Alex Honnold

The first text message I get from Alex Honnold comes from a mountain ledge two-thirds of the way up El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. My hands sweat, picturing him wedged into a faint wrinkle of rock thousands of feet over the valley floor. Later, talking on the phone during his hike down the mountain, I ask Honnold about his earlier perch, and he says, “Had you seen the position I was in, you would have shit yourself.”

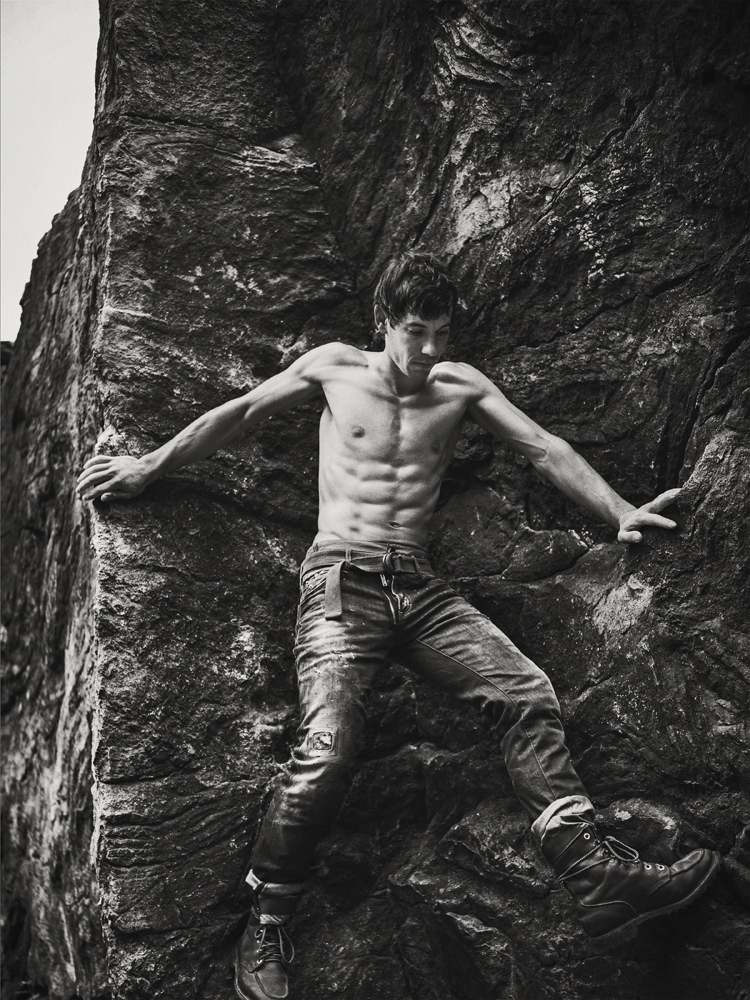

At 29 years old, Alex Honnold has become arguably the most well-known and widely respected climber in the world by ascending, without ropes, rock faces twice the height of the Empire State Building. His only equipment on these monumental climbs: rock shoes and a chalk bag belted around his waist. Any wrong move, any broken hold, and he falls thousands of feet onto jagged rock. As even a casual climber knows, these “holds” are not typically the four-finger jugs on a rock wall at a gym. In real life, on an actual slab, half your weight hangs from a fingertip crimped to a ripple in the granite; the other half rests on one big toe, trusting a chalk-covered divot not to flake away.

This style of climbing, for which he has been known since his 2007 solo of Yosemite route Astroman, and which only a handful of professional climbers attempt, is known as free soloing—free, because his upward progress is unaided by equipment; solo, because he is alone until he reaches the summit. Soloing is as pure, and as dangerous, as climbing gets, yet there are also practical advantages to this style. While a journeyman climber with cams, carabiners, and ropes can scale El Cap in a matter of days, Honnold flows up the mountain in hours. Even at his accelerated pace, Honnold’s ability to maintain focus, to forecast and replay the eight- to twenty-move sequences of each crux, makes each ascent more akin to a grandmaster playing chess than a skydiver seeking a rush. “I’m not thinking about anything when I’m climbing,” he says, “which is part of the appeal. I’m focused on executing what’s in front of me.”

Focus, for the Sacramento native, means survival. And thinking—wondering how he ends up on the side of a cliff day after day, for example—can paralyze a climber. “Uncertainty,” Honnold says, “is sort of the requisite for having an adventure, which is an important part of climbing for me. But I try to edge out uncertainty.” So he is rigorous in his preparations and humble in his approach. He focuses on “being intentional,” he says. “Working toward a goal. Doing things properly—in the right order. Thinking things through before you do them. I never set out to master the mental side of climbing,” Honnold says, “it’s just been a long, slow progression.”

Despite being sponsored by big companies like the North Face, Honnold lives simply. His primary residence is a 2002 Ford Econoline van with solar panels on the roof and energy bars in the cupboard. This van camping allows him to live with national monuments out his window, to maximize his climbing time, and to keep raising the bar for what is possible in his sport. During the week I spoke with him, he and a friend climbed seven different routes up El Capitan in seven days—that’s four vertical miles on routes that each take advanced climbers several days to complete—and set four speed records in the process. They are records Honnold himself will likely continue to write over himself in his high stakes pursuit of perfection. But high stakes bring high rewards, and I’d applaud him on his success, if I could only get my hands to stop shaking.