ART

Wolfgang Tillmans and Douglas Stuart on Control and Queer Liberation

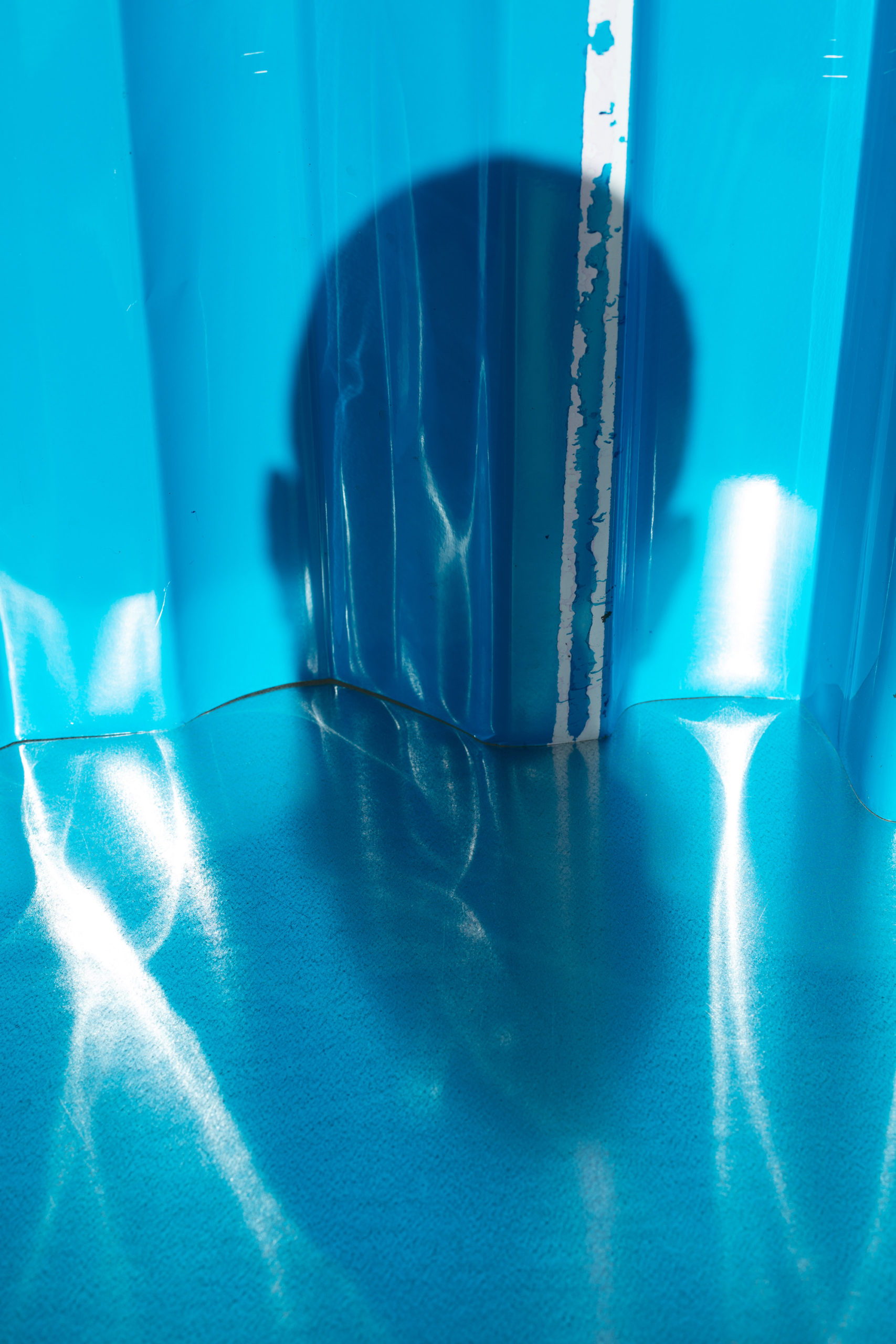

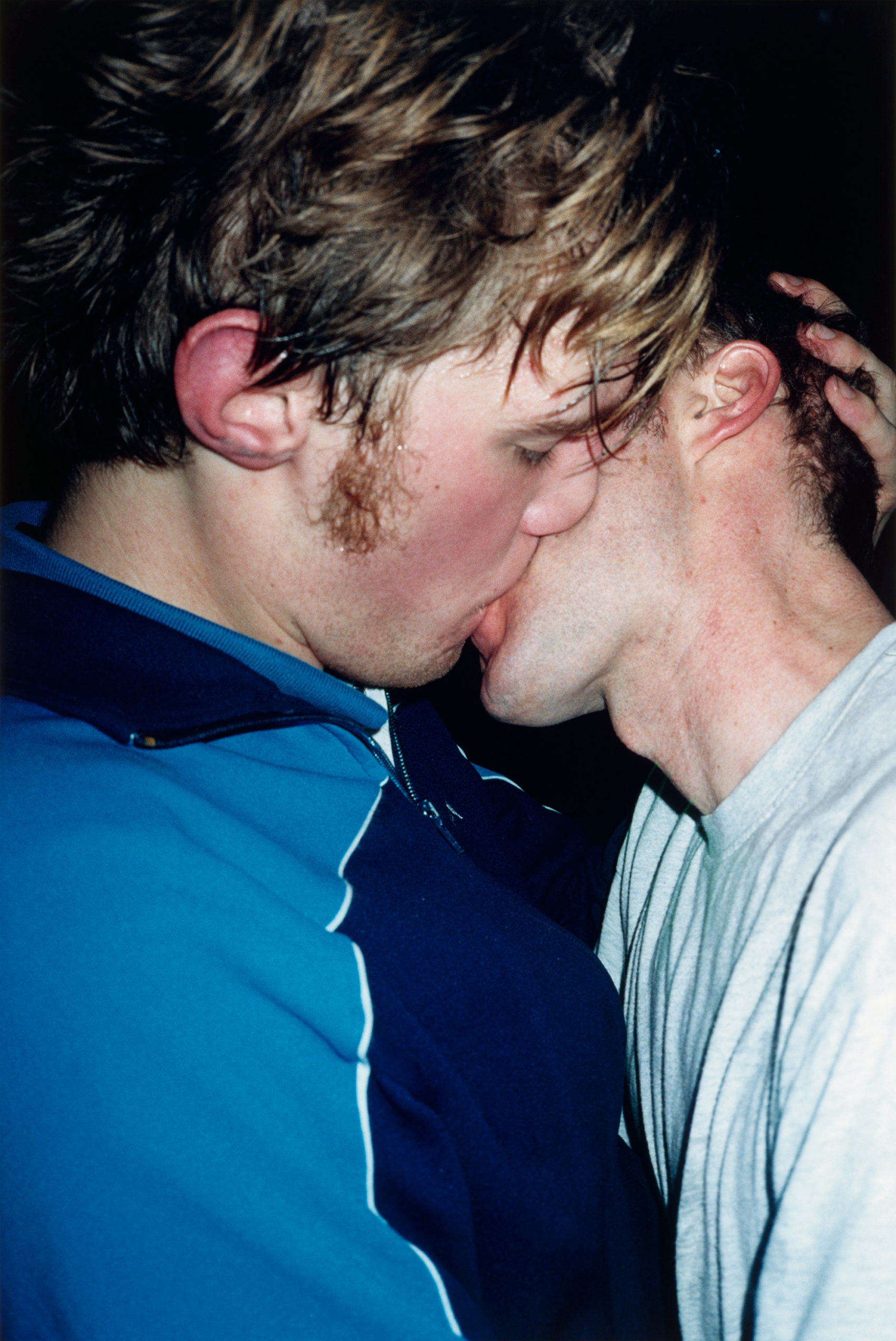

The planet of Venus passing across a giant violet sun. A man with his cock out in an airplane seat. Prisms of light or folds of paper pushed to the point of abstraction. A shirtless, green-haired Frank Ocean covering his face. There is almost no genre of photography that the legendary artist Wolfgang Tillmans hasn’t tackled in his four decade career, begun in the late 1980s shooting friends and strangers in the wilds of a newly united Berlin. This fall, New York’s Museum of Modern Art opens a retrospective of the artist’s various photographic odysseys, from the rebellious to the rarefied (sometimes within a single image). The Scottish novelist Douglas Stuart used a Tillmans photograph, 2002’s “The Cock (kiss),” of two young men kissing in a sweaty club, for the U.K. cover of his latest book, Young Mungo. Here, the two artists speak about fear, fun, and queer liberation.

———

DOUGLAS STUART: Wolfgang, it’s an honor for me to talk to you and I want to thank you for allowing me to use an image of yours for my novel. But first I wanted to ask, did you take any photos of the recent strawberry moon?

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: Ah, I did. But it’s a sad story. I did photograph the moon on Wednesday night and woke up in the morning to the message from my assistant that [artist] Juan Pablo Echeverri died that night in Bogota. He was an incredible queer icon. I’m sure you would have loved him.

STUART: I’m sorry for your loss. And to have it come at the time of the strawberry moon, which is about abundance and things blossoming and coming to life, is quite poignant. Are you planning to take photos of the planetary alignment that’s happening on Friday?

TILLMANS: Sometimes astronomy, as it’s reported in the news, is too hyped up. But there was one particular event that happened in my life, the great conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter at the end of 2020, where I looked through my telescope and I could see Saturn and Jupiter in the same frame. You could see Saturn being much fainter and Jupiter being brighter, which of course is because Saturn is much farther away. I had this feeling of real space within the solar system.

STUART: I couldn’t see the moon clearly until I was about 14. I know you grew up with a love of astronomy, but I was incredibly short-sighted as a kid, and I was hiding it from my family because I was already being bullied for being feminine. When I was diagnosed as needing really thick glasses at seven by a traveling nurse who had come to school, I lied to my family. So I still remember that moment of everything in the night sky going from this milky texture to something that had real clarity. I know you are including some of your astronomy works in your upcoming MoMA show. There are going to be about 350 works from over the course of your career. How do you go about preparing for a show like that?

TILLMANS: It’s daunting and exhilarating at the same time. If you ask 10,000 artists where they would like to show most, MoMA would be the place that most would mention. So, I feel incredibly lucky and happy that this honor is bestowed onto me, but at the same time, in terms of the practical things, it’s important for me to capture a sense of discovery and freedom and the ability to move around freely in my exhibition.

STUART: The exhibition is titled “To look without fear.” Tell me, what is looking without fear?

TILLMANS: I think of the title as a hope, an encouragement, and a demand. On the one hand, I hope that I’m able to look without prejudice, with great openness, and I hope my work is an encouragement for people to face reality, to not be afraid of seeing things how they are. But it’s also a demand that we have the right to live without fear, without looking at the truth and being punished for it. Particularly as a gay man, we grew up always with a different perspective on reality, and to look at the world in that way was induced with fear. So it’s also hope for that to end.

STUART: I was thinking about looking without fear, and how that idea keeps shifting within my own work and my own lifetime, and how we must never take our liberties for granted. The image you let me use for the cover of Young Mungo has such resonance because my relationship with it has changed over 20 years. At first, it was an image that I felt quite shocked by, because I was so unused to, as a young gay man in the early 2000s, seeing two men kissing. And then it’s something I feel very protective of now because it’s a very ordinary demonstration of love. It’s an everyday expression of desire. When I think about fear, I think about the journey that photograph may have gone on, but then also about the hatred that is brewing in America at the moment towards queer life and how terrifying that is.

TILLMANS: I saw a lot coming, but I didn’t see the “Don’t Say Gay” situation we are facing now. I thought with someone like Peter Thiel in the Donald Trump circle, that they would stay clear of directly going homophobic. But then again, why would I have thought that when they go directly misogynistic and against women’s rights? I took the picture you’re talking about in 2002. To photograph a kiss is extremely difficult. Of course there are a million kisses, but they can so easily be contrived the moment you add a third person to the mix. When two people are performing a kiss, it’s terrible, but it was the first explicit gay kiss in my work and I felt the power of it so much that I overcame my hesitation to publish it, because I didn’t know who the two were. Twenty years later, the mystery was solved and I was able to give one of them the print. He lives in Nepal now.

STUART: Really? Whoa.

TILLMANS: I put it in my first American museum survey exhibition that toured from Chicago to Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., where the picture was attacked, slashed by somebody with a key, ripped. It came as a shock. But I’ve always been struck by the fact that you can show two men killing each other at three in the afternoon in any country in the world on public television, but you can’t show two men kissing each other.

STUART: Certainly, it’s an image that has been a call for solidarity and defiance in the queer community. It was an image that was actually so central to the writing of my book. It’s funny that you talk about finding the young man in the photo, because I based the character of James Jameson on the blonde in that photograph. I fell in love. I spent hours thinking about how to describe him and these beautiful pink ears and the desire and vulnerability and tenderness that I find in that kiss. There’s a real affection and openness in your work, particularly in your portraiture. Your Taschen edition published in 1995 was actually the very first art book I bought. I was still in high school and it was all these young people living on the fringes of their sexuality, of political activism. They came into my life when I really needed them. I wonder how you feel about those photos now.

TILLMANS: That touches me, when I hear what you just said. To genuinely touch people in other countries is the best thing that can happen to an artist of any medium. I was touched by Bronski Beat’s “Smalltown Boy” coming on the radio around the time of my 16th birthday in 1984, when I had my coming out.

STUART: Scotland’s Finest!

TILLMANS: Yes! It means so much to hear how my book impacted people’s lives, how they felt no longer alone in their small town in Idaho or in a Glasgow suburb. When thinking about them for the MoMA show, I feel like they’re still connected to the now even 30 years later. I’m really grateful that they don’t seem dated.

STUART: I have such a fondness for them. First of all, I was so jealous of the fun it looked like you were having in London, that came across in those images—and a feeling of innocence as well. I wonder if your subjects in the ’90s found the utopia they were looking for.

TILLMANS: We were all looking towards a more open society in terms of the body and sexuality. My friends and I were enthused by the sense that experiencing the openness and the joy of house music and the dance floor and a street parade under the open sky would transform people in this slightly utopian way. I don’t want to say that we’ve been naive and the promises did not come true because of the pushback that we experienced politically from the authoritarian right in the last years. But now you see with what just happened with Roe v. Wade, the fight for women’s rights, the fight for gay rights, the fight against racism, has been something that’s been going on since, well, you can almost say since the French Revolution. Only lately have we been feeling a sense of security, but that doesn’t mean people aren’t still hating and pushing back against us. We find ourselves in a world that’s divided.

STUART: I was terrified by the group of homophobic rioters on their way to incite violence at the Pride march in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. That’s why the title of your show, “To look without fear,” is particularly relevant today, because we’re living in a time of increasing fear. Not to get too dark about it—this is supposed to be a light chat, but you’re talking to a Scottish novelist.

TILLMANS: Fear is the greatest incapacitator. When you want to stifle a young person’s development, you make them fearful and make them fear their own bodies. I’ve always found that instilling fear of your own body in young people is such a crime. It holds people back and it internalizes hate, and it creates self-hatred. Of course, people don’t know where to go with that and hand it on to their children. But where we go from here is obviously the big question. I feel like from a German point of view, I can’t change America. I can’t get involved in American politics. I am, of course, a global citizen in the way that my art is shown internationally, but I find the irrationality of the American public discourse [so] beyond reach, beyond comprehension, that all I feel is I want to protect what is left of the liberal Europe that I value so much, that I owe so much to, while always being aware that Europe has its own centuries of bloodshed and oppression.

STUART: Let me ask you about the process of making your images. I think one of the misconceptions about you involves this idea of quickly capturing chaos, but in fact you’re an incredibly controlled photographer. We live in a time where photographs are anything but spontaneous, although everybody is trying to capture spontaneity. But really it’s about ultimate control. What has changed in your approach to subjects over the course of your career?

TILLMANS: In the second half of the ’90s, after having put out such a strong group of images of others— images of humans, images of lives— I immediately started to question, what does this actually mean? Who do they help? How are they protected from abuse? Who controls your image? And maybe that’s what was part of the motivation for me to let the camera rest and to make abstract works without the camera in the darkroom, purely with light. I always felt that I make pictures for my fellow humans, so that they don’t need to. I know that sounds fake-selfless. I do take pictures for myself, but that kiss, for example, was purely out of a sense of duty. There was such raw, alive energy in the room that night, and for a few minutes, I snapped out of myself, out of my own revelry, and captured pictures. Today, people photograph every moment of their lives, but I never took those photographs to talk about my life. Obviously they were read that way. I didn’t want to say, “These are my friends and not your friends. This is my food and not your food.” Nowadays, so many pictures are about competition.

STUART: Bragging.

TILLMANS: Yes, and it’s particularly bad because people don’t even know how a camera works, how a lens works, what distortion is. People are forced into using a language that no one ever told them how to speak.

STUART: It’s not about a love of photography. It’s about self-promotion. But one of my favorite works of yours is the “Concorde” series [1997] that took me so many years to understand, which is an entirely different approach to framing what’s meaningful.

TILLMANS: I had a big exhibition at Tate Britain in 2003, and I called it, “if one thing matters, everything matters.” This title was misunderstood as me saying that everything matters the same, that there is no difference between anything. That’s not what I meant. What I did mean and what I want people to feel in the work is that potentially the mind, our mind, your mind, has the power to transform an object of low perceived value into something of high beauty, or a moment that is fleeting and not considered special can be viewed as very precious. I didn’t feel that I wanted my photographs to stand on a pedestal or build a barrier between the viewer and me.

STUART: Do you feel like you’re still learning?

TILLMANS: Yes. I hate to feel stuck. I always want to try new things. It’s fascinating how we accumulate knowledge over life only to die one day.

STUART: My last question involves New York. You used to live there, right?

TILLMANS: I lived there in the ’90s, on 14th Street between Sixth and Seventh avenues with an incredible view out onto the street. I made a 27-minute video there, which I’m excited to show at MoMA the week after the opening. I have felt very close to New York, especially in the past few years. I feel there is a common wisdom to all New Yorkers that is unique. Everything is magnified in New York and yet its common humanity is amplified as well. It’s also insanely alive. That’s why I still love it.

STUART: That’s a good way to end. Huge congratulations. I can’t wait to see the show.

———

Images courtesy the artist; David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne; Maureen Paley, London