Meet Yukino, the Photographer Who Leaves Her Art to be Found

The artist and photographer Yukino has been making short runs of periodicals for some time. No theme holds them together; she gives no explanation to her content. Invariably, they’re printed on cheap paper, stapled and held by paper clips or folded inside anonymous manilla envelopes. Once made, the publications are left without fanfare in supermarkets or train stations, snuck inside magazine stores or libraries. “Where they’re left isn’t important,” she says. “I don’t care what happens to them afterwards. All I want to do is make them. After that, I’m done.”

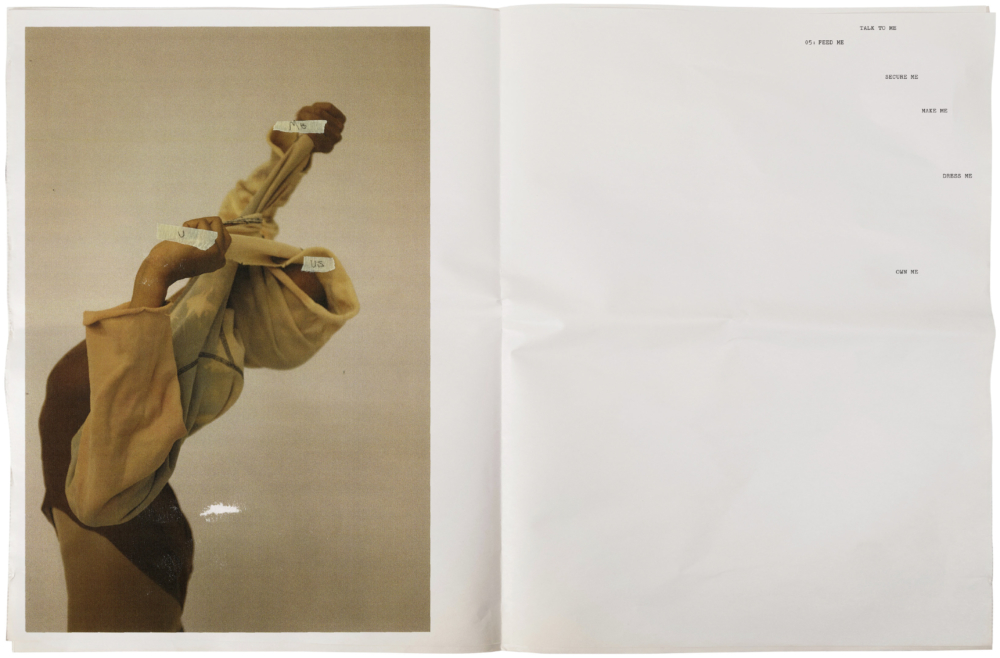

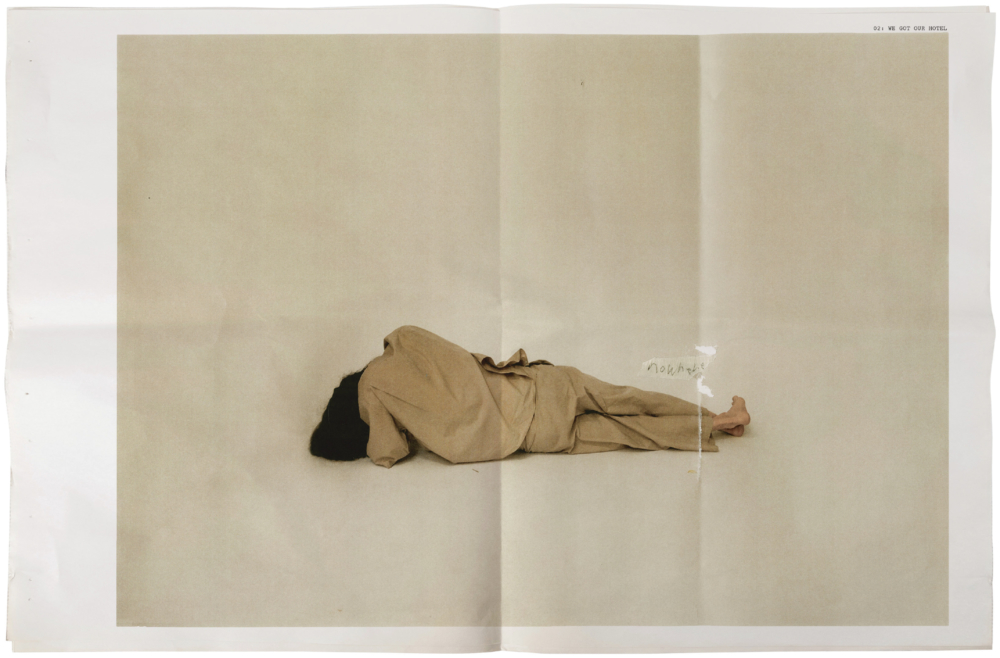

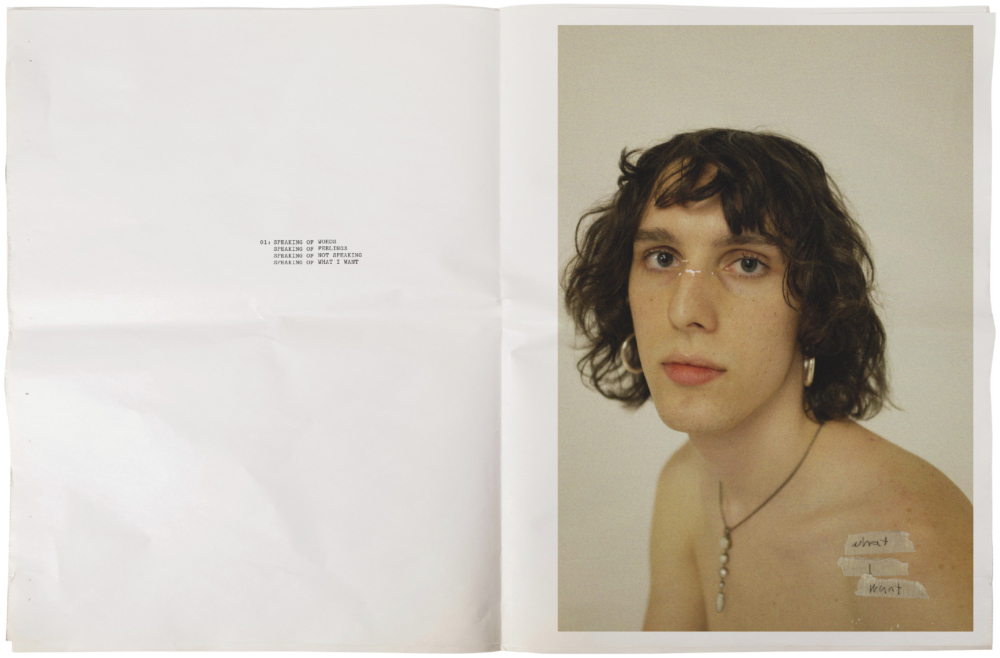

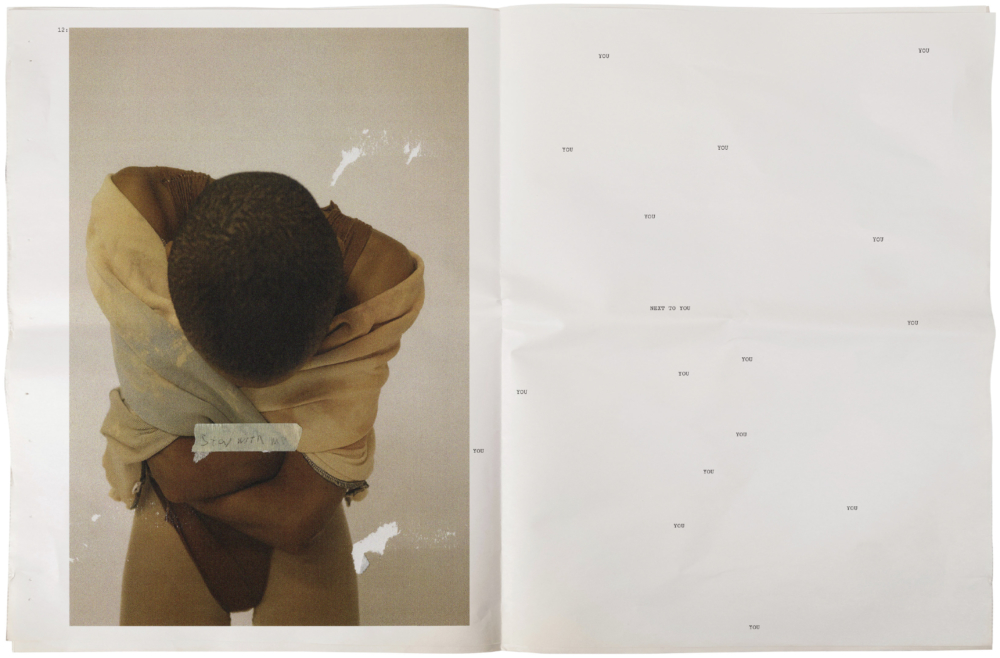

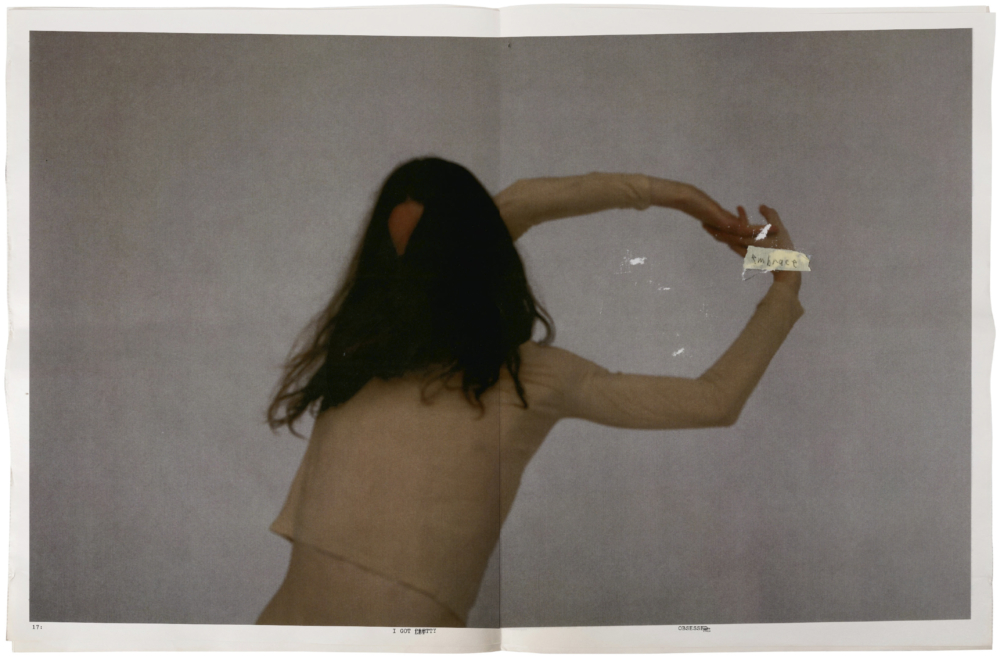

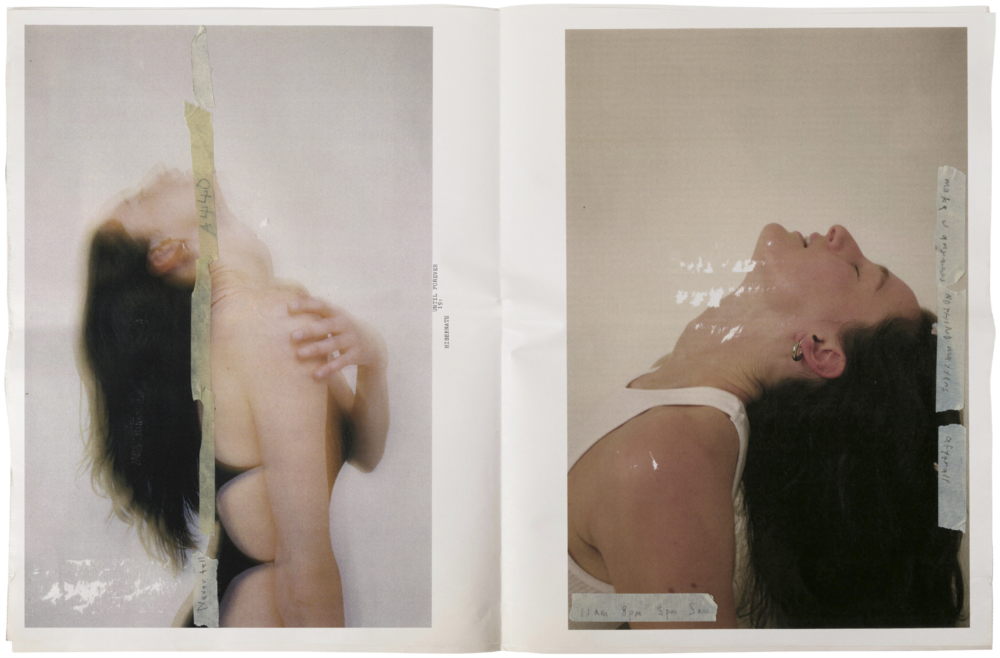

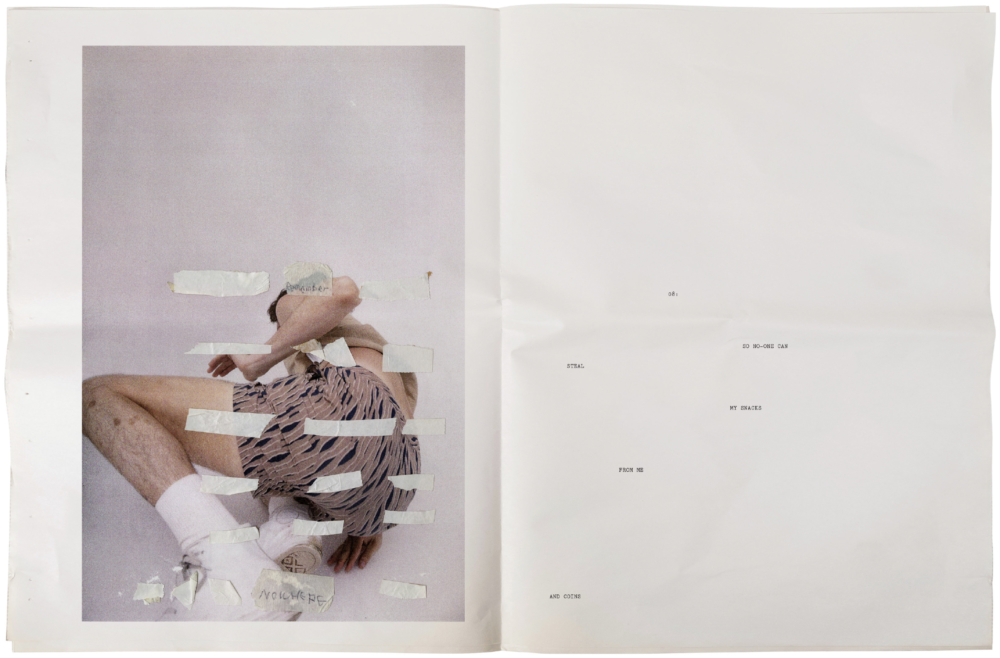

Her latest work, titled “Did You Even Realize I Drew Your Eyes,” is collection of photographs of bodies twisting and contorted alongside broken-up text that’s been scattered against the pages. The images have been degraded and ripped, often layered with tiny torn pieces of artist tape. The effect is dreamy and dislocated, yet intimate and fragile—the images and their meaning rendered almost translucent on the thin newsprint they have been printed on. Though the pieces remain a blur, even to the artist herself, here are some things she said about them.

RICHARD TURLEY: What attracted you to the form of a newspaper?

YUKINO: I like the sense of anonymity and its openness to being owned, destroyed, and crumpled. I’m also drawn to the vulnerability of its physical form. Ink being smudged and pictures fading overtime, the newspaper itself falling apart. For me, I think it was experience similar to how we cope with our childhood memory. Fragments of memories, unknown sequences of moments that we catalog and rework, glimpse at and try and understand, reorder, but that ultimately fall apart. I also like the cheapness. The fragility. It feels like a humble medium to think in. Generous somehow to the person holding the piece, and also to the person in the photo you’re staring at.

TURLEY: Is there a story or a narrative that works through the piece?

YUKINO: It could have a narrative but it may be more like an improvised dance or dialogues shared between words and pictures throwing up new meanings as they collide. Nothing is really meant to stay—just this process and experience of that moment archived on paper. Even though the piece is experienced through paging through a newspaper, it inevitably leans on that traditional sequencing framework you have with a publication where one page relates to the next, but that was not something I was interested in. Nor do I think these pictures stand on their own like pieces of art in a gallery or as they might do if situated in a traditional artist publication. They are linked but they’re not. I want to explore the bit that’s between those two positions, and develop an uncertainty between how the pictures relate to each other.

TURLEY: How much of a role did the people photographed play in the creative process? Can you describe a little of the way you worked with them?

YUKINO: I really don’t know how to explain this properly. The photo sessions were and still remain a blur to me. I think I was observing my memory through the perspective of other people, understanding my own story through movements that their bodies made. I wanted to capture the moment and let myself be controlled by the forces acting upon all those inside the room. Almost as soon as I left the room after shooting the pictures, my body forgot what had happened. The pictures were shot mostly on film, so getting the pictures back involved seeing what happened for the very first time. It was that process I tried to retain all the way through making the piece. That element of a first impression, of a surface-level relationship. I didn’t want to get closer to the pictures than that. Or try to understand or try and create a narrative of what they are about, what they are now or even what happened. So it follows that every adjustment I made to the piece after that was to try and step further and further away from it, to remove myself almost entirely.

TURLEY: How did you approach the clothing choices?

YUKINO: There wasn’t really an approach but I think I wanted to focus on what’s going on inside the heads of the people I shot, so their appearance and how they dressed didn’t matter much. But it was nice to use the clothes more as distracting elements, creating a tension between the person and their movements. Maybe the clothes end up functioning almost like extensions of their thoughts, like a fog. Maybe I’m thinking about some of Olafur Eliasson’s installations that let you really focus on the subject and challenge what you are supposed to be seeing.

TURLEY: Can you talk a little about the text, what it means and how you applied it the images.

YUKINO: In some ways the text is very personal. In other ways, it’s totally vague and meaningless. I like that tension between it—how it oscillates between revealing too much and saying nothing at all. The sentences themselves doesn’t need to be explained or decoded. In some ways, it is me hiding in public. Expressing myself by saying nothing. In terms with how they’re applied to the pages, the juxtaposition of words and images has more to do with the shapes the words make than what the words say and how they relate specifically to the image that they are attempting to modify. What I want you to do is feel, not understand.

TURLEY: How have you been coping with the lockdown? Where have you been based?

YUKINO: I recently moved to upstate New York. Where I live is pretty secluded, so a few days could easily go by where I don’t see anyone except for chipmunks and bees. I’m an introvert, so staying at home suits me well, but there are of course days when the world seems like an awful place. Lately, I’ve tried to look to nature and even channel some of John Cage’s thoughts from a book I recently read called A Mycological Foray, where he talks about society resembling the mushroom’s cycle of life, how destruction and decomposition of a system is necessary to its rebuilding and rebirth.