The Consciousness Raising Artist

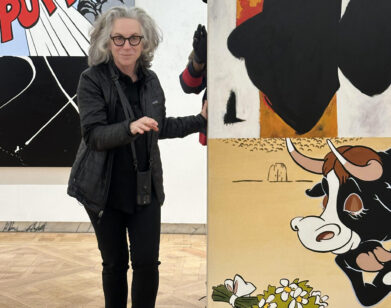

ZOË BUCKMAN IN NEW YORK, NOVEMBER 2016. PHOTOS: VICTORIA STEVENS. GROOMING: AZRA RED FOR HONEY ARTISTS.

“I had someone gag when they looked at the placenta,” says Zoë Buckman when we meet in her downtown Manhattan studio. It’s the week following the presidential election, and the 31-year-old artist’s work, and this reaction, feel unsettlingly relevant; so-called “women’s issues” are at the fore, and have been on Buckman’s mind for quite some time. She’s speaking about a work from her 2013 series Present Life, which features her own placenta, preserved and positioned as though floating in recessed marble. “I actually thought that was funny,” she recalls of the guttural reaction. “I was like, ‘Yes, my art is visceral!'”

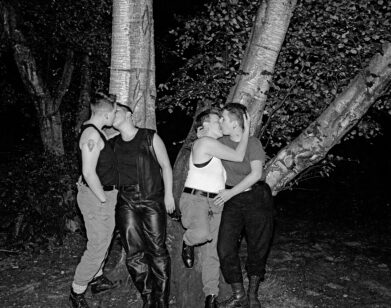

That visceral quality translates across Buckman’s use of media; she works in photography, neon, installation, sculpture, and sound. And she addresses fraught topics: giving birth, eventual death; the attack on women’s healthcare and Planned Parenthood; the duality in hip-hop’s language; existing within a patriarchy. None of this is to say that Buckman’s work is “art about women” or “art for women.” For her, it’s about consciousness—specifically, raising it—whether that’s through shock, confusion, laughter, silence (or even that gag).

At the start of the New Year, Buckman will reveal We Hold These Truths To Be Self-Evident, a mural (made in collaboration with Natalie Frank) at New York Live Arts; its text material is taken from statements made about women by elected officials. In February, she’ll also present a new body of work at Project for Empty Space in New Jersey; titled Let Her Rave, it began in reaction to a line from John Keats’ “Ode on Melancholy:” “Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows / Imprison her soft hand, and let her rave.” While Keats is Buckman’s favorite poet, and was even read at her wedding, this line remains irksome. “It struck me as amazing that women need to A. be given permission to feel the way they feel and B. be told that we must be physically restrained by a male in order to have our little hysterical moment,” she explains. The resultant series of used wedding dresses, meticulously cut and sewed onto boxing gloves, are hung in clusters from heavy metal chains—suggesting the weight, strength, and delicacy of marriage and its impact on womanhood.

HALEY WEISS: You have such a broad practice. What was your first medium?

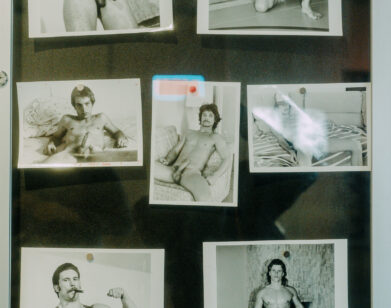

ZOË BUCKMAN: I started out in photography, and I went to the International Center of Photography [and graduated in 2009]. My first show was more traditional photography; I was staging images of women, shooting them, and I was etching snippets of text into the glass of the photo frame. So even at school, I was already trying to find a way to branch away from the flat image. I don’t think I ever really felt comfortable with photography as my sole medium. But it wasn’t really until I became a mother—I really credit that to opening me up artistically, I think because it was such an empowering birth for me—it gave me the confidence to explore different modes of expression. So then I started using embroidery, which I had learned when I was 15 at school, and I started working with neon because I felt that as a photographer, we use light and neon is light, and it felt more pure. Then I just felt like I didn’t want to stop there. Now there are a bunch of different mediums in tandem in my practice, but each mode of expression for me is the right way to tell that particular story. So it’s not that I’m just fucking around because I can’t commit. It’s more that this story needs to be told through light; this story needs to be told by cold, harsh metal; this needs to be a video. And each discipline is very specific to the experience that I’m trying to create with that particular piece.

WEISS: How did you start working with the vintage lingerie in Every Curve?

BUCKMAN: I was thinking about how I wanted to make this work, and it was really important to me that I embarked on a body of work that explored my personal grappling with the hip-hop lover inside of me and the feminist inside of me, and how those two voices were at odds. Particularly after I had a daughter, it became more urgent for me to make this work. I was thinking about femininity and an immersive experience that would envelop the viewer. I started to think about vintage lingerie, and how that could tell a story about the history of women, and then I thought, “Well, how am I going to use this language—which is really important to me, which is genius language, on par with Shakespeare as far as I’m concerned—how am I going to get that onto these really delicate pieces?” So I thought I could spray-paint, I could stencil and cut out the lyrics, or I could sharpie them, and all of those felt too violent—and too obvious. And I was worried that people would see it as merely a criticism of hip-hop, and it would look like hip-hop is this violent thing that imposes itself on fragility, which is not personally how I feel. So for me, the medium of embroidery was perfect because it also gives this element of an artist spending a really fucking long time doing something, and when you’re spending a really fucking long time doing something, you’re paying tribute to that language. Cutting something, spray-painting, and sharpie-ing, it’s a bit disrespectful I felt, whereas embroidery felt more memorializing to these two men [Biggie and Tupac] who had obviously passed away as well. Then I was super drawn to embroidery because of its history within artistic practice, because it’s a feminist mode of expression largely.

WEISS: It’s interesting because if you’re going to be critical and say, “These lyrics are degrading,” or, “They’re violent and intense,” some of the garments are too. They’re structured and trying to make you look a certain way; I think that criticism is just as valid.

BUCKMAN: Exactly. And that’s why I tried with the embroidery to really highlight the areas that were incredibly restricting, so if a bodysuit from the ’60s had little metal hooks at the crotch, I would loop thread through that and have it dangling down, so it looks almost like stitches. Or I would sew around those harsh contour lines or the boning, so that we’re constantly being reminded that, “Holy shit, it’s hard being women. It was hard then; it’s hard now.”

WEISS: Was the first work you made after you became a mother the placenta piece?

BUCKMAN: Yes—that was from a show called “Present Life,” and the placenta was the first piece I made for that. Then it became an exhibition about time and about how everything living at some point dies, and how can we through art preserve that moment. Becoming a mother really put me in touch with not just my mortality but also my baby’s mortality. You spent nine months working on this thing, and it’s finally there, and the first thing you think about is, “I don’t want my child to die.” And I did, at least, have a real desire to try and freeze-frame her.

I really didn’t know anything about the placenta. I never thought about it, and I certainly didn’t think it was anything I was going to turn into art. But after I gave birth, the midwife examined it, and she told me that upon looking at it, she could tell that it had actually started to deplete. I thought, “Oh, that’s nice,” and then she explained to me the severity of that, and that everything was fine because I had gotten into labor early and it was all good, but that if I hadn’t gone into labor early, it would have reached the end of its journey and detached from my body, and I would have had a still birth, which is every pregnant woman’s nightmare … That really shook me, and put me on this path of wanting to preserve that fleeting moment—when something that’s fruitful starts to wither.

WEISS: When did you start calling yourself an artist?

BUCKMAN: I found it really, really difficult, and I think this is maybe part of being a female artist as well in that were not as predisposed to owning our own space. It wasn’t until I became a mother that I started to refer to myself as an artist as opposed to a fine art photographer. And the first couple of times I said it out loud in a social setting, when someone asked me what I did, it sort of got stuck in my throat and squeaked out, because I had never said those words and I felt really… It’s just such a loaded word, and it felt like such a loaded thing to say, and now, over time, I’m totally comfortable with saying, “Yes, I’m an artist. How are you? What do you do?” [laughs]

WEISS: We were talking before about how there’s more effort required as a woman to be taken seriously. Do you feel that sexism in the art world—where you come up against people not taking you seriously because you’re a woman?

BUCKMAN: I think A, it’s harder to be taken seriously as a woman. B, if you happen to be a woman who goes against the stereotypical view of what an artist is and should be, it’s even more challenging. I’m atypical in my personal life, my situation is not that of the average struggling artist, and so I feel like I have to work even harder to prove myself and let the work speak for itself. At the same time, I’m not prepared to hide who I truly am. I’m not ashamed of my amazing personal life—my marriage, my child, how blessed I am to have a studio like this—I’m not going to let myself hide from it, but I have to make sure that the work is constantly at its best. And I’ll just have to prove all of those fuckers wrong.

WEISS: Do you come from a creative family?

BUCKMAN: Yes, I do. I come from a really creative family; both on my mother and father’s side there were a lot of bohemian theater people. My mum was a drama coach at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and a writer and a director, and my dad’s side of the family, they were all directors, actors, and acting coaches as well. So I grew up to really appreciate language and literature and with a real sense of play and expression. I feel like my art, particularly the more installation-based pieces, there’s a real theater element, and it feels kind of performative. I just personally never want to act; I’m not at all interested in that. But then look at who I married, I went and married an actor [David Schwimmer], so it’s like you run away from something but yet you bring it into your world. [laughs]

WEISS: It’s odd how works like these leading up to the election were part of this empowerment, but it almost becomes even more empowering afterwards to say, “This is so necessary.” This election has been…

BUCKMAN: [sighs] I’m still in shock. It’s in layers, isn’t it? It’s waves of bewilderment, shock, outrage, depression, apathy. Sometimes you’re just like, “Well, fuck it. Why bother?” And then we all have our moments when we’re catapulted into action mode. … I think we’re all just trying to find our way with this.

WEISS: Do you have renewed energy toward your practice?

BUCKMAN: I feel like I’m starting to get the fight back. I think I’ve still got one foot in the grieving stage, and I’ve got one foot in the acting stage. Hopefully in time I’ll just be ready to go all out.

FOR MORE ON ZOË BUCKMAN, VISIT HER WEBSITE.

For more from our “Faces of 2017” portfolio, click here.