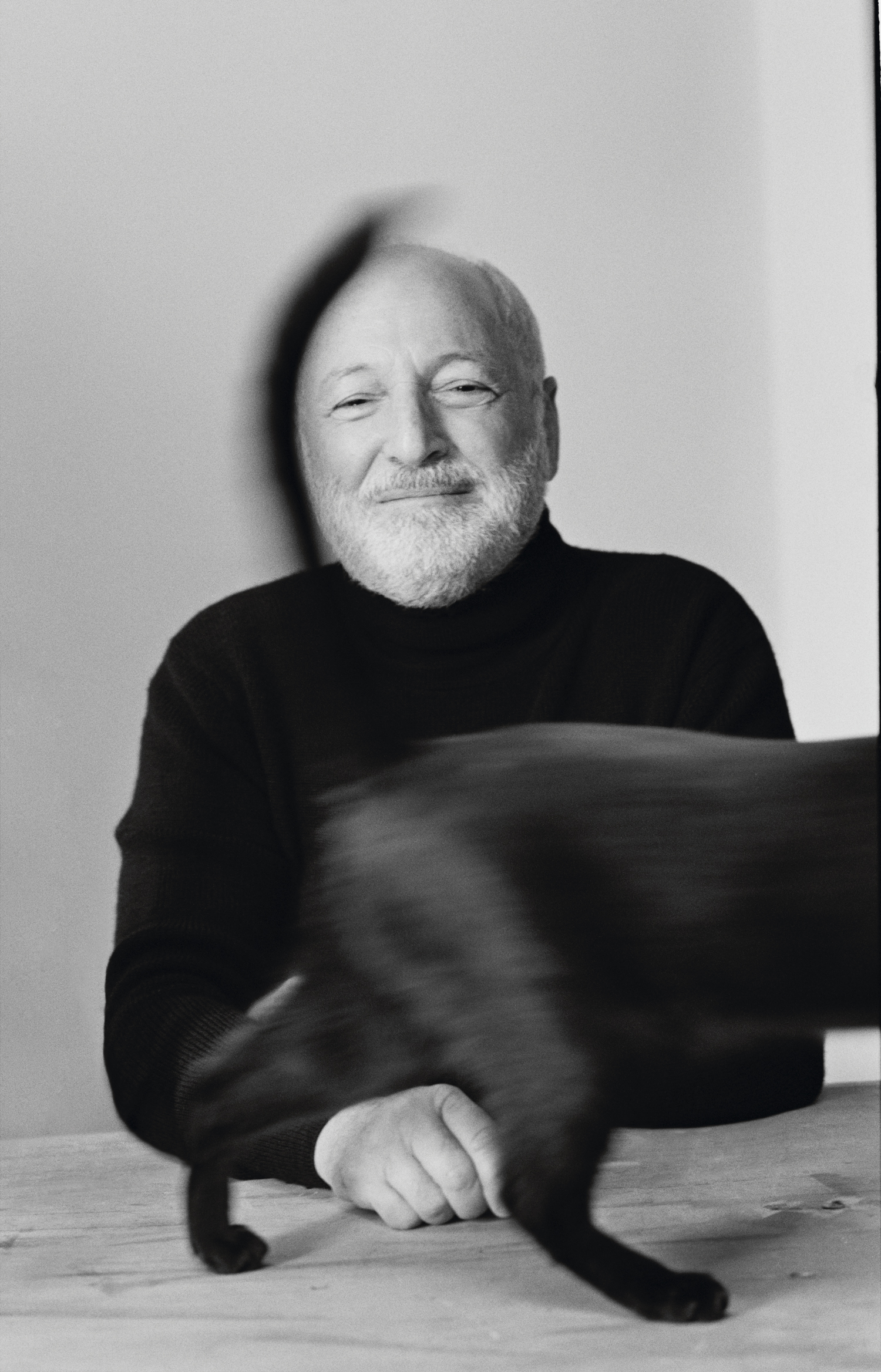

André Aciman Doesn’t Want to See Elio and Oliver Folding Laundry

Sweater by BALENCIAGA.

For years after its publication in 2007, André Aciman’s Call Me by Your Name was traded like a secret among friends—particularly in gay circles. Then, in 2017, the Italian filmmaker Luca Guadagnino brought the novel to the screen—and with it the leading characters of Elio and Oliver, memorably embodied by the actors Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer. Aciman’s gifts for conjuring romantic longing, sexual awakening, and heart-break were no longer secrets. The cult favorite was reborn as a classic.

Many authors would be reluctant to revisit characters who have grown so large in the cultural imagination, particularly ones whose narrative arc was so perfectly framed by a single Italian summer. Discovering what happens to Elio and Oliver might seem more the work of fan fiction than literature, but Aciman’s bravery extends beyond sex scenes. In fact, it was always the 68-year-old, Manhattan-based author’s plan to return to the characters of Call Me by Your Name and mine their fates for fresh insights on the human soul. This month, Aciman releases his long-awaited sequel, Find Me (FSG).

Set decades later, the novel follows the separate paths not only of Elio and Oliver, one a rising concert pianist, the other a semi-disgruntled academic, but also of Elio’s recently divorced father, Samuel, who opens the book on a train ride to Rome to visit his son. Each protagonist—distinct in their age, career, location, obligations, and sense of unfulfilled desire—is catapulted into a new terrain of romance and exploration. Find Me is particularly inspired by Aciman’s passion for classical music. As with his last novel, 2017’s Enigma Variations, whose very structure felt like musical form, the heart of the new book echoes all of the secret notes, tempos, and rhythms located in a single score. This is not a book for the cynical philistine or for anyone who dreads a night at the symphony. Aciman spoke to his friend, the American classical pianist Jeremy Denk, about resurrecting a love story, finding inspiration in the classics, and why you won’t see Elio and Oliver folding laundry on a Sunday at home together.

———

JEREMY DENK: It’s a delight to be reading your book.

ANDRÉ ACIMAN: Did you notice the novel’s second section has to do with a conversation you and I had about a year ago at a café on 110th Street? Elio meets an older gentleman and this gentleman gives him a score, and Elio looks at it and begins to realize what it is. That scene stems directly from a discussion we had about Mozart and cadenzas and how, by the use of a cadenza, the composer leaves room for the soloist to improvise whatever they want to play within that larger piece.

DENK: I remember. You asked me if it was plausible, from a musician’s point of view, to bury another score within a piece.

ACIMAN: That’s right. I wanted it to be a form of excavation, where amid this Mozart and bits of Beethoven, Elio uncovers a Jewish prayer. It works like a buried message between two people. It was also a way to show that there is a whole history behind a single piece of music—catastrophes and disasters and tragedies that happen and get smuggled into a score.

DENK: You used the Kol Nidre. I’ve played various versions of it myself. I was particularly curious about how you merge this idea of the cadenza with a pretty intense love story.

ACIMAN: Because the cadenza is the moment for the soloist to improvise in music, I thought of it as being the same as a character needing to improvise in life. You don’t have a set script in life. You see what you’ve been given and try to make something out of it. For Elio, he’s not accustomed to an older man and suddenly something is blossoming between them. The cadenza is an invitation to improvise, to just go with it and see where it leads. And the cadenza is also a moment to dig in and explore. Every moment in life has a history to it. With Elio, there is this whole history with Oliver that precedes this older man. That brought me back to the idea that life is always an archeology of moments from our boyhood, our adolescence, our college years—everything gets stacked together. It’s the past that defines who we are in the present. In Find Me, the father keeps revisiting places from his past. Revisiting a place means incorporating all of those previous visits into the current one. It’s a profound act of spiraling, circling, or remembering, and what is more profound than that? For Elio, that holy spot is the wall where, one drunken night many years ago, Oliver kissed him. He goes back to that wall and he says, “If I look at it long enough, Oliver is with me.”

DENK: Each section of Find Me deals with a moment of falling in love—or that improvisational process of falling in love. And it’s a very body-oriented love that you write about.

ACIMAN: Yes, it is body-oriented. Everything I write is anchored in the body. But of course the body is very, very deep. It’s not just the skin. It’s the voice. It’s the energy of the other person. But I do think the mystery of what happened between one individual and another is what draws my attention. And it’s really always such an unfathomable mystery: What happens when X meets Y? It’s never simple.

DENK: I guess I’m not used to having classical music and sensuality so interrelated. [Laughs] I’m grateful for the sexification of classical music and the way that it keeps coming through in the act of piano playing in your work—it’s presented as such an intimate moment of sharing between two people.

ACIMAN: Music—I think more than literature—is a form of transcendence. Music is how we lift off when we want to reach the highest spheres of beauty. I think that’s why I keep going back to classical music. Many people say to me, “Enough with the classical music. Can you bring in something that’s more modern so that people can be more in touch with it?” But for me, classical music defines the search for beauty and soul.

DENK: There is a sense in your book of characters who genuinely care about art.

ACIMAN: I want to tell stories about how people arrive at this magical moment, where mind, body, spirit, and history all bloom and it doesn’t always last. That might be the tragedy of our lives, its evanescence, but it’s beautiful when it does happen. And the word I use in my book is “intimacy.” The ability of two people to be intimate with one another is no different than the pianist’s intimacy with music.

DENK: You’ve returned to these characters at a much later time in their lives. Did you always think you’d revisit this story?

ACIMAN: I’d always wanted to come back to them. I felt that at the end of Call Me by Your Name, I’d jumped 20 years too far ahead in filling in some of the story. I knew I wasn’t going to pick up right where I left off a year or two later, either. I did their youth. That was over, and they had moved on. That’s how I saw things. But I also wanted to take my time with them. I wanted to be slow in writing the sequel. I had other books to write in between.

DENK: Presumably you’ve had a lot of readers asking what happened to these characters, before and after the movie came out.

ACIMAN: A lot of people wrote me, wanting to know what happens to them. I’d say, “Your guess is as good as mine.” [Laughs] People even sent me sequels to the book that they had composed! And movie scripts! I told them I couldn’t read what they had written. I was already writing Find Me when I saw the film version of Call Me by Your Name, and I didn’t let the film influence the book at all. As a writer you have to shut the door on all that, go into the hovel of your studio or desk, and enter that world on your own. I certainly didn’t want people to think I was writing this sequel because of the film’s success. In fact, that might have frozen me up a bit in the writing process. But once I got Elio and the music aspect of his story, I knew where it was going.

DENK: Do you think you’ll make it a trilogy? Will we find them 20 years on after Find Me?

ACIMAN: No, I think it has to stop. To be honest with you, once you’ve solved a particular problem between two individuals, then you’re stuck with writing about their domestic life. I’m not good with that subject, because domestic life is something that happens in the present tense. It has its own series of mishaps and amorous moments, but it becomes too much like reportage. And that to me has no interest. I’m not a reporter of information. I like to see what people are dreaming of, even when they’re in the here and now. I mean, the last thing you want to see is Elio and Oliver doing the laundry on Sunday afternoon, folding blankets and towels. [Laughs] That doesn’t do anything for me.

This article appears in the fall 2019 50th anniversary issue of Interview magazine. Subscribe here.

———

Grooming: Clay Nielsen using Leonor Greyl at Art Department

Photography Assistant: Charley Parden

Fashion Assistant: Dominic Dopico