Will Gompertz: Manet, Mummies, and Modern Art

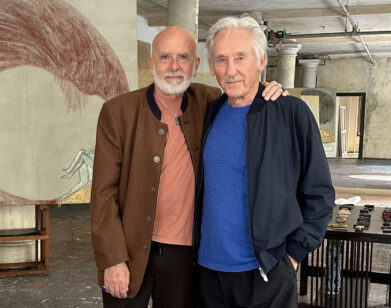

ABOVE: WILL GOMPERTZ AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM. PHOTOS BY VITA HEWISON.

“Oh, I don’t know anything about modern art…”

Formerly the director of the Tate gallery in London and now the arts editor at the BBC, Will Gompertz hears this self-preserving sentence a lot. We tell children “there are no wrong answers” in the humanities, but when talking to a curator or collector, the topic of visual art in particular seems filled with wrong answers.

Most people, Gompertz insists, underestimate their knowledge of art. “What they really mean,” the writer and curator explains in the preface of his new book, What Are You Looking At?, “is that they might know something about modern art—that Andy Warhol made an art work containing some Campbell’s Soup cans for example—but that they don’t get it… they suspect, in their heart of hearts, that it is a sham” and “find that it is not socially acceptable to say so.”

As someone who did not develop an interest in art until adulthood, Gompertz is determined to dispel the layman’s fear of the modern art world and those who inhabit it. What Are You Looking At?, which comes out this week, does a very good job of this—replacing isolating esotericism with witty and chatty commentary. Accessible and familiar, What Are You Looking At? traces the evolution of modern art from Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain to Jeff Koons, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Ai Weiwei, and Banksy. “The book is really an old story told for a new audience,” Gompertz tells us.

We recently met Gompertz at the British Museum in London to visit the Egyptian mummies and talk about exhibition titles, Sacha Baron Cohen, and what exactly Gompertz looks for in a piece of art.

EMMA BROWN: In the preface you mention, “A child of four can draw with more ability than I can.” How did you become interested in art?

GOMPERTZ: Yeah. [laughs] I was a late starter. When I was about 24 years old, I had a new girlfriend and I arranged a weekend of debauchery in Amsterdam and she negotiated that, if we were going to do that kind of stuff, then we must take in some culture. She said she wanted to go to the Stedelijk museum, which had actually just opened. I couldn’t think of anything worse but I said “All right, that’s your negotiating point.” We went there and I was going around being badly behaved and bored and then she showed me a painting by Willem de Kooning, Rosy-Fingered Dawn at Louse Point. I dismissed it initially and then I kept on having to come back to it and I ended up spending two hours in front of this painting. I couldn’t work out what it was about it that I thought was so beautiful, but it completely bowled me over. The upshot of which is that I left Amsterdam in love with that girl and in love with art, particularly modern art. Here we are, a near quarter century later, I married her and had four kids and have written a book art.

BROWN: Oh wow, so this girlfriend is your wife. Does she ever gloat about having introduced you to your destiny?

GOMPERTZ: Yeah, we talk about it a lot. We think it’s funny—it’s just one of those moments.

BROWN: In one chapter, you talk about the curator Roger Fry and the importance of coming up with a unifying exhibition title—how Fry invented the label “Post-Impressionist,” which everyone uses today, but his exhibition “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” was a huge failure because people didn’t understand the title at the time. What’s the most difficulty you’ve ever had with coming up with an exhibition title?

GOMPERTZ: They are a nightmare. They’re just such a difficult thing to come up with. I think the most memorable incident was actually not a particularly great title. We had an exhibition of Salvador Dalí at Tate Modern and there were also some films that he’d been involved with, with Brunello. The curator was very keen on the films, and we ended up negotiating and calling the exhibition “Dalí and Film,” and absolutely nobody came because nobody’s interested in Dalí’s film or his opinion on film. It was a disaster. It was supposed to be a big Tate show. After three weeks of nobody pitching up, we changed the title, and just changed it to “Dalí,” and suddenly hordes of people came. [laughs] It was really instructive—if you do something with the wrong title, you suggest the wrong thing, it’s a total disaster. If you get the right title, the opposite can happen, it can really ignite the show with people coming who perhaps wouldn’t have done otherwise. That’s the incident that made the issue of titles and their importance really profoundly obvious to me.

BROWN: Do you think a simple title—just the artist’s name—is better?

GOMPERTZ: Always. Always. “Manet and the Post-Impressionists,” sweet and simple. I think the more clever or esoteric the title, the harder it is. People glance at posters, they glance at the paper. They need the bare minimum of information to know what [the show] is about it. Group shows are always much harder to present to the public because there’s a theme to the show. They always do less well because a theme is a harder thing for people to grapple with than a monographic idea.

BROWN: How about coming up with your book title, did you have a similar period of anguish?

GOMPERTZ: No, I kind of knew that. I knew that very early on. “What Are You Looking At?” seemed like a title that described what I was trying to write, which dealt with [the problem] most people find when they’re dealing with modern art, that they don’t really know what they’re looking at.

BROWN: I’m curious as to how precarious the position of the curator is today. If one of your titles fails, like “Dalí and Film,” is it a strike against you?

GOMPERTZ: No, not at all. My experience at the Tate—they weren’t environments like that, they weren’t fearful environments where people were scared of making a mistake. I think part of that place’s success is their mental environment, where people would try things and try different things and some things would work and some things wouldn’t work. It definitely wasn’t a mark held against you. I suppose if you did it every single time you might not be asked your opinion on titles again.

BROWN: Were you surprised at how welcoming it was at the Tate?

GOMPERTZ: Yeah, I was actually. I thought I’d be there seven months, and I was there for seven years. I was surprised at how welcoming it was, and I’d apply that to the whole art world—it’s got this image of being standoffish and aloof or snobby or elitist and in my experience it’s never those, it’s just interested in ideas. It is, I think it’s safe to say, an academic world, which is sort of driven by ideas and exploring knowledge and exploring experience and quite highfalutin concepts. But actually, the people are great, really straightforward. There’s a trick, I suppose, of trying to get to the essence of what they’re trying to say in a way that can appeal to a wide group of people. It’s exactly why I wrote the book.

BROWN: Do you think that the art world has changed from not wanting to appear populist to becoming more embracing?

GOMPERTZ: Definitely. No question about it. There’s lots of regulating factors, from a desire to broaden the scope of influence—to get more people to come and look at art. But also from commercial factors, pushing art in places like Hong Kong, China, [and] India to build the market up so it can trade more successfully. I don’t think ever before in the whole of human history has so much art been made, bought, and sold. It’s a massive international business. So, I think there’s a lot of reasons why the art world as opened up and I think on the whole, it’s far better for it.

BROWN: What do you think the art world will be like in ten years?

GOMPERTZ: Different. I think it will have consolidated, I think it will slow down a little bit. I think it will be less white and Western, which it is still at the moment. There will be more female artists in the mix. I think we’ll see art forms explored through different media—the Internet, television, books, even. We’ll see art produced in forms and media that we haven’t seen yet.

BROWN: What do you look for in a piece of art?

GOMPERTZ: That’s a really good question. Personally, I look for a connection. An idea that touches me or reaches me or challenges me or provokes me. That means something to me. And I often look for beauty in form and structure, and for ideas. I think Rothko summed it up really well when he was talking about his own abstract art in his late period when he was painting lots of dark purple and blacks. Somebody said to him, “Why do you paint these great, big maudlin canvases?” And he said, “Because if there happens to be somebody who’s feeling a bit lonely and they come and stand in front of one of my works, they know they’re not alone.”

BROWN: Oh, I like that.

GOMPERTZ: It’s lovely. And that’s what I look for in art is exactly that connection.

BROWN: I know that you work for the BBC and you interview people yourself, and that recently you interviewed Sacha Baron-Cohen. How was that?

GOMPERTZ: It was good fun. It was interesting because he rarely does an interview out of character. I was surprised by how nervous he was. He really wasn’t comfortable being interviewed at all as Sacha Baron-Cohen. But once he got into his stride I found him very open and honest, actually, and funny, none of which is surprising. But I thought throughout the whole process that I was being set-up. I thought that it was a spoof because he never does these interviews. I was expecting something to happen.

BROWN: Well, maybe it still will.

GOMPERTZ: Don’t say that.

BROWN: Who would you most like to interview if you could interview anyone?

GOMPERTZ: David Bowie. I grew up listening to his music and I thought he had such a great effect on my age group. And he’s an interesting person. Also, Jasper Johns. I’d love to interview Jasper Johns.

BROWN: What would your first question be?

GOMPERTZ: Why the flag? [laughs]

BROWN: If someone—a child or a friend—came to you and said they wanted to be an artist, what advice would you give them?

GOMPERTZ: Be an artist. [laughs] Don’t say it, do it.

WHAT ARE YOU LOOKING AT? COMES OUT THIS FRIDAY, OCTOBER 25, VIA DUTTON AND IS AVAILABLE VIA AMAZON.