the end they become a couple that I think are really well suited for one another. Opal brings out in Algernon things that Cornelia really couldn’t have, because she understands him in a way that I don’t think Cornelia was able to.

BROWN: Do you think Opal is a good influence on Algernon?

HOLLAND: Hopefully she will be. She’s quite fiery at the beginning and stubborn, but I think by the end, when she comes to realize what his life has been like in New York, she changes and he changes. I think they meet each other in a really nice place by the end.

BROWN: One of the things Opal and Algernon first fight over is Algernon’s relationship with the Robertson family. Obviously the Robertsons have helped Algernon in his career—they brought him to the Knick—but do you think the relationship has held Algernon back emotionally?

HOLLAND: I don’t think so. He may have been sheltered from what was going on in New York, so in that sense he may have been held back emotionally. But they helped him so much. His parents wanted the best for him, and they are the ones that are really responsible—his parents and the Robertsons—for him being able to live up to his potential. I think there is still some emotional growing up he needs to do in terms of his awareness of what the racial politics are of the city, but he’s a sharp guy and I think he catches on pretty quickly. He grew up a lot in Season One.

BROWN: Tell me how you got involved in The Knick? I know you read and liked the script and then met with Steven and [producer] Greg [Jacobs]. Was that it?

HOLLAND: I read it and loved it. I sent in an audition tape, which they liked, and then they invited me to meet with everyone. Actually before they invited me, I had to send an additional tape with some different scenes. Then we got together and had lunch and spoke for a while. Shortly after that, they told me that I was the choice. It was an intense week and a half, but it all sort of happened within a week and a half or two weeks.

BROWN: Is that normal?

HOLLAND: It’s pretty normal. Things maybe take longer usually when it comes to TV—especially network TV. There are usually multiple levels that you have to go through in terms of the casting director, the producers, the studio, the network, reading with other people. But in this case, Steven had a really clear idea about what he wanted, and obviously Cinemax and everybody involved trusts him and his tastes. It was pretty quick, and he was pretty quick to pull the trigger and everybody got behind him. Carmen Cuba, who’s the casting director, was instrumental in helping me get the part because she did something which casting directors rarely do—she reached out to me and met me for a coffee before I went to meet with Steven to just make me feel more comfortable and to tell me a bit about the work and who I was going to be meeting. She really was a huge advocate for me. I’m really, really grateful to her for that.

BROWN: Do you feel like The Knick has changed your career?

HOLLAND: I think so. It definitely raised my profile. Working with people like Steven and Clive and Greg and that whole team, I think people in the industry are looking at me in a slightly different way—working on such a high caliber show lets people that know that I can be trusted, frankly, with bigger parts and to work with better people. There have definitely been some things that have come my way that wouldn’t have before. But it’s still very much a grind to find quality parts. It’s been quite sobering, actually, to come out of this and still be searching intently for good material. There just isn’t a lot of it out there, or at least not that I’ve had access to.

BROWN: Do people ever come up to you on the street about The Knick? Do they call you Dr. Edwards, Algernon, Algie, or by your actual name?

HOLLAND: People do come up to me quite a lot. I get called all of it. I rarely get called my name; it’s usually “Hey, Dr. Edwards!” or “Algernon.” The most common thing is, “You’re the black doctor on that show!” [laughs] I’ll take any of it, because I’ve definitely been called much worse things.

BROWN: If you could play another character on the show—regardless of race, gender, or age—whom would you want to play?

HOLLAND: I love my character. I don’t think there’s another one that I’d rather play, and that’s rare. In 42, I was a little bit like, “I wish I was playing Jackie Robinson.” But in this case, I couldn’t be happier with this part. I think it fits like a glove. I appreciate all the other parts, but in my opinion I think I’ve got the best one.

BROWN: Did you feel that way about Selma—wishing you had a chance to play Dr. King? Or would it have been too much pressure to play someone so revered?

HOLLAND: Oh no, not at all. David [Oyelowo] did a great job with that part, but I’m a competitive guy, and I’m a trained actor, and I would have loved to have had the opportunity to play that part as well. It’s interesting. I read something the other day, an article came out talking about the rise of the black British actor saying that the reason there are so many black British actors getting so many big jobs in Hollywood is because there is a lack of trained black American actors. The article was talking about Selma in particular, and why David and Carmen [Ejogo], the British actors, were playing the leads. It’s just so wrong and ignorant, I think, for people to even put that idea forward. There are so many trained actors who are capable of playing those parts, and I think it’s a shame that people are even having that discussion.

BROWN: That’s weird. I’ve talked to a lot of black actors who went to drama school and are formally trained.

HOLLAND: Exactly. I went to a conservatory program for four years and then NYU for three years for a masters in acting. Most people do—most of my friends did. There are so many brilliant, trained actors of color in America. If you just think about it, every year in the spring Julliard and NYU and Yale and hundreds of schools across the country graduate classes of trained actors, and in those classes are actors of color. So to say that there aren’t enough actors of color is factually inaccurate. But more than it being inaccurate, it’s also really divisive and damaging and frankly disrespectful to the actors who are out here working. If you look at Selma alone, David played the lead, but he’s surrounded by actors who are trained and come from the theater and have been working for years and years. It really sometimes feels like a slap in the face to hear these British actors say that.

BROWN: Do you think going to drama school was important for you?

HOLLAND: Absolutely. It was instrumental. I learned so much. All the craft skills that I have, I feel like I developed and honed in drama school. It’s the most important thing for me.

BROWN: Was there one thing in particular that you are particularly glad you learnt before going out into the professional world?

HOLLAND: I think working on Shakespeare was a big part of my time at drama school. I’m so glad that I got to know Shakespeare and got a chance to play great parts in Shakespeare, because it really teaches you—or taught me, anyway—everything. When you’re playing Shakespeare, it forces you to think and feel and speak all at the same time, which really is what acting is. It expands your imagination and expands your size of thinking. I would say working on Shakespeare and learning about Shakespeare was the big takeaway for me.

BROWN: What’s your favorite Shakespeare play?

HOLLAND: Oh, man. That’s hard to say. I love Twelfth Night. I love Hamlet, of course—I think every male actor loves Hamlet. The Tempest. I also love a play that a lot of people don’t necessarily love, Richard II.

BROWN: What makes you like Richard II?

HOLLAND: The poetry. The language of Richard II to me is astounding. Some of the speeches that he does—there’s one where he’s contemplating his own mortality and it starts, “I’ve been studying how I may compare this prison where I live unto the world,” and it goes on and on and on, and it’s some of the most beautiful language I’ve ever heard. That one’s very near the top of the list.

BROWN: I heard that your first ever time on stage was when you were 11 in the musical Oliver. Is that true?

HOLLAND: Yeah. I’m from Alabama and my mother started me in this summer drama program, I think mainly to keep me out of trouble. At the end of every summer we’d put on a play, and Oliver was the first one.

BROWN: Who were you?

HOLLAND: I honestly don’t remember. It was so long ago. I think I was just one of the little urchin kids—one of the boys who was living at the home with Fagin.

BROWN: Can you sing?

HOLLAND: I love to sing. I’m definitely not a very good singer, but when I’m in my shower I get down for sure.

BROWN: Do you come from quite a creative family?

HOLLAND: My family is pretty blue-collar hardworking people. My father is extremely poetic and in a different life probably would’ve been a poet or a writer. They’re all really creative people, but their professions are not creative.

BROWN: Does your family watch The Knick?

HOLLAND: They do. Every Friday when it comes on they have a little party. They invite family over and watch it and call me every five minutes: “What was that? What did he say? I can’t believe that! Why did he do that?”

BROWN: Do you warn them if something particularly gruesome or shocking is going to happen?

HOLLAND: No. I warned them on the very first episode with that C-section. I told them, “Don’t eat before you watch this one.” But from then on they were cool.

BROWN: I was thinking about when Dr. Edwards would have been able to, not just achieve his full potential as a doctor, but to do so and have it not be an anomaly. It’s quite difficult to pinpoint a time.

HOLLAND: I’ll be honest. I don’t know if it’s happened yet. I think there’s still this idea—there’s still so much shock around people of color being in certain positions. I don’t think we’re there yet.

SEASON TWO OF THE KNICK PREMIERES TOMORROW, OCTOBER 16, ON CINEMAX