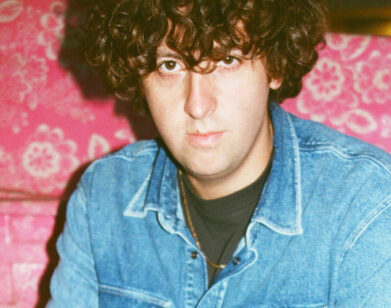

William Eggleston

Unlike Southern militias, Southern artists are primarily considered poets, not rebels. It just so happens, though, that the South’s greatest living photographer, William Eggleston, is both. Now 69 and a resident of Memphis, Tennessee, Eggleston not only single-handedly introduced color to the land of art photography, but also invented a visual language composed of gas stations, bar lights, parking lots, shopping carts, and motel rooms couches, that exceeded the power of traditional black-and-white landscapes and studio portraits. In his nearly 50-year career, currently getting full exposure at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art’s retrospective “William Eggleston: Democratic Camera, Photographs and Video, 1961-2008,” the master photographer has chronicled the everyday lyrically and without falling into sentimentality. This past September, Eggleston and his son Winston drove from Memphis to Nashville to hang out with writer, photographer, and filmmaker Harmony Korine. They sat on Korine’s porch to talk.

Harmony Korine: We’re out here sitting on my front porch, right across from Belmont University. You were saying that your mom went to school there for a little bit?

William Eggleston: For a little bit.

HK: And you went to Vanderbilt. When did you get your first camera?

WE: That same year. I came to Vanderbilt as a freshman in the fall of ’57. I got it at a place called Dury’s down on Church Street. It was a Canon Rangefinder-35mm, of course.

HK: What made you want to get it?

WE: My friend who I went to boarding school with was interested in photography. He insisted that I buy a camera and marched me downtown.

HK: I’m curious about the time when everything was black-and-white and you really started getting into color photography. What made you go in that direction as opposed to Walker Evans-like photography?

WE: Black-and-white photography, which I was doing in the very early days, was essentially called art photography and usually consisted of landscapes by people like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. But photographs by people like Adams didn’t interest me. And what we called photojournalism, the photos seen in places like Life magazine, didn’t interest me either. They were just not good-there was no art there. The first person who I respected immensely was Henri Cartier-Bresson. I still do.

HK: What was it like meeting him?

WE: He couldn’t understand why I was working in color. He said something to me like, “Don’t you think it’s ridiculous?” If so, I spent an awful lot of years wasting my time.

HK: Was there a reaction to your working in color?

WE: Well, yes. A lot of my friends were mostly working in black-and-white-people like Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and others. We would exchange prints with each other, and they were always very supportive of what I was doing. What each of us was doing photographically was entirely different, but we were basically coming from the same place, sort of like a club.

HK: Didn’t you feel any pressure to leave Memphis, where you live, and move to New York?

WE: No. I would go there quite frequently. I met and became close with John Szarkowski of the Museum of Modern Art. He was incredibly supportive about me working in color.

HK: Your first big show was at MoMA in 1976?

WE: Yes. The immediate reviews were very hostile, but they didn’t bother me-I had the attitude that I was right. The poor guys who were critics just didn’t understand the works at all. I was sorry about that, but it didn’t weigh on my mind a bit.

HK: You knew eventually that people were going to catch up. It was just a matter of time?

WE: I felt that way . . . and it came to pass.

HK: Do you remember the last time that you got into a physical altercation, like a fight?

WE: I don’t think that I’ve ever had one.

HK: That’s amazing. What about music? Did music play a part in your early life?

WE: I would play music every day from the time I was about 4 or 5 years old. Every time I would go from one end of the house to the other, I would pass the piano and play a few notes.

HK: So music was one of your first great loves?

WE: That’s right. And I’ve never stopped. I still play all the time.

HK: I heard you play when I went to your house. It was great. Did you ever meet Elvis?

WE: No, I didn’t. But we had the same doctor Dr. Nick [Dr. George Nichopoulus].

HK: For me, growing up in Nashville, there was a visual side of America that I’ve since noticed is slowly starting to disappear. I want to know how you feel about it-the disappearance of that certain visual America.

WE: I knew it was happening, but I never paid much attention to it . . . just to the passage of time. Something new always slowly changes right in front of your eyes-it just happens.

HK: For your early photos, did you know that there was a unique aesthetic quality around you?

WE: I don’t think I thought that way.

HK: It was just taking pictures of what was around?

WE: Yes, what was there at the time.

HK: And as the years passed, as you were photographing some of the same places, did you start to think, Wow, things looked better here 10 years ago-the colors were more beautiful here in the ’50s.

WE: I never thought that way. I would have probably stopped to think about it if somebody mentioned it, but that didn’t happen.

HK: So you didn’t lament the passing of old America? You’d photograph a Kroger or a Piggly Wiggly [supermarkets], and I’m sure at the time they seemed common and maybe even architecturally bland. But now there’s a beauty and a strangeness to the old Kroger.

WE: It was something new that was happening everywhere. You couldn’t miss it. If you needed to go to the grocery you would go to the predecessors of the big supermarkets of today.

I’ve also never had favorite pictures. Or subjects. I have discipline of treating everything equally.William Eggleston

HK: Would you take photos of a Kroger today?

WE: Certainly.

HK: And do you think it would have that same effect looking at it 20 years from now?

WE: I think so.

HK: So you think time makes things more exotic?

WE: I don’t think exotic is the word.

HK: So what do you think happens?

WE: Well, probably the best way to put it might be that at some time, not just in an instant, but over some period of time I became aware of the fact that I wanted to document examples like Kroger or Piggly Wiggly in the late ’50s, early ’60s. I had the attitude that I would work with this present-day material and do the best I could to describe it with photography, not intending to make any particular comment about whether it was good or bad or whether I liked it or not. It was just there, and I was interested in it. That’s what I still do today.

HK: Do you see things now that you get just as excited about? Places, areas, specifically in the South?

WE: I don’t think that has ever changed. I don’t think I see any more or any less than I did years ago. Let’s say I have the print of a photo taken in the 1960s and one I took a month ago. I think it’s pretty difficult to tell any difference, personally.

HK: Sometimes when you’re driving and you look out the window, do you ever think, That would be nice to photograph?

WE: Oh, quite frequently.

HK: Do you always have a camera with you?

WE: Not always. Almost always. If not on me or in the glove compartment, then at least in my bag.

HK: Have there been times in your life when you wished you had a camera?

WE: Yes, but I don’t dwell on them because they pass in an instant.

HK: Are there any particular images that you’ve never been able to get out of your head?

WE: Not that I can think of. I’ve also never had favorite pictures. Or subjects. I have this discipline of treating everything equally-I used to say “democratically.”

HK: You kind of edit as you go. In some ways you work opposite of how a lot of photographers work today.

WE: Exactly. They take too many pictures.

HK: Well, it’s playing the odds, right? If you take a thousand photos-

WE: It doesn’t mean that one is going to be good. That’s the problem.

HK: You can take a thousand photos and they could all be terrible.

WE: Generally, that’s what happens-a fundamental rotting of the idea. They woke up with the wrong idea. It’s just like music: If you don’t have an innate love or calling for it, then no matter how much you study or how well you can play by looking at the score, it doesn’t mean that you’re going to make really good music.

HK: It has more to do with what’s inside you.

WE: It has to do with what can and can’t be taught-you can’t teach composition. Where would you begin?

HK: Do you have any favorite bars?

WE: No, I have some that I have become a well-known-even infamous-client of, mostly in Memphis. But a great deal of that is legend and doesn’t have anything to do with truth. Many people one meets in life somehow think they know you simply because they’re hanging out at the same counter-but they really don’t know a thing about you.

HK: Do you have friends that you used to just drink with or hang out with, like, from the ’60s or ’70s-from the early days?

WE: Unfortunately they’re practically all dead. And many were my closest associates: friends, co-directors, whatever you want to say-my partners in crime.

HK: A lot of them died from drinking?

WE: Some, yes. A person can attack that bottle of vodka and drink it like it’s a bottle of cold water. Two of my wife’s girlfriends died from drinking. They weren’t big pill-takers; they were drinkers. So it can’t be so simple as to slide away, like Marilyn Monroe-

HK: They overdosed?

WE: Overdone something.

HK: Do you hang out at bars as much now?

WE: Hardly at all. Remember, all my friends are dead. I don’t have anybody to meet up with. [laughs]

HK: You outlived them all.

WE: I certainly have.

HK: And why do you think that is? Just genetics?

WE: I think genetics. My mom lived to be pretty old and my grandmother lived to be 100 and ate like a bird. I eat like a bird almost.

HK: Have you ever tried psychotherapy?

WE: Only the few times I’ve been to so-called treatment centers, which were a complete waste of money and useless. I didn’t know what I was doing at the time, because I was always drunk when I checked in.

HK: Did you check in voluntarily?

WE: Half voluntarily, half Winston’s older brother [William] would take me in, saying, “Daddy, I think you oughta do this.” And I’d say, “I think you’re right, maybe I do need it.” Sometimes a week later I’d leave the place; sometimes I’d stick it out for a month.

HK: Did you have tough detoxes?

WE: No. Never. I never hallucinated during my d.t.’s. They weren’t easy, but not-

HK: Not horrific. I was in a room once with someone who was going through it. An old guy, I guess he had been addicted to moonshine-

WE: Moonshine is very strong.

HK: Well, this guy would make it in the stills, and he was having his d.t.’s and he’d be having hallucinations of leprechauns, you know?

WE: How did he know what they looked like?

HK: He would have these visions. Like, he would say they would just jump up on him-leprechauns and frogs and things like that.

WE: Did that really distress him?

HK: Yeah, he’d be really tortured during that and they’d strap his arms down so he couldn’t hurt himself.

WE: I’ve heard about that tons of times, but that didn’t happen to me.

HK: That’s good. I wanted to ask you about 1980. You went to Kenya and created a body of work called “The Streets Are Clean on Jupiter,” right?

WE: I’ll tell you where that title comes from. One summer two years before that, in Memphis, there was a festival of old Western B-movie actors, and I became friends with one actor named Lash LaRue. And out of the blue one day, he said, “You know, Bill, the streets are clean on Jupiter.” I have no idea where that originally came from, still don’t.

HK: I’ve never seen those Kenya photos.

WE: They’ve never been published. There are a lot of unseen projects. When a project is finished, I often physically, and in my mind, set it aside,

intending something to happen with it, something that does or does not always happen. Now, a lot of these are being resurrected for the public.

HK: What about digital photography?

WE: Don’t know anything about it.

HK: Have you ever shot with a digital camera?

WE: As I said, I don’t know anything about it. I don’t know, I might love it.

HK: You’re not opposed to it?

WE: There’s plenty of film out there, and quadrillions of cameras that use film-I don’t think it makes much sense not to use it. The thing that’s going out is the manufacturing of the paper. Incidentally, all these years my wife has told me that I’m color-blind.

HK: You’re color-blind?

WE: Yes.

HK: That would be amazing if you were color-blind. If you had to choose between being blind or being deaf, which one would you choose?

WE: Don’t know. I don’t have any experience with that, except for my color blindness.

HK: But if you were forced to make the decision.

WE: I think with being blind the one thing you would have going is that you could still feel things, see your way around so to speak. And if you had had the experience of seeing at one time in your life, then you would know what it was like and be able to function. I’ve said this before, I think I could really photograph blind if I had to.

HK: It would be possible to photograph blind?

WE: I quite frequently don’t look through the camera, which is very close to being blind.