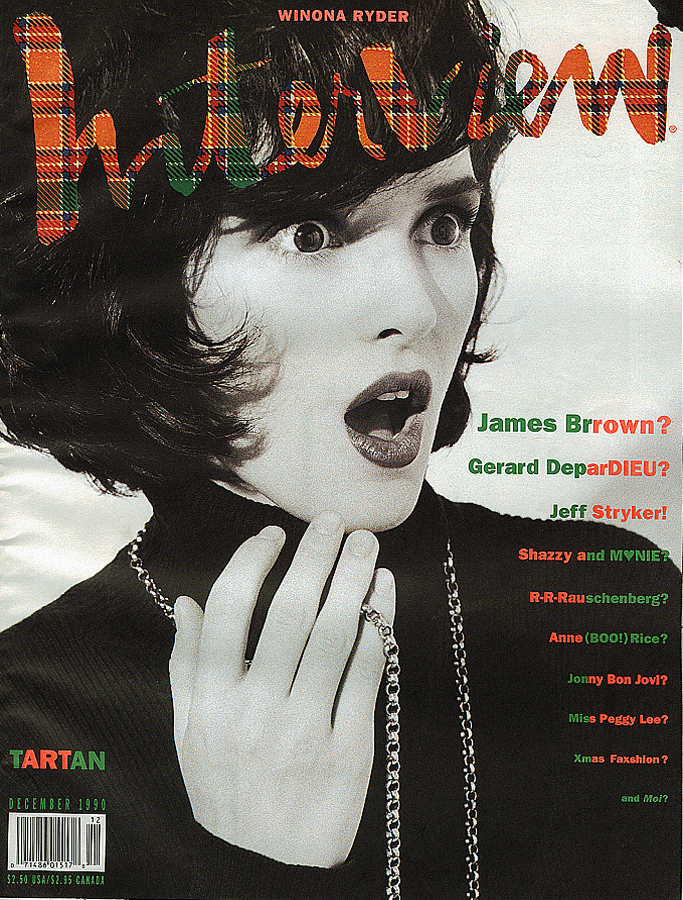

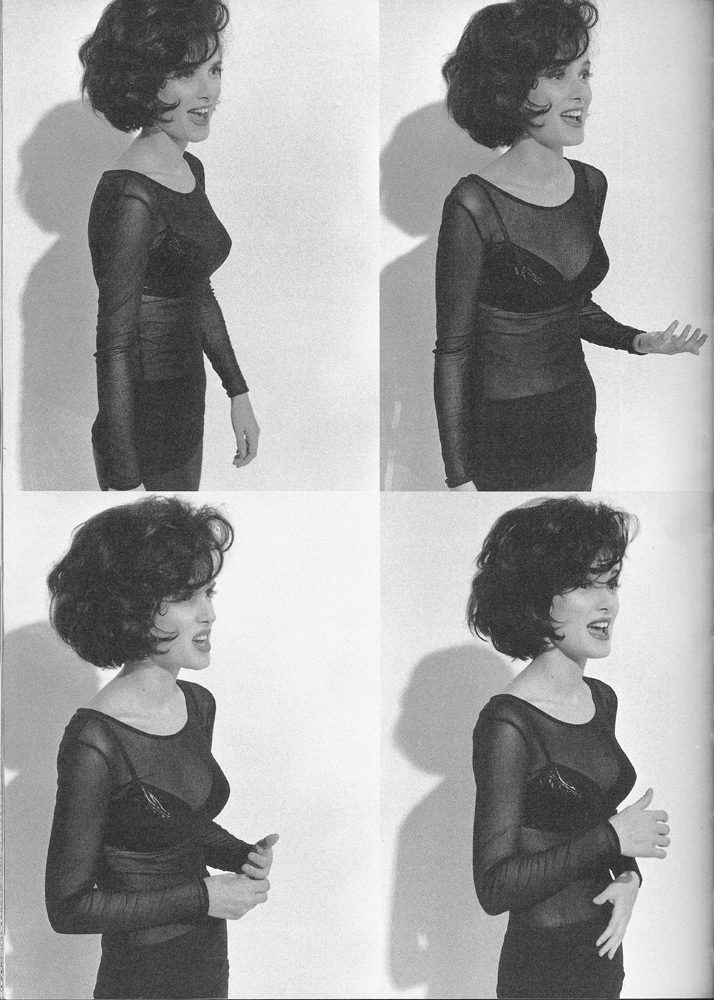

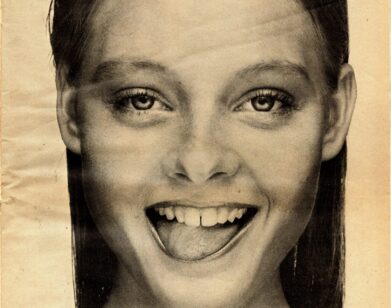

PARADIS ICONS

A Taste of Paradis: Winona Ryder, in Conversation with Jeff Giles

———

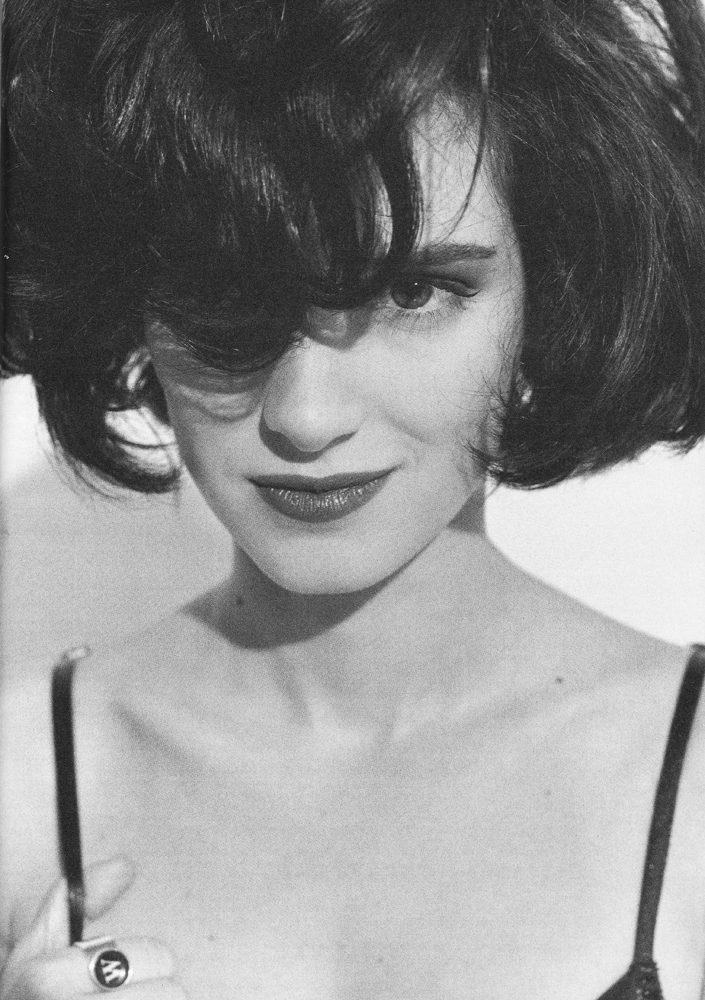

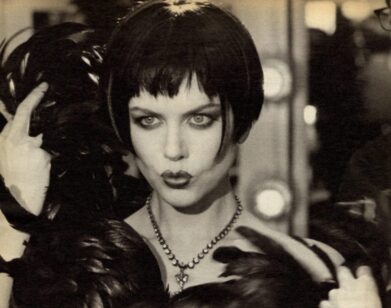

Nobody rolls her eyes like Winona Ryder does. Or knits her brow. In her career so far, the 19-year-old actress has been a teenager’s teenager—playing left-of-left-field characters who are constantly dying of boredom and humiliation. Often it’s a single campy touch that sends Ryder into orbit. In Beetlejuice, in which she played a death-obsessed schoolgirl who routinely goes to the dinner table in full mourning dress, it was a black hat roughly the size of a satellite dish. In Heathers, it was the monocle she wore while scribbling fiercely in her diary. In the video for Mojo Nixon’s song “Debbie Gibson Is Pregnant with My Two-Headed Lovechild,” Ryder’s sublime romping as the teen pop singer belongs on any list of her memorable performances—it was as simple as a blond wig. All this is not to say Ryder hasn’t figured in a few throwaway films, namely 1969 and Great Balls of Fire. Still, she stayed afloat even as those pictures slid into the sea. She’s a world-class eccentric, and she has played teenagers as many of them really are: sweet, smart, and geeky.

In person, Winona Ryder is all of those things. The actress, who is Timothy Leary’s goddaughter and who lives in downtown New York, has come to a Chelsea restaurant to discuss her winter hat trick: Mermaids, Edward Scissorhands (blond again), and Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael. After ordering a Shirley Temple and a side of fries, Ryder begins with her part as Cher’s exasperated daughter in Mermaids. It is the funniest, most challenging role she’s had to date, and she wears a great pair of boots.

JEFF GILES: What initially struck you about your part in Mermaids?

WINONA RYDER: What I related to about Charlotte is that she’s inconsistent. One day she’ll be obsessed with Catholicism, but the next day she’ll be obsessed with Joe the gardener. And the next day she’ll want to be an American Indian. I had really been going through stuff like that. I would think, I’m going crazy! I don’t know what I want! I don’t know who I am!

GILES: What were you obsessed with?

RYDER: I loved To Kill a Mockingbird, so I’d get really obsessed with that era, that place, that mood. And then the next day I’d be into a certain band.

GILES: What bands do you like?

RYDER: Well, my favorite band of all time is the Replacements. Paul Westerberg is like—I swear, I get teary-eyed when I think about him. If I were to have a hero or a personal god, it would be him. Actually, a song the Replacements sing really inspired my performance in Mermaids.

GILES: What song?

RYDER: “Sixteen Blue.”

GILES: That’s a great song. “Your age is the hardest age / Everything drags and drags.”

RYDER: To me, the song is about inconsistency. It’s about thinking you are crazy—that’s how you feel when you’re sixteen. There’s this incredible guilt that Charlotte carries around with her: “I don’t know who I am. If I want to be a nun, why am I horny?” That was another thing that was really interesting to me about the role—the religion part of it. I’m an atheist.

GILES: Was religion a part of your upbringing?

RYDER: No. My father believes that Western religions are death cults, which I agree with.

GILES: That’s a severe idea to grow up with.

RYDER: He didn’t inflict it on me. I was raised to believe that religion is a beautiful thing, but it’s fiction. I’ve read the Bible. I think the Bible’s a great book, but it’s a novel. It’s beautifully written and la-di-da, but people really took it the wrong way. My parents were great in the sense that they treated me like a human being when I was growing up. They showed me how beautiful things can be and how ugly they can be.

GILES: Is it true you grew up in a commune?

RYDER: First of all, I should tell you that everything that’s been written about that has been wrong. I grew up in San Francisco. My parents were not hippies; they were writers. They were very active politically, but on the intellectual side, not on the “taking drugs in a field and listening to the Grateful Dead” side. I’m glad I’ve got a chance to say this, because it’s been misconstrued. How I was raised was, there were no rules—nothing like that. If I wanted to take a drug because I was in school and everybody was doing it, I could go to my parents and say, “I really want to try this.” And they’d say, “If you do this, O.K., but this is what can happen to you…” They’d say, “Don’t get it in the streets, because it could be really bad and make you freak out. Don’t take it in a crowded place, because you’ll panic.”

GILES: That’s good, practical advice, actually.

RYDER: They would tell me the effect of the drug, and I’d end up not wanting to do it. In previous interviews, people have really made it sound like my parents were giving me drugs.

GILES: But actually they were just taking the mystery away.

RYDER: Yeah, exactly.

GILES: This sounds like an argument for legalizing drugs.

RYDER: I definitely believe in legalizing drugs. It does take the mystery away. It takes the money away, so suddenly there are no drug wars. If you’re a junkie, you can get help easier. [pauses] I’ve never said all that before. I’ll probably get a million letters.

GILES: There’s an obvious question I could ask you at this point—

RYDER: I’m not a drug user myself. I’m too little to take drugs—my body can’t take it.

GILES: Where did the “commune” theory about your family come from?

RYDER: We shared 300 acres of land with other families, but it wasn’t a commune. We had our own house and we went to school and it was normal. I practically grew up in the ’60s because my house was like that, and I’ve read a lot of stuff from then. But what’s great is my parents aren’t stuck in the ’60s. My dad is so into the culture of today. He was taking me to concerts ever since I was a kid, and it wasn’t Country Joe and the Fish, but the Dead Kennedys, Bow Wow Wow, the Pretenders. I love my parents a lot, and I think they made good choices.

GILES: In how they raised you?

RYDER: Yeah. There’s this line in Heathers when my character is, like, freaking out and saying, “All we want is to be treated like human beings, and not to be patronized, or experimented on like guinea pigs.”

GILES: People really responded to Heathers.

RYDER: I got a lot of letters.

GILES: What were they like?

RYDER: Most were great. I got a lot saying I’d helped people graduate from high school.

GILES: How did you do that?

RYDER: I have no idea.

GILES: What about the letters that weren’t so great?

RYDER: They thought the film was making a joke about teen suicide. One of my friends committed suicide when I was in high school, and it’s the most tragic thing anybody can go through. But what we were making a joke at was that society makes it so romantic. I mean, you watch these TV movies about teen suicide and you want to jump in front of a bus. Because your biggest fantasy is your own funeral. No one will admit to it, but it’s true. Everyone’s gonna cry and you’re gonna get a two-page spread in the yearbook. That’s what happened to my friend. People made fun of her. People were horrible to her. But she kills herself and everybody’s her best friend. Everybody talks about how wonderful and beautiful and great and artistic she was. And they gave her a spread in the yearbook, just like in Heathers. So when I read the script I understood that it was showing what society does to teenagers, and how it patronizes them.

GILES: Most movies patronize teenagers, too.

RYDER: It would be great if teenagers could make movies. It’s sad how some writers think they can write about stuff they don’t understand.

GILES: Dan Waters, who wrote Heathers, is an exception to that.

RYDER: He created a whole language. Not just slang—a language. In my first meeting, I said, “I will do this movie for no money and I will do it even if it never comes out. I just want to say these words.” It’s still a script I read a lot, and it’s still a movie I watch a lot. My character, Veronica—she’s my idol.

GILES: What about your character in Beetlejuice? It seemed like that person was a caricature of you—the California girl who can’t stand the sun.

RYDER: It was fun to play that up. My friends just love that movie because I’m making fun of myself in it. Most of the clothes I wore were my own.

GILES: You were recently in one of those “America’s Ten Most Beautiful Women” issues of Harper’s Bazaar. I really loved what you said, because I think you gave some of the most unhelpful beauty tips ever offered to American women. One was, “There are times when I do like to brush my hair.”

RYDER: I didn’t know what to say. If anyone followed my advice, I don’t know what they’d look like. I’m not a big one on—I don’t know what to call it—getting all glamorous. I don’t really worry about my looks, and I don’t worry about getting old. Exterior beauty doesn’t mean a lot to me. I mean, sure I like to look nice—sometimes. [pauses] This is going to contradict all the pictures with the interview, because I’m very glammed out. I’m a total hypocrite, because I did it for Harper’s Bazaar too. They asked me, and I said, “Sure! Ten most beautiful women? Me? O.K., whatever turns you on.”

GILES: In Edward Scissorhands, your character, Kim, learns that appearances can be deceptive when Edward, played by Johnny Depp, comes to stay with your family.

RYDER: Yeah, and we end up falling in love. It was a really difficult part because it was a kind of girl I’ve seen but never known. She sort of starts out like the girls who used to throw Cheetos at me in high school.

GILES: Somebody threw Cheetos at you?

RYDER: Cheerleader types. Not to put down cheerleaders.

GILES: So Kim starts out as a “Heather.”

RYDER: Exactly. She’s a Heather. But then she “finds” herself, realizes what’s important, and falls in love. It’s very gradual. She hates Edward at first and is terrified of him, but he shows her “beauty.”

GILES: It couldn’t have been a chore to work with Johnny Depp. But your relationship with him has been the source of a lot of speculation in the media.

RYDER: What we have .. Nothing I say will really be right. I will say that he’s an amazing human whom I have an enormous amount of respect for and very deep feelings for. It’s not a possessive, weird little Hollywood promenade.

GILES: Does all the publicity put pressure on the relationship?

RYDER: It could, but what’s important is our life. That stuff’s secondary—it’s not even secondary. It’s in, like, eighteenth place.

GILES: People worry about you. They think you’re too young to be engaged.

RYDER: I’m not getting married. It’s nice that people worry about me, but they don’t know me and they don’t know what we have. And it’s not what they’ve said it has been. It’s a friendship. It’s a relationship, but we’re not married, and we’re not getting married. We’re just hanging out. We both have our own lives.

GILES: In general, do you hang out only with other actors?

RYDER: I’m not in that clique. To me, it gets boring after a while. There are other things, out there. The actors that I do know are people who I think have souls, you know?

GILES: I read something interesting that you said about acting. You said you don’t play comedy as comedy.

RYDER: With Heathers, and with every comedy I’ve ever done, I haven’t played them for jokes. I take it very seriously, and I think that’s what makes it funny. It isn’t funny when you, like, wait for canned laughter or you wait for the punch line. There’s a scene in Great Balls of Fire when I get married. Myra was twelve at the time, and she’d been kidnapped by this guy who was threatening her into marrying him. To me, the scene was very sad and confusing, and I tried to play it that way. But then in the screenings, everybody laughed.

GILES: You had to pull out of The Godfather, Part III a while back. Did that experience teach you anything about acting?

RYDER: Yeah, it taught me that I have to slow down. I had done three movies back-to-back, with literally no time in between. Toward the end of Mermaids I got sick with a respiratory infection, because it was freezing in Boston and I had to wear little dresses. I was really sick, and I couldn’t get better because I was so cold all the time. And then I had to leave to do The Godfather the day after I finished.

GILES: You flew to Italy.

RYDER: I never should have flown. The doctor said I could have gone deaf. So I got to Rome and I was in bed. The doctor came over and said, “You can’t work. You’ve got to rest.” Of course, that’s not the way everybody made it sound. They made it sound like I freaked out and ran. I regret screwing people up, but I would have been a wet noodle. My acting probably would have been panned. How do you act when you don’t have anything left? One thing you have to have when you act is energy.

GILES: How do you relax nowadays?

RYDER: I read a lot. I watch movies, I listen to music, and I write.

GILES: What do you write?

RYDER: I keep a journal. It’s not a corny journal. It’s not like, “Today, I had some Honey Nut Cheerios and then I went for a walk.” It’s train-of-thought-type stuff. I also write short stories, and I like to travel. Sometimes, get up and go to Texas, or something.

GILES: Texas?

RYDER: I love Texas. Even if I am a little bit famous or a little bit popular… You go to places where you’re not and just live like everybody else lives. I’m not crazy about this country in terms of the shape it’s in, but I do think there are lots of great pieces to go to. I think I should take advantage of it while this country still exists.

GILES: Do you worry that the country’s not going to exist?

RYDER: I don’t know how much longer the environment is going to exist. I sort of strongly believe that we’re in danger. Not to go off on that.

GILES: You can go off on that if you want.

RYDER: I don’t want to preach, and I don’t want to tell people what to do.

GILES: Actors tend to preach in interviews.

RYDER: They go off on all these world issues. I’m not saying that all of them are jumping on the bandwagon, but I think they should back up what they say. I really believe that, because I think a lot of them are full of shit. And if you’re gonna talk about the environment or make a big deal about South Africa or Northern Ireland, you should know what you’re talking about.

GILES: Let’s talk about your future as an actress. Because you’re young, you’ve always been given parts in which you “grow up.”

RYDER: Yeah, I must have come of age about 150 times.

GILES: And you’ve lost your virginity three times that I can remember. Is all this starting to get frustrating?

RYDER: Well, the thing is, I’m not going to do it anymore. Basically, you come of age all the time. In every part you’re coming of age, even if you’re an adult. But I don’t have anything left to offer in the teen angst area, because I’ve done it every way I know how.

GILES: Are you worried about getting “older” parts?

RYDER: I’m too young to play lawyers. But I’ve been really lucky because I never got labeled. I never did the John Hughes thing. I did adult movies. I’m not bragging or anything, but I think that I’ve chosen really good roles. I’ve played different people and showed that I have a little bit of range. If something brilliant comes along but I really feel like it’s too old for me—that I’m not gonna have the experience it takes—I’m not gonna do it. Even if it’s “a big mistake for my career” or whatever I’m threatened with that week.

GILES: Do you have agents twisting your arm?

RYDER: I used to. Everything was strategy. “In order to win your Academy Award at 23, you have to…” You don’t do it that way. I mean, you do a movie if it’s good and if you want to do it. It doesn’t matter if it’s small or big or expensive or cheap. If you want to say the words, you’re gonna say them. You can’t strategize.

GILES: But most actors try to.

RYDER: Actors do these really gross, gun-’em-down movies, and I always wonder why. They’re not good movies. And it’s like, “Why are you doing them? Aren’t you rich enough?” Maybe make mistakes or make bad movies, but I’ll never consciously do that—and I know that like I know I love my mom. To me that would be death, and nothing’s worth that. Nothing. I’ve felt that before, and I’ll never do that to myself again. My greatest feeling—this is probably gonna sound like bullshit—

GILES: Try it.

RYDER: A lot of my fans come from Boston. Heathers, for some reason, was huge there—I didn’t know it until I went there. So I was, like, walking down the street and this group of people came up to me. They were in college and they were really smart. They weren’t critics, they were my peers. And they go, “Everybody we’ve ever liked has sold out, and maybe you will too someday, but we don’t think so.”