ART!

With prepare my heart, Kia LaBeija Remembers Her Mother

Kia LaBeija is dedicated to depicting the realities of life with HIV. The dancer and photographer contracted the illness from her mother Kwan Bennett, a steadfast activist who died of AIDS in 2004, but her work is not simply focused on disease and mortality. Rather, LaBeija’s photography communicates the tenderness of her relationships and the abiding inner strength of her subjects. Her self-portraits convey regal poise and immense vulnerability. Her landscape photos capture Manhattan in bursts of beauty. Some of her images are formally composed, sexy, and otherworldly, while others reveal deep bruises left by a lifetime of medical precarity and stigma. In addition to her photography practice, LaBeija is an internationally recognized voguer who was once the Overall Mother of the House of LaBeija—the groundbreaking ballroom house founded in the 1970s. This week marks the opening of LaBeija’s first ever solo museum show, prepare my heart. The deeply moving exhibition, on view at Fotografiska until Mother’s Day (May 8th), presents a combination of the artist’s self-portraits and landscapes, as well as family photos and ephemera. To mark the show’s opening, LaBeija sat down for a conversation about motherhood, memory, and triumph.

———

CONOR WILLIAMS: I’m curious about what your first artistic love was, whether that was dance, or photography, or something else.

KIA LABEIJA: My first love was dance, for sure. There are videos of me at, like, three years old, dancing to Michael Jackson. Janet Jackson was one of my all time favorites. I saw “The Pleasure Principle” when I was a kid—it was all over after that.

WILLIAMS: When did you realize that was something that you could turn into a practice?

LABEIJA: I came from an all-around artistic family. By the time I was three or four, my brother was already doing commercials. He did a movie called Boomerang with Eddie Murphy and Halle Berry. My dad’s a musician, he’s played with everyone from Whitney Houston to Nina Simone, and my brother’s mom danced for James Brown for ten years. My parents met working on a show, where my mom was a stage manager. I was born into this family of people who really pursued creative careers, so it was never a question.

WILLIAMS: That’s crazy. I first saw your work back in 2016 in the exhibition Art AIDS America at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. I remember that show faced criticism for the paucity of black artists featured. Do you feel that the tent has gotten any bigger?

LABEIJA: Art AIDS America–that was a hard one. It was presented to me as, “This is going to be the first big show to look deeply at artwork that came out of the AIDS epidemic…” and it was actually reflective of what I think the AIDS narrative has always been. The people that were included in the show are the same people that we always talk about when we talk about AIDS. Has it changed since that show? I don’t think so. It’s never surprising that alternative narratives are not included. A woman who was a social worker in the late ’80s in Florida sent me the introduction to a book that she’s writing about women and children in the AIDS epidemic. It was so touching to read, and it gave me a perspective on aspects of the epidemic that I didn’t even think about. Women are also cooking, cleaning, taking care of kids, and taking care of themselves. When I think about my mom…how did she do so much to make me feel so loved, so cared for, and so safe, even though we were dealing with what at the time was a terminal illness. How did she manage to keep clothes on my back and make me feel nurtured? How do women like her, or who have very similar stories go unnoticed? I don’t even think women have the time. Mothers do not have the time to deal with all the extra stuff that comes with being open about living with HIV.

WILLIAMS: There’s this old Gran Fury piece that said, “Women don’t get AIDS…”

LABEIJA: “…they just die from it.” Exactly.

WILLIAMS: Today would be your mom’s birthday, right?

LABEIJA: Today is my mother’s birthday. She would have been sixty-five!

WILLIAMS: Can you tell me about her?

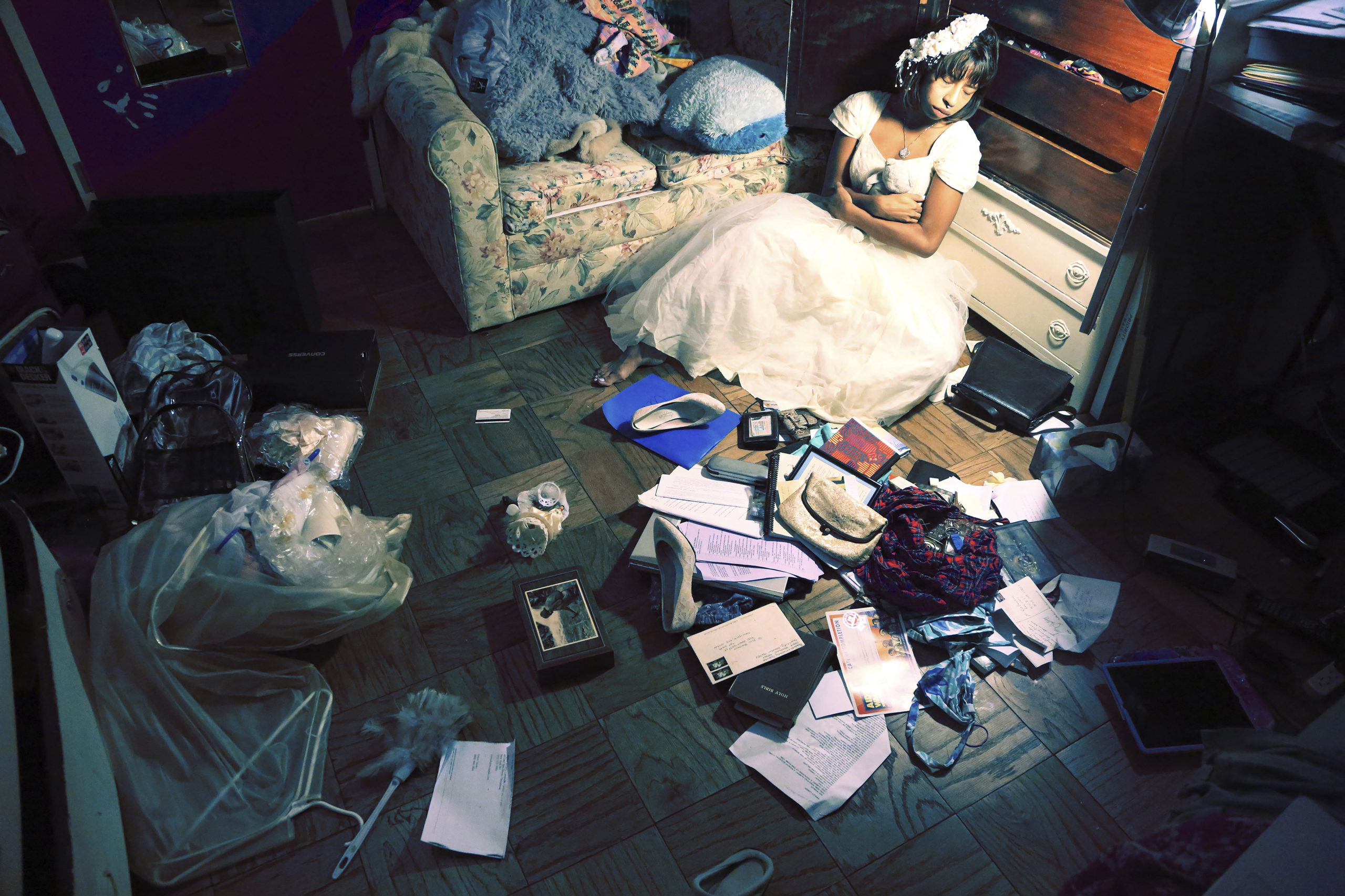

Mother’s Day (1997).

LABEIJA: So many people have been asking me that question, and as soon as they ask, I’m speechless. My mom always felt–to me–like a very happy person. Even with everything she was dealing with, she always seemed positive. She was giving and loving. She would literally give you the clothes off her back. There were always people staying with us in the house. Always cooking. Very welcoming and very warm. Beautiful—like, naturally beautiful. I never really saw my mom wearing makeup, the only nail polish I ever saw her wear was a pearl color and I always thought it was so beautiful. I actually started wearing it recently. She only wore silver jewelry, she hated gold jewelry. She was very supportive of me in every way. Anything I wanted to do, she’d make happen, whether we had money or not. We’d find furniture and stuff off the street and she’d bring it in and reupholster it and make it look brand new. She rearranged the furniture in the house every couple of days. Whenever my school friends and I would talk about my mom, they’d always say, “Every time I come to your house, the furniture is completely different!” She was deeply spiritual. She liked to talk. She loved movies. She loved to write. She wrote in these notebooks that I still have. Some of them were written specifically to me, and some of them were journals of whatever she was going through at the time. When I read those journals, there was so much inside of her that I never saw, because of the way that she took care of me. She always came to me with a smile. We were best friends. We could talk about anything. She never hid things from me. She didn’t want there to be secrets. She was a beautiful dancer. To me, she was Superwoman.

WILLIAMS: Some of those notebooks are in your show, prepare my heart. It felt like such a big family project. All the contributions from you and your mom and your dad…

LABEIJA: I wanted to involve as many people from my family as I could. My favorite photograph of my mom is taken by my Auntie Cindy. It’s in the show. After my mom died, I slept with that photo for years. Of course, I wanted my dad’s voice in the show, because he’s very much a part of the story, but he’s more private. My brother took all the footage of the early years of my life, which was super important, because I can still see my mother and hear her voice. It’s crazy, I hear her voice in those recordings now and I’m like, “oh god, that’s my voice.” I’ll never forget, one day she walked me to the school bus and she laughed about something. She goes, “God, I sound just like my mother.” I laughed with her, and she was like, “Don’t you forget this moment, because one day you’re gonna do something just like me, and you’re going to think of this!” I swear I never forgot it. As soon as that started happening, I was like, “She was right!” People tell me all the time that I look just like her.

WILLIAMS: I used to think that I didn’t look like my dad, but more and more…

LABEIJA: You just morph into your parents! It’s so weird.

WILLIAMS: Speaking of motherhood, you were also the Overall Mother of the House of LaBeija. Is there anything that your mom taught you that you brought into that role? Or is there anything that you learned from the house that you bring into your personal life or artistic work?

LABEIJA: Before I had that title, I had the ability to nurture the house more than I did after I got the title. Once someone gives you a title…it becomes a whole other thing.

WILLIAMS: Why do you think that is?

LABEIJA: Honestly? Power. You know, the House of LaBeija is the oldest house in ballroom. There’s a lot that comes with that. It’s hard to navigate a house that has such a legacy. It can be difficult when you have a vision, and you are trying your best to work as a team. I’ll leave it there, I don’t want to say too much about that. A lot of my favorite memories from my time in the house come from walking the balls. That was the best part. You can be whoever you want to be. It’s fun when a flyer comes out and you’re like “Oooooh, the category is… Okay!” And then you prep. That part is super fun. I’m going to come back one day, and I’m going to walk an unexpected category. Something people wouldn’t expect me to walk. I’m not going to say which one.

WILLIAMS: Keep them on their toes.

LABEIJA: The ballroom can feel very glamorous, romantic, but also like a soap opera. And some good reality TV. [Laughs] The drama can be enticing and a little sexy—sometimes not so fun, definitely—but it kept life exciting and I definitely took a lot of who I was as a figure in ballroom into who I am in my self-portraits.

WILLIAMS: What inspired you to take the name LaBeija, rather than your family name?

———

LABEIJA: My given name is Kia Michelle Benbow. I really just go by Kia. I still use Kia LaBeija because it’s the name I’ve built and it’s recognizable. I’m not a member of the House of LaBeija anymore, so I’m trying to find my own way just as Kia. Sometimes you just want to be somebody different. When I came into the House of LaBeija, and I felt this exuberance and excitement, people would see me walk and they’d be like, “Okay, Miss Kia LaBeija!” It’s fab. It just stuck and it’s probably going to stick forever. I also like it because it’s a historical name to people of color, to queer people. I love being that person, but I started to realize that I didn’t just want to be somebody at night anymore. For a while, I was very much in the club scene and the ballroom scene. My life was at night. That’s fab, and I love that, it’s very New York. But I wanted to peel back the layers. I felt like using the name Kia LaBeija gave me a mask, it was easier to talk about HIV while playing that character. After a while in that world, you hang out with the same people in the daytime, and you’re like, “Oh, we don’t really know each other too well.” I wanted deeper connections. I needed something more than the fantasy. That’s not to say that Kia LaBeija isn’t a part of who I am: you can see in my pictures from childhood, I’ve always been the dress-up queen. That’ll never go away. So I guess it’s not totally a mask, but it’s been…a platform. I don’t know, people respond to things that are pretty and beautiful. If I’m talking about HIV and AIDS and I feel pretty and beautiful, which is not how I feel a lot of the time on the inside, it feels like it gives me more power, strength, more confidence. So I think that’s really what it is.

WILLIAMS: You said something about the nighttime. I love the way you use light, especially in your self-portraits. How does light inform how you present yourself?

LABEIJA: One of the things that I love about New York is the way that light jumps off different buildings. Especially in the fall. The way that sunlight hits windows and reflects back is so romantic. I think everyone is the most beautiful in the sun. So, there’s two ways that I use light. One–I love to use natural night as much as possible. It’s like the Earth is telling you, “This is your moment. I’m giving you the spotlight.” Two–I love spotlight lighting. Usually when I light my photographs, I use whatever’s already in the room.

WILLIAMS: There’s also a really interesting lack of light in some of those self-portraits.

LABEIJA: Oh, yeah. There’s a lot of darkness in the photographs as well. Sometimes it makes you look a little bit harder. And if you keep looking, you’ll find all these different things. Because I use home spaces so much, the objects that you see in the space can tell you so much about the subject, which is usually me. So many of those items pop up in multiple photographs over the years. There’s something that’s so special about the ephemeral part–not just having the ephemera, but seeing the ephemera travel throughout the images. I love being able to play with time and photograph the same place over and over again as it changes and I change. I’m about to be thirty-two. My mom and I, our birthdays are a week apart. She’s March 11th and I’m March 18th. And her mother was born on the 14th. It took a long time for me to be able to celebrate my birthday after my mom died. We’d always have joint birthday parties. My aunt told me recently, “Your mom, every year, wanted you to have the best birthday, because we never knew if you were going to have another one.” That put a lot into perspective. Every birthday was really special. So when we weren’t able to celebrate our birthdays together any longer, every birthday was really difficult. Then in 2014, I had a big birthday party for the first time in a long time, and everyone I knew came. I’m hoping that this year will be similar, because I haven’t seen my friends in a long time.

WILLIAMS: Right. Two years…

LABEIJA: Two years. I’ve been very cooped up in the house, very safe, trying not to see people if I don’t have to. So this is the first time I get to see all my friends again.

WILLIAMS: When you take a photograph, is there something in particular you want to achieve?

LABEIJA: It’s partially capturing a feeling, and it’s partially documenting. I think of a lot of my self-portraits as half-documentary. I’m usually in the middle of doing something when I take the photographs. It’s usually like, I’m in a space and a headspace, and I want to capture this moment in a certain way. Almost like holding onto a memory. I’m always thinking of how to make it feel poetic. That’s where the lighting and the staging comes in. I’m also thinking, “What story will the photo tell?”

WILLIAMS: You’ve also put out a View-Master featuring your photographs. How did you decide to do that? That’s so cool.

LABEIJA: Oh, man. I grew up in an apartment in Manhattan Plaza. Manhattan Plaza was an amazing building for artists that was built in the ’70s. Times Square was very seedy, filled with working girls and drug dealers and it wasn’t a very family-friendly place. It was like the Wild Wild West back then. Since nobody wanted to live there, they thought, let’s have these buildings for artists and we’ll make it income-based, so that the artists can stay in New York and do what they need to do. My father moved into that building in the ’70s. He actually lived a couple floors above Larry David, I think. Seinfeld is based on his experience of living there. The real Kramer, I think he still lives there. And he does these tours…it’s kind of wild. So yeah, my dad lived above him and he was always banging on the drums, and Larry would come up and be like, “It’s too loud!” My dad was always a little upset that there wasn’t a character based on him in Seinfeld. Over all these years, I watched all these buildings come up. All of a sudden my view changed. I couldn’t see the ball drop anymore, I couldn’t see the Empire State Building from our balcony. As I grew up, I knew I was going to lose that view that had meant everything to me. It had been one of my biggest inspirations. So I started photographing it ten years ago. I wanted to see it as if I was still there, and it was still there. Eventually I decided to do a View-Master, and the Museum said they were interested in supporting the project. Honestly, it’s super selfish of me–I click through it and it just makes me feel like I’m standing looking at my favorite view. Regardless of whether anyone else buys it, I just made it for myself. It’s a way to hold on to something. There’s so much of that in what I’m doing with my photographs. I want to be able to hold on to a memory or a moment, but I also want to grieve it and let it go. Both of those things are happening at the same time.

WILLIAMS: The show is bittersweet, but joyful as well. How did you go about striking that balance?

LABEIJA: I really don’t know. It’s interesting, people take away different things. I remember at the opening, some people were like, “Wow, the exhibition was so sad.” Like, oh…thank you… [Laughs] I didn’t know what to say to that. Most people were able to see the sadness, but also the triumph. I wouldn’t say there are a lot of happy moments, but there’s definitely triumph.

WILLIAMS: There’s light.

LABEIJA: It’s that balance between night and day, between the pain and the beauty. Some of my childhood images balance it out. In my self-portraits, I’m usually not smiling, which is interesting. My dad, whenever he took photos of me, he’d be like, “Smile!” I guess I’m like my mother. Smiling on the outside, but on the inside, there’s so much happening. So, I’m not smiling in a lot of my later photographs, because I’m in a pensive mood, or I’m somewhere else. But the family photos balance that out. Because in every photo of my mom, she’s smiling, except for the one where she’s asleep. That’s a photo that my dad took. I wanted to include it because, when I look at it, I’m reminded of the last time that I saw my mom. Her eyes were closed and she looked like she was resting. Well, that’s not true—the last time I saw her she looked absolutely horrible and I would never want to describe to you what she looked like. But the couch that she’s sleeping on in that photograph by my dad is the same one I was sitting on when my dad told me that she had died. He got a phone call and he turned off the TV and turned to me and was like, “Mom is gone.” And then we went to the hospital…but I like that photograph. I like that she’s resting. I like to think she’s dreaming, she’s in some other dimension. I think the thing that I like about those family photos is that it was a really hard time, those early years, but we still had so much fun. There’s so much love, and there’s a lot of triumph in that. I don’t think all of my self-portraits are sad, but a lot of them are exploring a deeper issue that’s not necessarily a happy issue.

WILLIAMS: Before we go, is there anything else you’d like to say in memory of your mom?

LABEIJA: Days like today are so interesting. The more time goes by, the easier…the easier it gets? Maybe it’s not that it gets easier, but you get used to a life without a person that you love. You miss them, but you know it’s not day one. I have so many good memories with her. We used to go to Central Park a lot. My mom’s ashes are in Central Park under what used to be this beautiful willow tree which got cut down in maybe 2016 or 2017, and I was devastated, because that was our tree. I was in Central Park and I went to show it to someone, and I was like, something’s wrong. And then I saw that it was gone and I ran and fell to my knees and I was crying and it started raining out of nowhere on this sunny day. It was really dramatic. (Laughs) But we used to go to Central Park all the time. She’d swing me on the swings, we’d get ice cream or hot dogs, and we’d sit under that tree. My grandma’s ashes are also under that tree. Those are some of my favorite memories. There are so many, but nobody’s asked me that in a really long time, so it’s hard to think of one on the spot. But definitely Central Park. Very New York of us to spend so much time there.

prepare my heart is on view at Fotografiska Museum until May 8th, 2022.