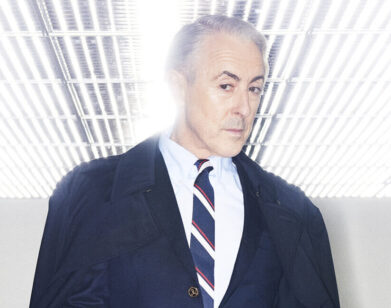

Aidan Gillen

PHOTOS: IAIN ANDERSON. STYLING: KITTY COWELL. GROOMING: THOMAS SILVERMAN USING M.A.C. COSMETICS. STYLING ASSISTANTS: RHYS THRUPP AND HARRIET RUSSELL.

“I would argue that it started with Twin Peaks,” says Aidan Gillen. We’re discussing the “golden age” of contemporary television, and where the Irish actor’s work on HBO’s The Wire fits into the timeline. “I would still hold The Wire up as one of the best,” he adds. “Not because I’m in it. It was like that before I came along.”

Gillen, who is now 49, knows how to pick a television show. After spending a decade in the London theater, he earned a BAFTA nomination for his role as Stuart Jones on Queer as Folk. From there, Gillen transitioned to films in L.A., a Tony-nominated turn on Broadway in Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker, and, of course, playing the ambitious Baltimore politician Tommy Carcetti on The Wire. For the last six years, he’s starred as slippery Little Finger on HBO’s Game of Thrones, which returns for a penultimate season this weekend. When we speak via phone, he is in Manchester, England, filming the fourth season of Steven Knight‘s stylish period crime drama, Peaky Blinders. While he can’t discuss his character, or any of the plot points, he’s happy to be involved. “I love Peaky Blinders,” he says. “I think it’s one of the best TV shows around at the moment—definitely one of the coolest … Steven Knight, the writer, is all over it, in the way that the writers or creators of my all-time favorite shows have been.”

Knowing when to move on is another important factor in the longevity of Gillen’s career. “One of the reasons I left London after Queer as Folk was because I wasn’t that comfortable with the attention or being called by a character name on the street,” he reflects. “Now I quite like it, and I’d rather be called by a character name than my real name—I’d rather have that buffer in there, and it means they believe what you’ve done.” A viewer’s relatively short attention span is something he regards favorably: “The good news is that if you find another role and do okay in it, they switch to that. It went from ‘Stuart’ to ‘Tommy’ to ‘Little Finger,’ and some other ones along the way. Within a couple of years, they forget who you are, and that’s also quite comforting.”

EMMA BROWN: Did you know any of the Peaky Blinders cast members before joining the show?

AIDAN GILLEN: A few. Cillian [Murphy], I know, not especially well, but I do know him going back a few years, casually, really. Ned Dennehy, who plays Charlie Strong; Packy Lee, who plays Johnny Dogs. Charlie Murphy, who’s a really great Irish actress who’s coming in this year also, I know because we’ve worked together before on a series called Love/Hate in Ireland. That’s probably it.

BROWN: Is the Irish acting scene quite small? Do you feel like you know most established Irish actors at this point?

GILLEN: It’s a small enough scene, for sure, which is one of the reasons I went to London in 1988, to open up a little.

BROWN: I know your sister Fionnuala is an actor as well, and two of your brothers are involved in film. When you all decided to go into the arts, were your parents excited? Or were they hoping that one of you would become a doctor?

GILLEN: I’m the youngest of six kids, and I don’t think any one of us was going to be a doctor. It wasn’t that kind of thing. Me and my sister, who were the youngest, were the first to get into it and the others came in later. We started at the same time in this youth theater group in Dublin. If you’re a parent of six kids, by the time the youngest ones are in their mid-teens, you’re kind of over fighting about what they want to do. I just had encouragement, actually. I started working straight out of school, so it was never an issue.

BROWN: What was your first professional role in London?

GILLEN: It was a play called A Handful of Stars, which was at the Bush Theatre [in 1988]. It is, and was, a new writing theater—they only produce new plays. It was formed in the early ’70s, and it’s moved now, but it was a tiny theater over a pub in Shepherd’s Bush and a real hotbed of talent and discovery. I came over there in ’88, did the show, and ended up moving into the house of the artistic director, Jenny Topper, because I needed somewhere to live. I lived there for three years and I used to see everything. I continued being around there into the ’90s. There were lots of exciting things there; they were doing the first performances of plays like Killer Joe by Tracy Letts. The first London performance of Trainspotting before the film had even come out was at the Bush. It was always an exciting place to be around. I did two or three plays there by the same writer, Billy Roche.

BROWN: I know you were on Broadway before you did The Wire. When did you first come to the U.S.?

GILLEN: I first worked in the U.S. in, I think, 1998 or 1999. I had done a series here in Manchester, actually, called Queer as Folk, and just what I said earlier about getting away from places—I like to do that. After that was completed and seemed like it was going to be successful, I decided it was time to get out. I came to Los Angeles to do an indie film called Buddy Boy and stayed for a while. I’ve been working in and out of there ever since. I’d say the longest stints have been when I did that Harold Pinter show, The Caretaker, and got cast in The Wire.

BROWN: Did you keep up with Charlie Hunnam between Queer as Folk and King Arthur?

GILLEN: I wouldn’t say we kept in touch, though we weren’t actively trying not to stay in touch. I didn’t see him much in the last 18 years. I was keeping an eye on what he was up to though, and I had an interest given that Queer as Folk was probably his first proper lead role. I’m not really quite sure what he’d done before that—I think a role in something set up in Newcastle called Byker Grove. I met him a couple of times [after]. He came over to our house—we were staying in Santa Monica. I met him in Edinburgh, maybe a few years later. Then I was in Montreal in 2001 shooting a TV series, and he was there working on a film called Abandoned, which was one of his first lead film roles. If we were in the same town, we’d meet up, but it seldom happened.

BROWN: When Queer as Folk came out, did you feel like you were going to be stuck as Stuart forever? And was that the first time you experienced that?

GILLEN: It was one of the reasons I didn’t sign up to do any more than 10 episodes. When it became successful, suddenly it was on the table that we could do loads. It was on my mind; I didn’t want to be as identifiable with one character.

BROWN: Do you ever audition anymore? When you get a role, is it generally because someone’s seen one of your other projects and reaches out to you?

GILLEN: I’ve never been good at auditions and I’ve never really gotten many jobs from auditions. I’ve done it loads, like every other actor, but some actors are good at auditions and some aren’t. I’ve never been that good at it. I can trace a direct line from whatever my latest job is to the first one I’ve ever had. The ones I’ve got from auditioning, I could count on one hand.

BROWN: Did your career feel like a very linear progression then?

GILLEN: Not really linear—kind of a pinball. That’s good—for me anyway.

BROWN: At this point in your career, how do you decide which roles to take on?

GILLEN: From early on, I tried to steer clear of obvious typecasting. That did come up early on; you play a certain type of character with success and other things come along that are the same and you can choose to do it or not do it. I’ve tended to stay away. I know that I have played a lot of similar characters as well as that, so I’m probably not doing it as much as I think I am.

BROWN: Have you ever taken a job where you didn’t love the character, or the project, but it seemed like the right move?

GILLEN: A couple of times. I haven’t done it because I thought people would see it, but that has happened a couple of times. You don’t always get it right; I am conscious of that and conscientious about it. I don’t want to be the wrong guy playing a role and I have been as couple of times, but if it’s only one in 10 or one in 15, that’s probably a good average.

BROWN: Is there a specific role, or a type of role, that you’ve never had the opportunity to play but would like to?

GILLEN: I’ve been trying to play some warmer characters in the recent times. I have been doing it, too, but they’re in lesser-known dramas. There’s a film called Treacle Jr. that I did a few years ago, which was my second collaboration with the director Jamie Thraves, and we’ve since done another thing together. He pointed out that I’ve been playing a lot of villains or cold characters, and he’d first seen me doing comedy at the Bush Theatre, and maybe we should be exploring that. [Our new] project together is called Pickups and it’s funny, but also pretty dark.

BROWN: Do you consider Littlefinger a villain?

GILLEN: No. I know I look like one. [laughs]

BROWN: Has your perception of him changed over the series?

GILLEN: Not really, in that from the outset, I’ve tried to make it believable and make him likeable and make people want to be on his side. It’s that way in the books too; it makes sense that a character like that wouldn’t get to where he is, or do things he does, without gaining people’s trust and being charming and non-threatening.

BROWN: For me, his interactions with Sansa are what confirmed his character—that he is sort of a terrible person.

GILLEN: You’ve only thought he was a terrible person since then?

BROWN: Yes.

GILLEN: I thought I was getting more sympathetic. [laughs] There was one thing there on the Sansa track where I put her in a situation with Ramsay Bolton, but that was a mistake.

BROWN: Do you have a betting pool for who’s going to win the Iron Throne?

GILLEN: I don’t care. [laughs]

BROWN: Fair enough. It would be interesting if it were Little Finger.

GILLEN: Yeah, but it would be kind of obvious as well at this point.

GAME OF THRONES RETURNS SUNDAY, JULY 16, 2017, ON HBO.