In conversation

Yoshitaka Amano and Neil Gaiman on the David Bowie Project They Never Finished

“It felt like the people who were seeing your art 25 years ago did not have the vocabulary to talk about what they were seeing,” the writer Neil Gaiman told Yoshitaka Amano when the two got together last month. Gaiman himself knows what it’s like to be a sort of outsider. “I was that weird guy doing that odd stuff out on the fringes,” he continued. Amano, the venerated Japanese illustrator, came to New York in 1997 with the dream of learning from pop artists like Andy Warhol, but he arrived too late—many of them were already dead. He’d meet Gaiman shortly after, collaborating on the comic book The Sandman: The Dream Hunters. Soon enough, both their careers were launched firmly into the mainstream: Gaiman’s novel, Coraline, became a smash-hit, and Amano’s commissioned illustrations for the Final Fantasy franchise have been the blueprint for video game illustrators ever since.

Now, Amano’s work is back in New York, decorating the Lomex Gallery with oil paintings of centaurs with washboard abs and willowy goddesses flanked by pythons, pastels, charcoal. It’s “pop art and fine art crashing into each other,” offered Gaiman when they spoke at Lomex, where Amano’s The Birth of Myth is on view through the end of the month, reflecting on mainstream popularity, the necessity of reinvention, and the David Bowie project they never finished.—ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS

———

YOSHITAKA AMANO: Let’s talk about how we met.

NEIL GAIMAN: It was all the fault of Jenny Lee who was at that time an assistant editor of Vertigo Comics, and she loved Mr. Amano’s work and she showed me some of his work and I loved it too and we asked him to do a poster for Sandman’s, whatever it was, 10th anniversary? He did a beautiful poster for us. I loved the poster and could not get what he had done out of my head. I loved the idea of taking the Sandman mythology and making a story set in Japan and we asked Mr. Amano if he would like to do a comic and he said, “No, he did not want to do a comic.” I thought, great, this is the best thing. I’m going to get to write an illustrated book.

AMANO: I don’t remember saying no.

GAIMAN: If you didn’t say no, then even better because I used the fact that you had said no to be allowed to do the book that we did, which was the paintings. What I remember was the joy, the enormous joy of meeting you, talking about what we would like to bring to the story. In my memory, we expected you to do 20 paintings, 15 paintings, something like that and instead you did 80.

AMANO: There’s so many that we couldn’t use.

GAIMAN: It was amazing because I think you had expected us to choose more and we basically managed to fit everything except maybe one or two in.

AMANO: Your writing, every time I read it, I get images, and that’s how we were able to incorporate so many. Maybe not enough. That was the magic of a good collaboration for me. The story would not exist without me going, “I want to write things that I want to see Mr. Amano draw and paint,” and everything in there, everything I wrote was images in my head and then I was sending it to you as I was writing it. I didn’t sit down, write the whole thing and then you did it. I’m writing it, I’m sending you a chapter at a time. You’re sending back drawings and images and I’m going, “Oh my gosh, this is better than I expected. Better than I imagined, better than I dreamed,” and I thought it was going to be good. Then I’m going in with renewed energy and passion.

AMANO: It was like doing a catch ball.

GAIMAN: Absolutely.

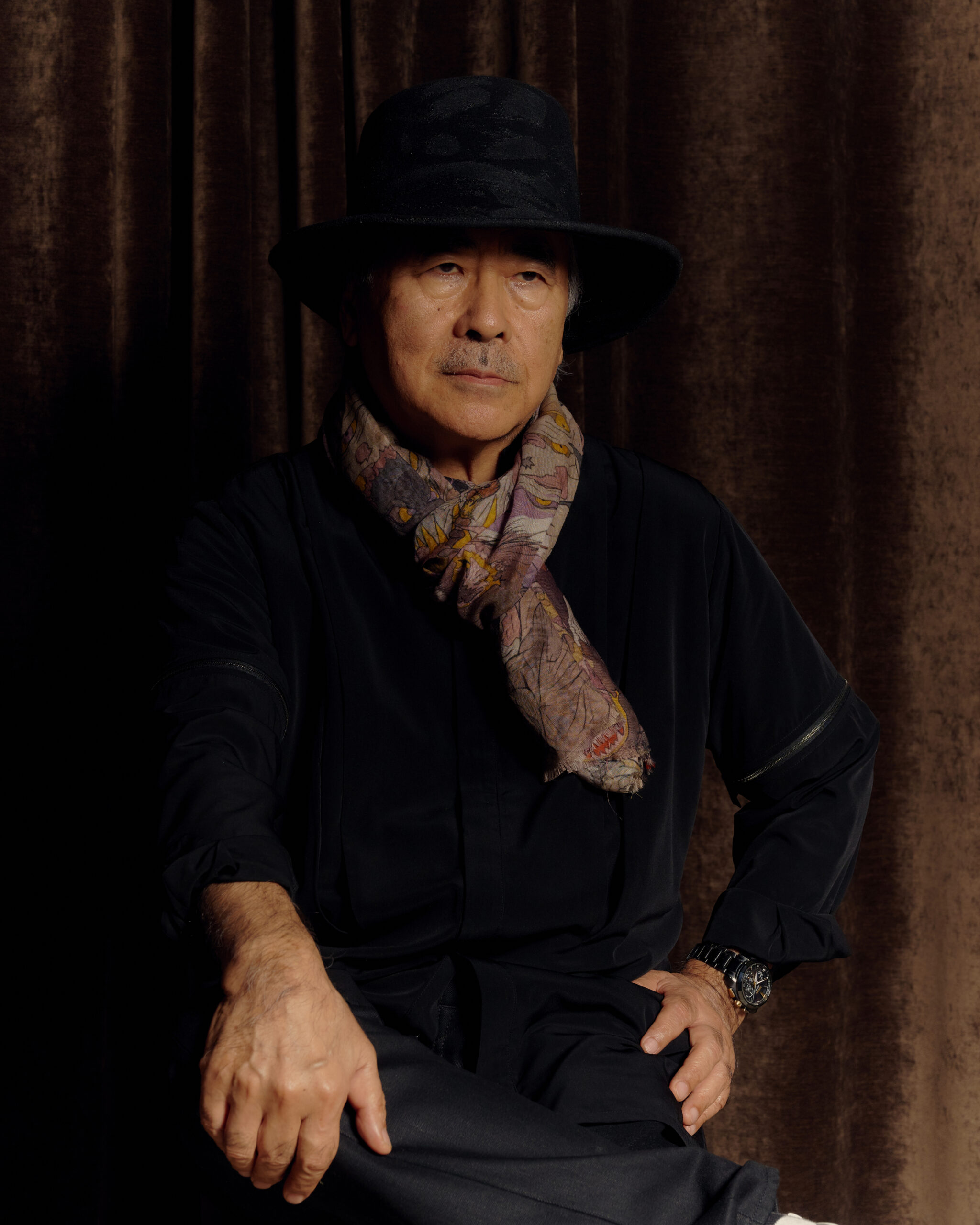

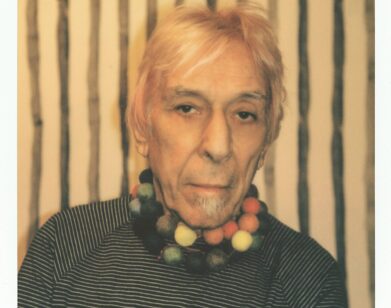

Neil Gaiman and Yoshitaka Amano at Lomex Gallery, where Amano’s “The Birth of Myth” is on view until October 28th.

AMANO: I was always like, “Oh, what’s going to happen in the next chapter? What’s going to happen?” I only just drew from your writing, just inspiration from your writing that you mentioned that it was more than your imagination. It was all you, your imaginative writing.

GAIMAN: It was, but it was also you. There was a point right at the beginning where I remember us talking about Daoist magic and about the onmyōji and the images of… What are they called? Those wonderful creatures that lurk in the dreamland and eat the dreams. They came directly from you. And nobody’s done anything like this since. I remember being terrified when I heard that it was going to be published in Japan in translation, and I just thought…

TRANSLATOR: Okay, Japan. Actually, Amano-san it was. He wasn’t really a hundred percent sure about Japanese stuff as well. He was kind of nervous. Over here, you could do whatever because even if you make stuff up, people wouldn’t understand, but in Japan, they can fact check you.

GAIMAN: That was what I was worried about. Fortunately, they bought it. I think we got away with it. Yes, I remember that it was the baku, the dream eaters. They were something I learned about from you right at the beginning. You were like, “Oh, if we’re doing Sandman, we have to include baku.” I’m like, “We will include baku.”

AMANO: My friend is named Baku as well, a very famous writer. He actually translated to Japanese and we were just really happy about that.

GAIMAN: Okay.

AKIKO MUKAE: Yeah, he’s amazing writer too.

GAIMAN: You look at the collaboration now, and I love the fact that there are the charcoal drawings, there are the paintings, there’s the ink, there’s the map, which is just sort of so delicate. Then, that which is so monstrous. The use of space in this one reminds me, there’s an Irish artist who died in the 1930s called Harry Clarke who did famous tales of mystery and the imagination, and was very famous for his stained-glass windows. He was one of the very few artists I know, apart from you, who would just go, “Yes, well, let this be blank space.” “Let this be dead space and put all of the information.” I just would take so much joy in the art coming in.

Speaker 7: I read somewhere that he was sending you photocopies.

GAIMAN: Yeah. The pictures would almost always be too big for the photocopies. The photocopies would arrive and they’d be sellotaped together, sort of two or three photocopies taped together for one big picture.

Speaker 7: Had you met him [Mr. Amano] in person prior to this?

GAIMAN: We did. We met a few times. He was living in New York at the time. I would come in to have meetings with DC Comics. We would meet and talk to Mr. Amano and his then American representative, and she would translate for us a lot and she would become my point person on getting stuff to and from him. For two people who do not speak the same language, we would have fabulous conversations that would go on for a long time.

AMANO: I get a lot of inspiration from your knowledge and ideas. Of course, this story is like a fantasy, but when you’re reading it, it’s kind of friendly or you can feel the love between the characters and I think from your script I felt that I could feel that you’re a friendly person, you have a lot of love in your writing.

GAIMAN: My favorite things, looking back on this, are tiny things. For example, we signed thousands of copies. Every now and again, Mr. Amano would find a copy for him to sign that I had failed to sign, so he would do my signature, which I would not be able to tell the ones that he had done my signature on. Nobody can do my signature, but he would just do it as lines and I had my signature. There’s something about that that it’s like, “Yes, you have the right. You can be me.”

AMANO: That’s the rhythm we have.

GAIMAN: It was. As far as I’m concerned, the people who got the Amano signature got a special book.

AMANO: Feels like western authors have to do so much work and they have to autograph so many books.

GAIMAN: One of the things that I responded to so much in Mr. Amano was the feeling that this was somebody for whom art was play, not work. For the way that children make art always excites me. The way that children tell stories always excites me. It’s never work. It’s always the joy of creation, and that for me and for so many people we work with, it’s work. Even for me sometimes it’s like, “Okay, I’ve got to write this. It’s work,” and I never felt that with you. I have always felt, okay, this is the thing to which I aspire, I’m going to make something up. For you it was, “look, I’m having fun!” I just made some lines that did not exist before. I made a person that did not exist before.

AMANO: Are you having fun? Is it work or are you having fun?

GAIMAN: A lot of the time it’s still fun.

AMANO: It’s fun.

GAIMAN: I’ve been making a lot of television over the last few years and writing the script still feels like fun. Everything else feels like work. Everything else you have to do to get from script to screen is work. I just started writing a book or I picked up a book that I wrote a thousand words of five years ago, six years ago and thought it’s time. I went for a walk in Central Park the other day with some friends and thought, wasn’t I going to do a story set here? I went and found my notebooks and there was the opening first three or four chapters of a children’s book all set in Central Park with frogs, and it’s all about frogs in the park and I thought, this is just fun, I should write this, I should finish it. My grandchildren will like it and I will enjoy it. I’m doing something now, which I haven’t done since Coraline. Instead of reading before bed, I will write and it means I may write 50 or 80 words and it’s not very much, it’s a third of a page. But if I do that every night before bed, I will have a book by the end of this, and it’s a book I’m just writing for fun. Nobody’s waiting for it. Nobody cares and it’s got frogs.

AMANO: In your everyday world you can draw inspiration from so many things like when you were walking in Central Park with your friend and then they inspire you to finish the book about the children and the frogs.

GAIMAN: One of the things that I’ve loved about your work is you can see these lovely big change points where you suddenly go, “I’ve been doing this for a while, I’m gonna do this.” It’s always painted by him, but it’s always suddenly using new materials, new ideas, changing format, changing the way that he’s creating. How does he know? How do you know when something has become a new way of talking? The Greek mythology oil paintings are a lovely example. Suddenly you’re doing a set of giant oil paintings. At what point did it move from playing with oils and playing with ideas to suddenly realizing that you’re now making a new kind of art.

AMANO: I don’t really know where I find the point of change. In terms of the Greek mythology, I did different jobs regarding fantasy, and there was an image where I wanted to incorporate some things in the end with what I was doing for work, and then at first I was thinking Buddhism and I’d done that before. Then, looking into Greek mythology kind of clicked with me, to really show Greek mythology in my point of view. I’m actually working on a big canvas right now, like four meters by 150 meters. I want to do a grand picture of Greek mythology and that’s kind of also a continuation of this. I’ve had it in my mind for a long time. It was kind of boiling in the background, but then it was the point where it kind of boiled over and I was like, “Okay, this is the time to do it.”

GAIMAN: There is that weird thing where for me it’s very hard to say when something started because it starts before it starts. It definitely is something that you have in the back of your mind for a long time or it’s just something you go and chew over and then one day you realize, okay, I’m actually writing this. I’m working on it, I’m making it.

AMANO: I agree. You do your everyday things and some things are always boiling in the background of your mind, and then one day it just kind of comes like, “Hey, this is the time to do it,” right? I don’t want to do something that’s easy to do. I think this was something challenging that I’d never done before.

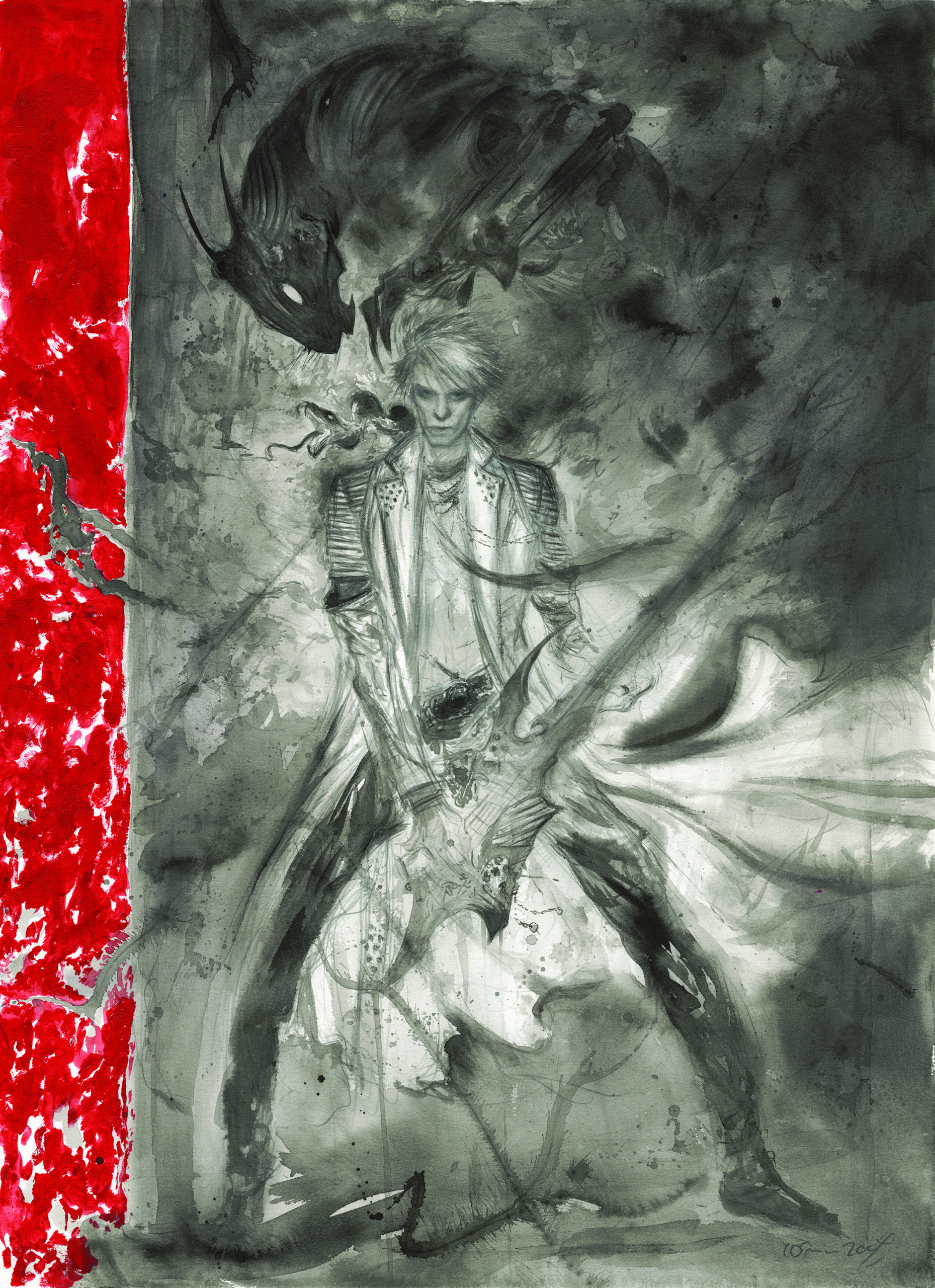

GAIMAN: One thing that I have a tiny sorrow about is so back in 2004 maybe, I don’t remember. you did some paintings of Bowie and Iman, and then I was shown them and I went, “Okay, I’m going to write a story.” The idea was that it was meant to have been in two halves and I would write the first half and then we’d do the second half, but we never got to do the second half. 10 years later, I thought, I’ve got this story sitting here and it’s half a story, and I want to know what happens next, and these beautiful paintings existed. I finished the story and I was so pleased with it that I reached out to Bowie’s people.

Bowie lived fairley near me, to the point where every now and again people will be down at the corner shop, and they’d say, I’m standing by David Bowie for a coffee. Although, I’m good friends with his son, Duncan, I always avoided him. I prefered the David Bowie in my head to actually meeting him. But when I’d finished the book, I thought I will get him a copy of Trigger Warning, the book that it was in. I sent a couple of emails out and went, “Good, I’ll do this but I’m in no hurry,” and then I went off with my wife to have Holly, our daughter, and sort of stepped away from the world for a few months, and then he died.

GAIMAN: It made me so sad that finally I was ready to send something to Bowie and I felt like it was the thing that we had made. But I love the fact that we have been working together since 1998 and because this is incomplete, it’s felt like we’re still working on something together, and it’s weirdly inspiring. I’ve never felt like I’ve stopped working with you.

AMANO: Yeah, I want to pick up the David Bowie project with you.

GAIMAN: I can imagine myself five years from now, 15 years from now, picking up the phone or getting on email, calling Akiko and saying, “Hey, there’s this thing I want to do. Would Mr. Amano like to play?”

MUKAE: Yeah, because it’s so many people, I lost contact in the US world or English-speaking world because he didn’t have anybody who can take care of this thing, so now we’re here.

GAIMAN: I’m so grateful, but I’m also just glad that the… How do I put this? I feel like I’m in a very strange world right now because for the last 35 years I’ve been doing more or less the same shit. For the vast majority of that 35 years, I was that weird guy doing that odd stuff out on the fringes. Now, I look around and the weird stuff that I was doing out on the fringes, like Netflix making Sandman, and it was the biggest show in the entire world for a month last year. It’s winning awards. Good omens. My weird little book from 30 years ago is now this huge thing. Coraline came out, became a movie and then instead of being a thing that people forgot, it gets weirdly bigger every year. I feel like, “okay, I was oddly ahead of my time,” not as a good thing or as a bad thing, but just as a thing. I was doing this stuff back then, and I’m glad I did it back then, but now that stuff that I was making feels perfectly appropriate. I feel like that was also the case for you coming to New York in 1997 and saying, “This is what I do, this is what I am. Look at my art,” and a lot of people going, “we don’t know what this is. We don’t know why you’re putting this on the walls.” I feel like now the world looks at it and goes “Oh, I understand this. I have the language to understand it,” and I don’t feel like people had the language back then.

AMANO: Also, in ’97, I kind of changed careers and started from scratch and I wanted to see what can I do? How far can I take my talent? It feels like I was meant to work with you on Sandman, that was the first project we worked together on. Came to New York with all the pop artists. I was trying to meet Andy Warhol, but they all passed away. I was like, “What’s going on?” I met you here, so it’s kind of how I felt when I first came here.

GAIMAN: It felt like the people who were seeing your art 25 years ago did not have the vocabulary to talk about what they were seeing. Because if it was pop art, then it didn’t come out of the American pop art tradition, it came from a Japanese pop art tradition. But what did that mean? How did that align with the fact that it was pop art and fine art crashing into each other—you were speaking both languages at the same time. You had the western, the more Frank Presenter kind of influence, but then you had the incredible delicacy and this beautiful Japanese, not just the manga tradition, but the fine art tradition, the delicate brushstroke tradition, all of this stuff. What was great for me was that we could do something like this and the comics people went, “Okay, we love this. We don’t know what we’re seeing, but we love this.” You kind of knew that with time, the culture would move on to the place where the fine art people would go, “Oh, we get this now.” But we had to get there. 25 years have passed, and I think people really do now. I look at your art and you can see the delicacy, the perception and you see everything filtered through your mind and hands.

AMANO: I’m not from an art background. I think from misunderstanding, art’s more like we create things that never existed before and try new things. Similar to Warhol, when I first made art, people didn’t understand. People didn’t know what they were seeing. Like you said, there is no vocabulary, so I think it’s like creating something new. Creating something that people haven’t seen before is what art is.

NEIL GAIMAN: If you do that, you’re always going to be ahead of what people like, or at least you’re always going to be ahead of the cultural mainstream until finally it catches up with you. Then we can become boring old people doing that stuff that people used to do.

AMANO: 300 years later we’ll be recognized. But that’s fine. I think that’s okay.

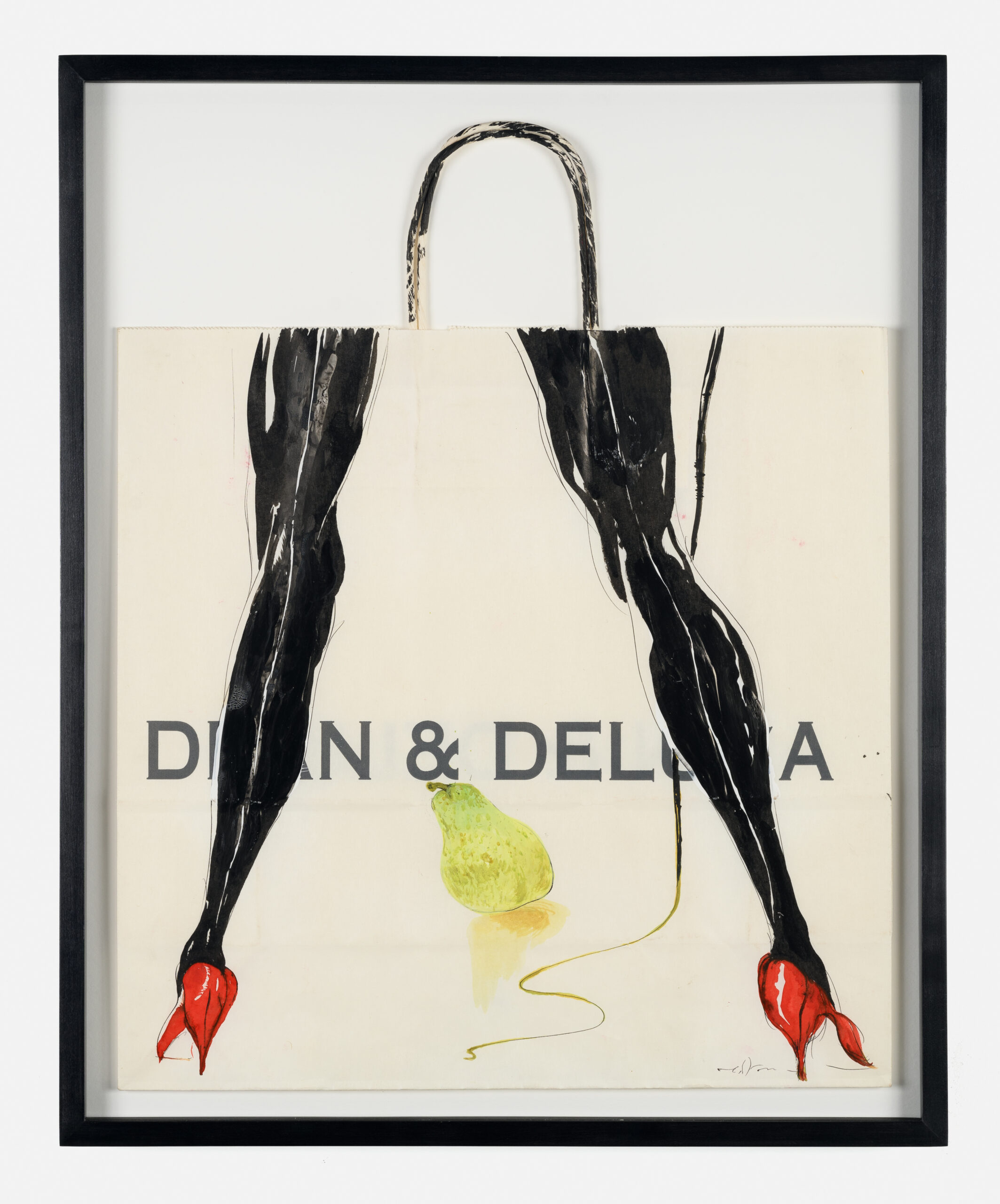

GAIMAN: I think that’s very okay. I also think for me it’s like when people talk about AI, all you can really… The point of AI is that it’s never going to do the next thing. The joy of me being a writer is going, I’ve never told this story before, I’m going to tell a story that I’ve never told before. The joy of looking at Mr. Amano’s art is going, “Oh, he’s gone off into a place he’s never gone before.” Look at these amazing ink and charcoal and water things. Look at these, the Dean and DeLuca bag series. You’re never going to be able to have an AI that’s going to go, “I think I’m going to do it, Dean and DeLuca bag series.” The best you can do is feed an AI, a Dean and DeLuca bag series and it’ll go, “okay, I can make more of the Dean and DeLuca bag series.” But it’s like, that’s something you’ve already done. It’s, where are you going next?

AMANO: I think for us it’s, your experience equals art, right? For example, the Dean and DeLuca bag, I was just eating food and looking at the Dean and DeLuca bag and I said, “Hey, you know what? I can just put what I ate on the bag.” I think our daily lives equals art, and AI right now is not a life organism. But maybe, I don’t know, 1,000 years later, AI might be living life, but for now, no, right?